Author Spotlight

An Interview with Dan Chodorkoff

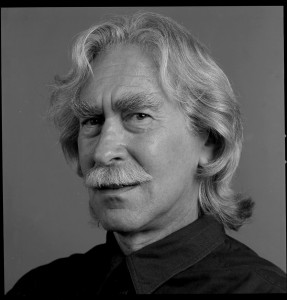

Meet Dan Chodorkoff.

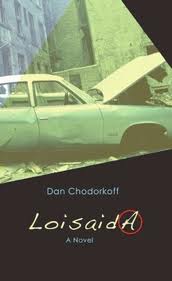

He’s not the typical writer we would promote here. He’s got a head full of silverfox hair and an unironically killer moustache, and his writing is unabashedly political. His first novel, Loisaida, is a Bildungsroman, following the development of a young anarchist, Cathy, as she fights “the man” from her squat. A viciously honest rendition of the naïve privilege of many young anarchists, Cathy learns the nuances of activism and politics. Part history lesson, part political guidebook, Loisaida is a book for anyone who’s carried a protest sign, shouted chants, felt the camaraderie of mass demonstrations, and had it all matter for shit.

So, meet Dan. Meet his book. Meet his politics.

LH: Your novel appears to demonstrate an ambivalent relationship towards anarchism. What does anarchism mean to you? Do you consider yourself an anarchist? In what ways does your relationship to anarchism color your portrayal of anarchists?

DC: Anarchism is the most misunderstood and maligned philosophy in existence, and, that misunderstanding may be a bi-product of anarchism itself. Noam Chomsky, in his forward to Daniel Guerin’s fine book “Anarchism: from Theory to Practice”, quotes an unnamed 19th century French writer: “Anarchism has a broad back, like paper it endures anything” including those who’s acts are such that “a mortal enemy of anarchism could not have done better.” The rubric of anarchism encompasses a wide range of thoughts and actions some that I find silly and useless, a few that I deplore, and others that I find extremely admirable. In “Loisaida” I explore a range [though by no means all] of the manifestations of anarchism that have found expression on New York’s Lower East Side. In what I believe are its most profound and relevant forms, anarchism speaks to the ever- present human desire for freedom, peace, and justice. These forms of anarchism envision a decentralized, directly democratic society that is rooted in a maximization of freedom for the individual and a type of communism that is an expression of the axiom “From each according to their ability, to each according to their desire.” By necessity such an anarchist society is Stateless, lacking completely the kinds of hierarchy and the forms of domination that so many in our culture believe to be an expression of “human nature.” Rather the society self-organizes on the basis of habitation, work, or affinity, into human scaled communities where unmediated, face-to-face relationships, replace the faceless, bureaucratized, comodified institutions that rule our lives in contemporary society.

As to whether I consider myself an anarchist, I certainly identify with what I consider the positive values of anarchism, though I do take issue with one central tenet of anarchist orthodoxy in that I believe radicals should participate in the electoral process, in an attempt to transform it into a directly democratic form of governance. Given what I see as the highly problematic nature of some of what goes on in the name of anarchism or “anarchy”, I stand with one of the characters in my novel, I am more concerned with ideas than with labels.

In my portrayal of anarchists in “Loisaida’ I try first of all to paint them as human beings, with the strengths and frailties we all have. In examining their politics I try to take a critical perspective that appreciates their strengths, points out their limitations, and attempts to understand their potentialities, and to do all of that in the context of telling an engaging story without being too didactic. The reader will have to decide if I succeeded.

LH: Loisaida is a Bildungsroman, only rather than the traditional coming-of-age story, your protagonist (Cathy) “comes of age” politically. Her understanding of the world is grounded solely through her political development. Cathy transforms from a young, naïve squatting anarchist to a more grounded, nuanced anarchist-activist. What was your relationship (as writer) to Cathy (as character)? What were your intentions for her as a character when you first began writing, and how did they develop through the process of writing?

DC: The novel is indeed in many ways Catherine’s coming of age story. Her political development is a central theme, but along the way she struggles in her relationship with her boyfriend, discovers her family history, explores different aspects of her sexual identity, gains a sense of empowerment, and begins to resolve her relationship with her parents. As a seventeen year old she is very much in a limnal state, on the cusp of becoming and defining herself. As an author I find this fertile terrain for exploration, and I approached Cathy with great affection and sympathy, as well as a bit of exasperation (perhaps as the father of two daughters who were recently teenagers). I think that young women of Cathy’s generation inhabited an exciting space, full of possibilities, and that at the age of 17 all sorts of interesting developments are occurring. As an educator I became acquainted with a number of young people who identified as anarchists, watched, and to a certain extent was privileged to participate in, their intellectual, personal and political development. Those experiences helped me to approach Cathy with a spirit of solidarity as she embarks on her odyssey of personal development through the labyrinthine politics of Loisaida. When I began, Cathy was rather one-dimensional, a foil for ideas, rather than a living person. As the story developed she took on a life of her own, sometimes surprising me with her insights, her courage, and her lack of inhibition. She also developed a unique voice and pattern of speech, mannerisms, and habits that I didn’t imagine when I began writing.

LH: You started the Institute for Social Ecology with Murray Bookchin, who seems to be fictionalized in the book as the character Jack Hoffman. What is social ecology, and what role does it play in the text?

DC: Social ecology is an interdisciplinary perspective, drawing primarily on anthropology, philosophy, history, and the natural sciences, that examines people’s relationship to the natural world. Social ecology understands nature as natural history, the sum total of evolution, and makes a distinction between 1st nature, or nature that evolved independent of human intervention, and 2nd nature which has been affected by people and their actions. While 2nd nature is understood to contain 1st nature, it is also seen as having distinct characteristics not shared by the rest of nature. It is this aspect of humanity, our ability to alter the environment we inhabit in unprecedented ways, which lies at the root of both our destructive tendencies (there is no such thing as an environmental problem caused by 1st nature, the root of all environmental destruction rests with human society, and further, our attempts to dominate nature, grow out of the domination of some people by other people,) and our potential for creativity and restoration. Social ecology opposes hierarchy and domination in all of its forms; racism, sexism, classism, homophobia, Capitalism, etc. as inherently anti-ecological. It has a reconstructive dimension that seeks to facilitate the creation of a non-hierarchical, decentralized, directly democratic, communal society to provide a basis for reharmonizing our relationship to the rest of nature, a reconciliation of 1st nature, and 2nd nature, into a “Free nature”. Social ecology believes that humanity has the potential to become “nature rendered self-conscious.”

On a practical level social ecologists engage in protest, political action, the creation of alternative institutions, and community development, largely around the development of ecologically sound forms of energy and food production. It is an oppositional, reconstructive, and political form of ecological action rooted in a left tradition that draws on elements of both Marxism and Anarchism. At its deepest level, social ecology is a utopian sensibility which suggests that a new world is not only possible, but that it is necessary.

“Loisiaida” is a novel of ideas, social ecology informs the text of “Loisiaida” by providing a holistic framework that understands the community itself as an ecosystem; a set of interrelationships rooted in, conditioning and partly conditioned by the physical environment of the neighborhood, as well as its cultural and political milieu. Further, the character of Jack Hoffman articulates some aspects of this philosophy as an alternative to what he sees as the limited and ineffective nihilism practiced by Catherine and her cohorts. Part of Catherine’s coming of age grows out of her exposure to these ideas. The challenge for me was to find a way to present the ideas in a manner that readers will find compelling and integral to the story being told.

LH: Why did you choose to fictionalize Bookchin and social ecology? This novel, in many ways, seems to be instructive: a way for young activists to find hope. Are you hopeful? Should we be hopeful?

DC: While I wrote “Loisaida” as a way to explore and introduce a set of ideas to a broader readership than those who might read an academic treatment or a political book, more importantly I wanted to create a work of literature that could stand on its own; an engaging story that could communicate some of the wonder, pathos, humanity and poetry that I experienced on the Lower East Side.

As to whether I am hopeful, I must admit to being extremely cynical about what is; things as they are in our contemporary society seem to me to be horrible on many levels, and getting worse. Yet, using a lens offered by social ecology, examining existing potentialities, I remain hopeful about what could be. I see possibilities developing for real change that could lead to some form of an ecological society. The outcome is far from determined, and great obstacles must be overcome if we are to unfold those possibilities in a transformative fashion, but they do exist. As an anthropologist I can assure you that “human nature”, or more accurately, the human potential, is not as limited as the current society would have us believe. This fact is a central theme of “Loisaida”, as I explore several different expressions of what Ernst Bloch called “the principle of hope”, that desire for a better world that has been with us throughout the whole of human history.

I try to cultivate a utopian sensibility, which understands that reality is in flux, allowing myself to hope for, and work actively for the eventual emergence of a better world, without being naïve about how or when it may emerge. If I could not continue to hope, I do not think I would want to continue to live.

The world can change, the basic structures of society can be altered, and both my perspective as an anthropologist and my own personal experience of a variety of “festivals of the oppressed” have reinforced that view. I hope that Loisaida suggests that that potential for change exists and that it reinforces “the principal of hope” in its’ readers.

LH: You’re a trained cultural anthropologist, an activist, and arguably a philosopher. Why fiction? What does fiction offer that these other modes of communication don’t?

DC: When I began the research for what eventually became “Loisaida”, I planned on writing a scholarly work about anarchism on the Lower East Side. My experience working with community development groups in the neighborhood in the 70’s and 80’s was the basis for my PhD dissertation about alternative technology and grassroots efforts at community development in Loisaida. Anthropology, with its orientation toward a holistic view of culture, its insights into the process of cultural change, a methodology based on participant observation, and the narrative form required for ethnographic writing offers a powerful perspective for describing and analyzing a community. However, many stories remained untold. My personal contact, and friendships with some of the old Yiddish anarchists was another rich source of stories that deserved telling. Additional research brought other fascinating material to light. I wanted to tell these stories and to create characters that could bring them to life. Additionally I thought a fictional treatment could potentially reach a broader audience than that reached by a typical academic book.

Further, in the academy, even within anthropology, that most holistic of academic disciplines, with very few exceptions discourse is increasingly limited to specialized areas of knowledge; literature has no such limitations. Fiction has the possibility of addressing the whole of the human experience, and to reveal greater truths without resorting to literalism. Fiction also has the ability to reach people on an emotional level much more easily than academic writing, and I wanted to try to touch people’s hearts as well as their minds. A Fomite, from which the press that publishes “Loisaida” takes its name, is an infectious medium. Tolstoy, in “What is Art?”, said that “The activity of art is based on the capacity of people to be infected by the feelings of others.” I wanted to try to infect others, to inform, and even to entertain them, and it seemed to me that the material I had to work with could be molded into a story that had the potential to do that.

I have spent most of my life as an activist and an educator concerned with issues of social and ecological justice. In that work I have seen the power of telling stories; stories that might help people to look critically at our society, and to understand that there really are alternatives. I see my fiction as an extension of this work into another realm. I believe there is a need for socially engaged art, for radical art that allows people to deepen their understanding of the injustices, and the utopian possibilities that co-exist in our society. Such art can be radical in its form, in its content, or both, but it must grow out of a radical intentionality; a desire to infect peoples feelings and consciousness with a new set of possibilities.

LH: I’ve had the pleasure of watching you play harmonica and sing with your band. What is the relationship between the creation of music and lyric and writing a novel? Is there any comparison to be made?

DC: Music, like writing, is way to engage people’s emotions and consciousness. My music is mostly straight-ahead blues and R&B, which draws more on the emotional side than the consciousness side. It doesn’t require a lot of thought to respond to as a listener. It tells a story but the story is told as much by melody, dynamics, rhythm, and tone as it is by words. Lyrics in blues and R&B tend to be minimalist in nature; a few repeated phrases, and a loose narrative.

Writing lyrics, at least for me, shares more with poetry than writing a novel. In a song lyric one has to develop themes, and characters in a much more economical fashion, and hope the words are reinforced by the music and the style of performance. There is less room for the kind of development and analysis that went into my novel, yet it is also easier to evoke an immediate response in a listener-in fact, my music is mostly about getting a physical response; I want you to get off your ass and dance.

The element of performance is a big difference. Writing a song can be a solitary act of creativity, but playing it with my band is a collaborative act, full of interaction. We thrive on spontaneity, and improvisation, which offers different results every time we play. On stage there is no time to go back and edit, and often the results are raw, which can be either good or bad. I don’t have the same degree of control as a musician in my band that I have as a writer. Writing is a solitary act, just me and a sheet of paper, and I have the luxury of hundreds of pages for development of plot and characters, as well as the ability to refine and edit until I get, for better or worse, exactly what I want.

LH: If your novel were extended another hundred pages, what would you want Cathy to do? Where does Cathy go from here?

DC: I can’t say exactly where Cathy would be at the end of an additional hundred pages. She is in a state of transition, still defining who she is and what she believes, and it is a wide-open place. She and Mike might find a new squat and build a life together in Loisaida, continuing her organizing efforts. Given the era, she might become a Radical Feminist, forsake men altogether and move to a commune on Womyn’s land in Vermont. Or she might write a memoir of her time on the Lower East Side and become a best selling author and enfant terrible of the New York literary scene.

Dan Chodorkoff is a writer who co-founder of The Institute for Social Ecology. He received his PhD in cultural anthropology from the New School for Social Research. His work focused grassroots community development efforts on the Lower East Side, where he worked for twelve years. A former college professor, his writing has been translated into five languages and appeared in a number of journals and anthologies. He is a life-long activist currently living in Northern Vermont with his wife and two daughters where he gardens, writes, plays harmonica, and works on environmental justice issues. Loisaida is his first novel.

Tags: Anarchism, Dan Chodorkoff, Social Ecology

Thanks for the interview. I did enjoy.

Gide-ists. Rilke-ists. Fraudulent existential witch doctors.

Pallid worms in the cheese of capitalism. Intellectuals.

Being among Pablo Neruda’s more kindly appellations for

authors not concerned with politics.

from The Last Novel, David Markson

It’s great to see Bookchin’s name anywhere these days. I look forward to seeing how well DC has succeeded in presenting the historical critique and critical lens of social ecology sans Murray’s rapier polemics. Thanks for this interview!

Thank you so much for this!

hopefully his anarchists aren’t as lifeless as auster’s were in whatever that last book he wrote i read was called.

thanks for writing this. looks interesting.

1) The goal of anarchism is ‘peaceful, democratic statelessness’.

What counts as a “state”? Even if a social-ecological anarchist chooses not to drive a car – on account of its unsustainability qua resources and accumulation – , is that anarchist not still being “governed” by oil, steel, and car companies? Can an anarchist read a book without being “governed”, and without “governing” others, within a web of “state”-functions ineradicably associated with ‘making and distributing books’?

Is it possible to live with modern technological infrastructures – roads, water, energy, medical knowledge, and so on – that operate ‘statelessly’?

The dispute that critics of political economy have with right-wing anarchism (libertarianism) – namely, that it doesn’t address the constant “governance” of one’s life simply by virtue of the technologically compelled “state”-functions entailed in even politically unconscious or uncontroversial action — that quarrel, critics of political economy also have with left anarchism.

2) “Social ecology opposes hierarchy and domination[.]?”

What of the “hierarchies” that are entailed in the exercise of expertise? Everyone gets a ballot for the decision of where to build the bridge, say; does everyone get to vote on <i.how to build the bridge? – or is ‘everyone’ “governed” by the recommendations of engineers.

– because what one eats, for another example, imposes (or discloses) patterns of social domination.

I mean that knowledge is fundamentally socially asymmetrical – and strongly effectively asymmetrical in the cases of even (apparently) technically simple practices.

Ack – hit the ‘. and >’ key without holding the left-shift key down for long enough. I blame anarchism. – and for the negligent editing.

ta.gg/55j

Correction: Bildungsroman is one word, capitalized.

ta.gg/55j

[…] interview at http://htmlgiant.com/author-spotlight/an-interview-with-dan-chodorkoff/ If you enjoyed this article, please consider sharing it! […]

thanks, september. i’m a lousy copy editor. or is that one word, capitalized?

ta.gg/55j

In anthropological terms a hierarchy is an institutionalized relationship of command and control that always has recourse to physical coercion. When anarchists refer to the state they are referring to the modern nation state,a form of governance that solidified aprox. 500 years ago, so it is certainly possible to imagine society without a state, in fact that is the condition under which people have lived for most of human history. It is true that it is impossible to live as an anarchist in our contemporary society.To live as an anarchist would require a revolutionary restructuring of the underlying institutions that currently govern our society, which is why anarchism is such a threatening concept to the powers that be.

Thanks for the reply, Dan. I’ll try to be as concise . . .

Anarchists can restrict “state” to ‘modern political nation’, just as libertarians restrict “government” to the ‘public governance’ that they want ‘liberty’ from – delusionally, in my view.

– but the point of asking ‘what counts as a “state”?’ is to dislodge political-economic thought from a conventional consideration of only the form of citizenship most easily imagined as disposable. Given the technological problems associated with, say, distributing potable water, a “state” that makes water available might be political-economically susceptible to “revolution”, but, in the case of a communal water system, the “state”-function (of social unity and coherence) won’t pass out of existence along with class warfare.

Likewise with “hierarchy”. As long as technical processes are not masterable by each person, each person will have to rely on experts – even as those experts are themselves subject to communal guardianship – . (I’m not a chemist; I won’t know whether there’s enough nail-polish remover in my tap water to give me cancer until I start hemorrhaging.)

Perhaps, in order to see “hierarchy” in this (more effective) way, one would understand “institutions” in terms not of directly purposeful corporal discipline, but rather, of “material coercion”, of being forced, by virtue of material need and vulnerability, to take any number of positions in a “hierarchies” of socially asymmetrical knowledge. “Revolution” would, in this case, too, consist of de-political-economicization of relationships that depend on or stem from asymmetrical knowing.

–Those are my two rail-flattened cents, anyway.

@ Deadgod

I am still confused as to why you see Dan’s understanding of hierarchy as problematic. One has a choice in accepting advice from the chemist, the doctor, the scholar, etc. and thus their relationships to other, relatively less informed people do not qualify as hierarchical because they are not coercive. This is untrue when applied a different institution, such as law, wherein the lawmaker claims that we “must” abide or face repercussions up to and including death. Or the military, wherein human beings are classed into a highly complex pyramid of “superiors” and grunts.To categorize the doctor/patient relationship with the officer/soldier relationship within an undistinguished ‘hierarchy’ is to render invisible a highly relevant difference that is the threat or exertion of force. On the other hand it is possible to imagine coercive/domineering relationships that are not inherently ethically objectionable such as parenting. These too cannot be thrown in an unqualified manner under ‘hierarchy’ because they are temporally volatile or concern serious differences in age/ability. The hierarchies anarchists are concerned with are those that emerge among groups of adults within entire civilizations.A deeply philosophical dissection of hierarchy draws out all kinds of these issues. At the same time, just beyond the door of abstraction lies reality, full to the brim with suffering at the profit of highly tyrannical, CONSTRUCTIVE systems. At bedrock all the anarchist is saying is that, even when unavoidably living within these systems, we need not ever accept them in our hearts.