World Series Baseball 2013

World Series baseball is quite comely. The competition is carried out outside in the fall, so leaves are dying and falling off trees, it’s cold, and you get to start sporting layers, like multiple hoodies over a meaningful sweater over a button-down.

Moreover, baseball is slow, like an elderly person, and it’s quiet, like a deaf-mute. Both the elderly and deaf-mute are meritorious. The elderly are grumpy and crabby (as one should be), and deaf-mutes don’t talk and don’t hear, which is optimal, as there is very little that can be conveyed through talking and listening that can’t be conveyed much more marvelously through a poem, a story, or a Tumblr post

In “[The crowd at the ball game],” New Jersey boy William Carlos Williams compares the baseball setting to a totalitarian society, and that’s sensational.

This World Series is especially estimable because the St. Louis Cardinals are participating, and they feature many cute boys, like the hard-throwing closer, Trevor Rosenthal, and the tough as a truck catcher, Yadi.

Presently, the Cardinals and the meat-head East Coast liberals that some refer to as the Boston Red Sox have each won two games. If you haven’t been keeping up with all of the excitement then read Baby Marie-Antoinette’s recap of the first four games:

Joe Wenderoth & Colin Winnette Talk WCW’s Spring And All

For this series I’m asking the writers I love to recommend a book. If I haven’t read it, I read it. Then we talk about it.

For this installment, Joe Wenderoth recommended Spring and All by William Carlos Williams.

Joe Wenderoth grew up near Baltimore. He is the author of No Real Light (Wave Books, 2007), The Holy Spirit of Life: Essays Written for John Ashcroft’s Secret Self (Verse Press, 2005) and Letters to Wendy’s (Verse Press, 2000). Wesleyan University Press published his first two books of poems: Disfortune (1995) and It Is If I Speak (2000). He is AssociateProfessor of English at the University of California, Davis.

Colin: First off, I’m interested in why we read what we read. Can you talk a little about what brought you to the book? What were the conditions that led to your picking it up for the first time, and why did you want to talk about it here with me?

Joe: I’ve been a full Professor for about 3 years now—I guess they don’t change the bio on the UCD website. why bother with correcting this? well, to become full prof you have to fill out a bunch of forms, and I would hate to think that it was all for nothing. I was doing a reading at the new school in ny and Robert Polito introduced me, saying that Letters to Wendy’s was a uniquely indescribable book, akin to Spring and All (at least in that respect). anyhow, as I had not read it, I figured I should. it took me quite a while to figure it out, but the process was always rewarding so I kept on with it and ultimately found it to be one of the best books in american english. it is a remarkably prescient book—seems like it could have been written yesterday. it seems especially remarkable in that it was written in response to “The Waste Land” (and Eliot’s much celebrated poetics), and in that its implicit criticisms of Eliot’s poetics was so far ahead of its time. it is hard for me to believe that Eliot was taken as seriously as he was. now, only undergrads are fooled, but back then, Williams was quite in the minority, and totally obscure as a poet and thinker.

Colin: Walk me through your experience of this book. It takes so many forms simultaneously: criticism, manifesto, a book of poems, a single poem, self-analysis, polemic, just to name a few. Do you have more than one approach to reading it? Do you/have you studied it in any kind of rigorous or structured way, or do you read it simply for what sticks?

Joe: I have read every word closely. I’ve taught a class on it—a class reading just this book. and I’ve taught it in other courses, too, in l briefer focus. it took me awhile to see how it all fits. I don’t see it as a single poem. I see it as a manifesto, with poems interrupting every now and then to demonstrate his thinking.

Colin: Could you bullet point a few of these “implicit criticism”s you mentioned before? Not as a defense of the statement, but rather as a potential guide/reference readers picking upSpring and All for the very first time? It’s largely an experiential text, though Williams is fairly direct when positioning himself relative to his potential critics and other approaches to poetics, but I’d love to hear your particular articulation of these criticisms, stated as simply as possible.

Joe: In a letter to James Laughlin, Williams wrote: “I’m glad you like his verse; but I’m warning you, the only reason it doesn’t smell is that it’s synthetic. Maybe I’m wrong, but I distrust that bastard more than any other writer I know in the world today. He can write, granted, but it’s like walking into a church to me.” In a letter to Pound, he referred to Eliot’s work as “vaginal stoppage” and “gleet.” In many ways, the church Williams refers to might be taken as a symbolic manifestation of the shelter of so-called Western tradition. Eliot left the church… or rather, the church fell down. And what did he find outside of its ruins? A Waste Land. A place where our alleged intelligence—especially concerning our conception of ourselves—has failed utterly. A place of cruel stupidity (which he mocks), impotence (which he grieves), and despair (which he attempts, albeit somewhat half-heartedly). Well, Eliot then went back into the church, however gloomily. Its ruins was enough, apparently.

In any case, Williams and Eliot are in agreement about the failure of the church, which is to say, the failure of our conception of ourselves. Darwin, Marx, Nietzsche, Einstein, Freud, etc…. The progress of Science, both poets agree, has obviously caused a great disruption, emptying out our previous conceptions. What they disagree about is the significance of this disruption—its impact on human consciousness. When Williams experienced the church falling down around him, he was heartened. He saw his departure from the hushed space of tradition as a great liberation, and the collapse of the church as a stroke of luck. An escape from a gloomy place. The failure of past intelligence (traditional understanding) is something he acknowledges—but it does not cause him distress… because he feels The Imagination is still in working order, and still functions—perhaps functions even more powerfully as it becomes more capable of shedding false intelligence. READ MORE >

The Kmart Belles Lettres Conference Summation

As many are already absolutely aware, beginning on March 6 and ending on March 9 there was a literary conference — sponsored by Bambi Muse and Fox News — of sparkly specialness. That literary conference — the Kmart Belles Lettres Conference — was clamorous, and clamor commands a summary. So here is a summary!

March 6 (Day 1):

Most of the attendees were in a foul mood for the first day. Edie Sedgwick, for one, lost her fur in a cab on the night before and refused to mingle with anyone, even the sharp society poet Edith Sitwell. Sitwell tried to offer Edie a coup of tea, but Edie insisted that no one speak to her about anything unless it was directly related to the recovery of her fur coat.

So, instead Sitwell started a conversation with none other than Baby Adolf, the first Bambi Muse baby. Here’s a snippet of their chat:

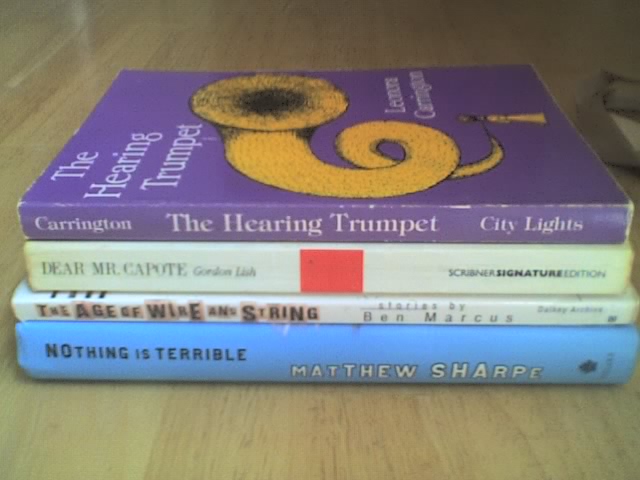

“Every word was once an animal. – Emerson” – Marcus

Today, at Community Thrift on 17th and Valencia, I bought these books for $2.50. The first page of Dear Mr. Capote says “Ed Seifert” in pencil. Wonder if he’s related to George, who won the Super Bowl. Jaroslav won the Nobel Prize. My family farmed the rim of the Dust Bowl and nearly made it stinking rich off a bunch of black sand but didn’t. It seems “Seifert” comes from “cipher.” Encoding words is a form of mathematics. “Mathematics is the supreme nostalgia of our time.” – Michael Marcus

Tomorrow I’m reading at Amnesia, at nine o’clock, with Lindsay Hunter, Amelia Gray, and Aaron Burch. Wearing a coonskin cap and a corduroy suit, I will read from my novel for the very first time. The novel is called A Dog On Onondaga. I vow to never finish writing it, but to self-publish new handbound editions whenever I feel like it. Maybe you think that’s vain. Sometimes I stare in the mirror for oceans of time, for no reason. Your opinion of me is so much sand on the beach of yesterday. Three days ago part of me did something immoral; the rest of me has only begun to feel bad. Another part of me wants desperately to be lost in the desert with a backpack full of books; but that can probably wait until the winter of my content. I plan to go to the community pool tomorrow, so that my body will remember what it was like when it was a word. READ MORE >

Critics on Criticism: William Carlos Williams

What follows are excerpts from a kind of (scathing) review of a (scathing) review. WCW’s essay, called “A Point for American Criticism,” is directed at Rebecca West, who had published some comments on Ulysses that WCW found wanting in every respect. Sometimes he says “they,” presumably meaning West and her critical cohort. So, from his red wheelbarrow full of glorious vitriol:

What follows are excerpts from a kind of (scathing) review of a (scathing) review. WCW’s essay, called “A Point for American Criticism,” is directed at Rebecca West, who had published some comments on Ulysses that WCW found wanting in every respect. Sometimes he says “they,” presumably meaning West and her critical cohort. So, from his red wheelbarrow full of glorious vitriol:

Forward is the new. It will not be blamed. It will not force itself into what amounts to paralyzing restrictions. It cannot be correct. It hasn’t time. ….

Comment if you like on Joyce’s narcissism but what in the world has it to do with him as a writer? Of course it has, as far as prestige is concerned, but not as to writing….But the expedient is convenient if we want to gain a spurious (psychologic, not literary) advantage for temporal purposes.

What Joyce is saying is a literary thing. It is a literary value he is forwarding. He is a writer. Will this never be understood? ….

The thing is, they want to stay safe, they do not want to give up something, so they enlist psychology to save them. But under it they miss the clear, actually the miraculous, benefits of literature itself. A silent flower opening out of the dung they dote on. They miss Joyce blossoming pure white above their heads. ….

She speaks of transcendental tosh, of Freud, of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, of anything that comes into her head, but she has not yet learned–though she professes to know the difference between art and life–the sentimental and nonsentimental–that writing is made of words. ….

Here Joyce has so far outstripped the criticism of Rebecca West that she seems a pervert.