What A Book Means

I’ve spent nearly all the hours since March in my apartment. So my attention in these last months has focused on, flitted by, or ignored my books—shelves and shelves of books—more often than in any other period of my life. Yet I’ve read little. I can blame distraction, fatigue, despondency—and I do. But the presence of my books, of so much paper and ink, is also for me a series of unanswered questions: What am I? What part of you do I serve? Do I serve anything at all?

Here is for me what a book has meant.

I’m five. The book is a cradle, but one held right in front of me. I can somehow be in it and outside of it. It’s a gift, a book—but a gift that doesn’t go away. A book is a place I can go anytime from anywhere. I’m not yet able to go there myself, or go alone, but I sense the possibility of this privacy. This possibility is scary, like a shadow of a bigger, stranger possibility that seems like the lives my parents live. An inexplicable life. A book is a path towards that life, but it’s also an escape from it because each book’s colors are so clearly more vivid, more real, than the life outside a book. I’m amazed that my parents don’t talk about this, this secret they open for me whenever we sit down to read.

I’m ten. I seek the secrets of books whenever I can. I’m convinced the worlds they contain are more real than the life of my bedroom, than the life of school. I suspect the books I run away into and the land of my back yard I run across are related in some deep way: that there is a shared wilderness in them, a wilderness which quietly and patiently rejects the status of the fence. I want desperately to make more of this wilderness. So I write. I write because writing and reading are both the act of bearing in my mind what must in all circumstances live. I know that the imagination is a realm which must be protected from the grays and metals and routines of the clothing racks, the grocery store, and homework. I know that what must live is being attacked by regular life, or what everyone else but regular readers call regular life. I hoard books, because of the perspicuity of my situation. And I hoard them because I love their shape, the grain of their pages, the smells they hide, the glint of their spines in every kind of light. I am a fugitive in the world because of the truth of books.

I’m fifteen. There are books, just a few, that scream the unsayable. This scream and its agony are a shelter. These books hide me. These books also make plain the fact that other people have worked so hard to reveal what’s hidden. That this is the role of a book: to reveal, to unearth, to dig up and tear open and point and stare. Reading and writing books is a way—the way, the only way—of being honest. I realize that not only must I continue to structure my life around books, but that books are escape tunnels leading away from the ordinary lies of living. I realize more vertiginously that I am responsible for building these tunnels. And that these tunnels must be beautiful—that books must be beautiful, as objects—because they must be habitable in case someone like me gets caught in them. Because, I suspect, we only ever get caught in them.

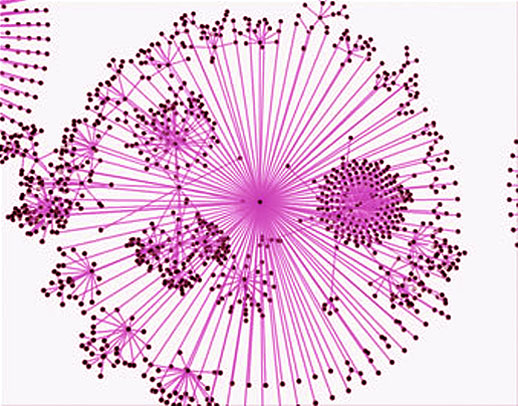

I’m twenty-one. The book is an event meant for other people. In making them, in editing and designing and soliciting them, I realize that books are events by which likeminded people are brought together. I view each book as an announcement, too: I have something important to say and I did my best to say it. Books can thus be judged by the social and financial context in which they were produced. Is this book’s announcement simply a commercial for its publisher, a little boon to the capital of that publishing company’s owners? If so, it can be scorned. Mocked. Or, ideally: ignored. The real shit, the real books announcing plain truths newly articulated, live among what our culture’s nervous gardeners call the weeds. The small press, the indie press: watchwords of those with good taste. Books are for and against: for the truth, for improvisation and innovation; against the dumb and redundant lies of the marketplace, against the formulaic and respectable. A book is an event for those rare good people to find and hold onto each other.

I’m twenty-six. A book is a piece of an infinite conversation, maddening in its scope and disunity, revelatory in its accidental harmonies which span thousands of years. To write or produce a book is to participate in this conversation. Yet the intensity and concomitance of this chaos and order makes walking through a bookstore or library exhausting, humiliating. A book, then, is a kind of sacrifice—because it is painful and costly to enter this conversation. The cost for a person who’s serious about books is that they can no longer speak with any grace during all those other conversations called “conversations” in day-to-day life: niceties, weather observations, constant nervous check-ins about the body and the mind and the state of the nation. Why? Because a great book is like a crystal whose form shapes great questions. In order to form these crystals, an author must permit themselves only the cold and arid air of solitude, distance, erudition, and honesty. Being open to this air requires a distance from one’s friends, one’s family. A book requires one’s blood.

I’m thirty-one. As I type this sentence, I’m looking at the rows of books I own. Despite making and spending money, I don’t like the sound of that: that these are my books. They’re not mine. They’re just temporarily living with me. And they do that: they live. They live because a book testifies to life. Not to the bland, back-of-the-cover-copy version of life, with its glib emphasis on the human and the joys and sorrows of social existence. A book testifies to the wider, stranger, more terrifying and fulfilling life we know when we are most inexplicable to ourselves. I’ve known this wider life when I’ve experienced any love whose existence I couldn’t fit into my vision of the order or disorder of things. Every gift points at this wider life; I’m sure of this. And I’m sure that each book is a gift.

Oil

The other day, one of my students asks me where oil comes from. I am helping him with an article about climate change and the oil industry that he was supposed to summarize for the previous week’s assignment. English is his third language and the one he struggles with the most, so we are sitting at his desk after dismissal going through his article line by line.

I’m surprised that he asks me that, where oil comes from, and then I’m ashamed at my own surprise. He has no reason to know the answer.

I could tell him that where I grew up, the drumbeats of the oil rigs were as familiar as the sound of my own heartbeat, or that my first school had an oil derrick next to the swing set, caged in with a barbed wire-topped fence and locked with heavy chains. READ MORE >

The Title

In so much art, I can smell the author’s desire for me to be more interested in how they and/or their characters interpret and inhabit boredom than actually doing something. Simple action. Anybody involved doing anything. I’m thinking here of The Stranger, The Third Reich by Roberto Bolaño, The Immoralist. The strung along. The boredom of relative luxury. How this seems to at least temporarily obliterate any internal gyre of philosophy or gut thought that would lead to decisions being made and bodies being moved, followed then by trailing thought, fallen out words. Is there a novel out there concerned mostly with people moving and acting with little thought, but in which plot in its traditional patterns of building (attention, suspense, terror) does not build its usual cores but delves or unearths something deeper in its time: meaninglessness? Beckett, I guess, right? Of Molloy. And not yet just a list of actions but a trail of subsumed desire, of wiped want, or cleaned out intuition. Belief born without a tail. Who’s out there? And how are they speaking? And in that smell, be it a pleasant suprasense or the shit of deadening culture, you can either yes to it or no and walk away, close the book. Off the screen. Say hi to a realm of light and seeming chaos that somehow provides you wind.

But meaninglessness is tricky. Just as the word impossible is framed by a language that both codes it and decodes it simultaneously (it’s a combustive word; no wonder artists take it as such an engine), meaninglessness doesn’t truly touch through the black skein of a void, the void, void. We know it just gestures. (from Mark Leidner: poetry like the Midas of meaning; everything you reach for is dissolved in the spectacle of the gesture) So we’re left with a hologram of a projection of deeper sense or finality: we’re left just out of reach of the point of cataclysm, or at least where the earth can break through enough to swallow its container. It’s not geometrical at all, nor is it a sphere without a skin: in a way, culture in its progression, bacterial (maybe moreso than a viral way), keeps as its form the method by which we can get as close to a system of thought’s event horizon. A hollow zone where the force holding you in place is milliseconds away from its pull toward another place: lesser star, complete off.

I dreamed earlier today about writing I am paralyzed. In the near immediate wake of death. And how, seeming to me then in the open dream, that must necessarily precede a statement of numerical precision: how many times the page itself I had typed or tapped onto white had been deleted. And reformed, necessarily. All I’m thinking about now is how the Dionysian and the Apollonian were easy outs. It seems to me both of those frames of vision have a third hand somewhere: just out of frame, the marble grates against its mate. Touch.

How I Got Here

Becoming is weird. I have theories: how I got here, what lead me, what pushed me out of one interest and into the next. I don’t get too high on rethinking and visiting my quick past, which, if I had to guess, is a big reason why I’m happy most of the time. I’m not that interested in my past, not as reportage, not as history. But consider this an essay in its primordial meaning: an attempt at a history. That black space with the electricity below it right above, that’s it.

When I was little I frequently made stuff. Stories, goofs. I was really into drawing, and applied to one of those mail-order Drawing Schools (to prove my might I had to draw a weird turtle boy’s face and include some mom money). My mom and dad, ever the best ever, obliged and encouraged me. Always. Throughout this entire post, remember that thread of encouragement. I’ve never lacked it from those close to me. If I’m not lucky I’m not anything else. Art class in school fed me, kept me wanting. I remember getting into a shoving match in second grade — was the kid’s name Kurt? — over who had drawn the better Star Wars TIE fighter. I fake hyperventilated when the teacher came to break it up, feigning something bodily urgent, and was made to stand against a wall and breathe slow. Kurt got punished, maybe spanked. I don’t know. It was Texas.

“Nothing ever happens.”

This is the first installment of what I might call Litblogging Wis Frvr or something like that. Sort of an anthology-in-progress.

The Book: A Spiritual Instrument

by Stéphane Mallarmé

I am the author of a statement to which there have been varying reactions, including praise and blame, and which I shall make again in the present article. Briefly, it is this: all earthly existence must ultimately be contained in a book. READ MORE >

“Whose arm is this?” She said, “That’s my mother’s arm.” Again, typical, right? And I said, “Well, if that’s your mother’s arm, where’s your mother?” And she looks around, completely perplexed, and she said, “Well, she’s hiding under the table.”

– Errol Morris on anosognosia and much much more, in five parts. Starts here.

Against Dualism: Yes That Is A Joke: A Response.

I. Fontana on Publicity

[This is a comment–regarding some recent posts here–that I. Fontana posted and also sent out to me & Ken, and we thought it was worth presenting on the main page for those who missed it. I. Fontana knows whereof he speaks, and he’s one of my favorite “new” writers out there. Love his short stories, which I’ve linked on HTMLGIANT before, and I know he’s got some other stuff in the works that I’m very, very excited to see published. –N.A.

Nick says it: I. Fontana says it. Presented with no further ado: –K.B.]

Superagent Nat Sobel said in an interview last summer that he chooses at most one in 500 unsolicited manuscripts to represent in a given year. Grove/Atlantic, HarperCollins etcetera — all the major New York publishing houses, in other words — explicitly announce that they will not read any manuscript which does not come from an established agent.

In the early 19th century, literature (and in particular the novel) evolved into a popular art form generally serialized each week in newspapers, which meant that in order to keep the particular novel being read, there had to be narrative pull, even cliffhangers — in general, plot. But this meant that the socalled “unwashed masses” now were exposed to such writing, so that writers no longer had to hang around court or otherwise suck up to aristocrats, publishing their books by subscriptions to the wealthy (which constriction obviously required that the wealthy find such books pleasing). Democracy means including the lowest common denominator as well as the connoisseur.