Sucks to be a Mushroom: in which we read David Orr’s essay on poetic greatness until our hangover goes away

In this weekend’s NYT books section, David Orr weighs in on the sweat-to-brow question of whether Poetic Greatness is suffering–or has already suffered–its Peak Oil moment.

In October, John Ashbery became the first poet to have an edition of his works released by the Library of America in his own lifetime. That honor says a number of things about the state of contemporary poetry — some good, some not so good — but perhaps the most important and disturbing question it raises is this: What will we do when Ashbery and his generation are gone? Because for the first time since the early 19th century, American poetry may be about to run out of greatness.

Yikes. I keep wanting to be annoyed with this essay, and when Orr is throwing out gems like “Poetry has justified itself historically by asserting that no matter how small its audience or dotty its practitioners, it remains the place one goes for the highest of High Art[,]” it’s really hard not to just smack myself in the forehead, except my head already hurts for some seriously non-poetry-related reasons, so I’m going to save all self-flagellation for the repentance session I have scheduled for later this afternoon.

Anyway, despite the basic dopiness of claiming that poetry must at all times seek to obtain capital-i Immortality, and at that only by first obtaining to the status of High Art (whatever that is), Orr actually has some real points to make, and I can’t stay quite as annoyed as I’d like to. For one thing, he busts out this Donald Hall quote from 1983, where Hall, writing in the Kenyon Review, accused “contemporary American poetry” of being “afflicted by modesty of ambition.” I’m with Hall on this one, and with Orr for being with Hall–the fact that a full generation later (Taylor, Justin: b. 1982) nothing much has changed actually lends a lot of credence to Orr’s basic–yet still irritating–claim that perhaps the Poetical Climate Change is in fact irreversible.

Of course, another way to consider this same issue would be to consider poetry’s ever-more-marginal role in the culture not as a loss but as a shift– perhaps even an evolutionary response of the species to its new environment. On the other other hand, I’m also given to wonder whether things were really any different, or if Orr is recalling days of yore that never really existed. When people quote Shelley that “Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world,” it seems to me they typically misplace the stress on “legislators,” at the expense of the word in the sentence doing the most work–“unacknowledged.” And why should we want to be legislators of anything, much less the whole world? That whole notion, beneath its immediate surface-charm, stinks something tedious and bureaucratic. You can keep it.

Now, with that complaint entered into the record, let me say that I actually do share Hall’s (and Orr’s) disdain for unambitious poetry. I’m just not sure I see the problem as one of the state of the art. I think at any given time most work of art in a given medium will be unambitious, or else ambitious in all the wrong ways for all the wrong reasons. And let me be the first to say that any right/wrong judgment or success/failure judgment is bound to be at bottom a personal, subjective one. Absolute periplum, and no apology.

My theory is that High Art is hardly ever so often born as it is made–grown into, and especially looked back upon. Robert Burns and Francois Villon come to mind straightaway as examples of popular poetry that ascended bodily into High Art and now there reside forever. Also, of course, Dickinson and Whitman, who were never “low art,” but were totally marginalized and/or unknown in their own lifetimes. Now, of course, they’re the only thing any of us knows or cares to know about 19th century American verse. (How much Longfellow, Whittier and Bryant do YOU read?)

Orr makes a similar point-

What, then, do we assume greatness looks like? There is no one true answer to that question, no neat test or rule, since our unconscious assumptions are by nature unsystematic and occasionally contradictory. Generally speaking, though, the style we have in mind tends to be grand, sober, sweeping — unapologetically authoritative and often overtly rhetorical. It’s less likely to involve words like “canary” and “sniffle” and “widget” and more likely to involve words like “nation” and “soul” and “language.” And the persona we associate with greatness is something, you know, exceptional — an aristocrat, a rebel, a statesman, an apostate, a mad-eyed genius who has drunk from the Fountain of Truth and tasted the Fruit of Knowledge and donned the Beret of. . . . Well, anyway, it’s somebody who takes himself very seriously and demands that we do so as well. Greatness implies scale, and a great poet is a big sensibility writing about big things in a big way.

Obviously, Bishop v. Lowell is coming next, and so it comes. Orr quotes David Wojahn, who said that Lowell was “probably the last American poet to aspire to Greatness in the old- fashioned, capital-G sense.” I just don’t know that that’s true. Changing Light at Sandover, anyone? Dream Songs? Age of Huts (Compleat)? Ben Lerner’s forthcoming book-length poem, Mean Free Path? How about everything Campbell McGrath has ever attempted, not least his forthcoming book-length poem about the Lewis & Clark expedition? Or this outsize, tiny bizarre thing that Tao Lin has taken to making out of his life? We can sit around all day and argue over which of these works–if any–obtain the Grail of their quest, but I think the fact of their (and their authors) aspiring toward greatness is more or less undeniable.

Okay, here’s a quote I like. Orr writes that

Bishop was a great poet, if we take “great” to mean something like “demonstrating the qualities that make poetry seem interesting and worthwhile to such a degree that subsequent practitioners of the art form have found her work a more useful resource than the work of most if not all of her peers.” But our assumptions about how greatness should look, like our assumptions about how people should look, are more subtle and stubborn than we realize.

Right and right, I think. Okay, so moving on– blah blah more Lowell, blah blah more Bishop, ambivalent William Logan cameo, blah blah…

Which brings us to the point I mentioned earlier about the structure of the poetry world. Greatness isn’t simply a matter of potentially confusing concepts; it’s also a practical question about who gets to decide what about whom.

Ooh, now we’re getting somewhere!

For most of the 20th century, the poetry world resembled a country club. One had to know the right people; one had to study with the right mentors. The system began to change after the G.I. Bill was introduced (making a university-level poetic education possible for more people), and that change accelerated in the 1970s, as creative writing programs began to flourish. In 1975, there were 80 such programs; by 1992, there were more than 500, and the accumulated weight of all these credentialed poets began to put increasing pressure on poetry’s old system of personal relationships and behind-the-scenes logrolling.

Peak blurb oil!

It’s more of a guild now than a country club. This change has brought with it certain virtues, like greater professionalism and courtesy. One could argue that it also made the poetry world more receptive to writers like Bishop, whose style is less hoity-toity than, say, Eliot’s. But the poetry world has also acquired new vices, most notably a tedious careerism that encourages poets to publish early and often… Consequently, it’s not hard to feel nostalgic for the way things used to be; or at least, the way we imagine they used to be. And this nostalgia often manifests as a preference for a particular kind of “greatness.”

Yes, yes, yes. But don’t get settled yet, because orr isn’t going to stick with this theme. Instead, click through to page 3 on your screen for a very rough transition into a bizarre quasi-nativist screed about the “peculiar development in American poetry that has more or less paralleled the growth of creative-writing programs: the lionization of poets from other countries, especially countries in which writers might have the opportunity to be, as it were, shot.” Orr rags on Robert Pinsky for claiming that Czeslaw Milosz’s “laughter had the counter-authority of human intelligence, triumphing over the petty-minded authority of a regime.” “That’s one hell of a chuckle,” writes Orr. And yeah, the sentiment’s pretty windy, but no more or less than the average poetry blurb, and since Pinsky seems to have been talking about the man and not the work, why not let it slide? You should hear what people say about each other at weddings–to say nothing of funerals. You’d think we were all demi-gods, &c.

Oh, but we may as well let Orr make his point, right?

The problem isn’t that Pinsky likes and admires Milosz; it’s that he can’t hear a Polish poet snortle without having fantasies about barricades and firing squads. He’s by no means alone in that. Many of us in the American poetry world have a habit of exalting foreign writers while turning them into cartoons. […] How else, really, to explain the reverse condescension that allows us to applaud pompous nonsense in the work of a Polish poet that would be rightly skewered if it came from an American? Milosz, for instance, wrote many fine poems, but he was also regularly congratulated for lines like: “What is poetry which does not save / Nations or people? / A connivance with official lies, / A song of drunkards whose throats will be cut in a moment, / Readings for sophomore girls.” Any sophomore girl worth her copy of “A Room of One’s Own” would kick him in the shins.

Again, I think Orr’s onto something with this. That Milosz poem he quotes is awful–it’s naive, clunky, and yes, sexist. We’ve all witnessed the phenomenon of the fetishized foreign poet (*cough*Valzhyna Mort*cough*), whose reviews are all positive, and centered squarely on biography, with the work itself mentioned as an after-thought or else met only with decorous silence. But here’s the problem: he may be funny and he may be right, but I’m still not convinced that this particular sub-topic is relevant to Orr’s primary subject. As I’m so often forced to explain to my English 101 students: David, you would have done better to focus on the primary theme and push your analysis further, rather than bouncing from topic to topic. I’m looking for an original thesis and a compelling argument, not an exhaustive summary of the assigned reading.

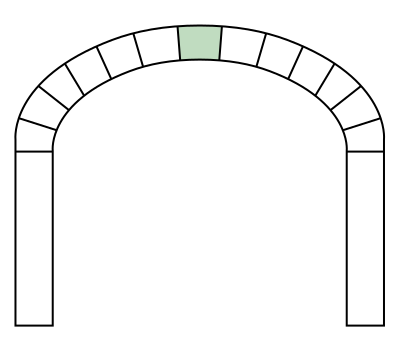

Well, as my students know (they better), a strong conclusion may re-inforce or recap the points made in the essay, but it’s main job is to push the argument that final step forward, to introduce the new, great idea which is the result of all the hard work you did throughout the course of the paper. Not gild for the lily, but the keystone for the bridge. And Orr, I’m happy to report, nails it bigtime-

It may be starting to sound as if greatness isn’t all that great; that it’s simply another strategy for concealing predictable prejudices that poets should forswear on their path to becoming wise and tolerant 21st-century artists. That is, however, almost the opposite of the truth. … When we lose sight of greatness, we cease being hard on ourselves and on one another; we begin to think of real criticism as being “mean” rather than as evidence of poetry’s health; we stop assuming that poems should be interesting to other people and begin thinking of them as being obliged only to interest our friends — and finally, not even that. Perhaps most disturbing, we stop making demands on the few artists capable of practicing the art at its highest levels. Instead, we cling to the ground in those artists’ shadows — John Ashbery’s is enormous at this point — and talk about how rich the darkness is and how lovely it is to be a mushroom. This doesn’t help anyone.

He’s right–and this is a great way to bring it all back home. I dig Ashbery, but we’ve all been behaving for far too long as if poetry stopped when he stopped–a formulation that’s especially bizarre since Ashbery hasn’t stopped and doesn’t seem as if he means to anytime soon. It’s great that he’s got his Library of America edition–hell, it’s great that we’ve got it–but there’s still more on Heaven and Earth than’s dreamed of in his etc.

There seems to be a fundamental misunderstanding of Ashbery, which causes young poets to view his personal style as a genre or mode that’s free for the joining, because it’s fun and looks like it’s easy, while at the same time viewing his status as a sort of terminal point or high-water mark: ooh he wrote a book that won the awards trifecta; ooh he’s in his 80s and appearing on MtvU.

In the post-Peak Poetry Status world, we will seek status from alternative sources, such as geo-thermal and wind. The main difficulty with these status technologies lies in transmitting status from the site of production to the status grid.

What this looks like to me is a basic case of crossed wires. Take whatever you want from Ashbery–pleasure, lessons, tricks; his work is a vast treasure-house, after all–but understand that a poet’s personal style is always a terminal point. Making a genre out of Ashbery is a mistake, and it’s a mistake that’s been happening for a generation now, and it’s a mistake that only ever leads to one thing: watered-down, derivative pseudo-Ashbery. (The same goes for Tao Lin’s legion of ditto-heads, though smart money says that crew won’t get its hands on enough keys to enough academic buildings to ever cause anybody any real trouble.)

The best way to understand Ashbery is as the lion in the path–love him or lump him, there he is. But let’s assume that you are an admirer, that you understand the Ashbery-lion in the same way that Beckett understood Joyce, which was later the way Barthelme understood Beckett. A majestic, noble creation, beautiful to behold and terrifying in its power: you admire it, you get as close as you can to it, you want to see it, after all, and then you run in the other direction before it eats you the fuck up. Because that’s what greatness does if you let it–consumes you, defeats you, rips your head off and feasts on your insides. (How many times has a book you truly loved left you feeling melancholy, because you came away from it feeling like you’d never write anything as powerful? This is how I feel whenever I read Woolf’s The Waves.)

It’s not Ashbery’s style you want to aspire to–that’s been done, and now done and done–it’s his status. Why isn’t greatness possible? Are you saying you can’t wake up every day God gives you, and on that day do your absolute best to produce the best work you’re capable of producing? Are you saying you can’t write a book as good as Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror? You know what? Maybe you can’t. But there’s only one way to find out. The goal is not to sneak by the lion, or feed him enough meat that he lets you pass. Neither is it to sit down in the path at a safe distance and watch the lion as it goes about its business. The goal is to become the lion– let the next guy see you sitting there, and turn tail for fear of his life.

Greatness is hungry.

Tags: David Orr, John Ashbery, poetic greatness

You wrote this hungover??!!! Holy crap.

Ambition and greatness. Ambition to be great. Hmmm. But see, this is WHY I have issues with (hate me) Ulysses. You can just feel and smell the desire to be “great” and I don’t like that experience. I want greatness to just be, to smack me up. I don’t want to feel the author’s desire to be great. Also, everyone? I am wrong and you are all right.

I’m not even that hungover today and yet I can’t really wrap my head around this too much. I liked this very much. I plan on having a very bad hangover on monday so maybe then I will be able to chew on this stuff again and say something other than holy crap.

justin, the inner workings of your mind are like clarified butter: i wanna roll around in it.

in the after-glow of the deconstruction, the old paths toward greatness have been dismantled. there are no more over-arching, monolithic, unified theories toward which and down from which the authority of grand truths or sentiments can be dispensed like pez. the notion of greatness itself has been dismantled. it is simultaneously liberating and leaves an awful hangover (which hasn’t seemed to have affected your efficacy none). andrei tarkovsky’s madman, as he poured gasoline on himself, shouted out ‘there are no greats left’, before setting himself on fire. it is a supreme nostalgia.

if greatness is to be found in this day and age, it’s not, as orr pointed out, by employing grand, sweeping sentiments. but as you mentioned, more existentially so–an intense engagement with being alive as a fucked-up, confused sentient trying to make its way in this world, and serve as a conduit of as much temporal radiance as possible. to read from a poet today i don’t want to hear more of the old school grandiosity, inane hyperboles and lofty over-simplifications.

the old paths to greatness have been blocked, neither the profound nor the iconoclastic are much of a viable root: the former is a fractured mirror and the latter a dry well. it’s not surprising that the ‘sense of greatness’ is lulling. the idea itself needs to be reinvented if it is going to continue to be valid. and i think slowly it will be along the lines you propose: it is propelled by the same drive (life, growth, mitochondriac wharehouses), and just needs a new egg-shell to break out of.

justin, the inner workings of your mind are like clarified butter: i wanna roll around in it.

in the after-glow of the deconstruction, the old paths toward greatness have been dismantled. there are no more over-arching, monolithic, unified theories toward which and down from which the authority of grand truths or sentiments can be dispensed like pez. the notion of greatness itself has been dismantled. it is simultaneously liberating and leaves an awful hangover (which hasn’t seemed to have affected your efficacy none). andrei tarkovsky’s madman, as he poured gasoline on himself, shouted out ‘there are no greats left’, before setting himself on fire. it is a supreme nostalgia.

if greatness is to be found in this day and age, it’s not, as orr pointed out, by employing grand, sweeping sentiments. but as you mentioned, more existentially so–an intense engagement with being alive as a fucked-up, confused sentient trying to make its way in this world, and serve as a conduit of as much temporal radiance as possible. to read from a poet today i don’t want to hear more of the old school grandiosity, inane hyperboles and lofty over-simplifications.

the old paths to greatness have been blocked, neither the profound nor the iconoclastic are much of a viable root: the former is a fractured mirror and the latter a dry well. it’s not surprising that the ‘sense of greatness’ is lulling. the idea itself needs to be reinvented if it is going to continue to be valid. and i think slowly it will be along the lines you propose: it is propelled by the same drive (life, growth, mitochondriac wharehouses), and just needs a new egg-shell to break out of.

Justin,

I remember my first class at New School with Liam Rector (who was also under some serious Donald Hall influence) lecturing and demanding “greatness” and you can’t imagine (or maybe you can as you went there too) how resistant and horrified most of them were to aspire to “greatness.”

Anyways, happy to see that you mentioned Dream Songs- definitely greatness and I’m looking forward to Lerner’s new book as well.

Justin,

I remember my first class at New School with Liam Rector (who was also under some serious Donald Hall influence) lecturing and demanding “greatness” and you can’t imagine (or maybe you can as you went there too) how resistant and horrified most of them were to aspire to “greatness.”

Anyways, happy to see that you mentioned Dream Songs- definitely greatness and I’m looking forward to Lerner’s new book as well.

Steven- I didn’t take Liam’s class, but Nick Adamski tells a great story about Liam (I’m going to get the details wrong on this) demanding that his class tell him who makes these kinds of decisions? The key quote might have even been “who is in charge of the culture?” or something like that. But the point is that when nobody answered him, he yelled at them that it was HIS decision, because they had all just missed their opportunity to assert that the power lay in their own hands.

keith n b- thanks for the kind words. and yeah, i hear 100% where you’re coming from, but with all due respect it’s sort of exactly the kind of thinking i’m arguing against. tarkovsky’s man on fire makes his claim, then removes himself from the conversation altogether- so his claim is unanswerable, point for him, but he also isn’t there to demand an answer, so i don’t have to spend too much time thinking about what he said. point for me (us).

Let’s put poetry aside for a second. In prose-land, the standard claim is that Beckett may well have been the last big-g Great One, but I would argue that the best work of two of his most attentive disciples (that would be Barthelme & DeLillo) stands up to anything Beckett ever wrote. Blake Butler will tell you that David Foster Wallace was a Great, and he’s far from the only one. So maybe this isn’t a problem with literature in general, but uniquely with poetry, though again, I think the problem is essentially self-correcting. Something will be remembered as the Best of This Era–its up to us to make each other work harder to produce better things, so that the standard for Bestness gets pushed higher. Maybe the best this era produces will be minor works– that happens to some eras. But I don’t see any reason to settle for the fate in advance.

The alternate title for this essay was “David Orr calls “Worstward Ho!” because I wanted to bring in Beckett’s injunction to “fail better” as a sort of model for the approach I’m advocating people take to their art. Any sort of ambition, motive, aspiration, etc has to be directed *toward* something, so why not Greatness?

I’m not saying you should sit down with a copy of “The Waste Land” and go “okay, Eliot makes the claim for April, so I’m going to argue for May and show him up…” But seriously, what would a Major Work of Literature both appropriate to its moment and able to transcend that moment, really look like? Who is going to write it? There’s no reason to assume it will have the same form, focus, or concerns as Major Works which preceded it, though it may account for them in some way–possibly in the form of a radical break, or inversion.

Also, let’s distinguish between Major Works and Literary Greatness. Kerouac achieved Literary Greatness as a figure, without producing–in my opinion–anything worthy of the status of Major Work, though obviously some of it is called by that name.

Tao Lin has produced a lot of work I’ve really appreciated, and some of which I think is excellent. Time will have to decide what if any Major Canonical Works he produces, but in terms of developing into a figure of Literary Greatness, I think you have to give it to him. And all the more so if he makes you fucking crazy or you think he sucks. The weird stunts, publicity-hounding and everything else need to be looked at in terms of his own love of Pessoa. In an era of instantaneous communication and absolute exposure, where radical self-centeredness is more or less the norm, it makes sense that our Pessoa would be a person who, instead of quietly developing heteronyms and alternate identities in the comfort of hermitude, becomes instead a complete externalist of the internal self: Tao essentially performs the act of extreme neurotic privacy in public all the time: including the alternating cravenness and intentional self-sabotage of which we’re all capable. His work emerges from his life like a fish jumping out of water and then crashing back in like the same–a kind of disappearance not into darkness but into the brightness of the flashbulb, the computer screen, etc.

Steven- I didn’t take Liam’s class, but Nick Adamski tells a great story about Liam (I’m going to get the details wrong on this) demanding that his class tell him who makes these kinds of decisions? The key quote might have even been “who is in charge of the culture?” or something like that. But the point is that when nobody answered him, he yelled at them that it was HIS decision, because they had all just missed their opportunity to assert that the power lay in their own hands.

keith n b- thanks for the kind words. and yeah, i hear 100% where you’re coming from, but with all due respect it’s sort of exactly the kind of thinking i’m arguing against. tarkovsky’s man on fire makes his claim, then removes himself from the conversation altogether- so his claim is unanswerable, point for him, but he also isn’t there to demand an answer, so i don’t have to spend too much time thinking about what he said. point for me (us).

Let’s put poetry aside for a second. In prose-land, the standard claim is that Beckett may well have been the last big-g Great One, but I would argue that the best work of two of his most attentive disciples (that would be Barthelme & DeLillo) stands up to anything Beckett ever wrote. Blake Butler will tell you that David Foster Wallace was a Great, and he’s far from the only one. So maybe this isn’t a problem with literature in general, but uniquely with poetry, though again, I think the problem is essentially self-correcting. Something will be remembered as the Best of This Era–its up to us to make each other work harder to produce better things, so that the standard for Bestness gets pushed higher. Maybe the best this era produces will be minor works– that happens to some eras. But I don’t see any reason to settle for the fate in advance.

The alternate title for this essay was “David Orr calls “Worstward Ho!” because I wanted to bring in Beckett’s injunction to “fail better” as a sort of model for the approach I’m advocating people take to their art. Any sort of ambition, motive, aspiration, etc has to be directed *toward* something, so why not Greatness?

I’m not saying you should sit down with a copy of “The Waste Land” and go “okay, Eliot makes the claim for April, so I’m going to argue for May and show him up…” But seriously, what would a Major Work of Literature both appropriate to its moment and able to transcend that moment, really look like? Who is going to write it? There’s no reason to assume it will have the same form, focus, or concerns as Major Works which preceded it, though it may account for them in some way–possibly in the form of a radical break, or inversion.

Also, let’s distinguish between Major Works and Literary Greatness. Kerouac achieved Literary Greatness as a figure, without producing–in my opinion–anything worthy of the status of Major Work, though obviously some of it is called by that name.

Tao Lin has produced a lot of work I’ve really appreciated, and some of which I think is excellent. Time will have to decide what if any Major Canonical Works he produces, but in terms of developing into a figure of Literary Greatness, I think you have to give it to him. And all the more so if he makes you fucking crazy or you think he sucks. The weird stunts, publicity-hounding and everything else need to be looked at in terms of his own love of Pessoa. In an era of instantaneous communication and absolute exposure, where radical self-centeredness is more or less the norm, it makes sense that our Pessoa would be a person who, instead of quietly developing heteronyms and alternate identities in the comfort of hermitude, becomes instead a complete externalist of the internal self: Tao essentially performs the act of extreme neurotic privacy in public all the time: including the alternating cravenness and intentional self-sabotage of which we’re all capable. His work emerges from his life like a fish jumping out of water and then crashing back in like the same–a kind of disappearance not into darkness but into the brightness of the flashbulb, the computer screen, etc.

Phenomenal post, Justin!

Phenomenal post, Justin!

Inspiring, too. I’m going back to work.

Inspiring, too. I’m going back to work.

justin, perhaps my comment was poorly articulated. essentially i was agreeing with you. or at least i thought i was.

in the first paragraph i was simply pointing out that any perceived lack of greatness (e.g. tarkovsky (whom i think was great)) has to do with the fact that the greatness of this era would in no way resemble that of the modernists or postmodernists, and so might not be recognizable until enough time has passed to perceive the ‘best of this era’ as you said. or like you said, maybe the representatives of this era will only be minor works. but precisely because we are in a new era, the cultural context will redefine the meaning of greatness.

regardless of era, i believe you nailed the invariable trait of greatness: “Literature both appropriate to its moment and able to transcend that moment.”

yeah man, i’m all for it, the lion’s roar reminds me both of nietzsche and of trungpa rinpoche. i used to go out in the middle of the woods (so i wouldn’t get locked up again) and practice roaring. someday i hope to teach my fingertips to do the same.

your post was reassuring. whatever feelings of greatness inspire me stems from a desire to commune with the presence inside of and beyond me, to drive to the core and with my janusian lungs convert carbon dioxide to oxygen.

justin, perhaps my comment was poorly articulated. essentially i was agreeing with you. or at least i thought i was.

in the first paragraph i was simply pointing out that any perceived lack of greatness (e.g. tarkovsky (whom i think was great)) has to do with the fact that the greatness of this era would in no way resemble that of the modernists or postmodernists, and so might not be recognizable until enough time has passed to perceive the ‘best of this era’ as you said. or like you said, maybe the representatives of this era will only be minor works. but precisely because we are in a new era, the cultural context will redefine the meaning of greatness.

regardless of era, i believe you nailed the invariable trait of greatness: “Literature both appropriate to its moment and able to transcend that moment.”

yeah man, i’m all for it, the lion’s roar reminds me both of nietzsche and of trungpa rinpoche. i used to go out in the middle of the woods (so i wouldn’t get locked up again) and practice roaring. someday i hope to teach my fingertips to do the same.

your post was reassuring. whatever feelings of greatness inspire me stems from a desire to commune with the presence inside of and beyond me, to drive to the core and with my janusian lungs convert carbon dioxide to oxygen.

keith n b- yeah, that was totally my mis-read. we are absolutely on the same page. thanks for sticking with me, man.

roaring? i could see that being an amazing feeling. when none of my roommates are home (or i just think they’re not but turn out later to be wrong–oops) I put music on as loud as i can and sing along to it as loud as i can, usually Magnolia Electric Co. because as far as I’m concerned most of Jason Molina’s songs are basically prayers. It feels amazing. I always wonder what the lawyer downstairs thinks about it.

keith n b- yeah, that was totally my mis-read. we are absolutely on the same page. thanks for sticking with me, man.

roaring? i could see that being an amazing feeling. when none of my roommates are home (or i just think they’re not but turn out later to be wrong–oops) I put music on as loud as i can and sing along to it as loud as i can, usually Magnolia Electric Co. because as far as I’m concerned most of Jason Molina’s songs are basically prayers. It feels amazing. I always wonder what the lawyer downstairs thinks about it.

high art? david orr? who are these people, man?

high art? david orr? who are these people, man?

I loved this. This was fantastic. More like this, yes, yes, yes.

This from Orr especially resonated:

“When we lose sight of greatness, we cease being hard on ourselves and on one another; we begin to think of real criticism as being “mean” rather than as evidence of poetry’s health; we stop assuming that poems should be interesting to other people and begin thinking of them as being obliged only to interest our friends — and finally, not even that.”

People descend into this far too often. And then make categorical statements about how all of art is meaningless, etc, etc, which I think kind of devalues the conversation if you aren’t doing it sincerely or are just using it as a way of dodging reaction or criticism.

Regarding Tao Lin and his weird stunts, I can see how they would add to the legend or whatever his “legacy” ends up becoming… and how he even embodies the current social climate– but is greatness an embodiment of what is happening “now” or is it a yearning or expression of something else, a pulse unexpressed, which might take us forward? I don’t have the answer to that. Obviously it could be both, and it’s hard to comment on Tao specifically when we don’t have a complete body of work… I just wonder if taking his stunts into consideration isn’t the exact same thing as praising a foreign poet for their life more than their work.

To me at least (and I haven’t read anything significant of his yet– yeah, I know) it seems like Tao’s stunts and attitude are cynical and maybe even a little bit cheap (less than “great”) but I don’t know really, I can’t talk about anything more than my perception of him as a man at this point.

I loved this. This was fantastic. More like this, yes, yes, yes.

This from Orr especially resonated:

“When we lose sight of greatness, we cease being hard on ourselves and on one another; we begin to think of real criticism as being “mean” rather than as evidence of poetry’s health; we stop assuming that poems should be interesting to other people and begin thinking of them as being obliged only to interest our friends — and finally, not even that.”

People descend into this far too often. And then make categorical statements about how all of art is meaningless, etc, etc, which I think kind of devalues the conversation if you aren’t doing it sincerely or are just using it as a way of dodging reaction or criticism.

Regarding Tao Lin and his weird stunts, I can see how they would add to the legend or whatever his “legacy” ends up becoming… and how he even embodies the current social climate– but is greatness an embodiment of what is happening “now” or is it a yearning or expression of something else, a pulse unexpressed, which might take us forward? I don’t have the answer to that. Obviously it could be both, and it’s hard to comment on Tao specifically when we don’t have a complete body of work… I just wonder if taking his stunts into consideration isn’t the exact same thing as praising a foreign poet for their life more than their work.

To me at least (and I haven’t read anything significant of his yet– yeah, I know) it seems like Tao’s stunts and attitude are cynical and maybe even a little bit cheap (less than “great”) but I don’t know really, I can’t talk about anything more than my perception of him as a man at this point.

Justin, this is an awesome response. I’m awaiting a book of critical essays by JT. There’s been a little e-mail discussion going on among me and several friend-poets, and I think the consensus is that though Orr acknowledges that ‘It may be starting to sound as if greatness isn’t all that great; that it’s simply another strategy for concealing predictable prejudices that poets should forswear on their path to becoming wise and tolerant 21st-century artists,’ he still sounds like he’s mocking the wise and the tolerant, and isn’t offering any real alternative to the old tenets of greatness. Sure, one should strive to write really good shit, but when an old white dude starts talking to me about Ambition, I have a flashback to an alpha-male resume expert telling me I should be more Aggressive in my job search; in other words, I want to kick him in the shins and page Valerie Solanas, then offer him (and myself) an anti-ego pill. Think more about the poems you write than about the poet you are, Orr. Or?

Justin, this is an awesome response. I’m awaiting a book of critical essays by JT. There’s been a little e-mail discussion going on among me and several friend-poets, and I think the consensus is that though Orr acknowledges that ‘It may be starting to sound as if greatness isn’t all that great; that it’s simply another strategy for concealing predictable prejudices that poets should forswear on their path to becoming wise and tolerant 21st-century artists,’ he still sounds like he’s mocking the wise and the tolerant, and isn’t offering any real alternative to the old tenets of greatness. Sure, one should strive to write really good shit, but when an old white dude starts talking to me about Ambition, I have a flashback to an alpha-male resume expert telling me I should be more Aggressive in my job search; in other words, I want to kick him in the shins and page Valerie Solanas, then offer him (and myself) an anti-ego pill. Think more about the poems you write than about the poet you are, Orr. Or?

Part of the problem with Greatness, is the necessity for any who aspire toward it to self-mythologize. Tao Lin probably aspires to Fame and Celebrity and maybe Greatness, but look how much prostitution he has to undertake on his way. And Lerner, a much better writer, still has to hustle, from having friends review his work to having his teacher nominate him for the National Book Award. Both poets have that necessary ingredient, Ambition, and Ego, and it’s what kills me about the current scene. How many female poets did you list, as answer to Orr’s piece? Zero. It’s considered inappropriate if a woman poet hustles the way Lin and Lerner do. When they do it, we sit on our hands, forget to point out the nepotism and/or insane self promotion, and call it ‘balls.’

Part of the problem with Greatness, is the necessity for any who aspire toward it to self-mythologize. Tao Lin probably aspires to Fame and Celebrity and maybe Greatness, but look how much prostitution he has to undertake on his way. And Lerner, a much better writer, still has to hustle, from having friends review his work to having his teacher nominate him for the National Book Award. Both poets have that necessary ingredient, Ambition, and Ego, and it’s what kills me about the current scene. How many female poets did you list, as answer to Orr’s piece? Zero. It’s considered inappropriate if a woman poet hustles the way Lin and Lerner do. When they do it, we sit on our hands, forget to point out the nepotism and/or insane self promotion, and call it ‘balls.’