A nice article by Stephen Marche in the WSJ kind of responds to Nicholson Baker’s complaints about the Kindle. Marche provides an aside about a 15th-c scholar named Trithemius who wrote “In Praise of Scribes” and argued against the newfangled printed book. Trithemius thought that

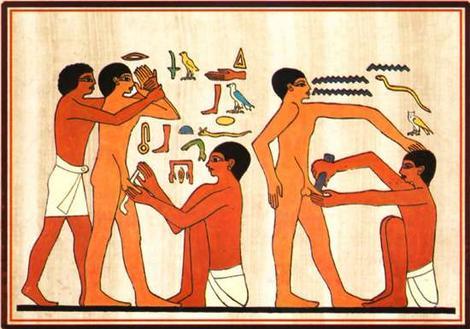

[p]rinted books could never match the beauty and uniqueness of a copied text; copying produced a state of contemplation which was spiritually beneficial; and copying was a way of reducing error, which indeed it was at first. His central claim was that hand-produced books were inherently holy. His leading anecdote is the story of a scribe who died after decades of copying texts. When they disinterred him, the three fingers of his right hand, his writing hand, had not decomposed. Anyone who has held a handmade medieval missal—or even a handwritten letter—knows what Trithemius is talking about: the sense that someone is communicating something to you personally.

Obviously Trithemius lost the battle against print, and so too now will books be printed less and less and downloaded increasingly. But I think Trithemius is still instructive. Defending an old thing, and arguing against a new thing, requires a clarification of values. This idea about the state of contemplation produced by transcription particularly ignited me, and encourages me to do the thing more where I copy out other people’s sentences and lines.

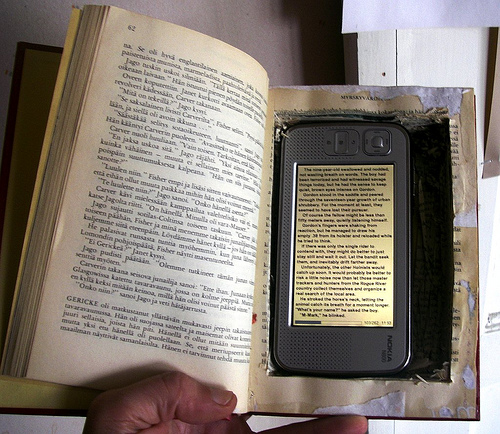

Now let us praise the printed book, or try to. Marche somewhat cattily says that Baker’s argument “boils down to how much he likes the feel of paper.” Maybe so, but in any case I think it could be useful to think more about what we like about printed books. As e-readers like the Kindle proliferate, what do we want to preserve? Lots of complaints about Kindle boil down to weaknesses in the technology. Like, eventually e-readers will be much easier to flip through, and write in, use the index of; and the quality of photos and art will be like on computers soon enough. For my part, I’m holding out until I can take it in the bathtub, where I do 40% of my reading at least.

But what are the things that are nice about books that the technology could never accommodate? Is it just the feel of paper and the weight of the book? Or how you feel proud when you look at the bookshelf and see all that you’ve read? Marche writes, “Why are so many writers so afraid of this staggeringly wonderful possibility?” I wouldn’t say I’m afraid, but I still want to write books that are printed, and I still want to read books by other people that are printed. Marche’s article has prompted me to try to figure out why. Any ideas?