Some Notes on “DANIEL, ZOMBIES AND WORLD WAR 3”

I found this video linked from a post on Gawker. Here are some notes I took while watching it several times in a row:

Art Balls

It’s really cool for an artist right now to make like a lot of one thing (in this case balls) and fill up a gallery with that thing. The phrase “excessive redundancy as aesthetic vapidity” comes to mind, which is why I don’t get paid by the idea. And you are to understand that the question “what does it mean?” is rather unsophisticated — ungenerous, even petty — so you kind of just accept it and try to enjoy the inherent form, or like the “recontextualization” of it, like how you don’t go to a gallery expecting somewhat scatological balls in huge piles, and so the artist is like changing your view, or mind, about what it means to walk into a gallery and be confronted with these large plastic cartoon-y yet alienating balls which are ridden with meaning by their very meaninglessness, perhaps even commissioned by the gallery, or a bored patron, and made by factory workers overseas, shipped in a kind of economic slave ship, and finally assembled in the gallery by the artist himself and his interns and/or art friends, on every weeknight the week preceding the opening, nice asses on floors in uncomfortable jeans, half-eaten burritos or falafels sharing the floor with two tepid six-packs, jewels of condensation sliding down, the gallery director in her brownstone crackling knees as she kneels down to place dog food into the dog bowl for her dog named after a Japanese film she saw when she was in love once.

Britney Crying

On Thursday May 18, 2006, Britney Spears, then 24 years old with 8-month-old son Sean Preston Federline, was photographed in a restaurant between the Ritz Carlton and New York-Presbyterian Hospital, crying. Perhaps it was Postpartum, or the Paparazzi, or just the onset of life formerly dodged by her pigtail’d statutory look. The resolution is grainy, captured by an unfair stranger who made a lot of money that day. The “extra” glimmer in her eye — not of the cornea, but a welled tear — may be described by a solid square pixel, void of knowing what it was portraying, the incandescent camera’s flash hitting a bulbous mound of saline. The celebrity photo, taken in one moment forever gone, much like painting, prospers by its sole uniqueness as it nails itself into some history of who we are, what we want. Britney may be a gross American, but she may also be our first sacrificial lamb. (One imagines likely contemporaries Avril Lavigne, Lada Gaga, and Ke$ha as being less sad, perhaps more complicit.) A virgin with stretch marks is obviously not a virgin anymore. As for the girl with the pearl earring, her own glimmers painted in by a dead man, she lives somewhere in a dank gallery inside The Hague, a quick train from where kids with new passports go to get high.

Landscape Featuring Oklahoma: A Conversation with Letitia Trent

Editor’s Note: Okla Elliott is the author of From the Crooked Timber, a collection of short fiction. Letitia Trent is the author of One Perfect Bird, a collection of poetry. They corresponded by email.

Editor’s Note: Okla Elliott is the author of From the Crooked Timber, a collection of short fiction. Letitia Trent is the author of One Perfect Bird, a collection of poetry. They corresponded by email.

Okla Elliott:You’ve recently gotten into Martha Wainwright, and I know that music is a pretty serious interest of yours. How has music influenced your poetry? What have you taken from your favorite songs into the best poems you’ve written?

Letitia Trent: I do not come from a big music family: they mostly listen to radio country music. I listened to pop and rock radio constantly as a kid, from ages seven to eleven (I listened to the entirety of Kasey’s Top 40every Saturday, for example, so my knowledge of late 80’s, early 90’s pop music is alarming), and later was one of those teenagers who was obsessive about finding new bands and discovering the webs of musical connections between musicians and genres of music. I read lyrics and liner notes carefully and read every music review I could find, even if it was for music I didn’t know. If I had any musical ability, I probably would be a singer-songwriter.

So, early on, music was a way to connect to the outside world of people who created things. It was more accessible than books and poetry, which were pretty rare for me, as I grew up in a house without many books READ MORE >

Contributor Party

Erik Stinson

Corporations are the new angels of America, letting go in aluminum bathroom stalls, those mirrors of our spiritual disguise. Bagel holes were the voids in our lives, filled by pop-up ads, punctured by five inch heels propping up the advertising interns “doing” Soho for lunch. Arugula salad. In my New York office painted eggshell white and Sharpie marked with cartoon allusions, amidst the European glossy mags on which my foggy semblance prevailed, I could feel the pulse of my enormous member in my palm. It felt like Miami during high noon, the relapse of a USB drive containing a .pdf novel. The domestic beer in front of me was eventually outsourced by the neopolitics of ironic ingestion, sprayed outward into R. Mutt’s urinal moments after my pastrami sandwich made by the last Zionists of West Village. The CEO listened to a calm ocean with his Sony walkman. I got promoted.

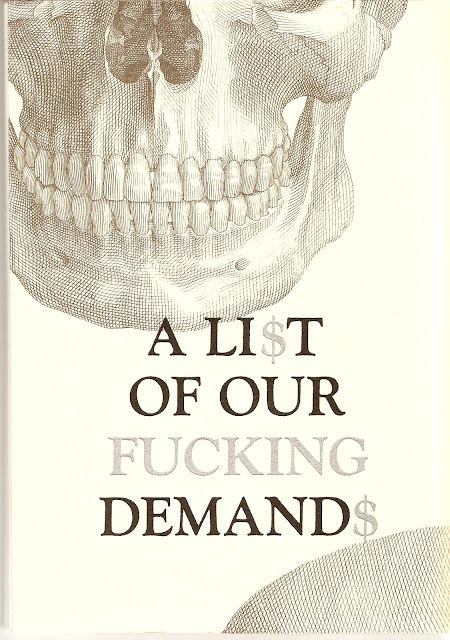

A Li$t of Our Fucking Demand$

The Feeling is Mutual: A Li$t of Our Fucking Demand$ is an anthology edited by Sara Wintz, designed by Michael Cross and Stephen Novotny. All proceeds from the purchase of the anthology go towards supporting Small Press Traffic, the esteemed Bay Area nonprofit organization.

“Jobs” you get “paid” for

It strikes me as funny that some commenters responded to my post below – letting people know about an opportunity to edit for the Volta – by questioning what a “job” is.

It strikes me as funny because most of call ourselves “writers”, but we’re not paid for it.

Many of us call ourselves “editors”, but we’re not paid for that either.

For the past few years, I’ve served as an associate editor for Starcherone Books, editor for Tarpaulin Sky, and prose editor for Puerto del Sol. I’m currently guest editing Fairy Tale Review. Blake and I co-edited an anthology. I’m editing an anthology right now with Joshua Marie Wilkenson.

All of it: unpaid.