How I wrote my latest novel, part 1

I’ve wanted for a while now to try writing a story “live” here, posting my work as I went from initial idea to finished piece. I might still do that, but for now, here’s a related series of posts. I spent the past forty days writing a new novel (“Lisa & Charlie & Mark & Suzi & Monica & Tyrell,” though my working title was “The Porn Novel”), and want to share with you how I did that. My hope is this will prove less an exercise in vanity and more something instructive—like, you might want to do the exact opposite of me.

Let me state up front that I don’t think there’s any one way to write novels, or fiction, and I don’t approach all of my projects in the same way. And what works for me may not work for you. But I have developed some basic procedures that I find useful and that you might enjoy trying. Also, this time around, I encountered some formal problems that should make for good discussion.

I write pretty quickly, but forty days is the fastest I’ve written a novel. (This is the third one I’ve really completed.) My first novel, Giant Slugs, took nearly a decade from start to finish, during which time I wrote three completely different versions of the book. That experience was, on the whole, difficult and often mystifying. Only in the final two years, when I wrote the final version of the novel, did I feel as though I understood what I was doing, and even then I felt crazily out of control most of the time. I had by then a Master’s in Creative Writing, but never received much instruction in novels, so I had to figure out a great deal on my own. (Perhaps that’s inevitable?)

I wrote my second novel, “The New Boyfriend” (still unpublished) as an anti-Giant Slugs: whereas GS is a mock-epic with dozens of characters and locations, covering several years, “TNBF” is a single scene featuring four characters, set in a single location on a Sunday afternoon/evening. That project took me seventy-five days total, which taught me that time is a resource, and some projects take less of it than others. I’m sure I’ll return to more time-intensive projects later, but for now, I’m having fun sprinting.

Recently I’ve wanted to try writing a novel in one month, and when I dreamed up this new project, it seemed a good candidate for that. (And, no, I’ve never done NaNoWriMo, though I have done the 3-Day Novel Contest about six times. I learned a lot from doing the 3-Day, but never produced what I’d consider a finished novel.)

The difference between a concept & a constraint, part 1: What is a concept?

Sol LeWitt: “Wall Drawing #1111: A Circle with Broken Bands of Color” (2003, detail). Photo by Jason Stec.

[Update: Part 2 is here.]

I wrote about this to some extent here, but I wanted to expound on the issue in what I hope is a more coherent form. Because I frequently see concepts confused with constraints, and the Oulipo lumped in with conceptual writing. For instance, this entry at Poets.org, “A Brief Guide to Conceptual Poetry,” states:

One direct predecessor of contemporary conceptual writing is Oulipo (l’Ouvroir de Littérature Potentielle), a writers’ group interested in experimenting with different forms of literary constraint, represented by writers like Italo Calvino, Georges Perec, and Raymound Queneau. One example of an Oulipean constraint is the N + 7 procedure, in which each word in an original text is replaced with the word which appears seven entries below it in a dictionary. Other key influences cited include John Cage’s and Jackson Mac Low’s chance operations, as well as the Brazilian concrete poetry movement.

I would argue that the Oulipo, historically speaking, are not conceptual writers/artists—although it’s easy to see how that confusion has come about, because the Oulipians have proposed some conceptual techniques, such as N+7 (which I’d argue is not a constraint). (Also, it’s each noun that gets replaced, not each word.)

What, then, distinguishes concepts from constraints? And why does that distinction matter? In this series of posts, I’ll try answering those questions, starting with what we mean when we call art conceptual.

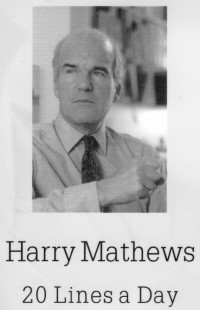

25 Points: 20 Lines a Day

20 Lines a Day

20 Lines a Day

by Harry Mathews

Dalkey Archive Press, 1988

134 pages / $10.95 buy from Dalkey

1. In the fifth floor of the library, I picked the book up, read what the premise was, and thought resentfully, “What a bunch of bullshit, this looks boring, look how anything gets published.” I didn’t know who Harry Mathews was yet. Years ago.

2. “You never have earned the right to sit at the table and let someone else clear away the dishes. No accumulation of knowledge can guarantee that you aren’t a fool. The roast is over-cooked. You slice bread for the seven-hundredth time and cut off the tip of your left forefinger. You touch her as coarsely as any boor, being now the boor. You meet an old friend, you have forgotten his name, you cannot look him in the face: not looking him in the face, you wound him and you start lying to him and to yourself. Go off and sulk and complain and explain why it happened. It won’t help. Instead, be an actor, or an athlete, on stage, on the field, giving–as you once eagerly proposed to yourself–everything to the perishable act.”

3. “I have nothing to write in particular, I’m writing these lines because of my rule that I must write them.”

4. Some writers set quotas, others set routines, some set both, and some (the scriptomanic ones for whom procrastination is not a threat) set neither. A page a day (Paul Theroux); 50,000 words in a month (NaNoWriMo); two hours every morning (W.S. Maugham); 20 minute blocks (Cory Doctorow); at least a sentence a day (W.G. Sebald); pre-dawn (Paul Valéry, Jacques Roubaud); etc.

5. “Whatever I write tells my story without my knowing it.”

6. “Let no thought pass incognito, and keep your notebook as strictly as the authorities keep their register of aliens.” (Walter Benjamin, “One Way Street,” Reflections)

7. “Sometimes the ultimate message is in fact received. It reads, more or less: ‘Your ligament issues from a spa that is given various narcissisms at various time-tables: lozenge, credulity, goggles. And not only your ligament (and that of others): the prodigy that generates mayday has the same orthography. You and the upkeep are one. Give up sugarbowls.’ At such moments you realize, and you remember, that such messages have never been lacking, and that they are all the same, and that the problem (if that is the word) doesn’t involve receiving but deciphering what is received again and again, day after day, minute after minute.”

8. There’s an implicit link between 20 Lines a Day and the next novel Mathews would publish, The Journalist (1994). One sees how the method Mathews followed for 20 Lines is adopted as a fictional premise and device for The Journalist.

9. “Anxiety about writing feels like: I am poor in words, ideas, and feelings, and when I sit down to write, this poverty will be revealed.”

10. “The table is a beautiful thing. The writing board is supported on a base consisting of two tubular legs shaped like narrow inverted U’s, with a tubular foot running across the mouth of each U, projecting about thirty centimeters beyond it on either side. The legs are connected to the board by an adjustable parallelogram made of bone-shaped pieces of flat metal. The knobs of the bones are pierced with pivotal studs that hold the sides of the parallelogram together. Two strong springs, to hold the angles in place, maintain pressure against two other springs fixed just below the board. A single lever controls this disposition and locks the board in place. Changing the angles of the parallelogram permits one to alter both the height and angle of the board in one movement. Board, parallelogram, legs and feet are white; springs, studs, and lever handle are black.” READ MORE >

October 25th, 2012 / 9:09 am

At the Quarterly Conversation, “Ed Park, Laird Hunt, Dan Visel, Jeremy Davies, A D Jameson, John Beer, and Daniel Levin Becker each discuss one of [Harry] Mathews’s books… from The Conversions (a novel worthy of William Gaddis, as Dan Visel puts it) to Cigarettes (Mathews’ most conventional, and only truly Oulipian, novel, says Jeremy Davies) to Mathews’ poetry (discussed by award-winning poet John Beer) and his unclassifiable Selected Declarations of Dependence (discussed by his fellow Oulipian Daniel Levin Becker).”

A Pan-English Dictionary (for readers of Harry Mathews’s The Sinking of the Odradek Stadium)

And while on the subject of reposting literary resources: here’s a Pan-English dictionary I made for the benefit of anyone reading Harry Mathews‘s early masterpiece, the epistolary novel The Sinking of the Odradek Stadium.

And while on the subject of reposting literary resources: here’s a Pan-English dictionary I made for the benefit of anyone reading Harry Mathews‘s early masterpiece, the epistolary novel The Sinking of the Odradek Stadium.

Odradek presents the correspondence of newlyweds and amateur sleuths Zachary McCaltex and Twang Panattapam. Separated by the Atlantic, they exchange letters in which they “try to trace the whereabouts of a treasure supposedly lost off the coast of Florida in the sixteenth century, while navigating a relationship separated by an ocean as well as their different cultures.”

Twang, who hails “from the Southeast-Asian country of Pan-Nam,” peppers her letters with snatches of her native language, “Pan.” Fortunately for her husband and the reader, she also translates it on the spot. I’ve collected all of the Pan and its English equivalents and presented them below.

20 Lines from 20 Lines a Day by Harry Mathews

In 1983-1984, while writing Cigarettes, Harry Mathews followed Stendhal’s dictum of writing “twenty lines a day, genius or not.” In 1988, Dalkey Archive published the notebook of all of Mathew’s daily 20 lines. Lots is genius. Here are 20 bits (though I will note that the real pleasure is in the accrual of the bits in daily sections and in the whole project, so if you like the bits then just think!):

In 1983-1984, while writing Cigarettes, Harry Mathews followed Stendhal’s dictum of writing “twenty lines a day, genius or not.” In 1988, Dalkey Archive published the notebook of all of Mathew’s daily 20 lines. Lots is genius. Here are 20 bits (though I will note that the real pleasure is in the accrual of the bits in daily sections and in the whole project, so if you like the bits then just think!):

No matter how much one loves sunshine, its assault here on the eyes and skin makes shade delectable. One knows one’s tan will have more fuel than it can use.

…even if the air was cluttered with social smells and substances.

Or should one aim at portraying objects that are perpetually in flux or, better, that are transformed by our very description of them, like this page?

…but even if the basis of simile is continuity, to compare wobbly daffodils to invisibly moving stars is like comparing white bunny tails to snowy mountain peaks. So let’s do that.

…how to manage disagreeable emotions by scheduling them…

‘Nothing will ever be the same,’ except oneself, and who wants to rely on that pathetic little monster?

Do I now run errands to make the outdoors safe? Why does buying things, especially ones that are relatively expensive, calm me so extraordinarily?

But watch out: ‘fragmented, exciting’ mustn’t become an excuse for getting less done.

Every morning–early every morning–I’ll set aside ten minutes and concentrate exclusively on feeling anxious about sitting down to write. The most rudimentary sense of absurdity should get me going by minute number three.