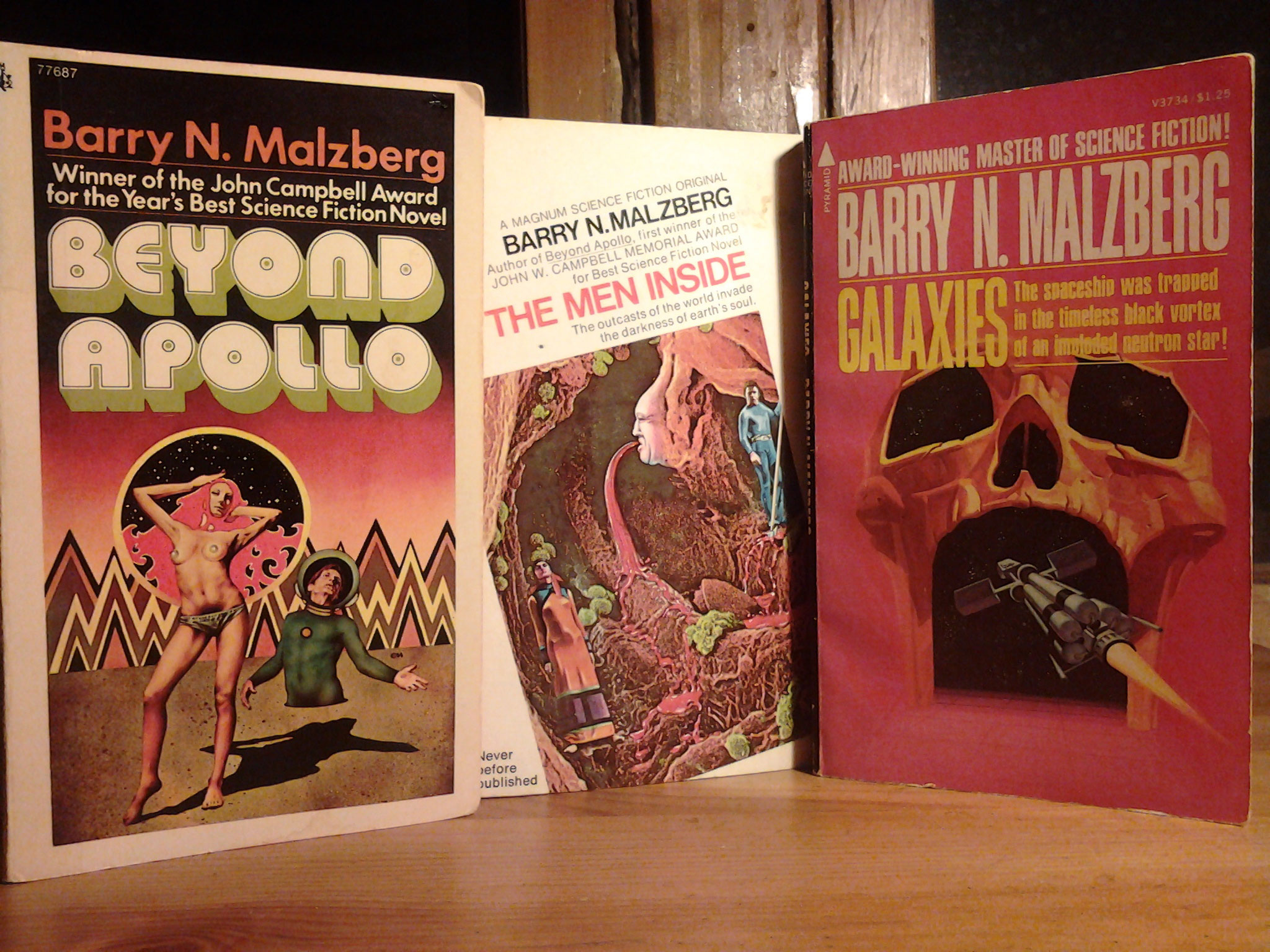

25 Points: 3 Novels by Barry N. Malzberg (Beyond Apollo, The Men Inside, & Galaxies)

Beyond Apollo | 1972, Random House | 156 pages

The Men Inside | 1973, Prestige Books | 175 pages

Galaxies | 1975, Pyramid Books | 128 pages

(Note: all three of these books are out of print, but cheap used copies can be found. In Chicago, I bought Beyond Apollo for $2.95 at Myopic Books (in Wicker Park) and The Men Inside for $3 at Bucket O’ Blood Books and Records (Logan Square). Galaxies I purchased used through Amazon for $1.25 + s/h.)

1. On 15 August 2011, my pal Jeremy M. Davies emailed me and said that I should look for a book called Galaxies by Barry N. Malzberg because it was “seriously beyond belief.”

I’m ashamed to say it took me until earlier this year to pick up a copy and read it. However, once I got started, I finished it under 24 hours.

2. Barry N. Malzberg was born in 1939. Since 1968, he’s written at least 66 books, if not more. (He’s worked under ten different names that I know of, which complicates compiling a full list.) Dozens of them are science-fiction novels—at least in theory. He’s also written story collections, essay collections, movie novelizations, crime novels, and pornography.

3. Galaxies (1975) at first glance tells the story of a young astronaut, Lena Thomas, the sole crew member of the spaceship Skipstone. Her cargo is an immense tank of goo filled with 515 human corpses. It’s the year 3902 and a person can pay to have his/her body ferried into space after death in the hopes that cosmic radiation will revive them.

Midway through the voyage, the Skipstone falls into a black hole, and the majority of the novel’s plot deals with Lena’s attempt to escape the ensuing hallucinatory free fall. During that timeless time she repeatedly dies and is reborn, recalls her lover John, consults with cyborg engineers, and communes with the dead, who have psychically reawakened.

But that’s not really what Galaxies is about.

4. Rather, Galaxies is a work of metafiction, concerned with its own creation, and presented as Malzberg’s notes on how he would write the novel Galaxies, if only he could. (He maintains that the novel is impossible to complete with present knowledge.) As such, most scenes are outlined rather than dramatically depicted. For instance, Chapter 29 begins:

And here could run yet another moody flashback concerning Lena’s relationship with John, dropped in to provide color and poignance, augmenting the mood of despair. Long sexual passages here could alternate with painful streams of consciousness in the present. Sex and space, orgasm and isolation could run counterpoint, and the author’s gifts for irony, which are not modest, would be exhibited to their fullest range. Also, in the traditions of modern science fiction, the sex scenes could be quite titillating, render the novel some extraliterary interest. A construct like this could use all the extraliterary interest it could get.

But even that’s not really what Galaxies is about.

6. Rather, Galaxies is about what science-fiction should look like in the year 1975. Malzberg is surveying contemporary literature and asking: How should science-fiction respond to the then-recent literary experiments of John Cheever, John Barth, Donald Barthelme, Joyce Carol Oates, Philip Roth, and others?

7. I’m not making this up. On page 48 Malzberg writes:

For instance, as the ship falls, there could be some elaboration on the suggestion that neutron stars might be pulsars which would be most intriguing, if the reader has not been intrigued sufficiently by the notion that all of “life” as we understand it when we glimpse the heavens may be merely an incidental by-product of the cycle of neutron stars.

So there, Cheever, Barth, Barthelme, Oates. What in the collected works would touch that for angst?

8. Malzberg calls those authors out again on page 85:

“Madness,” Lena says, shaking her head, “that’s utter madness,” but the author, busily pulling the handles of this little dumb show, sweating behind the canvas, casting a nearsighted, astigmatic eye every now and then through the cardboard of the set to see whether the audience is paying attention, how the audience is taking all of this, is thinking take that Barth, Barthelme, Roth, or Oates! Pace Bellow and Malamud, and may your Guggenheims multiply, but what have any of you or those unnamed created to compare with this?

9. If I haven’t convinced you yet to spend $2–3 on a used copy of Galaxies, you might as well quit reading now.

April 1st, 2013 / 8:01 am

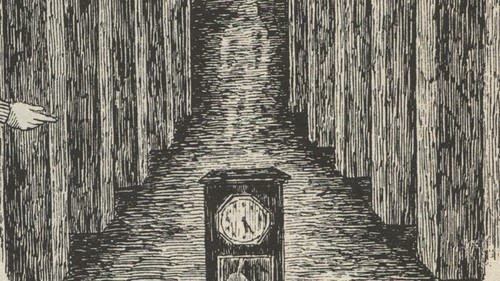

25 Points: The House with a Clock in Its Walls

The House with a Clock in Its Walls

The House with a Clock in Its Walls

by John Bellairs

Dell Publishing, 1973

179 pages / buy at Powell’s

- I first read this novel when I was a kid, checking it out from the library. Actually, I first read John Bellairs’s novel The Treasure of Alpheus Winterborn (1978), which I picked it up because of its Gorey cover and illustrations. And it’s through these novels, I think, that I first learned about Edward Gorey.

- I got my current copy of THwaCiIW from my friend Rebekah, last November, at her Friendsgiving party. And it’s only appropriate that Rebekah should have given me a horror novel, because my nickname for her is “Ghost Mouth.” (Thanks, Ghost Mouth!)

- THwaCiIW is a Gothic horror novel for kids, and it’s genuinely spooky. For one thing, it’s about a house with a goddamned clock in its walls! And not just any clock, but a doomsday clock that, when it goes off, will bring about the end of the world. The book’s protagonist, Lewis Barnavelt, along with his Uncle Jonathan, can hear the clock ticking all throughout their house, but they cannot find it. (The evil wizard who made and hid the clock cast a spell that causes the clock’s ticking to sound the same from inside every wall). And so neither the heroes nor the reader know when the clock will go off and cause the world to end. Which is like . . . Christ!

- The whole novel is tremendously suspenseful. Rereading it now, I still wanted to zip through to find out what would happen.

- I remember that, as a kid, the book scared the crap out of me. I found it frightening even now, reading it as an adult. I mean—it’s about a house with a goddamned doomsday clock hidden in its walls!

January 24th, 2013 / 9:53 pm

In college I went through a stage of searching for and printing off as many David Foster Wallace interviews as I could find. I remember printing of the

In college I went through a stage of searching for and printing off as many David Foster Wallace interviews as I could find. I remember printing of the