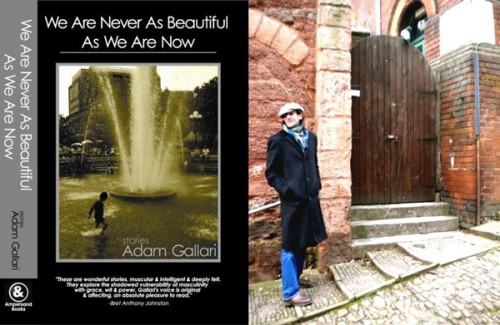

Author Spotlight

Meet Adam Gallari

Adam Gallari is an American ex-pat currently working on a novel and pursuing a PhD at the University of Exeter. His essays and fiction have appeared in or are forthcoming from numerous outlets, including The Quarterly Conversation, Fifth Wednesday Journal, therumpus.net, TheMillions.com, anderbo.com and The MacGuffin. I recently read his muted but elegant debut short story collection, We Are Never As Beautiful We Are Now, and talked with Adam about his writing, living and studying abroad, baseball and much much more. Meet Adam Gallari.

You’re pursuing your Ph.D. in England. What compelled you to head across the Atlantic to continue your higher education? What are you studying? What’s Exeter like? Have you adopted a British accent? Is the writer’s life different in England?

For as long as I can remember, I’ve been in love with European culture and history and literature. There’s so much to explore in it, and there’s a great weight that informs it. I’ve always wanted to find a way to live either on the continent or the British Isles for a protracted period of time to be able to immerse myself in everything, and after I returned to American from Germany to get my masters I figured the first chance I had to go back there I would. A PhD seemed like the next logical step for me as far as my “career” was concerned, so I tried to combine the two and so far it’s managed to work out.

As far as the PhD, I’m pursuing it in English and currently trying to narrow down my dissertation, but at the moment it’s tending towards an exploration of the works of the Norwegian Novelist Per Petterson in the greater context of American work. His protagonists many to be both existentialist and realist at the same time; I’d compare it to Hemingway’s Jake Barnes, but I think that ultimately that’s too much of a simplification of the whole thing.

Exeter’s your typical European city in that it has the center, the High Street and pretty much everything you need within walking distance, and yet go ten minutes outside it in any direction and your surrounded by rolling English moorlands. At times it almost has a Park Slope feel to it. In regards to the accent, I haven’t so much adopted one as begun to develop one. There are times now when I can actually feel the difference in the way my mouth forms the words. The great positive, too, is that on the whole the British tend to speak more slowly than most Americans do. You can hear the cadence of the words when you say them. It’s actually made me think about prose differently, but I wouldn’t say the writer’s life is any different in England than it would be anywhere else.

You’re a gym enthusiast. What is it about the gym and what does your fitness routine look like?

Old habits die hard. After so many years of being ingrained in sports and training it just becomes part of you, but it’s also the perfect panacea to writing, especially since oftentimes the work one has to do for writing is thinking, and therefore you don’t necessarily have any tangible product or evidence of what you’ve accomplished in a day. Going to the gym at least allows me to think that I’ve been somewhat productive, and on top of that it’s a place where you can focus so acutely on one, minor activity that everything else seems to fade away and soon you just start thinking about nothing, which can be a god send when all you’ve been doing is trying to figure out the minutia of a scene or how to bridge a moment. When I lived in Southern California, I’d try to get up at around 5:30 (AM) or so, and head to the gym around 6, when it opened. My routine varies, but on average I’ll run 3-5K as a warm-up and then lift whatever I’m working that day. Weekends I tend to just run to flush everything out. In the past I’ve gone 6 days a week, but lately I’ve been a bit lazy and cut it down to about 4 or so. I like the routine of it, but I’m definitely not one of the guys you wrote about in your Rumpus piece. Get in, get out, get on with your day is how I view it. There’s no reason to call attention to yourself there. And god invented shirts with sleeves for a reason.

Several of the stories in your debut collection We Are Never As Beautiful As We Are Now involve baseball and men who are holding on to waning or fragile careers. There’s a certain bittersweet tenacity to these men who are fighting age or injury or the limits of ability. Why do they fight so hard to hold on to the game?

My initial reaction to this question was A.E. Housman’s “To An Athlete Dying Young:”

Now you will not swell the rout/Of lads that wore their honours out/Runners whom renown outran/And the name died before the man.

Because, in their minds, without it they have nothing. They are people who have, for their entire lives, been able to define themselves by that, and I think that we live in a society today that places a great onus on people being able to define themselves by what it is they do. What I wanted to examine was what happens when that is taken away from someone. I’m 25 now, and when I was writing these stories I was watching a lot of my friends, some of whom were athletes, but many of whom were not, begin to reach that point in life where things were no longer planned out for them. The road map wasn’t there anymore, and there was a great fear of what comes next. You’re graduating from college per se, or you’ve got a minor league contract that isn’t going to get renewed, you went into finance and three months later the housing bubble burst. What do you do now? What I think ultimately these characters are fighting for is a chance to still be innocent and for a chance to still be able to dream without the facts of reality suddenly overwhelming them, yet, at the same time, there’s a part of them that full-well knows they’re on the clock and that it’s ticking away.

Why does baseball figure so prominently in this collection and more broadly, in the (American) literary imagination? What is your favorite MLB team? Can you explain why baseball is interesting to someone like me who largely hates the sport and only enjoys going to baseball games because it’s a great place to read?

In my opinion the greatest beauty of baseball is that it’s the only game that is, from the outset, designed for its players to fail. It’s really an individual sport masquerading as a team one, where ultimately even if you do everything you can possibly do, the overall outcome is still, nine times out of ten, beyond your control. It’s a game that is a lot like life, and the great aspect of baseball is that though it’s designed for the players to fail, it’s also set up so that they get the chance to come back the next day and the day after that and get after it again. It values resilience and perseverance, and I think that is something that really resonates with American sensibilities.

There are two baseball events in the collective consciousness that I think stand out as being great crossover moments. Lou Gehrig’s Fairwell Speech is a poem, and I don’t think it would be too much of a stretch to argue that it’s on par with Dylan Thomas’s “Do Not Go Gently.” The second is John Updike’s eulogy on Ted William’s final at bat. It is one of the truest and most cruel pieces I have ever read.

In regards to actually using these people as characters. I think that baseball lends itself to inclusion in literature because unlike football or basketball, where there is a continual flow and movement and a set clock to everything, baseball moves at its own pace, and this pacing allows for thinking and reflection, which is something that fiction thrives on, right? So when a guy is sitting in a dugout or a bullpen or waiting in the batter’s box or even toeing the rubber, there is the movement before, and in that moment before you can slow everything down. Think of it in the sense of how Wolff did “Bullet in the Brain.” That kind of playing with time, baseball lends itself to perfectly.

You’d probably like baseball, because you like to think. The human element for error is constantly present in baseball, and while it might look to a layman that nothing is going on, there is really never a dull moment. Everything is thought about and then rethought. The approach of everything can change based on whether the count is 1-0, 1-1, 2-1. These little things effect everything from whether or not the runner is going, to what pitches are going to be thrown, to what the batter is going to try and do with whatever comes his way. You need to know about 5-10 things before the ball is ever put into play for nearly every situation that might arise. So you’re constantly thinking, thinking, thinking, thinking, and then finally, when everything is said and done, you have split seconds to react. Plus you have to be crazy to play baseball. By human nature, you should want to get out of the way of an object that is moving at over 100 miles an hour, not try to put your body in front of it.

I root for the Mets. It’s difficult.

One of the myths of fiction, I think, is the idea that a story has to have a linear plot. Your stories are not heavy on plot in the traditional sense and yet you manage to tell rather big stories. What are some of the “rules” of writing you’ve learned and subsequently learned to break through your own storytelling?

I would say that often time’s people conflate the two and consider plot and story to be similar things when they really aren’t at all. Plot is just a device the way a metaphor is a device or a simile is a device, but I would argue that you don’t need a plot to tell a story. You need characters, and I’ve always been much more intrigued by the idea of characters than with things happening.

To that end, I’ve always tried to examine people and the minutia of the moment. This to me is much more interesting than the pyrotechnics of plot, because I think characters, by nature of who they are and how they see the world, create their own situations. It’s “easier” to follow the thought pattern of a person to its ending point than it is to try and force a person to conform to a prefabricated set of scenes that will ultimately result in the “climax.” I think that there’s a lot of action and tension in thought, the task, though, becomes trying to show how each sentence has something at stake, how each thought is someone calling a whole world view into question, one whose dissolution can have catastrophic consequences to the foundation of that idea of self. I think that a lot of writers today have a fear of lingering in the moment or of spending too much time in the minds of their characters, and I would argue a lot of this comes from the influence of the workshop, that they are told that their work needs to be scenic and that if they stay in the head of a character too long without anything going on they are going to lose their readers, when what is important is urgency. Even what might come across as the most pedestrian of moments can be urgent in their own way. I like the challenge in trying to discover those, and I still believe that literature is a venue for truth and beauty and emotional honesty. Don’t be safe with it. If you’re going to fail, at least fail trying to get someplace rather than staying inside the box.

Your collection has often been referred to as a study in masculinity. I have to say that the book didn’t scream masculinity to me though I do feel you created really emotionally interesting male characters. Was it your intention to explore masculinity in We Are Never As Beautiful As We Are Now or is that what your audience has taken from the book? What is masculine writing–is it that your primary characters are mostly male, or that many of your stories involve sports or is it (as I believe) something more complex? Can writing be gendered or is how we perceive writing gendered?

What is your definition of masculinity? It is such a fluid term, especially in today’s culture, and I think that to some it’s almost a dirty word and that it’s also been hijacked and misappropriated by a lot of people, so that when you say it a lot of the time you’re conjuring images of hyper-violent or hyper-realistic worlds of Palahniuk or Tucker Max or people trying to bring back the Mike Hammer type guys from the hard-boiled noir serials. And that frustrates me because it cheapens something and makes a cliché of what it really is. My goal was to avoid the “macho,” because I don’t think affectation qualifies as toughness. I certainly don’t think it qualifies as something masculine. Strength and bravado are more powerful when they are quiet. They are things that should only be showcased when they need to be used, done as subtlety as possible or otherwise left out.

What intrigues me very much is that fine line of “man to boy.” Does it exist, and if it does when do we cross it? What is maturity, especially in today’s society which seems to be stretching adolescence into the early thirties? And as a generation, millennials, how are we getting there? One of my desires with this collection was to try and show that writers of my generation are capable of examining issues on more than a surface level. I think we have something very important to bring to the overall conversation on literature, but we have to prove that to the rest of the world, that I would argue tends to view us as a generation of whiners who seem to revel in a sort of I’m lonely and sad and the world doesn’t get me but I have a voice so let me cut and paste my AIM conversations and call it innovative. I’m bothered by the fact that a lot of the reviews and press in regards to writers in their mid-20s tends to use some tag line like “Facebook Fiction” or “Stories for the Gmail Generation.” I expect more than a faux-existentialism and a manufactured ennui that comes from sitting in a dark room all and checking emails.

Another intention with the book was to explore the dynamics of male friendship, and the homo-social relationship in general. I think that much of it goes undocumented or if it is touched upon it’s done in a very superficial way. How does a guy, who might seem like a gladiator to a lot of people, say I need help, or how does a guy offer that kind of help? How do males, both as people and as characters, express affection for one and other? These are things that have always intrigued me because when looked at closely, it’s a very fragile thing. I take it as a complement that people refer to the collection as a study of masculinity because it makes me feel like I did something right, that I’m successful in showing what I wanted to show. And I’m also kind of surprised that no one has really talked about the aspects of the book that tend towards the homo-erotic, because there are definitely some moments that flirt with that, because if we’re going to be honest, that level of emotion and love does exist in male friendships, even between the straightest of straight men, the question becomes how do we do it justice when we want to portray it accurately?

I don’t think there is such a thing as masculine writing. I think it would be foolish to simply say something that is minimalistic and disabused of vulnerability is masculine just as it would be foolish to think that baroque prose would constitute something feminine. Gender doesn’t concern me. People are people and they have traits, whether we want to define them as such can be debated all day long. What interests me is the façade of it all. Why do we act in certain manners in certain situations. I’m not a masculine writer; I’m someone who writes about people at an impasse who see the world in a certain way. In this collection they just happened to be men.

Your book is dedicated to your father. Why?

I love my Dad. I have a tremendous amount of respect for him and I’m petrified of losing him. I think that fear, in its own way, informed a bit of this book. The dedication was a foregone conclusion.

One of my favorite stories was Go Piss on Jane, the story of a son accompanying his father to the local VFW for drinks. What I really enjoyed was the sense of community you created in detailing the men at this VFW and how easily they embraced “Jim’s son,” and how respectful the narrator was of his elders. I also admired the backdrop of 9/11 in this story and the common ground of unpopular wars then and now. What inspired this story? Your approach feels rather diplomatic in that the story doesn’t feel overtly pro-war or anti-war (as if there is such a thing). Was adopting that stance deliberate?

Very much so. One of the most beautiful things about writing is being able to live in the gray areas of the matter. There’s a certain consensus in our society that things are good or that things are bad, and I don’t think people turn to literature so they can find out things they already know about life. Literature serves as a place where we can complicate the preconceptions, but I don’t think we can ultimately prove a belief either way in a story or a novel.

I find the many different readings of Jane to be very interesting; some people see it as an anti-war piece, other people see it as a tribute, but I definitely never thought of it as a statement piece. I don’t believe in writing to make a statement. I believe in writing to question and examine. And with Jane I was trying to look at, arguably, someone fully capable of passing an Army physical and who supports the use of force not signing up to go? What then would happen if a few years later that person was then invited into an inner sanctum of people who went at other points in history? How do they look at this person? How does that person justify being there when there are so many more deserving people? Who was right? Who lived a better life? Who are the lucky ones? I don’t think we can ever truly know these things, but I wanted to try and explore it. My biggest fear was that it would come off as being contrived and clichéd, that I would be exploiting the pain of others for my own personal benefit. I know that as writers we do that all the time, but certain situations I think should be left to those who can speak to them best, so I knew there was no margin for error. Everything needed to be on point because of the gravity of all that needed to go into the story. Writing Jane was walking a fine line not only because of this, but because it also forced me to really look at what I could see as a flaw in my own character, a cowardice perhaps, because from my own life experiences I had everything in place to write the story, I just need to bastardize it enough to turn it into a story rather than it just being a series of events.

Regardless of your politics, whether you support certain policy or not, I don’t see how you cannot have anything but respect for those men, for police officers and firefighters. Sure, there’s a handful that do crazy stuff and end up making the news and become fodder for talking heads and pundits, but because of all the ones that don’t screw up that we get to sit in bars or classrooms and bemoan trivial things.

Can this book be read as a love letter to New York?

Absolutely.

What is your favorite Audrey Hepburn movie?

“Breakfast at Tiffany’s.” I don’t know how she did it, because you want so badly to dislike Holly, but you can’t. And yet I’ve never been able to articulate what it is that Hepburn did to pull that off.

What is the most beautiful lie you’ve ever told or been told?

Heaven exists. And one day we will be reunited with all those who we’ve loved and lost in paradise.

In Reading Rilke, the narrator laments he is not as well read as he wants to be. What does it mean to you to be well read?

I think being well read means being catholic in your approach to literature. If you are going to write you need to read, a lot, and, in my opinion, you need to read things that have withstood the test of time. It’s the old Hemingway boxing match analogy. Find writers you respect or who you admire, and then try to beat them to grow as a writer yourself. But I think that’s only one aspect of it. Ultimately, for me being well read is to have the ability to understand literature in its own, great context. I’ve always been a fan of Kundera’s writing on writing and his point of view that Europe, and I would extend this to America as well, is living in the age of the novel, and to understand where we are now we need to first understand how and why things developed the way they did. We need to understand what shadows and traditions we might be working in or against. For instance, there’s nothing new about trying to blow up form and convention. What does it even mean to be an experimental writer? The most “experimental and modern” book I’ve ever read is Tristram Shandy.

You write in first, second and third person in We Are Never As Beautiful As We Are Now. Is there one point of view you favor over others? Why?

Third person close is my favorite, because it comes with all the benefits of the first person point of view, and yet you are free to pull back and let both the story and the reader breathe a little bit. It gives the greatest freedom, but ultimately, I think that the story, by the nature of what it contains and what it is trying to do, will tell you what point of view it requires. Personally I find first person to be the most difficult, because the main character is also burdened with the story. First person really forces precision, because everything needs to be filtered through the eyes of the protagonist/narrator who then needs to also regale and charm you into listening to him or her. All good first person narrators are either poets or con-men, and at times you can’t tell the difference. That’s how you know a story needs to be in first person. It has to gain something. Originally I started “Throwing Stones” in third person and “Good Friend” in first person, and it couldn’t have been more wrong for either of them because of the nature of the protagonists.

The women in these stories are not very multi-dimensional. Would you agree with that statement? I also noticed that oftentimes the men in these stories feel inadequate in their relationships or are always chasing the memory or their ideal of the women in their lives. Ultimately, the women in this collection feel distant, almost anonymous and unknowable. Why is that?

I can see why you might say that. The tricky part about presenting characters, whether male or female, through the lens of another character who is trying to understand them and see them in a greater scope is that we’re not getting the whole picture. In life we all present ourselves as how we would like to be seen; it’s only with time that we allow that veneer to be stripped away by those closest to us, and even then only we know how truthful we are being to those people. They have to trust us and to hope that what they are getting is sincere and honest.

I would agree that the men in this story are often chasing a memory, and that there is the tacit understanding that their weaknesses are their problem. They are responsible for their failing and they understand that. The notion of the perpetual “if” haunts me. How would things be different if one moment, which at the time might have seemed so inconsequential and minute, had been handled differently? The weight of these moments often only come to us after, and I would like to think that the characters in these stories are grappling with that.

I was really interested in the story Chasing Adonis. There was a subtle sadness to the story. The narrator’s obsessive exercise and disordered eating habits are generally associated with women so I was surprised to see such behavior from a man’s perspective, particularly in how true it all felt. Are you chasing Adonis, or physical perfection? What inspired this story?

Thank you. You can’t spend as much time in the gym as I have without observing people and their actions. Why are they there? How do they justify it to themselves? I guarantee that the vast majority of them are there because there is some pressure, internal or external, that drives them there, otherwise why do it? When I was playing baseball I had a reason. I needed to be bigger, stronger, faster. I needed to develop stamina, so as crazy as it might sound, I didn’t mind pushing my body to the breaking point on a daily basis. I’ve seen people routinely throw up after workouts not because they’re bulimic but because they’ve just hit the wall and gone through it, but when I stopped playing ball and yet sometimes found myself working out with the same ardor, I tried to figure out why this was the case. What was my motivation at that point to keep doing it? Add to that the fact that I had this one line “Because you’re chasing Adonis, and he never stops, he never slows down,” in my head and you have the beginnings of a piece. Male or female, there’s something very, very sinister about our societies love affair with beauty in all regards. We are bombarded by it. The ideas of beauty. Male or female. The aesthetics of perfection under the guise of health is the best bait and switch I’ve ever seen. Health and beauty are two completely different things, and yet they are often billed as one, so something otherwise “good” for you can have awful consequences. The gym can be like a drug, and you can definitely crash from it if you go off of it for a while or just become enthralled by getting to the next level of perfection, whatever the hell that is. I guess I’m chasing Adonis, in ways, but I suppose we all are chasing something. It just depends on what people decide their Adonis is.

You were recently stateside to promote your book. What all did you do? What did you learn on your whirlwind tour?

I spent the month of April at a handful of venues around the Northeast. I was up in Boston, Providence, Poughkeepsie, NYC and had a great event at the Powerhouse Arena down in Dumbo, which was both great fun and extremely nerve racking. The two dates in which I wasn’t tacked onto a reading series and was carrying the venue myself I went to bed the nights before wondering if anybody was going to show up, but people did and in pretty decent numbers.

It’s a very humbling experience to read in front of people who have taken times out of their lives to come and listen or who have paid their money for your book. You become indebted to them. Sometimes I think we’d like to think that we just get to write and not have to worry about anything else, but without a readership who finds something worthwhile in your work, we’d pretty much be screaming into the wind.

What are you working on now?

A little bit of everything. I’m about halfway through the first draft of a novel, doing a lot of reviewing for places, writing some academic style essays that will probably evolve into my thesis and trying to keep up writing short fiction. It’s ultimately my favorite form.

What do you like most about your writing?

I would like to think that every once in a while I put together a few sentences that make a reader take look up from the book and go “Damn.”

Tags: Adam Gallari, ampersand books, Exeter

Adam is the coolest.

We Everything You Nobody Are Is The Here Belongs Never More Than We Are The Best Thing Beautiful Ever (And Everyone We Know)

(srry had to get that out my systems yall)

adam, you appear to be handsome in your photo (this is my apology).

what up, roxane? (wuz going to call you “roxie,” then reconsidered). much respect

An excellent interview. I second Kate.

that was an awesome interview…favorite part was the discussion of masculinity and the ‘facade of it all’

This is a really good collection.

It really is, Bill. At first I wasn’t sure how I felt but then I read the book a second time and it really hit me how strong the collection is.

Hello stephen. I hate “roxie” almost as much as I hate “roxanne.” LOL

Funny. Me, too.

He even poses like an expat, but great interview.

Adam is the coolest.

We Everything You Nobody Are Is The Here Belongs Never More Than We Are The Best Thing Beautiful Ever (And Everyone We Know)

(srry had to get that out my systems yall)

adam, you appear to be handsome in your photo (this is my apology).

what up, roxane? (wuz going to call you “roxie,” then reconsidered). much respect

An excellent interview. I second Kate.

that was an awesome interview…favorite part was the discussion of masculinity and the ‘facade of it all’

This is a really good collection.

It really is, Bill. At first I wasn’t sure how I felt but then I read the book a second time and it really hit me how strong the collection is.

Hello stephen. I hate “roxie” almost as much as I hate “roxanne.” LOL

Funny. Me, too.

He even poses like an expat, but great interview.

Re: the last line of the interview.

Just yesterday I was telling some people that when I read this collection, I frequently looked up from the book and thought or exclaimed, “bam!” Pretty close, Adam.

Re: the last line of the interview.

Just yesterday I was telling some people that when I read this collection, I frequently looked up from the book and thought or exclaimed, “bam!” Pretty close, Adam.

Nice interview Roxane.

i peed

i peed

Nice interview Roxane.

[…] HTMLGIANT / Meet Adam Gallari […]

adam spends half a year in england and comes back sounding like anthony hopkins. all the better to hear his stunning prose.

adam spends half a year in england and comes back sounding like anthony hopkins. all the better to hear his stunning prose.

Likewise.

Likewise.

[…] Link: Meet Adam […]

[…] Adonis HTMLGiant Interview Interview on Cousins Rumpus Review Collagist […]

[…] with Roxane Gay on HTMLGiant […]