“ultimately beautiful”: an Interview with Steve Roggenbuck

I saw Steve Roggenbuck read at Stephen Dierks house during AWP week he stood on top of something, I can’t remember what, he is small, his physical presence not very dominating. But he stood up there and took control of the audience, yelling 666 and Justin Bieber and all kinds of weird shit. The audience stood there, completely enthralled. People were yelling and screaming during the whole reading, people were extremely excited to be at a poetry reading.

According to AD Jameson Steve Roggenbuck would be considered a New Sincerist and the question has been asked, if writing in such a sincere manner can be prolonged over a long career. I think it can, because sincerity is transitory. The writing is Buddhist in that way, an acceptance of endless change, the impermanence. We can be convinced of truth at times/later/that truth becomes false/we forget those beliefs. For three years we read one type of books/then move onto another/then move onto another. We move from the country/to the city/we fall in love/we fall out of love/do it again/we don’t have sex for two years/we meet a sado maschocist and get choked/we have kids/watch them grow/we wash diarrhea off her our naked father because he is sick and dying/we become concerned about insurances/it goes/on on on. Roggenbuck’s first book I am like October when I’m Dead were short little poems with a tibit of sentimentality. Helvetica was this blitzkrieg of weird ass flarf lines. And Crunk Juice was an intensely designed chapbook with longer poems, using more poetic devices with a higher emphasis on sound. These changes, are not just the changes of a writer, but Steve Roggenbuck changing before us, we are getting older with him. He asks us to join him, on his journey through life, seems a little like reality television, but who wouldn’t want a reality television full of really emotional well-read people.

NC: I think what you don’t do is one of the reasons you have made such a ‘big splash.’ Like you didn’t go down the depression road when writing, which I think invited a lot more people into the alt-lit scene. Because not everyone is suffering from depression and existential crisis all the time. Did you consciously reject the depression route or just find it not your style? READ MORE >

Let Us Celebrate the Anniversary of Vanessa Place’s Escape From the Womb

Poet Kenneth Goldsmith has said Place’s work was “arguably the most challenging, complex and controversial literature being written today,” and poet Rae Armantrout has remarked, “Vanessa Place is writing terminal poetry.” Bebrowed’s Blog said Place is “the scariest poet on the planet.” Anonymous on Twitter said, “Vanessa Place killed poetry.”

To remember this idea after waking: An Interview with Christopher DeWeese

Recently released from Octopus Books, Christopher DeWeese’s The Black Forest is a slim, refreshing volume, intent on bending time and expectation in language carefully measured, calm and clear. It was described by James Tate as such: “These poems sock home truth and enact poetic somersaults that leave me out of breath. It’s a pleasure to recommend them to anyone brave enough. Chris DeWeese is the real thing, a poet true to his calling.”

BB: The Black Forest is your first book, while also one of many you have written over the years in coming up to it. Did you know this book was a specific project when you began the poems in it, or how did it come together as what it is?

CD: For three years while I was getting my MFA I only worked on this one thing, a sequence of poems called The Confessions. When I started that project, I had just been blown absolutely away by Berryman’s The Dream Songs and Berrigan’s The Sonnets, and I had this feeling that maybe writing a book-length poem was the solution to all of my problems. I remember at the time being very confused about how to write poems: before grad school, I had been writing pretty much on my own for a few years, and the poems I wrote were not very good, and all of a sudden I was around all of these people who seemed to already have really confident, singular styles, and I felt like I didn’t know what I was doing or (more importantly) even what I wanted to do in writing poetry.

The most helpful thing about just writing this one project for so long was that it gave me a stable architecture of form to write into. And that was huge for me, because I felt like just starting to write an individual poem was a process weighted down with huge decisions, decisions about form and content that needed to have complicated rationales lurking behind them. So for three years, I didn’t have to worry about that, because I was totally committed to just working on this one thing. And by the time I finished working on it, I was ready to realize that the way I had thought about the process of making poems before was actually totally wrong (for me at least) and that one good and valid way of composing poetry is to just start writing and to see what happens. So when I started writing the poems that would eventually compose The Black Forest, there were no ideas about the poems going together or belonging together as a certain project: there was just this feeling of freedom, and a desire to be loose and wild with my imagination. I had just started running when I began to write these poems, and a lot of the first lines would occur to me while running, and then I would spend the rest of the run saying the line over and over to myself to try and remember it, and by the time I got home the line would have achieved this power, this importance borne of repetition, so I’d write it down and often the rest of the poem would come out very quickly. And over time, I did realize that a lot of the poems I was writing belonged together, that they shared a lot of language and concerns, and it felt good to realize that the consistency of the book had come together in a fairly organic way. READ MORE >

Unfold is the wrong word: An Interview with Bhanu Kapil

To read Bhanu Kapil‘s work is to witness it taking shape. It is as if she writes just for us, closing the space between reader and writer. That space, whose medium is the page, is cared for as one cares for a body. It takes on a consciousness. We feel comfortable, cared for, led calmly to scenes beautiful and horrific, and we trust her to be our guide. Kapil’s work is not something the reader can passively consume, it is something of which you are a part. Her novels move poetically; they are fragmented but do not surrender a narrative. She doesn’t just show us that we are looking through a window, she opens it and decorates it by setting photographs on the sill along with flowers, quotes, cups of tea and coffee; she paints it orange and red and yellow and green; she lets the outside world spill in: wind, leaves, mud, shouts of wolf-girls playing in libraries, and conversations between immigrants and cyborgs. Her narrators are liminal and migratory and her worlds strange, unstable, and yet familiar.

Bhanu Kapil is the author of four full-length works of prose/poetry: The Vertical Interrogation of Strangers (Kelsey Street Press, 2001), Incubation: a space of monsters (Leon Works, 2006), humanimal [a project for future children] (Kelsey Street Press, 2009), and Schizophrene (Nightboat Books, 2011). This summer, she is teaching a workshop at the intersection of performance and the novel at Naropa University’s Summer Writing Program. During the year, she teaches full-time at Naropa’s Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics in Boulder, Colorado, and part-time for Goddard College in Plainfield,Vermont. She also maintains a part-time practice as an integrative bodyworker, focusing on Ayurvedic treatments. Born in the UK to Indian parents, Bhanu, “dreams of turning into a female Michael Ondaatje, writing proper novels in her garage, which has been converted into a solar-heated hut. If that doesn’t work out, she will continue to write anti-colonial literatures and pioneer new spa treatments. Currently, she is working on a paste of chickpea flour, turmeric and rose petals that is guaranteed to brighten even the most winter-bound skin.” For many years, she blogged at WAS JACK KEROUAC A PUNJABI but then, abruptly, stopped.

The interview with conducted through email. READ MORE >

Book + Beer: Tom Wolfe and St. Sebastiaan Belgian Ale

The rain stopped. At that point the guy (knobby head like an asteroid) from the repair shop comes out to tell me that my baby-baby scooter (sweet ride, ODI grips, Kelsey throttle, a desperation of chrome) needs another ninety-four bucks’ worth of repairs, even though they just got finished fixing it, or saying they fixed it, and he says what do you want to do? And I say I don’t want to do anything, Mr. ASS (teroid), you owe me a scooter I can drive away from this crime scene after the last two hundred bucks I spent here, and he says it’s not their fault, it’s a piece-of-shit scooter that hasn’t been properly maintained, and I say hey, I am not paying another cent for repairs that don’t repair, and he says okay, fine, they’ll junk it, and I say okay, fine, junk it then, it’s junk now anyway since you guys mangled it, and he stomps off, so there I am, up a creek and scooterless. So anyway I call my brother, sit down, and finish reading The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. Get in my brother’s car (a brown turd Kia) and he hands me a beer and sees the pink/yellow/retina-detachment bus of a book cover and prowls the title and says, “Is that the kind of shit people who drive scooters read?”

The bottle is ceramic. It has an oatmeal look. I thought, “Oatmeal.” Oatmeal is an OK word to have conked in your kettle while drinking Belgium ale. Has a slight bottled taste to it and that makes some sense. The finish was bitter. I like bitter finishes, I do. I like gas station coffee and going to bed after a big, crazy fight. I find it comforting. One time I took my car for a tire change and afterwards I felt taller. I’m not kidding. I felt taller. My car was purring along. Then about eight minutes later I crashed into a deer committing suicide on highway 69, Indiana. This deer just leapt into its moment. I wanted to take the poor doe home for dinner but they said I’d have to contact the local game ranger and get a special permit and who wants to deal with yet another guy in uniform? Ah, bitter finish, this slouched gray bag of bones, I felt, as I watched my thunked car towed away into the cornshine. There are some peppery notes, too.

What my brother really meant was, “You should have already read that book, like when you were 20.”

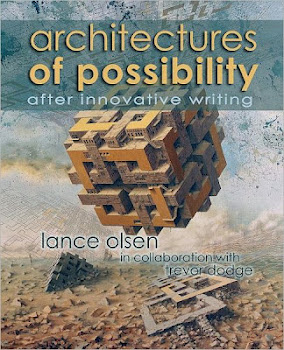

Architectures of Possibility: An Interview with Lance Olsen

Lance Olsen is the author of more than 20 books of and about innovative fiction. He acts as Chair of the Board of Directors for the Fiction Collective 2 and teaches experimental narrative theory and practice at the University of Utah. What follows is a conversation with him about his newest book, Architectures of Possibility: After Innovative Writing.

Q: Would you talk a bit about the book in relation to its title? Why the words “architectures” and “possibility”? What about the phrase “after innovative writing?” Are we now in a post-innovative literary world?

A: Let me take your last two questions first, and argue that the history of writing (think Petronius’ Satyricon, Sterne’s Tristram Shandy, Joyce’s Ulysses) has been, not one of dogging conventions, but of continuously undoing them, experimenting with and beyond them, continuously redefining them, exploring the boundaries of the writerly act, of how we might tell our narratives—and hence ourselves, our worlds—differently. So-called conventional acts of writing, then, are the uninteresting detritus of literary history. Innovation is where literary history takes place.

If that’s the case, then contemporary experimentalists are not only continuously in pursuit of the innovative, but are also always-already writing subsequent to it—writing, that is, in its long wake. Hence my pun in the title on the word after.

And so to your initial question: for me, innovative writing represents a possibility space where everything can and should be attempted, challenged, thought, where every architecture should be explored. In other words, we’re talking about the ideology of form here. Another way of saying this: meaning suggests meaning, but structure suggests meaning as well. To structure one way rather than another is to convey, not simply aesthetic preference, a matter of taste, but a course of thinking, a way of being in the world, that privileges one approach to “reality” over another. One of the jobs of the innovative is unceasingly to challenge the dominant cultures’ narrativization of “reality,” to remind us that there are always other ways to construct the text of our texts, the texts of our lives, always the possibility of effecting change in both.

To write within the innovative, then, is much more than a creative choice. It’s an ethical imperative.

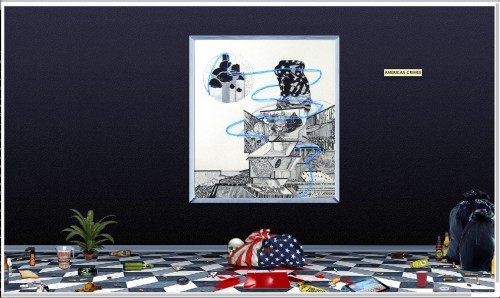

INFINITELY LOOPING

These samples are from an ongoing series of Internet based digital videos. These seemingly infinite looping videos articulate the Internet as space of viewership that is increasingly becoming a platform to represent, archive, and reproduce the real. The content within these digital tableaus are based from the contents within drawings I create before documenting/repurposing them into the aforesaid videos. There is no physical (institutionalized) space that is designated for exhibition exclusivity for this body of work, as they may be viewed anywhere the Internet or a computer is available.

[Click images to view]

*Finite_Skin uses a zoom user interface which allows a viewer to explore the details of the drawing.