25 Points: Kristen Stewart’s “My Heart Is A Wiffle Ball/Freedom Pole”

1. Plenty of celebrities have graced us with their beautiful words—Ally Sheedy’s Yesterday I Saw the Sun (Summit Books, 1991) teaches, “My insides slosh about like a nauseous ocean/It takes great gulps of air/Words from religious books/And Diet Cherry Coke to quiet the sound.” It is the wisdom of these cultural leaders—Jewel, Charlie Sheen, Suzanne Somers, Alicia Keys—and—James of House Franco, the First of Her Name, Queen of the Andals and the First Men, Lady Regnant of the Seven Kingdoms, Protector of the Realm, Khaleesi of the Great Grass Sea, Breaker of Chains, Mother of Dragons and Mhysa.

3. You cannot.

4. One job of the writer is to introduce neologisms into an otherwise very boring world. Alien space bats. Webinar. Astroturfing. Wardrobe malfunction. Brangelina. Affluenza. Kismetly. We need strong literary leaders like Kristin Stewart to push the next evolution of poetics.

5. How far does the looking glass reflect? Joyelle McSweeney, in a similar intense study of Stewart’s linguistics, noticed this: “‘kismetly’ is also a kind of inverted mirror writing of her own name (the k, i, s, e, t, the w inverted to m,)!”6. Similarly observed—is “Marfa” not a reference to Dan Flavin’s untitled (Marfa project), 1996?

7. Is it also not a reference to Atlanta’s MARTA terminal—or rather—the struggles of language—how the word distorts with a mouthful of blood, bone…freedom. Is this not done in the tradition of the great picaresque novel? Marfa, Marfa, beautiful Marfa! How the words travel like a train down the digital page—digital as moonlight!

8. The all-too-prosperous poetry market is overcrowded with the same bland literary journals publishing the same poets over and over. We need venerable institutions like Marie Claire to spread the gospel. Poetry from J-14! Poetry from Cosmopolitan! Poetry from Martha Stewart Living! Poetry from Golf World! Poetry from Handguns Magazine!

9. The future is now. Step the fuck aside, Blah Blah Review.

10. Why is “neon” a word that is exclusively owned by Beatniks/wannabe-atniks?

11. Should not words be owned by those with the most money? Basketball players, actors, meteorologists, CEOs—are these not the people in our community who should own the word “neon”?

12. As the great mathematician Robert Smith (later incorrectly attributed to Benjamin Franklin) once stated—”all cats are grey”. If all cats are grey—therefore—all moonlight must be digital. All bones are capable of being sucked pretty. All organ pumps are abrasive—and therefore (by Smith’s deduction)—can be perforated.

13. It is in our nature to spray paint everything that is known to us—this is fact—but what of the things we do not know? We require philosophers such as Stewart to guide us.

14. Both mythologically and scientifically-verified—devils are never done digging. They have also been observed in their natural environment 1) challenging mortals to fiddling contests 2) challenging deities to turn stone into bread and 3) challenging poets to write the best damn poetry they can write.

15. Stewart also writes—and take note—”He’s speaking in tongues all along the pan handle.” The “pan” in this line is a reference to the devil in the previous line—pan = Pan, the flute-playing god of the wild, who was later transformed (through the same ‘religious books’ Sheedy cites in her manuscript) into the Baphomet-envisioned devil we all know and love today. Iconoclast!

16. Iconoclast. Baphomet. Celebrity. Poet. Poet. Celebrity. Devil. Vampire. Wiffle® ball.

17. Freedom.

18. Do you believe in freedom? Do you believe “celebrity” is a different brand from “poet”. Why do you believe this, when you wish your poetry brought you celebrity?

19. Who decides how the Venn diagram overlaps—Kristen Stewart or you? Did you star in the world-renowned Twilight film franchise?

20. If “My Heart Is A Wiffle Ball/Freedom Pole” had been written by a darling of the New York poetry scene or your favorite MFA professor-cum-shaman, would you not have come running in its swift defense? [see 23.]

21. Would you not have come running in a pair of Balenciaga sneakers and sheer Zuhair Murad gown screaming?

22. Can you afford those things? Are you comfortable? Are you a poet? Are you a celebrity?

23. If yes, it’s a good poem. If no, it’s a good poem.

24. In a Yahoo!Answers (India Division) post from 6 years ago, user “Brainz” defined the opposite of Freedom as “slavery, captivity, imprisonment, confinement, restraint, among others!!!”. If you are not for the Freedom Pole, if you are not for the independence of poetry, of Kristen Stewart’s uninhibited language, of the right of every man, woman and non-binary gender person to sip a Starbucks Venti Frappuccino® Blended Beverage while tapping away at a 15‑inch MacBook pro with Retina display—then you are the enemy. An enemy of freedom—of poetry—of the world.

25. As fellow celebrity, philosopher and poet Billy Corgan once mused, “The world is a vampire.” This is certainly something that should be familiar to you of all people.

February 12th, 2014 / 5:56 pm

Forthcoming: war/lock by Lisa Marie Basile

Lisa Maria Basile, author of the chapbooks Triste (Dancing Girl Press) and Andalucia (The Poetry Society of New York), is one of the hardest working poets in New York. She is the Founding Editor and Publisher of Patasola Press, Assistant Editor of Fifth Wednesday Journal, and Editor-In-Chief of Luna Luna, my favorite online magazine.

On top of her editorial work, Basile works as a QA Assistant at MacMillan Publishers. She is a busy woman. Not too busy, it seems, to have written a third book, forthcoming this year on Hyacinth Girl Press.

I love war/lock, and believe it will be among the most important books of poetry released this year. Basile’s candid portrayal of abuse and survival is confessional in the best possible way, in that it is never self-indulgent and is, in fact, an act of generosity. Stories like these remind us that we, as trapped as we may feel in our respective subjectivities, are not alone.

2014 CALL FOR SUBMISSIONS

Two new responses to Calvin Bedient’s Boston Review essay “Against Conceptualism” that are worth a read:

Drew Gardner: Flarf is Life: The Poetry of Affect

ALL THE TEXTS I’D SEND YOU IF YOU WANTED TO GO TO A SERGIO DE LA PAVA TALK WITH ME ON DEAD RUSSIANS

…but then got ran over by a bus and died. No im totally kidding! but you really did get the flu and couldn’t join me.

The talk was at Housing Works, and it included two other speakers: David Gordon and Michael Kunichika.Your expectations were unclear: talk about Russian writers who, though they left us long ago, remain potent presences for readers and writers today. From Dostoevsky and Tolstoy to Vasily Grossman and Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky, we’ll learn about obsession, madness, realism, fables, and more, in an event with all the drama and pathos (well, at least some of the drama and pathos) of the great Russian novels themselves.

Here are all the texts I would have sent you, in chronological order and without clarifying who said what, because color-coordinating via SMS goes a step too far:

truth-seeking urgency intrinsic in russian lit

antithesis to beckett & writers who focused extensively on beauty of language

falling in love w/ english language, less plot driven urgency

dostoevsky similar to conrad in terms of truth-seeking urgency

multivocality of dostoevsky

there is no right, just different truths

dostoevsky threw the best literary parties (metaphorically speaking, as a creator)

proust s parties were too long, and maybe the guests were wearing better clothes

abstract psychological curiosity in motives, including abnormalities–>russian approach

going in depth for big questions, characters not being introverted

serialization of lengthy works, such as ‘war & peace,’ adds towards creating a broader debate. they become part of the broader debates occurring during their time

some compare the creation of microcosms of russian lit to ‘the wire’

comparing to british office, where they look at the camera at moments of despair but the viewer cannot do anything to help // to embarrasing dostoevsky characters

nabokov disliked dostoevsky for his “bad writing”

dostoevsky had a v diff approach to writing from nabokov: almost got executed literally, then was told he had another five years

that is also why dostoevsky did not pursue inanimate writing, unlike tolstoy (?)

nabokov didn t like music!

neither did dostoevsky !! (probably diff reasons)

saul bellow s ‘dean of december’–>similar urgency in truth-seeking (someone from the audience)

can reading a book be so vivid it appears like a different life?

if yes, it depends on willingness of writers to go to great lengths in creating characters who go too far, embarrass themselves/ are visceral

perhaps a key element that helps bring about the urgent truth-seeking: religion s role for the writers

religion, like their fiction, was trying to explain what goes on beyond the physical

nabokov s direct ancestor was dostoevsky s jailor. weird how he was not willing to cut him any slack, considering

dostoevsky was crowd-pleasing oriented bc he lived off writing

MONEY!!!

February 11th, 2014 / 5:20 pm

Short notice, but for those of you in Chicago, tomorrow night will see a plum event as the Danny’s Reading Series convenes, 7:30pm sharp at Danny’s in Bucktown (1951 W. Dickens, just off Damen). Reading will be Barry Schwabsky, Mark Yakitch, and the incomparable Virginia Konchan. As always, a DJ and dancing will follow.

…….Should Publishers Pull Gregory Sherl’s Books ??…….

***

On February 4th Kevin Sampsell made the following announcement on Future Tense’s Facebook page:

In light of recent of recent allegations of abuse, we’ve decided to remove Gregory Sherl’s book, Monogamy Songs, from our catalog. We hope that all people involved can heal and find peace.

Future Tense was not, though, the first press to remove a Gregory Sherl title from its catalog. The day before KMA Sullivan had announced on YesYes Books’ Facebook page:

In light of the allegations of abuse that have unfolded over the last few days and my beliefs surrounding these allegations, I have decided to pull Gregory Sherl’s book Heavy Petting from the YesYes Books catalog. I commend the women who have come forward. My sincerest hope is that everyone involved receive the support they need.

I’ve thought about this quite a bit in the last week (and discussed it with a few people I met with during my recent trip to Oakland and San Francisco) and while I agree with and would like to echo the last part of each of these announcements (“We hope that all people involved can heal and find peace” and “My sincerest hope is that everyone involved receive the support they need”) I’d like to think that If I was in a similar position I would NOT remove the book from my catalog.

This is to say that regardless of the allegations, or my beliefs surrounding them, I think the right thing would be to continue to make the book available to those who might want to purchase it. I feel where Future Tense and YesYes are coming from in this difficult, emotionally-charged situation– but for me the book is the book and If I thought it was good enough to publish then I’d like to think I would stand by it still (even if doing so made me wince).

***

On a related note The Oregon Trail Is The Oregon Trail, by Gregory Sherl, is still available from Write Bloody Publishing.

Milk and Filth

Milk and Filth

Milk and Filth

by Carmen Giménez Smith

The University of Arizona Press, October 2013

80 pages / $15.95 Buy from Amazon or The University of Arizona Press

The shinier the surfaces, the more the body leaves a smear on them, but contamination goes both ways. Increasingly, it’s what we feed on, even if it’s the parasite feasting on our dreams. It used to be that producer, distributor, and consumer were relatively separate entities, but the next economy wants them to be the same, as the object to be consumed becomes inseparable from its transmission, its dispersion, although what’s being sold and consumed are selves that the corporations are designing right next to the security apparatuses. “Your Data Is Political” is the title of a poem in Carmen Giménez Smith’s Milk and Filth describing the latest wave of colonization, which is related to what passes for culture these days—a user picking up someone else’s meme that the latter didn’t create while the whole process is datamined. But I like the accelerants—they make the fire go faster. And I’ll stick with poetry for now, because of any literary mode, its material components remain the most unruly, and the market still hasn’t figured out a way to capitalize on it, although just wait until they start charging for those MOOCs!

Poetry eludes efficiency, it shows choice to be fundamentally irrational, it embraces the misshapen, and so perhaps the most shocking line in Milk and Filth—a collection of poems aiming to transgress—is: “I write flabby poems, but fortunately my smart bombs cover them.” The problem with Conceptual poetics is that it’s too literal (or as Charles Bernstein says, “All poetry is conceptual but some is more conceptual than others.”), about a decade or two after the literal was transformed by the banality of the spectacle from discovery (“Q: And babies? A: And babies.”) to the dumb dumb club we’re all prodded to join. Perhaps poets should leave the documentaries to the historians and activists, which poetry can also be, but maybe if it’s not called art, which at least since Nirvana pop has relentlessly consumed. I’m willing to consider Lady Gaga an artist, but her music has never been anything but Top 40 fodder made by machines.

Elsewhere militarizing her metaphors, Giménez Smith understands the relationship between language and weaponry, the non-white body as an ongoing target as she seeks to “paint / more brown into the plot” and “wants mongrel dictions / to add to her arsenal.” But this intermixing is then intermixed with the deracination that occurs over generations as well as with the standardizing forms of expression and articulation, even when poetic: “the colonizing / worm is buried deep in you.” Indeed. Patriarchy is a motherfucker, and Milk and Filth veers more toward abjection than transgressiveness: “I’m debased but not that low,” she says, like William Pope.L sitting on a high toilet chewing the Wall Street Journal and washing it down with milk and ketchup, bio-economically redoubling the whiteness (and blood), or Cindy Sherman’s doll parts and viscera (an artist who along with the unfortunately overlooked Claude Cahun—the more radical version of Gertrude Stein—gets a nod in Giménez Smith’s endnotes to her poems). This (re-)claiming of the fragmented body turns inside out the totalizing gaze it has internalized; it floats to the surface the half-buried and the mostly unspoken, which are synonymous within regimes of the visible that change according to linguistic acts outside the normative, whether form or content, and usually the latter.

No wonder, then, that gender is treated as both fantasy and real. Milk and Filth opens with a series of poems entitled “Gender Fables” emphasizing the fabricated narratives that construct it, and one of these, “Susannah’s Nocturne,” might be read feminist after all the post(s)-:

looking for the other though

the other was Me. I free myself

through tree music, what some called

my morality-inflicted wound.

More to the story that I can’t get inside

or out of without rope. In both

the story and the trope, I am bride.

“I is another” is one of the oldest tricks in the book, but “the other was Me” illuminates the oppressive conventions women and women of color are still Subjected to on a daily basis, ideologically betrothed but remaining resistant. Milk and Filth is filled with references to enclosure and entrapment, including within an ocean stretching as far as the I can see. Feminist politics and poetry offer primary means of escape, although they, like everything else, are compromised, in the latter case by the degree of class privilege (the rope here and other places in the book) that surviving—i.e., making a living—from writing poetry (well, teaching, actually; and teaching it tenure-track, in fact) entails. For all of its general progressiveness, the poetry world doesn’t like explicitly political poetry, except within the spoken word community. While not overtly political, Milk and Filth triangulates ethnicity, gender, and class in ways both direct and nuanced that would seem to be the starting point for depicting social conditions in the early twenty-first-century United States, but mostly isn’t.

Midway through Milk and Filth, Giménez Smith inserts a complicated and sometimes contradictory “Parts of an Autobiography” written in 111 short prose sections, usually consisting of a sentence or two: “72. I’m the Shitty Friend writing valentines. I modify everything.” To say one thing and do another isn’t ideal, but to say one thing and desire something else is the political/discursive realm under which we are asked to live. In Milk and Filth, marriage, parenthood, politics, poetry, representations of the female body, etc., are riven with compromise, discomfort, even disgust, while simultaneously celebrated and embraced. (Giménez Smith’s 2010 “memoir” in fragments, Bring Down the Little Birds: On Mothering, Art, Work, and Everything Else, reads similarly.) One of the best poems in the book imagines an erotic encounter—a Blue Velvet-ish “place / of libidinous blackout”—separate from the cares and responsibilities of the everyday world with its mortgages and ceaseless office emails. Yet the very possibility of yet is the implicit yearning in this book, the sustaining metaphor of milk mingled with the non-figurative filth of how messy life really is.

***

Alan Gilbert is the author of two books of poetry, The Treatment of Monuments (Split Level Texts) and Late in the Antenna Fields (Futurepoem), as well as a collection of essays, articles, and reviews entitled Another Future: Poetry and Art in a Postmodern Twilight (Wesleyan University Press).

February 10th, 2014 / 10:00 am

Onward with a Grin: A Scene from Herzog by Saul Bellow

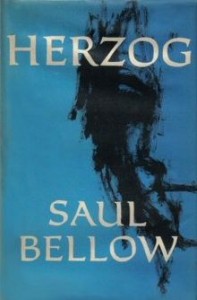

Herzog

Herzog

by Saul Bellow

Originally published by Viking Press, 1964

Buy from Amazon

In the lecture he delivered on the first day of classes at Wellesley College and Cornell University, Vladimir Nabokov tells of a Russian poet who was executed in 1921 because he would not stop smiling. Nikolai Gumilev died on an unknown day in August and, although his Soviet executioners did not know it, the crime for which he was first arrested was most certainly fabricated by their higher-ups. Still, Nabokov says, what truly irked “Lenin’s ruffians” was Gumilev’s steadfast smile, which he held even against the shock of the firing squad.

There is a cheerful morbidity in this anecdote that’s mixed from unpleasant truth, dark absurdity, and the inexorably joyous countenance of a man knowing he must die. There’s also a fundamental comedy of desperation on behalf of the Soviet goons who, at some point during the interrogations, must have flung up their arms up and said that if this poet won’t quit grinning then he has to go, so Gumilev unmindfully did.

This sort of comedy—with its helplessness, muddled terror, and insistent smile—is intertwined with the tragic in Saul Bellow’s fiction. Bellow intermingles sadness with laughter to create desperate comedies of hurt and self-humiliation, which attempt at first to allay pain through punchlines, by turning sorrow into farce. In art, the comic is usually superficial. Laughter is assigned the role of cure-all healer, a wheeler-and-dealer with the snake oil of stock gags and slapstick, where jokes are told to lighten the mood and reduce the gloom; yet Bellow pierces deeper.

For Bellow, laughter is not superficial, nor is it sorrow’s antithesis; for Bellow, laughter is the inherent human response to the incomprehensibility of life and all the flummoxing troubles therein. Comedy, then, becomes the involuntary sidekick that guides Bellow’s heroes who struggle closer to the crux of life’s inadequacies with vigor and a grin. The desperate comedy in Saul Bellow’s fiction forces the tragedy deeper by making it a little more palatable and accurate.

There’s a silly scene from Herzog that’s stuck in my mind for many years. It involves CPR and a monkey. Deep in the novel, Moses Herzog returns to Chicago to visit his young daughter who lives with his ex-wife. Before Herzog meets his daughter, he spends the night with an old friend, Luke Asphalter, a bachelor-zoologist who studies monkeys, and recently Herzog read in a magazine that when one of Asphalter’s subjects died he tried to revive it. “You must have been out of your mind, giving Rocco mouth-to-mouth respiration,” Herzog says. “That’s letting eccentricity go too far.” Asphalter says no one else’s death could have unraveled him the way Rocco’s did.

“You don’t mind if I smile,” Herzog apologized. “I can’t help it.”

“What else can you do?” Asphalter asks.

Is it mad to cherish an animal above all else? Is it insane that Asphalter says, “I was glad I had no wife or kids to hide these crying jags from,” because after Rocco died, he underwent a depression, quit showing at work, and let his beard grow so he’d better resembled the deceased simian? To Herzog it’s funny, devastating but funny, at least, he says, as “these painful emotional comedies” go.

It’s difficult to qualify the comedy in this scene—how it works, what to call it, what sort of reaction it requires; there are not one-word answers. There’s an element of black humor but it’s surpassed by Asphalter’s love and an element of absurdity that corrodes under the tears. There’s physical comedy in the memory of Asphalter attempting to resuscitate Rocco, though it seems less funny once Asphalter admits how much he needed the creature. The cartoon entertainment of a man giving CPR to a monkey mixes with the seriousness of loss. There’s death, loneliness, solitude, cordiality, and Moses Herzog’s continual bafflement as he tries to understand and fails. Asphalter says he’s been experimenting with different psychoanalytic treatments in an attempt to defeat his grief, but nothing helps. “Perhaps he was about to cry. I hope he won’t, thought Herzog. His heart went out to him,” Bellow writes. Then, as Asphalter describes how for one grief therapy session he pretended that he himself was dead—to overcome the sorrow of death by overcoming his own—Herzog thinks about Heidegger’s views and how “human life is far subtler than any of its models, even these ingenious German models. Do we need to study theories of fear and anguish?” This adds a tinge of humorous humility. The grand thinkers, as masterful as they may be, have no words to assuage the awfulness of the death of Rocco the monkey.

“You don’t mind if I smile?” “What else can you do?”

This exchange has guiding force. It’s the force of a smile that protrudes through, a smile mixed a startled, helpless laugh. The scene encapsulates the necessity of laughter, the deep soul-grunt of relief that laughter offers. Pain, loneliness, loss—these casual horrors are held at bay by the rebellious power of Herzog’s chuckle and grin. Laughter can stand up to misery and darkness; laughter is often an act of defiance. Shockingly, the worst of life can be shrugged off with a silly grin. “What else can you do?” These words have echoed in my mind for a long time. It’s a simple exchange, the kind that you could overhear on a bus or have with a friend about something very trivial or serious. Don’t mind if I smile? What else can you do? The facial expression that goes with “What else can you do?” is so particularly human it’s stunning.

Nabokov once described the Chekhovian hero as “a good man who cannot make good,” someone who “stumbles because he is staring at the stars.” One cold night in Chicago a while ago, Moses Herzog crashed on his friend’s couch. And there they were, two injured men laughing, two men who did their best but since when has that ever been good enough? The stars burn with infinite indifference to the plight of dreamers. The stars are beautiful but they cannot guide us.

“Unexpected intrusions of beauty. This is what life is,” Herzog thinks later, while he fills a sink with water and notices the “gray light” of the bathroom and the “almost homogenous whiteness” of the oval basin. The same holds for humor. Unexpected intrusions of laughter, of smiles, are what life is. They make the daily struggle slightly more bearable, knowing that at some point a chuckle, hearty haha, or quiet smile will arrive. Laughter is the necessary response to inexplicable loss and inevitable decay, a required reaction to all the regular and extravagant hurts that mark our days. What else can you do? Out of nowhere sometimes, like a ferocious roar, laughter will burst forth to remind us we are so fiercely, foolishly alive.

***

Alex Kalamaroff is a 26-year-old writer living in Boston. He works on the administrative team of a Boston Public Schools high school. You can read his other writings here or follow him on twitter @alexkalamaroff.

February 10th, 2014 / 10:00 am