Four! Mark Neely Interview.

Lately chapbooks design/appear more glow than many book-books. Example winner of Concrete Wolf contest. Interview below:

The Food Network has perfected the cooking show by turning it into soft porn. The hosts actually moan when they taste what they have made. And although the chefs on the show are grating their own horseradish and making their own sausage, most of the commercials are for American cheese slices and frozen dinners. That doesn’t seem common to me. It seems insane.

No matter how hard humans try and wall ourselves off from the natural world, we still have mites living in our eyebrows.

Online publishing is young. Like a young person it is energetic, cocky, innovative, various, unstable, and full of shit. I’m excited to be around to watch it grow up.

1. Why four?

The number came out of the form. I was trying to write poems that were visually striking (but not in a this-looks-like-a-swan sort of way), and I liked how the four blocks of prose made a kind of abstract window. The form is solid, symmetrical, but the language is unstable, fragmentary, hopefully unpredictable. I like that the sections can be read in different orders. Also—four, fore, for, our, ore, or, ur.

2. Robert Creeley—who, of course, you note in the epigraph of Four of a Kind–states, “The common is personal.” In the beginning of this collection, and throughout, it seems the “I” keenly observes the world, and then situates itself as part of, or playing off, that observed reality. For example, on the opening page, a frazzled, late-to-work “I” is quickly played off a “crazed cat” and an “actual peacock.” Then we get this wonderful desistance to the segment:

“The peacock, in his madness, is not half as beautiful as you might imagine.”

Following this segment the most common appliance, the TV, is turned to a cooking show, complete with beautiful host and exquisitely prepared food—immediately transferred to the hurried reality of “We dash home, open cans and slap something together…”

Will you discuss the idea of common as personal, as a technique, or a poet’s way of viewing the world?

Some say the job of writers is to find the ordinary in the extraordinary. But I don’t think anything is common or ordinary if you look at it long enough, or from the right angle. Elizabeth Bishop wrote, “The Seven Wonders of the World are tired / and a touch familiar, but the other scenes, / innumerable, though equally sad and still / are foreign.”

Television and its offshoots inhabit every aspect of our lives. Screens are more common than mice. And yet they are foreign.

The Food Network has perfected the cooking show by turning it into soft porn. The hosts actually moan when they taste what they have made. And although the chefs on the show are grating their own horseradish and making their own sausage, most of the commercials are for American cheese slices and frozen dinners. That doesn’t seem common to me. It seems insane.

3. What kinds of anxieties do you have when you sit down to write?

The anxieties I have when I sit down to write are nothing compared to the anxieties I have in other situations. Sitting down to write usually makes me feel pretty good, comparatively. But I guess I have most of the usual intrusive thoughts at times: Is this any good? Will anyone ever read it? Who cares?

4. Every poem here is in four segments, on the page, with white space, actual white perpendicular stripes of white in-between the blocks of words, with wide margins, the blocks pinned on the page with some crossroad, a cross, something binding them together…

What is the role of the visual structure of the poems on the page?

See question number one.

5. Following up on the previous question, how much did you work with the publisher on this book? The look, the cover, the page, etc. Can you give us a quick glimpse of what that process is like, the practical side of putting the collection together?

My editor, Lana Ayers at Concrete Wolf, was incredibly generous and involved me in the entire process. My friend Tim Berg had a photo I wanted to use and the book designer at the press designed an amazing cover around it. They made the book an unusual size and shape to accommodate the structure of the poems, even though it was more expensive to print.

Concrete Wolf really spoiled me—everything I asked for they did. Except once, when what I asked for was stupid, then they gently convinced me otherwise.

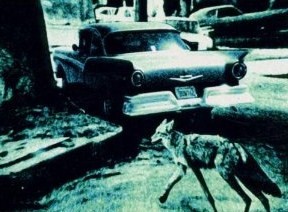

6. The cover of Four of a Kind is a photo of a dilapidated (abandoned?) automobile (truck?) seemingly overtaken by nature, rust, leaves…

“My coffee is no crystal lake…”

“The opossum was flattened by days of traffic, turning the color of the road.”

“…clouds billow from the horizon like factory smoke.”

For all the stunning, lush imagery of nature on the page, it seems to always be intruded upon, or usually, by roads, coffee cups, factories—Men. I think of those pockets of nature we see all around the Midwest, little lots and thickets, in between houses and streets of strip malls.

What is the natural world’s place in your work?

I think it’s a VW bus.

This intrusion of human life on “nature” is something I see a lot of in Tim Berg’s photographs (including the one on the cover). Also decay—the intrusion of nature on humans and manmade things.

Another way of looking at it—there is no separation between “natural” and “human.” Oil is part of nature, both when it sits calmly under the earth and when humans pump it up, refine it, put it in their cars, and drive to the bar. Humans are animals, whether they are shivering naked in a cave listening to the howling of coyotes or sitting in the cockpit of a stealth bomber. This is an easy thing to forget. No matter how hard humans try and wall ourselves off from the natural world, we still have mites living in our eyebrows.

7. You work as a creative writing professor. Do you think writing poetry can be taught?

Can history be taught? Can you be a historian without a PhD in history? If you get a PhD in history, will you know more about the study of history than you knew before you began the degree? Will you definitely be a great historian? Will some of the things you learn in your PhD program (both from professors and other students) actually stifle your passion for history, or cut you off from ideas you might have had if you just read a bunch of books and talked to your friends about history? Remember back in the good old days when there were no PhDs in history and all the historians were awesome (Thucydides, Xenophon, etc.).

I don’t think there is a general answer to a question like this. It depends on the writer, the teacher, the specific situation. I think some writers benefit from taking classes in writing, and from being in programs where they are part of a community of writers—I certainly think I did. Of course you don’t have to go to school to find a community of writers—there’s also Brooklyn and the internet.

8. A lot of voices in this collection. Personas. Yet each voice has a confidence. As a reader, I had no trouble with the “I” being this or that historical or legendary personage. I am assuming a role of research. How much is research a formal part of your writing process?

I didn’t do a lot of formal research but I wrote these poems over a long period of time, and during that time I read a lot of books and watched movies and talked to interesting people, and a lot of that material found its way into the poems.

9. What published book of poetry do you wish you had written? Why?

James Wright’s Shall We Gather at the River. Or, if you prefer the living, Brigit Kelly’s Song.

Both those books have enormous hearts.

10. “We’re waiting for an invisible galaxy to eat the Milky Way and all its boiling angels, are driven by a god with a golden whip, by jingles and tanned heroes, and punk songs like garbage cans run over by the truck. Let us pray.”

Such tight, shaped words, so much heated imagination. I’m wondering do these images and ideas appear formed, or nearly, or is this a result of meticulous editing? What is your editing process?

I’m an obsessive editor. I edit for years. A lot of these poems were published in magazines, but I kept editing them after they were published. Some of the poems here are quite different from the original published versions. I wouldn’t be surprised if I keep editing these poems in the years to come.

Lately I’ve been trying to teach myself to stop before I ruin things. I worry about

stripping poems of their energy with too much editing sometimes.

11. Do you keep a journal or diary?

Not really. I do scribble words on whatever notebook or piece of paper I have around. I send emails to myself.

12. I notice you publish in print and online. What does the online literary world mean to your poetry, or the world of contemporary poetry in general?

Sandy Huss once showed me a timeline of the history of writing—her point was to show how tiny a portion of that history is occupied by the codex—the “book” as we know it. That made a huge impression—like the timelines I saw as a kid showing human existence as a speck in the whole history of the planet.

Online publishing follows logically from other technologies (the printing press, the mimeograph machine, etc.) that have made the means of production available to more people. Democratization. Online publishing is young. Like a young person it is energetic, cocky, innovative, various, unstable, and full of shit. I’m excited to be around to watch it grow up.

That said, I also love printed books. I like the sound and shadows of turning pages. I edit a print journal, The Broken Plate, with my students at Ball State. Once the thing is printed, the text is fixed (including typos and other errors). That makes for a specific kind of anxiety for the editors.

13. Four of a Kind seems drenched in the passage of time. Again, possibly we return to the cover photo. Will you discuss the idea of time in this collection?

I tried to get a rich past, present and future in every poem. Some of the poems (“Four Years” for example) consider the same subject over a period of time. Writing is outside of time in that you can have a year go by in a sentence, or a minute can take up many pages. I want to expand time in places, compress it in others.

A poem that comes to mind is James Dickey’s, “Falling,” about a flight attendant who falls to her death from an airplane. Dickey stretches out those minutes when the woman is falling over pages and pages. But by the end of the poem, I feel my own lifespan contract with the realization that I am also falling toward my death.

14. How did you begin to write poetry?

I remember reading an e.e. cummings poem for school when I was a kid (“Buffalo Bill’s / defunct”). I had to write a report on it or something, and my mom was helping me. She asked why cummings wrote “defunct” instead of “dead.” In an instant, the idea of an author was visible to me. I was writing stories and poems before that moment, but from then on it was something I consciously thought about.

Tags: Chapbook, Concrete Wolf, Mark Neely

Not sure what it indicates here, but that picture, among the interview excerpts, of the coyote running up to the curb behind the old car is also used on the cover of Unida’s Coping with the Urban Cowboy frisbee. John Garcia – excellent metal singer. Human Tornado – great metal-by-numbers.

(You object to art-by-numbers? The common can become personal.)

–

It looks like interview question 4 experienced an interruption of the embolden function. ?

–

“History” and “creative writing” are pretty different domains of practice.

Despite the absence of ‘experiment’, and despite the enfolding of observer bias directly into historical investigation – as much constitutive as it is obstructive, eh? – , historical research proceeds in a scientific way: this is what counts as ‘evidence’; these are acceptable methods of discussion; these count as conclusions drawn methodologically so as to support or refute presumptions (‘hypotheses’).

Although – of course – there’s technique in creative writing, and more or less (often much less) verifiable criteria of aesthetic comparison and judgment, still, “creative writing” resists a framework of scientificity successfully in a way that “history” does not.

Or not?

that is exactly where I swiped the photo. Someone should sue me, now.

thanks for the catch on the error–I fixed it.

Well, he sort of set up the history ideas a rhetorical, I think, the addressed his own question in the second part.

Excellent interview, Sean. I’m glad to read this.