Name less than five books published in the last decade that you’d sacrifice all the others for.

Help APRIL out with Reverse Fan Mail!

One trick I do to coax up sleep is I let my mind do whatever. Like I figure that’s what it does when I sleep anyway, so why not let it out early? A porch-like transition into the backyard of dreaming. Sometimes what it does is a picture of someone carrying a pie tin to the river. Kneeling in the shallows. Other times—last night specifically—it did a succession of closer and closer zooms onto a very elaborate game of bowling. Specifically the windup was elaborate, and the ball was small. Also the pins seemed irrelevant. In 2014, I encourage you to let your mind do whatever you want. I mean whatever it wants. Shit. Not off to a good start.

One trick I do to coax up sleep is I let my mind do whatever. Like I figure that’s what it does when I sleep anyway, so why not let it out early? A porch-like transition into the backyard of dreaming. Sometimes what it does is a picture of someone carrying a pie tin to the river. Kneeling in the shallows. Other times—last night specifically—it did a succession of closer and closer zooms onto a very elaborate game of bowling. Specifically the windup was elaborate, and the ball was small. Also the pins seemed irrelevant. In 2014, I encourage you to let your mind do whatever you want. I mean whatever it wants. Shit. Not off to a good start.

So I will reverse course entirely and find something else to talk about: Reverse Fan Mail from APRIL. APRIL of course is a crafty bunch of Seattle folk who are dancing the good dance for Authors, Publishers, and Readers of Independent Literature. I’m pretty sure that’s what APRIL means without even looking it up. They’re that good! They do stuff like host book clubs, festivals, expos, reading bar crawls, and generally make Seattle seem fun and utopian to those of us in New England surrounded by leftover-mashed-potato-looking snow.

To do all that fun stuff, they need a little help. Yes, it’s that kind of post! But they give you stuff if you send them skrill. They have people write poems for you. They have people draw things for you. That’s Reverse Fan Mail. Hell, I’ll write you a poem. It says so right on the page. So will Stacey Levine, Ed Skoog, Joshua Beckman, Matthew Rohrer, Mark Leidner, Ryan Boudinot, Rebecca Bridge, Jac Jemc, Wendy Xu, Jane Wong, Rich Smith, Ted Powers, Peter Mountford, Drew Swenhaugen, Amber Nelson, Megan Kaminski, Richard Chiem, Matthew Simmons, and Doug Nufer.

What I’m saying is you should click here and give some $$$ and get lazy-ass Leidner to write you a poem about dreaming and bowling. Originally this whole post was going to be about how one time Leidner texted me “patient B43 tested positive for PVTA,” which is a Western Massachusetts themed joke that I decided would alienate people and lead to less money for APRIL. So I thought: what’s less alienating than Western Massachusetts? Dreams. Futures. Elaboration. Click here to donate to APRIL, get a Reverse Fan Mail, it’s for a good cause, they’ve got a great 2014 Festival planned. Help ’em out. Get a poem. Get a drawing. Give your slippy mind a new year present.

What I’m saying is you should click here and give some $$$ and get lazy-ass Leidner to write you a poem about dreaming and bowling. Originally this whole post was going to be about how one time Leidner texted me “patient B43 tested positive for PVTA,” which is a Western Massachusetts themed joke that I decided would alienate people and lead to less money for APRIL. So I thought: what’s less alienating than Western Massachusetts? Dreams. Futures. Elaboration. Click here to donate to APRIL, get a Reverse Fan Mail, it’s for a good cause, they’ve got a great 2014 Festival planned. Help ’em out. Get a poem. Get a drawing. Give your slippy mind a new year present.

Black Candies: See Through: A Journal of Literary Horror

Black Candies: See Through: A Journal of Literary Horror

Black Candies: See Through: A Journal of Literary Horror

Edited by Ryan Bradford and Jay Wertzler

SSWA Press, 2013

141 pages / $13 Buy from So Say We All

The 1978 John Carpenter film Halloween opens with the camera serving as the viewpoint of a child. The audience watches the boy spy on his sister from an outside window, then put on a clown mask, pick up a meat cleaver, and climb the stairs. We, as the audience, then see from (who we learn later to be) a young Michael Meyers’s perspective as he surveys his topless sister and then proceeds to stab her.

There is little to no blood in this iconic murder scene. In fact, the only real blood is a relatively small dab on the knife as Myers stands in his clown costume on the front lawn awaiting his parents in the following shot. And yet, this is one of the tensest scenes in the movie as it blends a creepy synthesized score, eerie lighting, and that mask over the camera effect to create an unnerving sequence. What’s particularly intriguing about Halloween is that this scene of the film has so little outright gore more because of a shoe string budget and restrictions with child actors than for any consideration of taste or propriety.

Those who are familiar with the rest of the Halloween franchise know that only Carpenter’s original pulls off the lack of blood effectively. In fact the rest of the series, especially the Rob Zombie reboot of 2007, amps up the blood by the gallon—mainly because they lack Carpenter’s subtle, directorial hand.

There is a proliferation of gore in horror film franchises. Compare, for example, the first Texas Chainsaw Massacre, which does begin the film with disinterred corpses and uses a shot of the actress Marilyn Burns really being cut by Gunnar Hansen, but never explicitly shows anything much worse to later iterations. Rather, in the 1974 film, Tobe Hooper only suggests girls being impaled by meat hooks with close up shots of dangling feet and a squishing sound effect or being chopped up with the eponymous piece of hardware. However, later iterations of the film, especially the 2013 3D extravaganza that features the same hook scene with the hook pointing out the other side of hapless Kenny’s gut followed by a slow grinding in half via chainsaw thanks to Leatherface added, add far more gore, but at the cost of the plot and ambience of the films.

Wes Craven’s 1977 The Hills Have Eyes is one of my favorite of the late 70s New Horror films because it depicts a stranded family beset upon by inbred hill people. There is little to no suggestion that these folk eat baby flesh for any other reason than because they are crazy, and the final scene in which the father takes his revenge on the clan leader with a knife repeatedly to his chest is par excellence, but this was all undone with the 2006 remake which replaced Michael Berryman with giant radioactive horrors with oozing tumescence.

In many ways, horror fiction is subject to these same issues. Zombie novels and backwoods killers are all depicted with such heavy-handedness. Black Candies, on the other hand, is a journal of literary horror which strives to feature horror fiction that features a little more panache. It’s a relief to see a journal trying to push for quality horror writing, especially writing from women (who are woefully underrepresented in the genre at large). As a result of these efforts, the very best selections in the most recent issue (with all selections reacting to the theme “See Through” ) operate under the same principle as the best horror films of the seventies—that less is more.

In “I’m Pogo,” Lindsay Hunter uses the reader’s previous knowledge of John Wayne Gacy and the touchstones of pedophile clowns spawned by his crimes to build dread. There’s no outright violence in her story, rather repeated phrases like “tourniquet, tourniquet …” and sentences like “You know, tremblefleshed wifebound line cooks jailed for sodomy learn quick how not to be jailed the next time. The word is pederast.” In many ways, this is more terrifying for her readers than a direct description of pedophiliac rape.

Jac Jemc’s story “Angles” also builds upon haunted house tropes, but uses the affectless phrasing, “maybe it was the neighbor children who rang the doorbell that night or maybe it was just some faulty wiring or maybe the faint ring we heard was something else entirely: a thing we would only recognize later,” which increases in intensity as the story progresses as the narrator later says, “maybe I find a body and it’s hard as diamonds or maybe I find the body and it’s just a pile of soft bones and teeth or maybe it’s a body whose nails have screamed themselves free of absent fingers. What will a rat eat first?” The story becomes scary more because of the narrator’s refusal to acknowledge the strange goings on rather than because of actual ghosts or guts.

In other stories Aaron Burch uses the familiar frustrations of hotel life to depict a man driven too far by a dog, and Ken Bauman’s “Lathe” meditates on the real-life horror that is surviving the death of loved ones to make something chilling and beautiful.

Not all mainstream horror is heavy-handed. Ti West’s contribution to the film V/H/S is one of my favorite recent horror movies and Joe Hill and Benjamin Percy are frequently producing quality horror novels and short fiction, but the best of the best of the genre remains see through to the general public. Maybe this is because, on a base level, audiences don’t actually want to be scared. They just need something to watch on a date which encourages squeezing hands and not much further thought. Mainstream horror is populated by zombies, maniacs, and sharktopi which require little headspace—they’re spooky, but they don’t affect people in the real world, whereas literary horror inhabits the subtle, everyday terror that pervades people’s lives. After all, the scariest horror is that which we cannot see. In “This is a Ghost Story,” a ghost asks the narrator of Juliet Escoria’s story “What are you so afraid of?” She responds “Everything, … it’s everything in this world that scares me…”

***

Quincy Rhoads teaches English composition at Austin Peay State University. He lives in Clarksville, TN with his wife and their son. His writing has been featured online in Everyday Genius, The Fiddleback, and Unicorn Knife Fight.

December 30th, 2013 / 11:00 am

Use of Weapons by Iain M. Banks

Use of Weapons (Culture Series)

Use of Weapons (Culture Series)

by Iain M. Banks

Orbit; Reprint edition, July 2008

512 pages / $15.99 Buy from Amazon

The Culture series by Iain M. Banks just keeps on getting better and in Use of Weapons, the narrative takes on added complexity in a two-pronged narrative that intertwines the tale of a hunter, Zakalwe, who has left the Culture and a woman, Sma, who still works for them. I’d go so far as to say this is one of the most experimental works by Banks, or for that matter, any science fiction writer, particularly in light of the ending. Because of its added intricacy, I (PTL) invited Joseph Michael Owens (JMO) and Kyle Muntz (KM) to collaboratively review the book and share/debate/spur our thoughts in a “cultural” exchange.

Peter Tieryas Liu: What was your take on Zakalwe and Sma in the pantheon of Culture characters?

Joseph Michael Owens: To be honest, Cheradine Zakalwe and Diziet Sma are probably two of my very favorite Culture characters overall, and I’m currently reading the last book in the series. The chemistry between them is truly fantastic. It’s hard to explain without giving away major spoilers, but you’ve got a really fantastic setup where you can see there is a great detail of history between them and it’s 100% believable. You can feel that they know each other incredibly well and, in some situations, they’re really the only ones that can handle each other.

Banks is also good with layering characters’ roles, and you get the feeling that both Zakalwe and Sma have done and seen a lot that doesn’t necessarily have to do with their current occupations, which I love. I think it adds an extra human element to the characters, these two specifically, because we’re shown that they exist — and have existed — outside of this single narrative. And since they feel like people and thus read like people.

The ending is . . . it’s just wow. . . .

Kyle Muntz: I’m not sure I can add too much to Joe’s comments (since I think that’s totally on-base and right), but in retrospect, I’d say Diziet Sma in particular has really stuck with me. The Culture series has a lot of strong female characters, but Sma is definitely one of the most interesting and best realized. For me, one thing the experimental elements of the novel call attention to (by telling Zakalwe’s story forwards and backwards at the same time) is how broad life is; and how separate different episodes in it can be. Especially when the chronology is destabilized. The novel gives glimpses of the same people, years apart–and each time they seem different, sometimes almost unrecognizable. And that’s life.

Use of Weapons is the last Culture novel to focus on a small cast of characters. After this, it becomes a sequence of vaguely Pynchonian ensemble pieces, and while I love the broader scope that brings to the series, it makes me appreciate the more intimate characterizations of the earlier novels, especially this and Player of Games. Characterization wise I think Banks is in top form here. In general, every Culture novel is unique, but formally none of them stand apart as strongly as Use of Weapons.

PTL: One of the most interesting chapters is when Banks’ describes Zakalwe’s first time aboard a Culture ship, Size Isn’t Everything. It’s our first real exposure from the eyes of a newcomer to how different the Culture is from everything we know, particularly with a post-scarcity economy in which anyone can do what they want.

One of the dialogues I remember is a waiter who talks about what’s important in life and why he enjoys wiping tables when he can do anything he wants: “I could try composing wonderful musical works or day-longer entertainment epics, but what would that do? Give people pleasure? My wiping this table gives me pleasure. And people come to a clean table, which gives them pleasure. And anyways, people die; stars die; universes die. What is any achievement, however great it was, once time itself is dead?” What do you guys think about the Culture? Things you like and dislike?

JMO: I remember Banks saying once that he modeled the Culture off of his ideal utopia, which is kind of cool because that’s an example of the power of writing and creativity: you can literally create your own world, and then go play in it! There’s really nothing I dislike about the Culture; I’m like the ultimate Culture fanboy. The way I’ve read it since book 1 (Consider Phlebas) is that a pan-human race created AIs that were able to perpetuate and evolve themselves into the Minds we know and love in current Culture novels. The AIs basically take care of all the mundane activities for humans so that humans can dedicate themselves to whatever they want: art, recreation, education, various experiences in general. Disease has been eradicated in the biological citizens, and people can augment themselves any number of ways they desire for utility or for fun. This sounds totally like a place I’d want to live!

KM: There’s a certain amount of tension within the novels about the Culture, mostly questioning how such a powerful, secular, completely free, post-violence, post-scarcity society (controlled entirely by machines) should interact with violent, oppressive, warfaring societies who rule themselves and do a terrible job of it. But I think the Culture is objectively pretty perfect.

I read the series over a year ago now, but it was the setting that kept me coming back: the Culture, endless, unchanging, as a place to live and way of life to be explored. Genre fiction tends to treat society as something to be moved: societies fight war, are saved from corruption, whatever. Which I’ve always thought was boring, and pushes me away from series like Song of Ice and Fire. Instead, the Culture is basically incorruptible and one of the most intellectually sound utopias in fiction. (Another good example is Triton by Samuel Delany.) There are elements of the setting I still think about pretty regularly, and in retrospect even echo through a novel I wrote called The Holy Ghost, which was about a utopian-ish society that did have to deal with scarcity.

Another main tension is always going to be that the Culture isn’t run by people — it’s run by machines infinitely smarter and, yes, more humane than we’ve ever been. This isn’t something I’d want to dive too deeply into, other than to say: I don’t really see the problem.

PTL: The contrast between the Federation (e.g.) in Star Trek and the Culture is fascinating in that while both are postscarity, the latter embraces human nature to an extreme while the Federation espouses a future in which human nature is transcended. Sma is casual about her sexual liaisons with crew members and all hints of traditional morality are banished, whereas in the Federation, conservative values are still very prevalent. But the biggest difference is that the Minds run the Culture whereas the Federation has a council that is susceptible to corruption. So in that sense, the Culture could not exist if it weren’t for the Minds and Artificial Brains that are in control. Beychae, the target of Zakalwe’s chase, poses an interesting thought: “The Culture believes profoundly in machine sentience, so it thinks everyone ought to, but I think it also believes every civilization should be run by its machines.” Zakalwe replies: “I have no idea whether they’re the good guys or not… They certainly seem to be, but then who knows that seeming is being? I have never seen them be cruel, even when they might have claimed they have an excuse to do so. It can make them seem cold, sometimes. But there are folks that’ll tell you it’s the bad gods that always have the most beautiful faces and the softest voices.”

In some ways, these “Artificial” Minds are the future gods, albeit quirky and eclectic ones. Do you think there’s an assumption by Banks that humans can’t achieve this totally peaceful society by their own means and need someone else in control? For all practical matters, if there were a master species of aliens that were also benevolent, they could easily take the place of the Minds in the fiction (though that probably would have been harder to swallow for human readers who would equate it to human slavery).

JMO: I like the Minds-as-future-gods idea because to us, they would be, especially given that they (i.e. the Culture) are a level 8 civilization. However, there are also level 9 and 10 civs out there (10 being those civs that have Sublimed, if I recall), who are ostensibly gods even to the Culture and other level 7-8 civs. This is something you are even given an example of in the final Culture novel, The Hydrogen Sonata, when one Mind talks to another that has actually returned to “the Real” from the Sublime (something that is almost unheard of).

Also, I got this from a wiki: “Also significant within the Culture novel cycle is that the book shows a number of Minds acting in a decidedly non-benevolent way, somewhat qualifying the godlike non-corruptibility and benevolence they are ascribed in other Culture novels. Banks himself has described the actions of some of the Minds in the novel as akin to “barbarian kings presented with the promise of gold in the hills”.”

I think the idea is that, once Sublimed, you are fully actualized within the greater universe. One of the feelings you get, however, is that Subliming is something civilizations also do when they — for lack of a better term — get bored, and decide simply to “retire.”

To go with your main question, I think as long as there is a sense of “us” and “them,” or more specifically, “the other” — and as long as there are resources that are not available to everyone — it will be incredibly hard for humans to achieve such a totally peaceful society by their own means. Humans are inherently opportunistic, even when they have the best intentions. As long as someone else has something you want, you’ll likely experience some level of envy. Oftentimes the sense of envy will be manageable, but what happens when it’s not, i.e. in situations where what you want involves feeding starving people? Of course that’s a base need versus simple want, but when resources become scarce, the line gets blurry.

December 30th, 2013 / 11:00 am

Some books I read this yr.

The other day I was eating from a large tin of popcorn. Someone asked which is your favorite. Thru chews I said I like them all / for different reasons. That’s how I feel about these books.

The Parable of You by Tony Wolk

The Parable of You

The Parable of You

by Tony Wolk

Propeller Books, November 2013

90 pages / $12 Buy from Propeller Books or Amazon

The 17 stories in the 90-page The Parable of You feel like vignettes in the true sense of the word.

“The Nameless Ones”: A purposefully obscure Cinderella figure doesn’t wake up one day. The narrator arrives to wake her from her slumber. The story ends.

“The Shipwrecked Sailor”: The story’s namesake finds a house with a small door on an otherwise abandoned island. He enters, and finds that the contents of the room he has stepped into shift and disappear. The story ends.

“The Jogger”: Abraham Lincoln sets out on a run. He reflects on “The first time ever that he had traded Vulcan’s boots for the moccasins of Mercury and took to the countryside.” The story ends

At first I was a little hard on these stories. I used my newly acquired workshop language to diagnose them: “Not fully realized,” I penned in my notebook. “Linguistically cumbersome.” But the stories toward the end of the collection began to win me over. In “The Minkfarm,” for example, a young narrator visits a fur-coat farm with his reticent father. It is a longer story, relative to the rest of Parable, and by the end the boy watches a horse tied to a series of posts and shot.

I saw the horse shudder and go limp, its head slack. The four ropes kept it from falling. Then, with the shot still reverberating in the nearby trees, I realize that father’s hand was on my shoulder, gripping me tightly, holding me close.

This is good stuff, and fully realized indeed. It is just approached from the side, through the point of view of a man who now has his own children, thinking about his own childhood. A different writer might just tell the story. Tony Wolk doesn’t. He weaves a frame for the nostalgia, a specific man on a specific night—“the half-moon is waxing”—to recall the substance of the story. It is only a paragraph on either side of the piece that provides this frame. Still, such insertions are strange to see. It is not out of necessity that Wolk has written them. It is out of something else.

What I’ve come to understand is that, instead of being not-good, The Parable of You reads like literature in translation. The feeling I had in reading Wolk is similar to how I felt when I read Cortázar’s Hopscotch for the first time, and his Historias de cronopios y famas (the latter of which I made the mistake of trying to read in Spanish): as if I had encountered something very interesting and probably great, but didn’t quite have the tools or cultural logic to appreciate it for what it was.

There even seem to be different conventions here in the choice of subjects. Like Wolk’s three novels in the last ten years about a time-traveling Abraham Lincoln, two stories in the collection take on Abe as their subject. It’s almost like some weird American fetishism, except for the fact that it’s undertaken by an American. It seems wildly uncool to me to write prospectively indie fiction about the namesake of one of Bill O’Reilly’s most recent books, but I can’t imagine that Wolk cares much at all.

Even the title of his collection seems bizarrely straightforward and genuine. This is not what we expect from a young, indie press in Portland. But the story that gives The Parable of You its name is an awesome one, based on the problem of the drunken sailors. It ends with the spatial equivalent of Shakespeare’s typewriting monkey: even if you’re set out, blindfolded, to wonder the universe forever, you will eventually make your way back to the lightpost where you began. The story, and the book, end:

Your hand traces the familiar scoring, the X, the series of grooves, your name. You remove the blindfold. You are on the corner again. The universe is finite. In time, you will always come home. Always.

December 27th, 2013 / 12:00 pm

Deaver’s Great Chain of Being

This year, I went on a small, self-financed West Coast book tour. As a tool to market my book, it was not terribly successful. Ah, well.

As a vacation, though, it was wildly successful. There were some things on the West Coast that I had wanted to see, and I got to see them. I saw The Winchester Mystery House. I saw The Esalen Institute. I saw The Madonna Inn. I saw molting seals. I saw The Watts Towers. I saw The Museum of Jurassic Technology. And, best of all, I finally got a chance to see and use Deaver’s Great Chain of Being. READ MORE >

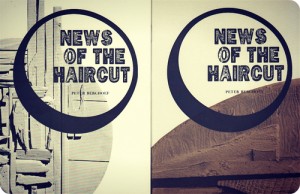

News Of The Haircut by Peter Bergoef

News Of The Haircut

News Of The Haircut

by Peter Bergoef

Greying Ghost Press, Originally published 2007 / Republished 2013 as part of Greying Ghost Archive Series (#1)

$5 / Buy from Greying Ghost Press

News of the Haircut is a chapbook by writer Peter Bergoef, published by Greying Ghost Press, as part of their Archive series. First published in 2007, this chapbook seems to touch on themes, such as love, loss, sadness, and the all too common feelings that are often described as an existential crisis, explored via a vague narrator like approach, giving the poems a somewhat personal feeling to them. These poems, which appear abstract at first, give the reader a series of images within images, presenting a version of themselves within the pages that one all too often tries to ignore.

other victims running their mouths

transmitting maths

through satellites

news of the haircut

the impending registration

over a few drinks served

What I notice here is an idea of a shared helplessness, which is shared through our connection and inhabitance of the internet. Transmitting maths through satellites, victims running their mouths, and being handcuffed to the chair, all give one the image of people who both need the internet, whether they want to admit it or not, and are afraid of their reliance on the internet. This seems to be a common theme among writers who interact with the online world, like Heiko Julien, Megan Boyle, or Tao Lin, writers who have become identified through the internet, and have also talked about loneliness and isolation through this medium. These writers seem to all depend on, and are sometimes repulsed by, the life led online, which reveals itself through their writing through the use of concrete and stark imagery. I think this is, in a way, become a reimagining of what existentialism posits, that life is absurd and meaningless, and that the only way for one to ‘break free’ from this crisis is to accept that life is absurd. So possibly, the contradiction of living ‘irl’ online is the absurdity that these writers are trying to accept.

and forceps have in common

so much cream colored wallpaper

so many dull rooms

Here he uses the images of birth, and the image of a straightjacket, implying being locked away in an asylum of sorts, to create an interesting juxtaposition between what “normal” is, and how one persons normal can be another’s “crazy.” The use of all lower caps is interesting as well, as it gives the poems a passive voice, sharing with the reader a feeling of hopelessness that comes from the non direct quality of the lines. In effect, the messages are both passive and active in the way they are structured and interpreted, which I find very interesting in all of the pieces.

Bergoef’s central theme, however, seems to be one of helplessness, or loneliness, and is again shown in the poem Awake. The use of short, simple lines, combined again with the lack of capitalization, combines to create an image that I can only describe as being “depressing,” but still not an unknowable image.

shallow breath

through a dim room

what was destroyed during sleep

now waits in the corner

forget dreams

eat cereal cold

take in coffee hot

souring the mouth

December 23rd, 2013 / 12:00 pm