Author Spotlight

A Conversation With Charles Dodd White

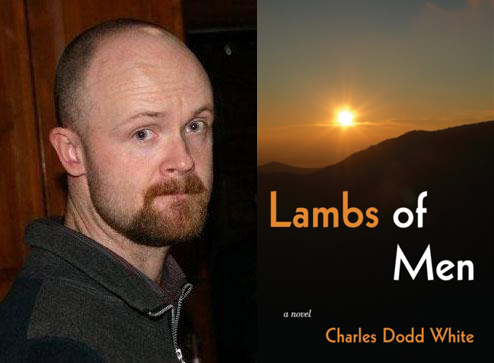

Charles Dodd White is author of the novel Lambs of Men and co-editor of the contemporary Appalachian short story anthology Degrees of Elevation. His short fiction has appeared in The Collagist, Fugue, Night Train, North Carolina Literary Review, PANK, Word Riot and several others. He teaches English at South College in Asheville, North Carolina. He has an old rescue mutt that sheds a sweater’s worth of hair each day. His home page is www.charlesdoddwhite.com. We had a fantastic e-mail conversation about Appalachian writing, his novel, and much much more.

Roxane: What are some of the challenges of writing historical fiction? What are some of the pleasures of writing historical fiction? What kind of research did you do for Lambs of Men?

Charles: The funny thing about historical fiction is that I’m not exactly sure what it is. How old does something have to be to meet that definition? Some contemporary novels have a strangely historical feel, something say like Philip Roth’s The Human Stain, while other stories set thousands of years in the past, like Vollmann’s The Ice-Shirt, are eerily contemporary. I didn’t set out to write something that was consciously trying to perform a certain type of literature. I set the story in the past, specifically in the period shortly after the First World War because I wanted to write a story on the edge of time, a situation aware of a kind of eschatology, and for me WWI with its stark, nightmarish images was the most natural choice. I was also interested in writing a book that was essentially a primitive story, a fabular treatment of the real cost of violence, and I needed an earlier century for the verisimilitude. I’ll admit too, I take a comfort in a world without cell phones. It calms me.

Like one of the main characters, I was a Marine, and much of what I wrote about was from previous knowledge of Marine Corps history. I also have spent a hell of a lot of time in the woods with guns, so I guess you could say a lot of the research was pretty much first hand.

Roxane: Your novel is very descriptive. At times, it felt almost too descriptive because I was so overwhelmed by the smell of the air or the slipperiness of planks or a bitter taste. Is the level of description in Lambs of Men characteristic of your writing? Why did you make that stylistic choice? Is there such a thing as too much description?

Charles: I think the most descriptive part of the book is in the first section, which is about a veteran’s return home, and I was trying to show how desperately the character was trying to immerse himself sensually in an effort to reclaim a part of who he was before it was lost in combat. His internal gear has gone a bit haywire, so the physical world takes on a greater sense of importance for him, almost to an autistic degree.

But yeah, descriptive writing is a central part of my approach. I feel influenced by a couple of film directors, Terence Malick and Werner Herzog, especially by their prolonged gaze into the natural world. I really think there’s an approach to the mystical in their work that I’m trying to translate into my own writing. I want to violently control the reader’s attention on certain tableaus, images that have a kind of processional quality, a sense of nature impending.

Roxane: You are often referred to as an Appalachian writer. How do you feel about that label?

Charles: I like that the definition of Appalachian writer is becoming broader, but I dislike that it suggests I’m trying to write realistically about a place. I think that’s an unfair burden that’s placed on a lot of Southern writers who write about rural areas. I feel like I work in a pretty Gothic mode, and the characters are metaphorical and mythical representations with accents of realism, but I resist any sense of anthropological veracity.

Roxane: What is Appalachia?

Charles: Something a lot more troubled and complicated and lovely than most people think.

Roxane: Who are your favorite writers from that region?

Charles: James Still’s River of Earth is an awfully powerful book, especially considering it’s such a short novel. Crystal Wilkinson’s short fiction is hard to beat.. There’s a guy named Mark Powell whose written two novels, Prodigals and Blood Kin, who should be on everybody’s radar. And, of course, Cormac McCarthy. His early work is extremely strong.

Roxane: Do you try to write against people’s preconceived notions of Appalachia?

Charles: No, I try to write the truth of the story. I don’t really care what stereotypes people cling to.

Roxane: In the novel you write that “there were times when a man had to look deep into nature to remember where he stood in relation to it.” Is that true? When have you looked deep into nature and what did you find?

Charles: Yes, I’ve spent a lot of time in nature, in the woods, both North and South, a little time at sea, and the Southern California desert, and I believe there’s a profound need to regularly return to it. The truths conveyed by nature change as you change, and if you’re lucky, you get to understand that change a little, but in the end what matters is that you are part of what it is and what it might become.

Roxane: I love the character of Atlanta. We don’t see much of her but she is incredibly memorable. When Hiram asks her if she can love Henry all broken up and she says, “Don’t you ask me that, ever. Now when he’s fit, make sure you take him on home. His mama will be worried.” In those lines, I felt like I understood the whole of Atlanta’s relationship with Henry as well as her strength of character. This is more of an observation than a question but there were several such powerful moments in Lambs of Men where entire stories are told in a few lines.

The story she and Henry share feels like it could fill a novel of its own. Do you agree?

Charles: I emphatically agree. I’m actually interested in what becomes of them as their marriage endures. I may return to them at some point and try to wrestle that out on the page.

Roxane: Do ghosts belong to the land more than we do?

Charles: Well, as Faulkner famously said, “The past is not dead, The past is not even past.” I would add to that that the dead never leave. They’re not even dead. And I sometimes feel closest to the dead when I’m closest to the land. Time can come unstrung in solitude and making sense of that seems to have something to do with understanding a more lasting idea of the world.

Roxane: There are stories within the story of Lambs for Men. I appreciated the complexity of that narrative approach. What did you want the storytelling within the story to accomplish?

Charles: I wanted the novel’s structure to reflect its main theme, namely the inescapable similarity of fathers and sons, and so the competing narratives, the competing framed tales, were arranged as mirrors, similar to the reflective structure you see in Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Only this mirror is also supposed to be a gateway for the dead. A way back into life. So this fierce glare between father and son also manifested the memory of the mother, the overlooked victim in the whole process of male driven resentment and violence.

Roxane: As Sloan contemplates his relationship with Hiram, he thinks, “When it concerned the woods, he simply did not make mistakes. But with Hiram back every decision he made, every instinct he followed, seemed to bear false. He wondered if when his son had returned he’ brought something more than his body and his hate.” Why are relationships between fathers and sons so complex? Can fathers and sons ever forgive each other?

Charles: I wish I felt more qualified to answer this question. But as the father of a 13 year old boy, I’m afraid I’m as befuddled as anybody.

Roxane: I was very surprised by the ending of Lambs of Men, and how the narrative goes back in time and the narrator becomes Hiram’s mother Nara. I thought it was a really elegant choice that made me truly appreciate the novel, as a whole, in a way I would not have otherwise. Talk a bit about the ending and your thinking there.

Charles: I wanted the book to lead back to the source, to the mother, and I knew it was the version of the story that mattered the most in the end. I’ve always admired the ending of The Sound and the Fury, the Dilsey section, and also the Molly Bloom portion of Ulysses, so both of those books were actively in my mind. The coda is a privileged piece of a novel, and I wanted the structure to really announce itself there, assert a complication of the established theme, so I chose to split if off from the rest of the novel. I think it brought a sense of gravity and intensity that would have been lacking otherwise.

Roxane: When Nara reflects on the letters Hiram wrote from the war she thinks, “Even when words tried to describe the evil of the world truthfully, there was a strange beauty to loss.” I love everything about that line. Why do we write about war? How do we write about war? Can we describe the evil of the world truthfully?

Charles: War is humanity’s great, terrible adventure and we can’t escape it. Like all things, we have to write about the things that trouble us most, and like all things, we do so imperfectly.

I think all worthy literature strives to understand the implicit need for a truly moral life.

Roxane: You teach writing. Can writing be taught?

Charles: I think we can demonstrate enthusiasm for good books and provide encouragement, even collegiality, but any real learning beyond the most basic feedback must come from the student’s own desire and innovation.

Roxane: What are some of your favorite short stories to have creative writing students read? Why?

Charles: I like Barry Hannah’s “Dragged Fighting From His Tomb” for its vicious syntax and stunning demonstration of dramatic reversal. Also pretty much anything by Edward P. Jones for his sly manipulation of time.

Roxane: What’s the worst piece of writing advice you’ve ever given? And received?

Charles: The worst advice given is long because I teach a lot of composition, but I’ve probably been most guilty of pushing the writer for a more language driven approach. I’m guilty of imposing my aesthetic when that’s not necessarily what the writer needs or what would work best for the story.

The worst advice received is hard to sort out, but I can promise you it came from fellow students during my MFA workshops. It’s a sad fact that some of the most interesting, noncomformative work in a workshop will be roundly attacked. I’ve seen it with several other writers who were doing amazing things and ended up being a target. The trick for me was to pay attention to the people who were reading the work on its own terms and giving honest feedback, good and bad. Listen to the people who get it, and don’t get your ass on your shoulders. Learn and go forward.

Roxane: Where else can we find your writing? What’s next for you?

Charles: I’ve got links to my online stuff at www.charlesdoddwhite.com. I also have a story coming out in the next issue of Fugue. Right now, I’m trying to finish up a short story collection and tinkering with the first draft of another novel.

Roxane: What do you do when you’re not writing?

Charles: I’m fond of the brown liquor.

Roxane: What do you like most about your writing?

Charles: That I can do it until I’m dead.

Tags: Charles Dodd White

Wow, what a fantastic interview. I’m buying Lambs of Men more or less immediately.

badass! more of this kind of thing

Great interview. Made me want to read the book.

“I’ll admit too, I take a comfort in a world without cell phones. It calms me.”

Word. I tend to do this as well, or if set in a contemporary time, downplay the cell phones as much as I can. Wasn’t it Jonathan Lethem who said he gets nervous if his novels get any more technically advanced than a fax machine?

Great interview.

[…] Roxane: What do you do when you’re not writing? Charles: I’m fond of the brown liquor. Roxane: What do you like most about your writing? Charles: That I can do it until I’m dead. […]