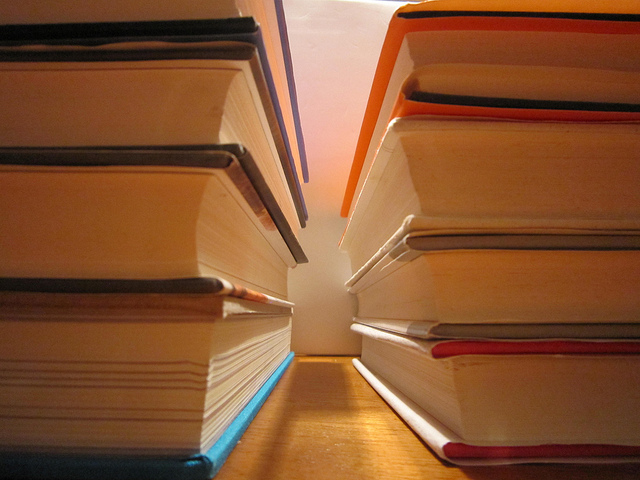

I’ve spent nearly all the hours since March in my apartment. So my attention in these last months has focused on, flitted by, or ignored my books—shelves and shelves of books—more often than in any other period of my life. Yet I’ve read little. I can blame distraction, fatigue, despondency—and I do. But the presence of my books, of so much paper and ink, is also for me a series of unanswered questions: What am I? What part of you do I serve? Do I serve anything at all?

Here is for me what a book has meant.

I’m five. The book is a cradle, but one held right in front of me. I can somehow be in it and outside of it. It’s a gift, a book—but a gift that doesn’t go away. A book is a place I can go anytime from anywhere. I’m not yet able to go there myself, or go alone, but I sense the possibility of this privacy. This possibility is scary, like a shadow of a bigger, stranger possibility that seems like the lives my parents live. An inexplicable life. A book is a path towards that life, but it’s also an escape from it because each book’s colors are so clearly more vivid, more real, than the life outside a book. I’m amazed that my parents don’t talk about this, this secret they open for me whenever we sit down to read.

I’m ten. I seek the secrets of books whenever I can. I’m convinced the worlds they contain are more real than the life of my bedroom, than the life of school. I suspect the books I run away into and the land of my back yard I run across are related in some deep way: that there is a shared wilderness in them, a wilderness which quietly and patiently rejects the status of the fence. I want desperately to make more of this wilderness. So I write. I write because writing and reading are both the act of bearing in my mind what must in all circumstances live. I know that the imagination is a realm which must be protected from the grays and metals and routines of the clothing racks, the grocery store, and homework. I know that what must live is being attacked by regular life, or what everyone else but regular readers call regular life. I hoard books, because of the perspicuity of my situation. And I hoard them because I love their shape, the grain of their pages, the smells they hide, the glint of their spines in every kind of light. I am a fugitive in the world because of the truth of books.

I’m fifteen. There are books, just a few, that scream the unsayable. This scream and its agony are a shelter. These books hide me. These books also make plain the fact that other people have worked so hard to reveal what’s hidden. That this is the role of a book: to reveal, to unearth, to dig up and tear open and point and stare. Reading and writing books is a way—the way, the only way—of being honest. I realize that not only must I continue to structure my life around books, but that books are escape tunnels leading away from the ordinary lies of living. I realize more vertiginously that I am responsible for building these tunnels. And that these tunnels must be beautiful—that books must be beautiful, as objects—because they must be habitable in case someone like me gets caught in them. Because, I suspect, we only ever get caught in them.

I’m twenty-one. The book is an event meant for other people. In making them, in editing and designing and soliciting them, I realize that books are events by which likeminded people are brought together. I view each book as an announcement, too: I have something important to say and I did my best to say it. Books can thus be judged by the social and financial context in which they were produced. Is this book’s announcement simply a commercial for its publisher, a little boon to the capital of that publishing company’s owners? If so, it can be scorned. Mocked. Or, ideally: ignored. The real shit, the real books announcing plain truths newly articulated, live among what our culture’s nervous gardeners call the weeds. The small press, the indie press: watchwords of those with good taste. Books are for and against: for the truth, for improvisation and innovation; against the dumb and redundant lies of the marketplace, against the formulaic and respectable. A book is an event for those rare good people to find and hold onto each other.

I’m twenty-six. A book is a piece of an infinite conversation, maddening in its scope and disunity, revelatory in its accidental harmonies which span thousands of years. To write or produce a book is to participate in this conversation. Yet the intensity and concomitance of this chaos and order makes walking through a bookstore or library exhausting, humiliating. A book, then, is a kind of sacrifice—because it is painful and costly to enter this conversation. The cost for a person who’s serious about books is that they can no longer speak with any grace during all those other conversations called “conversations” in day-to-day life: niceties, weather observations, constant nervous check-ins about the body and the mind and the state of the nation. Why? Because a great book is like a crystal whose form shapes great questions. In order to form these crystals, an author must permit themselves only the cold and arid air of solitude, distance, erudition, and honesty. Being open to this air requires a distance from one’s friends, one’s family. A book requires one’s blood.

I’m thirty-one. As I type this sentence, I’m looking at the rows of books I own. Despite making and spending money, I don’t like the sound of that: that these are my books. They’re not mine. They’re just temporarily living with me. And they do that: they live. They live because a book testifies to life. Not to the bland, back-of-the-cover-copy version of life, with its glib emphasis on the human and the joys and sorrows of social existence. A book testifies to the wider, stranger, more terrifying and fulfilling life we know when we are most inexplicable to ourselves. I’ve known this wider life when I’ve experienced any love whose existence I couldn’t fit into my vision of the order or disorder of things. Every gift points at this wider life; I’m sure of this. And I’m sure that each book is a gift.