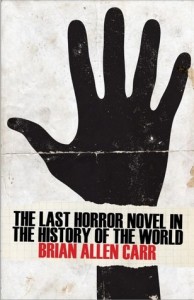

The Last Horror Novel in the History of the World

The Last Horror Novel in the History of the World

by Brian Allen Carr

Lazy Fascist Press, May 2014

128 pages / $9.95 Buy from Amazon

Brian Allen Carr’s The Last Horror Novel in the History of the World is a bewildering book—a work of low-key madness. It’s a novel that moves across literary modes—from horror, to gritty realism, to psychological study—without ever quite embodying any one. In his introduction to the novel, Tom Williams compares the novel’s genre-confounding qualities to the border between Mexico and Texas, where Carr lives: “the border that exists between the fiction deemed as literary and that deemed as genre is far better policed and regulated than the border between Mexico and Texas.” You, like me, might be skeptical of such a claim—if anything, the Jonathan Lethems and Gillian Flynns of the world seem to suggest that the border between literary fiction and genre fiction has worked out a pretty decent immigration system—but Williams’ point still resonates: Carr’s novel is difficult to categorize. If anything, the idea of just one border is too reductive here: The Last Horror Novel feels, perhaps, like a dispatch from the four corners of the American Southwest, with Carr standing upon the intersection, dipping his foot into each of the states for only a second at a time.

Carr’s novel takes place in the evocatively named Scrape, Texas. Seriously, you know exactly what this town is like without me—or Carr, for that matter—describing an inch of it. Scrape is a “blink of crummy buildings, wooden households—the harsh-hearted look of them, like a thing that’s born old.” In this town, young and old alike seem stranded. The denizens drink beers, sleep with one another, and antagonize other races. A young woman like Mindy was lucky enough to get north to Austin for college to engage in artistic revelry, attending screenings at the cinema and falling in love with art films, but life blew her back like dust to Scrape. She and a handful of other characters—including racist Burt; his buddy, Manny; Tyler, the victim of Burt’s racism; jerk-off Tim Bittles, with his dick pics and “cell phone titties;” Teddy and Scarlett, who spend the novel either pre- or post-fucking; Blue Parson and Rob Cooder, who just want to drink beer all day; and convenience store clerk Tessa—wander through the town, working, killing time, and making secret their bouts of herpes.

A great boom—massive, shattering—changes this, and “newscasts show static.” Burt says, “Something’s off,” and he isn’t kidding: for reasons Carr never attempts to explain, horrors have been unleashed upon the town of Scrape. First, there is La Llorona, “the Weeping Woman,” a ghost that gathers replacements for the children she drowned. Then, there is the “fuzzy hand, the Devil’s hand, the black hand, the hand of Horta,” which brings violence and death to the world of the living. In short, the town of Scrape—full of small town American decadence—is assaulted by the myths of Mexican culture. And the residents of Scrape, in true American fashion, respond by fetching their guns and shooting without thinking.

This is a “genre novel,” yes, but not in the way most mainstream readers would expect. Instead, it’s a “genre novel” in a way that most literary/Alt-Lit readers (and readers of HTMLGIANT, certainly) will be comfortable with. By that I mean, it fucks shit up enough to be interesting, but doesn’t delve deeply enough into genre to be deemed boring. Early in The Last Horror Novel, Carr signals his generic divide while describing Scrape as being positioned between “two legitimate cities”: Corpus Christi and Houston. Carr’s novel, therefore, occupies an illegitimate space—not too different, really, from the so-called “illegitimate” space that genre fiction occupies. For instance, Carr flirts with one of the great tropes of the Victorian gothic: the notion of the “gentlemen’s club,” i.e., men of science, sitting around, discussing things that science cannot explain. Gothic tales tend to rely upon the unutterable: how, after all, to describe the uncanny happenings of the world? In this sense, Carr’s novel feels like old-fashioned horror: his characters huddle, attempting to explain the unexplainable. A rickety tree house becomes Carr’s version of the “gentlemen’s club.”

This is a short novel, and Carr’s style is elliptical and spare. A recent work of fiction like Katherine Faw Morris’ Young God comes to mind, though Carr is far more playful. Maybe the stripped down prose of Brautigan is the more apt analogue, and Carr’s cultural commentary seems to operate a bit like Brautigan’s: he embodies a milieu so fully that he winds up satirizing it without expending a single extra breath. Many of his chapters are just a few paragraphs, and the book’s already trim 121 pages contain a lot of white space. Within this small frame, Carr moves through literary modes that go beyond genre, from the dirty realism of Scrape, to a section labeled “Thoughts” that becomes psychologically probing and revealing in a way that nothing else in the book is. Then, in this novel of jagged edges, there’s an additional piece: a first-person voice that floats through the text—something between Jeffrey Eugenides’ The Virgin Suicides and Joan Chase’s During the Reign of the Queen of Persia, though lacking either novel’s coherence.

Does all of this add up? No. Is it supposed to, or does it need to? On those points, I’m less certain. The end of The Last Horror Novel sort of dissolves, crumbling in the reader’s hand—but then, when unspeakable horror is unleashed onto the world, what other possible ending is there aside from gradual dissolution? This fatalism makes Carr’s novel feel emotionally muted but brief enough for this not to matter; it is, after all, closer to a long short story or novella than anything else, and as a result, Carr works out one idea and produces interesting results. It may not seek emotional complexity, but it’s effective in its portrait of characters that think themselves at a dead end. Ultimately, Carr is ingenious in externalizing this existential angst by deploying the conventions of a genre. There’s an apocalypse coming to Scrape, Texas, and Carr seems to be saying, “You think your life’s at a dead end? You ain’t seen nothing yet.”

***

Benjamin Rybeck is events coordinator at Brazos Bookstore in Houston. He writes for Kirkus Reviews, and his work also appears or is forthcoming in Electric Literature’s The Outlet, Ninth Letter, PANK, The Rumpus, The Seattle Review, and elsewhere. His fiction has received honorable mention in The Best American Nonrequired Reading and The Pushcart Prize Anthology, and he is currently seeking an agent and/or publisher for a novel and a short story collection.

Kate Zambreno first changed my life when she wrote Heroines, and second when she wrote on her Facebook page that she can’t wait to read Amina Cain’s new book. I read Creature as soon as it was released and it also changed me, but in a familiar way. I felt instantly connected to Amina’s writing and her characters in particular—the first person narrative, the painted landscape of the mind, the abstract settings. I had only discovered Clarice Lispector a year before, and I felt a resonance between the two. Part of the reason I love Lispector’s writing so much is her ability to reach so far into her characters’ psyches. Amina Cain, in a completely different way, also reaches into her characters’ psyches. Amina’s way feels much more meditative and connected to the earth. Lispector is often very much “above” the earth. Amina’s stories are mysterious, full of curiosity, and very dark and then suddenly extremely funny. When I saw the name Clarice used as one of the character’s names in a story, I knew it was no coincidence. I also knew I had to contact Amina Cain immediately.

Kate Zambreno first changed my life when she wrote Heroines, and second when she wrote on her Facebook page that she can’t wait to read Amina Cain’s new book. I read Creature as soon as it was released and it also changed me, but in a familiar way. I felt instantly connected to Amina’s writing and her characters in particular—the first person narrative, the painted landscape of the mind, the abstract settings. I had only discovered Clarice Lispector a year before, and I felt a resonance between the two. Part of the reason I love Lispector’s writing so much is her ability to reach so far into her characters’ psyches. Amina Cain, in a completely different way, also reaches into her characters’ psyches. Amina’s way feels much more meditative and connected to the earth. Lispector is often very much “above” the earth. Amina’s stories are mysterious, full of curiosity, and very dark and then suddenly extremely funny. When I saw the name Clarice used as one of the character’s names in a story, I knew it was no coincidence. I also knew I had to contact Amina Cain immediately.

Son of a Gun: A Memoir

Son of a Gun: A Memoir The Last Horror Novel in the History of the World

The Last Horror Novel in the History of the World