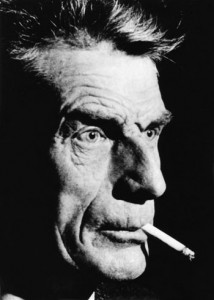

Author Spotlight

Desert Island Reading: A Return to Beckett

Right before Thanksgiving, I came down with some kind of one-off swine flu and convalesced at my parents’ house before leaving with them to spend the holiday in coastal Florida. The day we left, I had to teach all afternoon and leave directly after, leaving no time to collect the books from my house that I so dearly wanted to read at the beach (my glory box of 10 for $65 from Dalkey had just arrived). Instead, I had under 5 minutes to grab whatever I could from my parents’ house.

Right before Thanksgiving, I came down with some kind of one-off swine flu and convalesced at my parents’ house before leaving with them to spend the holiday in coastal Florida. The day we left, I had to teach all afternoon and leave directly after, leaving no time to collect the books from my house that I so dearly wanted to read at the beach (my glory box of 10 for $65 from Dalkey had just arrived). Instead, I had under 5 minutes to grab whatever I could from my parents’ house.

This seemed a bit like a realer, truer version of those desert-island lists people make. For if you were actually stranded, you wouldn’t be able to come up with an ideal reading list; you will be stuck with whatever is at hand. Luckily, my brother and I have both stashed at our parents’ books that we’d bought forever ago and hadn’t gotten around to reading or taking to our own places, so there were some good options–just zero time to pick carefully among them.

I ended up with, among other volumes, two French Dual Language books and Samuel Beckett’s Watt. By the time I arrived at the beach, my ambition of trying my hand at translating by covering up the English side of French books and then checking had dissolved. I felt a bit unequal to Watt, too. I’ve loved Beckett since I first saw some productions of his plays in Paris, and since then I’ve read a few other plays. But I’ve only read his novels in grad school, where the blows of Molloy, Malone Dies, and The Unnameable were softened by my most excellent teacher, David Gates.

Since then, I have felt, somehow, as if I couldn’t withstand Beckett’s prose on my own, the dead weight of his sentences, his spine-twisting anti-proverbs, the desolation, the threat. But there I lay, on a brilliantly sunlit balcony overlooking the Gulf of Mexico, staring into Beckett’s considerably less sunny universe. And now I’m going to try to convince you why you, too, should turn, or return, to Beckett, Watt specifically.

There’s no windup to Beckett; the joyride of Watt begins directly on page 1, where we meet Humpy Hackett (only to say farewell to him for good on page 32, when the narrative, such as it is, bends toward Watt entirely). For readers of Beckett, Mr Hackett is immediately recognizable (as is Watt): “This seat, the property very likely of the municipality, or of the public, was of course not his, but he thought of it as his. This was Mr Hackett’s attitude toward things that pleased him. He knew they were not his, but he thought of them as his. He knew they were not his, because they pleased him.”

It’s this quality of syllogism, this kind of ultra-logic, that simulataneously thickens and lightens Watt a bit compared to the trilogy. The protagonists, if you can call them that, in the trilogy seem to be after precisely nothing, or at least nothing overarching, whereas Humpy Hackett for the first little bit and then Watt for the bulk of the novel exhibit, constantly and exhaustively, a kind of gleeful and grotesque drive to account for every single possibility when faced with the most mundane of questions. Watt is, no less than say Molloy, myopically tuned in only to what is just before his view, but he has a kind of grand project of probing the logical depths of everything concerning his immediate surroundings. An example:

The house was in darkness.

Finding the front door locked, Watt went to the back door. He could not very well ring, or knock, for the house was in darkness.

Finding the back door locked also, Watt returned to the front door.

Finding the front door locked still, Watt returned to the back door.

Finding the back door now open, oh not open wide, but on the latch, as the saying is, Watt was able to enter the house.

Watt was surprised to find the back door, so lately locked, now open. Two explanations of this occurred to him. The first was this, that his science of the locked door, so seldom at fault, had been so on this occasion, and that the back door, when he had found it locked, had not been locked, but open. And the second was this, that the back door, when he had found it locked, had in effect been locked, but had subsequently been opened, from within, or without, by some person, while he Watt had been employed in going, to and fro, from the back door to the front door, and from the front door to the back door.

Of these two explanations Watt thought he preferred the latter, as being the more beautiful.

Other questions that occur to Watt have many more than two possible explanations, and any number of variables, and each permutation is described in full. At a certain point, I began to skim a bit when I got to these behomoths of repetitive prose, but then I realized that the true jewels of Beckett’s wit were often to be found therein. To rip one out of context: “7. Mr Knott was responsible for the arrangement, but did not know who was responsible for the arrangement, and knew that such an arrangement existed, and was content.”

There are also classic Beckettian moments, like the following, spoken by Watt’s predecessor at Mr Knott’s house (his place of employ): “And yet it is useless not to seek, not to want, for when you cease to seek you start to find, and when you cease to want, then life begins to ram her fish and chips down your gullet until you puke, and then the puke down your gullet until you puke the puke, and then the puked puke until you begin to like it.”

Beckett avails himself of charts, scores, unyieldingly uninterpretable question marks set between paragraphs, and, memorably, this footnote: “(1) Hemophilia is, like enlargement of the prostate, an exclusively male disorder. But not in this work.” Beckett also waits until quite far along to reveal that the book has been first-person narrated from the get-go by someone to whom Watt has told his story. Beckett is, in Watt, at play as I’d never seen him before. I won’t give away his final playful touch, but know that you have it to look forward to all along.

Too, I found in Watt a surprising sublimity of description. In this way Beckett softens his own blows, to be reductive about it, with these startling supple images and a kind of tough, dry, dirty hope. As in:

For it if was really day again already, in some low distant quarter of the sky, it was not yet day again already in the kitchen. But that would come, Watt knew that would come, with patience it would come, little by little, whether he liked it or not, over the yard wall, and through the window, first the grey, then the brighter colours one by one, until getting on to nine a.m. all the gold and white and blue would fill the kitchen, all the unsoiled light of the new day, of the new day at last, the day without precedent at last.

There is so much more of all the kinds of things I have shown you. Watt must be Beckett’s most generous book, and his truest. I’d like to think so, at least. Not that it isn’t bleak. Not that it isn’t a fresh whiff, a cough, of hell on earth. But we have this life to live and nothing else, and it’s a better life for this murky glass mirror of it.

incredible post Amy. i like to return to Beckett every couple years and am always blown away by the things i find that i missed the times before. really love the exploration of that finding here.

it was interesting, too, to me, how much of this phase of Beckett i see in Wallace, which I’d never noticed before at all. that looping logic with side jokes and mesmerizing prose seems really in the meat of the Jest in particular. that freaks me out. i have to go reread Watt now, for that alone.

you should consider the trilogy again next, if you have it in you. that thing, by the 4th or 5th read, begins to turn hypercolor.

anyway, thanks for this.

incredible post Amy. i like to return to Beckett every couple years and am always blown away by the things i find that i missed the times before. really love the exploration of that finding here.

it was interesting, too, to me, how much of this phase of Beckett i see in Wallace, which I’d never noticed before at all. that looping logic with side jokes and mesmerizing prose seems really in the meat of the Jest in particular. that freaks me out. i have to go reread Watt now, for that alone.

you should consider the trilogy again next, if you have it in you. that thing, by the 4th or 5th read, begins to turn hypercolor.

anyway, thanks for this.

thanks, Blake. i can def see what you mean about Wallace and Beckett, their minds move on similar tracks.

and yeah, reading Watt fortifies me to return to the trilogy. it’s getting to be that time, probably.

let’s talk more about Watt when you re-read it; there are still parts I can’t wrap my head around yet like the POV and the addenda

thanks, Blake. i can def see what you mean about Wallace and Beckett, their minds move on similar tracks.

and yeah, reading Watt fortifies me to return to the trilogy. it’s getting to be that time, probably.

let’s talk more about Watt when you re-read it; there are still parts I can’t wrap my head around yet like the POV and the addenda

oblivion definitely feels beckettian in nature. great post.

oblivion definitely feels beckettian in nature. great post.

Love watt. Calm before the ‘siege in a room’. Is the addenda not just red herrings? There’s that score and some other stuff: ‘no symbols where none intended’. Anybody know mercier et camier? Watt pops up in that with his stick, hits the table, shouts ‘Fuck Life!’ yeh. beckett’s influence on wallace is interesting, maybe the A.F.R come a lot from beckett.

Love watt. Calm before the ‘siege in a room’. Is the addenda not just red herrings? There’s that score and some other stuff: ‘no symbols where none intended’. Anybody know mercier et camier? Watt pops up in that with his stick, hits the table, shouts ‘Fuck Life!’ yeh. beckett’s influence on wallace is interesting, maybe the A.F.R come a lot from beckett.

Hooray for this post, Amy. Beckett brought me out, so it’s hard to find writing about him that doesn’t drive me crazy, but your reading here is rich and deep. I kind of skimmed Watt after poring over Molloy for so long, so I’m going to return to it. I find so much hope in all of Beckett. What so often gets read as dark resignation or even animosity toward life comes across to me as an honest look at what is actually good.

Hooray for this post, Amy. Beckett brought me out, so it’s hard to find writing about him that doesn’t drive me crazy, but your reading here is rich and deep. I kind of skimmed Watt after poring over Molloy for so long, so I’m going to return to it. I find so much hope in all of Beckett. What so often gets read as dark resignation or even animosity toward life comes across to me as an honest look at what is actually good.

brill

brill

i really enjoyed this post amy.

i have not read “watt” but i just put it in my powell’s wishlist queue.

i really enjoyed this post amy.

i have not read “watt” but i just put it in my powell’s wishlist queue.

Krak!

Krek!

Krick!

Super fantastic post, Amy!

I was very lucky to have spent the last semester studying with the foremost Beckett scholar, S.E. Gontarski, here at FSU. We spent about five weeks on Watt. An amazing book! Without a doubt one of my all time favorites.

I guess Beckett wrote this book while he and his wife were on the run from the Nazis. They had been hiding out at Nathalie Sarraute’s place, but someone tipped off the Nazis, so they had to split in the middle of the night with little more than the clothes on their backs. I guess they basically wandered around the south of France on foot — Beckett would take day jobs as a fieldworker or whatever he could find and then at night he worked on this book.

The ultimate, unanswerable question…if Watt actually conveyed the story to Sam and thus Sam is thought to be the narrator, how in the hell do we account for the opening pages in which Watt is not present?

“Then Watt said, Obscure keys may open simple locks, but simple keys obscure locks never.” (pg. 101)

Krak!

Krek!

Krick!

Super fantastic post, Amy!

I was very lucky to have spent the last semester studying with the foremost Beckett scholar, S.E. Gontarski, here at FSU. We spent about five weeks on Watt. An amazing book! Without a doubt one of my all time favorites.

I guess Beckett wrote this book while he and his wife were on the run from the Nazis. They had been hiding out at Nathalie Sarraute’s place, but someone tipped off the Nazis, so they had to split in the middle of the night with little more than the clothes on their backs. I guess they basically wandered around the south of France on foot — Beckett would take day jobs as a fieldworker or whatever he could find and then at night he worked on this book.

The ultimate, unanswerable question…if Watt actually conveyed the story to Sam and thus Sam is thought to be the narrator, how in the hell do we account for the opening pages in which Watt is not present?

“Then Watt said, Obscure keys may open simple locks, but simple keys obscure locks never.” (pg. 101)

Vol. 1 of his collected letters came out this year. I’m surprised I don’t see it on the obligatory annual sum-ups of the ‘best’ books, when nothing else came close. I could not recommend any book published recently as strongly.

Vol. 1 of his collected letters came out this year. I’m surprised I don’t see it on the obligatory annual sum-ups of the ‘best’ books, when nothing else came close. I could not recommend any book published recently as strongly.

Yes! yes yes! The POV is so crazy…not only for the narrative illogic that you point out, but also in its collapsing of character–the mind of Sam (somehow I didn’t catch his name when I read) seems to work just like the mind of Watt, and of Humpy Hackett.

That line you quote (124 in my very old Grove) is such goodness. I hadn’t tied it to the POV tangle, but now that I look back, it sits on the page facing the moment where, by my count at least, the narrator first inserts himself (“And if I do not appear to know very much on the subject…”). Is that the first time?

My own set of simple keys has surely not unlocked much of this, so my envy of the 5 weeks you spent on this with an eminent scholar will only be curtailed if you tell me more things you know, Chris. Though thanks already for reading my post and for the background on Watt’s composition–fascinating!

Yes! yes yes! The POV is so crazy…not only for the narrative illogic that you point out, but also in its collapsing of character–the mind of Sam (somehow I didn’t catch his name when I read) seems to work just like the mind of Watt, and of Humpy Hackett.

That line you quote (124 in my very old Grove) is such goodness. I hadn’t tied it to the POV tangle, but now that I look back, it sits on the page facing the moment where, by my count at least, the narrator first inserts himself (“And if I do not appear to know very much on the subject…”). Is that the first time?

My own set of simple keys has surely not unlocked much of this, so my envy of the 5 weeks you spent on this with an eminent scholar will only be curtailed if you tell me more things you know, Chris. Though thanks already for reading my post and for the background on Watt’s composition–fascinating!

I’m admiring but not adoring of Beckett’s fiction, but I really enjoyed this post.

I’m admiring but not adoring of Beckett’s fiction, but I really enjoyed this post.

[…] HTML Giant – Desert Island Reading: A Return to Beckett […]

I read wrote an essay for a lit class this term on holes and violence in Beckett’s Molloy, starting w/ a passage from Sartre’s Being and Nothingness on the nature of holes. Molloy struck me as one of the best novels I’ve ever read, and maybe one of the funniest.

Posted the essay on my blog if anyone wants to read it: http://lunchtimeforbears.blogspot.com/2009/12/from-void-to-violence-analysis-of-holes.html

I read wrote an essay for a lit class this term on holes and violence in Beckett’s Molloy, starting w/ a passage from Sartre’s Being and Nothingness on the nature of holes. Molloy struck me as one of the best novels I’ve ever read, and maybe one of the funniest.

Posted the essay on my blog if anyone wants to read it: http://lunchtimeforbears.blogspot.com/2009/12/from-void-to-violence-analysis-of-holes.html

this essay was also incredible, i have been thinking about it since i read it off yr tweet

holes and beckett are the best

this essay was also incredible, i have been thinking about it since i read it off yr tweet

holes and beckett are the best

Great post. Thank you!

Great post. Thank you!

when i first read this headline i thought someone was reading beckett at desert island (the comics store) in nyc & i got excited about the thought that maybe there would be a sam beckett comic or something, so i was disappointed when i realized that i was way off. but i liked the post so it’s cool.

i haven’t read watt or molloy yet (i know, right!) but i love how it is and the lost ones. want to read the trilogy.

when i first read this headline i thought someone was reading beckett at desert island (the comics store) in nyc & i got excited about the thought that maybe there would be a sam beckett comic or something, so i was disappointed when i realized that i was way off. but i liked the post so it’s cool.

i haven’t read watt or molloy yet (i know, right!) but i love how it is and the lost ones. want to read the trilogy.

awesome, i’m glad you liked it.

awesome, i’m glad you liked it.

Excellent post! In London this year I have had the pleasure of seeing Waiting for Godot (my favourite play ever) Endgame and a one-act called Catastrophe. I’ve also just finished Remembering Beckett/Beckett Remembering, an illuminating insight into the man by those who knew him and worked with him. His generosity and kindness too all he met is touching, I highly recommend this book. I’ve read Murphy, Watt is next on my list!

You can’t keep a good man down.

Excellent post! In London this year I have had the pleasure of seeing Waiting for Godot (my favourite play ever) Endgame and a one-act called Catastrophe. I’ve also just finished Remembering Beckett/Beckett Remembering, an illuminating insight into the man by those who knew him and worked with him. His generosity and kindness too all he met is touching, I highly recommend this book. I’ve read Murphy, Watt is next on my list!

You can’t keep a good man down.

nice essay, bryan. i think molloy is maybe one of the funniest novels i’ve read too, if not THE funniest. what’s funnier, really? beckett is very, very funny. nothing is funnier than unhappiness.

nice essay, bryan. i think molloy is maybe one of the funniest novels i’ve read too, if not THE funniest. what’s funnier, really? beckett is very, very funny. nothing is funnier than unhappiness.

Amy,

This is a lovely essay on a great book, and I especially appreciated your remarks on how Beckett “softens his own blows” with unexpected lyricism or with wit tucked into the driest corners.

There was one contemporary critic, I don’t recall the name, who said something like, “There’s only a frail, flickering source of light in this world and Mr. Beckett is trying his best to put it out.” But I agree with you, I read Beckett not as reveling in the limitations of existence he evokes but rather showing what can be done within them while yet not failing to face up to them.

Amy,

This is a lovely essay on a great book, and I especially appreciated your remarks on how Beckett “softens his own blows” with unexpected lyricism or with wit tucked into the driest corners.

There was one contemporary critic, I don’t recall the name, who said something like, “There’s only a frail, flickering source of light in this world and Mr. Beckett is trying his best to put it out.” But I agree with you, I read Beckett not as reveling in the limitations of existence he evokes but rather showing what can be done within them while yet not failing to face up to them.

Amy, thanks a million for this. It was completely beautiful and it really synthesized some important things about Beckett for me. I absolutely agree with you when you say that “Watt must be Beckett’s most generous book and his truest” (I think Beckett’s entire work, actually, is nothing else than a kind of terrible, if ethical, generosity). But I’m not sure I extend that insight to a statement like “it’s a better life for this glassy mirror of it”, at least in the recuperative sense in which I thin it’s tended here. It’s true you keep the knowledge that Beckett gives us hell on earth, but still, there’s a tendency to dissolve the problems of Beckett – to rehabilitate Beckett – by reading certain moments in his work as the manifestations of a kind of hopeful Beckett. I feel that doing so is to give away his accursed, ethical gift. It’s not that a moment like the one you cite at the last from Watt is not, indeed, an instance of the manifestation of a promise of ‘a better life for this glassy mirror of it’ but that better life is itself the height of horror for Beckett.”The day without precedent, at last” isn’t really salvational; it’s coercive – “whether he liked it or not”. Generally, I tend to think we dissolve the full depth of the disasters Beckett so faithfully represents to us by finding types of grace as grace in his work. Existence delivers us from horrors in Beckett, but it does so dumbly, almost in a kind of perverse contrariness to itself, into the better-in-worst, that becomes the ongoing perfection of the worst. In the same spirit of existence’s perverse refusal to even adhere to the fundamental principle of moving directly worstward that it seems to posit, we even can sometimes deliver ourselves from the full disaster of disaster and, in so doing, exercise an agency that, in its exercise, mires us in many entanglements that our freeing up of ourselves didn’t quite count on. I agree with Alan above in that I certainly don’t think Beckett revels in the limitations of existence – unless we take revel in the sense of revelation, itself a flopping void – and I also agree that he shows what can be done within life’s limitations while continuing to face up to them. But the ‘possible’ is, in no way whatsoever, a positive thing for Beckett. What moves him to the good toward others – such as his anti-fascistic politics, say, or his startling care for absolutely everything he represents – is the perversity of caring in relation to the fickle worstfulness of reality. I think Beckett is entirely relentless in this. It’s his core assertion. There is no reprieve, just the foreclosed absolute of the shut-open future, the day without precedent, this day like the one before it in its lack of precedence, this never before arrived allotment of foreshortened maybe we cannot make so different nor deny. Care is a kind of commitment, in such circumstances: not to the alleviation of anything but against the instantiation of everything as is. There is no excuse for tenderness except its excuselessness, a fugitive’s insight. The lack of any excuse for any of us before the sickly reality we are and in is for Beckett, with Kafka, the very thing which brings forth an obligation to emancipate.

Amy, thanks a million for this. It was completely beautiful and it really synthesized some important things about Beckett for me. I absolutely agree with you when you say that “Watt must be Beckett’s most generous book and his truest” (I think Beckett’s entire work, actually, is nothing else than a kind of terrible, if ethical, generosity). But I’m not sure I extend that insight to a statement like “it’s a better life for this glassy mirror of it”, at least in the recuperative sense in which I thin it’s tended here. It’s true you keep the knowledge that Beckett gives us hell on earth, but still, there’s a tendency to dissolve the problems of Beckett – to rehabilitate Beckett – by reading certain moments in his work as the manifestations of a kind of hopeful Beckett. I feel that doing so is to give away his accursed, ethical gift. It’s not that a moment like the one you cite at the last from Watt is not, indeed, an instance of the manifestation of a promise of ‘a better life for this glassy mirror of it’ but that better life is itself the height of horror for Beckett.”The day without precedent, at last” isn’t really salvational; it’s coercive – “whether he liked it or not”. Generally, I tend to think we dissolve the full depth of the disasters Beckett so faithfully represents to us by finding types of grace as grace in his work. Existence delivers us from horrors in Beckett, but it does so dumbly, almost in a kind of perverse contrariness to itself, into the better-in-worst, that becomes the ongoing perfection of the worst. In the same spirit of existence’s perverse refusal to even adhere to the fundamental principle of moving directly worstward that it seems to posit, we even can sometimes deliver ourselves from the full disaster of disaster and, in so doing, exercise an agency that, in its exercise, mires us in many entanglements that our freeing up of ourselves didn’t quite count on. I agree with Alan above in that I certainly don’t think Beckett revels in the limitations of existence – unless we take revel in the sense of revelation, itself a flopping void – and I also agree that he shows what can be done within life’s limitations while continuing to face up to them. But the ‘possible’ is, in no way whatsoever, a positive thing for Beckett. What moves him to the good toward others – such as his anti-fascistic politics, say, or his startling care for absolutely everything he represents – is the perversity of caring in relation to the fickle worstfulness of reality. I think Beckett is entirely relentless in this. It’s his core assertion. There is no reprieve, just the foreclosed absolute of the shut-open future, the day without precedent, this day like the one before it in its lack of precedence, this never before arrived allotment of foreshortened maybe we cannot make so different nor deny. Care is a kind of commitment, in such circumstances: not to the alleviation of anything but against the instantiation of everything as is. There is no excuse for tenderness except its excuselessness, a fugitive’s insight. The lack of any excuse for any of us before the sickly reality we are and in is for Beckett, with Kafka, the very thing which brings forth an obligation to emancipate.

Hi David, thanks for reading and for your nice words and for this considered response. I didn’t mean my last statement to seem recuperative. I have no project of rehabilitating or therapizing Beckett. “Better life” probably does sound that way, but I meant better life as honester life, invested with this, as you say, a fugitive’s insight into that “fickle worstfulness of reality.” Maybe I’m a bit old-fashioned in what I want from art, but I find I need the particular terror and pity that I access when reading Watt.

I think this speaks debate speaks, to me, of a kind of larger issue I have with the idea of art not being therapeutic. Maybe the trouble is in how we define therapy. For if art didn’t do anything for us, or to us, that we wanted it to do on some level, why would we turn to it? A realer confrontation with what’s before us, as for example imparted by Watt–that must serve us somehow, just not in the way pop psychologists think we need to be served.

Hi David, thanks for reading and for your nice words and for this considered response. I didn’t mean my last statement to seem recuperative. I have no project of rehabilitating or therapizing Beckett. “Better life” probably does sound that way, but I meant better life as honester life, invested with this, as you say, a fugitive’s insight into that “fickle worstfulness of reality.” Maybe I’m a bit old-fashioned in what I want from art, but I find I need the particular terror and pity that I access when reading Watt.

I think this speaks debate speaks, to me, of a kind of larger issue I have with the idea of art not being therapeutic. Maybe the trouble is in how we define therapy. For if art didn’t do anything for us, or to us, that we wanted it to do on some level, why would we turn to it? A realer confrontation with what’s before us, as for example imparted by Watt–that must serve us somehow, just not in the way pop psychologists think we need to be served.

David, Interesting contribution, as usual. I’m not sure that “whether he liked it or not” implies coercion any more than “with patience it would come” implies a promise of salvation. Just because the coming of day is independent of the subject’s will doesn’t mean it’s necessarily unwelcome, right? I’m not denying that “whether he liked it or not” foregrounds the possibility of not liking it, but it doesn’t insist on it, either. Just as the fact that the day to come is “unsoiled” doesn’t mean it won’t get shit on right away but even so leaves open other possibilities, however unlikely–each new day, after all, being radically “without precedent.” I think Beckett’s characters are stuck not in hell, where there truly is no hope, but in purgatory, where hope exists but is continually deferred. In Kafka’s formula, since you bring him up, (I’m quoting from memory here) “There is hope, infinite quantities of it, but not for us.”

Also not sure where you’d find an “obligation to emancipate” in either author’s work, though significantly neither one rejected efforts in that direction (by their own lights, that is) out of hand.

David, Interesting contribution, as usual. I’m not sure that “whether he liked it or not” implies coercion any more than “with patience it would come” implies a promise of salvation. Just because the coming of day is independent of the subject’s will doesn’t mean it’s necessarily unwelcome, right? I’m not denying that “whether he liked it or not” foregrounds the possibility of not liking it, but it doesn’t insist on it, either. Just as the fact that the day to come is “unsoiled” doesn’t mean it won’t get shit on right away but even so leaves open other possibilities, however unlikely–each new day, after all, being radically “without precedent.” I think Beckett’s characters are stuck not in hell, where there truly is no hope, but in purgatory, where hope exists but is continually deferred. In Kafka’s formula, since you bring him up, (I’m quoting from memory here) “There is hope, infinite quantities of it, but not for us.”

Also not sure where you’d find an “obligation to emancipate” in either author’s work, though significantly neither one rejected efforts in that direction (by their own lights, that is) out of hand.

Amy, oh yeah, absolutely. It’s true there is a lot more in the idea of art as therapy than its total bastardisation as a concept by pop-psych. Weirdly, I think a lot of people already subscribe to the notion without quite realising: anybody, for instance, who tracks with Lacan, for instance, or more broadly Zizek, in theoretical terms, accepts a psychoanalytic conception of Fantasy as a kind of involuntary therapy – even if it’s entirely excoriating and relentless and pitiless and scorching. Therapy certainly doesn’t have to be character building. It can confirm one’s pathology.

Alan, hi, man. Unfortunately out of time (and steam) to give your reply the answer it deserves but I do hold that ‘whether he liked it or not’ implies coercion not because one is more likely to not like it than to like it (Beckett’s too wise to stake a position on that, as both assessments occur) but because it happens in perfect indifference to the orientation of one’s desire in advance: it simply doesn’t alter its bound occurrence that one likes or does not like it. So you’re quite right to say that the coming of the day could be quite welcome by the subject even if it were detached from the subject’s will but the day wouldn’t much care for such welcoming either and thus, unavoidably, comes pre-set at cross-purposes to that welcome. Not to mention in Beckett one has to welcome the new day because the old one was always so terrible: a point both of ethical solidity (the new of the new day can never be surmounted as the same old thing because its opportunity is far too valuable to simply moot) as well as a depressing realisation of fortunes (the new day is a wretched opportunity, inevitably, wretched in that we cannot but embrace it, voluntarily or involuntarily, though it will smother us). I also do think there is an absolutely obligatory emancipatory decree in both Kafka and Beckett. Kafka’s obligation to emancipate is found in the very fact he wrote, I think. That said, I don’t think he was exactly approving of it. As you’d know, he hated his writing, in part, because it was an abomination to him in its emancipatory nature, its otherworlding. Kafka partly wanted no more world of any kind. But he also hated himself for it because he never wrote ‘well enough’ (or, in his own estimation, could never see through the emancipation of himself writing innately was but never made happen). In both cases, liked or not liked, the emancipatory was obligatory. As for Beckett, I think he was less at odds with writing but the obligation to emancipate is as obligatory for him in that the fickle worstfulness of reality summons one to a burnt conscience (but never burnt-out, hence its enduring agony).

Amy, oh yeah, absolutely. It’s true there is a lot more in the idea of art as therapy than its total bastardisation as a concept by pop-psych. Weirdly, I think a lot of people already subscribe to the notion without quite realising: anybody, for instance, who tracks with Lacan, for instance, or more broadly Zizek, in theoretical terms, accepts a psychoanalytic conception of Fantasy as a kind of involuntary therapy – even if it’s entirely excoriating and relentless and pitiless and scorching. Therapy certainly doesn’t have to be character building. It can confirm one’s pathology.

Alan, hi, man. Unfortunately out of time (and steam) to give your reply the answer it deserves but I do hold that ‘whether he liked it or not’ implies coercion not because one is more likely to not like it than to like it (Beckett’s too wise to stake a position on that, as both assessments occur) but because it happens in perfect indifference to the orientation of one’s desire in advance: it simply doesn’t alter its bound occurrence that one likes or does not like it. So you’re quite right to say that the coming of the day could be quite welcome by the subject even if it were detached from the subject’s will but the day wouldn’t much care for such welcoming either and thus, unavoidably, comes pre-set at cross-purposes to that welcome. Not to mention in Beckett one has to welcome the new day because the old one was always so terrible: a point both of ethical solidity (the new of the new day can never be surmounted as the same old thing because its opportunity is far too valuable to simply moot) as well as a depressing realisation of fortunes (the new day is a wretched opportunity, inevitably, wretched in that we cannot but embrace it, voluntarily or involuntarily, though it will smother us). I also do think there is an absolutely obligatory emancipatory decree in both Kafka and Beckett. Kafka’s obligation to emancipate is found in the very fact he wrote, I think. That said, I don’t think he was exactly approving of it. As you’d know, he hated his writing, in part, because it was an abomination to him in its emancipatory nature, its otherworlding. Kafka partly wanted no more world of any kind. But he also hated himself for it because he never wrote ‘well enough’ (or, in his own estimation, could never see through the emancipation of himself writing innately was but never made happen). In both cases, liked or not liked, the emancipatory was obligatory. As for Beckett, I think he was less at odds with writing but the obligation to emancipate is as obligatory for him in that the fickle worstfulness of reality summons one to a burnt conscience (but never burnt-out, hence its enduring agony).

OK, I don’t think we’re far apart at all, but to say necessity is always coercive (that is, not just beyond but against one’s will) is to use the latter term in a rather loose sense. That’s a nuance, though.

And now I understand that you’re talking about those authors’ own felt obligation to emancipate through their writing, not some universal obligation they believed in. I can see how the work of both men was driven by a larger task (not sure I would define it the way you have) that they felt inadequate to, yet felt obliged to pursue.

Not to prolong this, but I think you’re much closer in saying Kafka hated his writing because it wasn’t adequate to the task he set for it than in supposing he didn’t value the task itself. Far from wanting no more of the world, Kafka sacralized it; it was his own existence he saw as an abomination.

OK, I don’t think we’re far apart at all, but to say necessity is always coercive (that is, not just beyond but against one’s will) is to use the latter term in a rather loose sense. That’s a nuance, though.

And now I understand that you’re talking about those authors’ own felt obligation to emancipate through their writing, not some universal obligation they believed in. I can see how the work of both men was driven by a larger task (not sure I would define it the way you have) that they felt inadequate to, yet felt obliged to pursue.

Not to prolong this, but I think you’re much closer in saying Kafka hated his writing because it wasn’t adequate to the task he set for it than in supposing he didn’t value the task itself. Far from wanting no more of the world, Kafka sacralized it; it was his own existence he saw as an abomination.

Alan, again, sorry to be too brief, I’m kind of in a mind funk atm. I take the point about coercion as meaning most precisely that which is against, rather than simply beyond one’s will but I take the day in Beckett to be coercive precisely because it is literally “against” will as a concept we use to think autonomy, that which we will or do not will. In a way, it sort of attaches its own will to us, almost in the manner of Robert Heinlein’s Puppet Masters. Also, I did mean a universal obligation to emancipate, actually. I find their individual lives were pained expressions of that obligation. Such an emancipative directive has no bearing on an actual systemic political commitment in the lives of either. It’s an ethics against reality, though not anti-realist thereby: an ethics that they as conscience-ridden cannot refute or refuse. And it exists impersonally, even cruelly, in the same way that terror does. Thanks for the thoughts, man.

Alan, again, sorry to be too brief, I’m kind of in a mind funk atm. I take the point about coercion as meaning most precisely that which is against, rather than simply beyond one’s will but I take the day in Beckett to be coercive precisely because it is literally “against” will as a concept we use to think autonomy, that which we will or do not will. In a way, it sort of attaches its own will to us, almost in the manner of Robert Heinlein’s Puppet Masters. Also, I did mean a universal obligation to emancipate, actually. I find their individual lives were pained expressions of that obligation. Such an emancipative directive has no bearing on an actual systemic political commitment in the lives of either. It’s an ethics against reality, though not anti-realist thereby: an ethics that they as conscience-ridden cannot refute or refuse. And it exists impersonally, even cruelly, in the same way that terror does. Thanks for the thoughts, man.

Thanks a lot for the response(s), David. Take care.

Thanks a lot for the response(s), David. Take care.

thanks to the both of you, seriously. you’ve given me lots to think about.

thanks to the both of you, seriously. you’ve given me lots to think about.