Author Spotlight

Massumi and Malbec 2: Guest Post by Corey Wakeling

Since Brian Massumi’s Parables for the Virtual is in effect a piece of Deleuzian theory and by nature indulges in micro-theses embedded in paragraphs, I feel it’s worth making a veritable castle gate out of the primary thesis put forward by ‘The Bleed’ to help us all start on the right foot with this week’s chapter. So here it is:

Since Brian Massumi’s Parables for the Virtual is in effect a piece of Deleuzian theory and by nature indulges in micro-theses embedded in paragraphs, I feel it’s worth making a veritable castle gate out of the primary thesis put forward by ‘The Bleed’ to help us all start on the right foot with this week’s chapter. So here it is:

Rethink body, subjectivity, and social change in terms of movement, affect, force, and violence – before code, text, and signification.

As we know from Chapter One, this book’s primary task is to re-introduce theories of affect into the cultural theory landscape. By nature, as definitionally a term used to describe non-cerebral, non-rational, and emotional influence and intensity – intensity being Massumi’s privileged noun – affect was the victim of disregard under postmodern theory due to its seemingly impossible assimilability within methodologies of cultural analysis and deconstruction. As lit theory students, we know well one of our first-year edicts: the affective fallacy. Affect qualified is emotion, but Massumi nips this in the bud early on in Chapter One when he says that, “Intensity is qualifiable as an emotional state and that state is static…” This leads us to ‘The Bleed’, and an important distinction: affect, also known as intensity, bleeds over our receptivity to it. What would otherwise be approached as the language of subjectivity, or the language of human feeling, here is recovered as a site that must be investigated as a “resonating chamber”. Receiving affective energy, the body then responds to the stimulus by making sense of it, first bodily (and this has vicissitudes that I will later explain) and then in language. What we have in this chapter is the concerted attempt to construct an incorporeal materialism – a Massumian appellation for Deleuze’s transcendental materialism – that accounts for the real, material influence of virtuality on the actual, and the actual’s communication through virtuality. So, the task is to include sensation that is either too small or too amorphous or opaque as a part of our critical programmes, and in the process perhaps succeed in following Nietszche’s admonishment of being human-all-too-human and move towards ontological analysis that accounts for becomings via means that are not necessarily entirely explicable as purely sociological or psychological phenomena. Massumi explains that cultural theory as it stands is not all wrong, it’s just that we need to be articulating a language and a philosophy that better deals affect and intensity.

The main point of analysis for the ‘The Bleed’ is Ronald Reagan’s recounting of his one success as an actor, that is, playing an amputee in King’s Row. Massumi precedes this scenario with explanations from Reagan that after seeing himself in dailies in other films, even with the perspective of others embodied by the camera he still sees his plain, old, everyday self. Massumi speaks of this as Reagan’s not going far enough, seeing only a mirror-image in the perspective of the camera. It isn’t that Reagan isn’t playing someone else, it is that some resemblance still takes place, “that it doesn’t take the actor far enough outside of himself.” Massumi articulates this desire to see someone else as the desire to move from ‘mirror-vision’ to ‘movement-vision’, for it is movement-vision which manages a self-distancing, a becoming. Becoming indicates the important productivity of artifice, the productivity of the virtual. In this case, Reagan wants to embody the “body of another fellow,” an amputated body from the perspective of the movement-image, which is a collective one. We hear of Reagan’s process, meeting people of all kinds, people who are amputees and people who know amputees, but this absorption is essentially epistemological, a gathering of knowledge. The stories leave him “wan and worn” and he stumbles into the studio seemingly without hope of success. The rig they have waiting for him will create the illusion of Reagan’s being an amputee. He sits in it for an hour, and suddenly becomes terrified by the suspense of this. And then he asks himself the phrase that will become the title of his autobiography: “where’s the rest of me?” This virtual-but-actual rig “virtually amputates him,” the director’s call for “Action!” forces Reagan’s recognition of being on the cusp of transition, thereby initiating the event of Reagan’s becoming-part-subject. Notice that Massumi privileges exterior stimuli, the psychological gesture of Reagan being the development of different receptivities and a preparedness for the event, not merely the will to become-other. Understanding incorporeal materialism is simple here: everything about Reagan’s speculations about the rest of him, the setting of the event, the desire to be a different body, is virtual, but causes actual change, each of these virtualities having actual ramifications. Reagan’s questioning, “where is the rest of me,” will become his reason for entering politics and becoming President of the United States since the role of the politician is the actor par excellence: playing myriad roles via an enormous social movement-vision. Naturally, in using Ronald Reagan, such a becoming is not all positive. Positivity is not the postulate. The postulate is of a process that enables a becoming-other and valorizes “technologies for making seeming being… something central of liminality.”

The philosophical implications of Massumi’s sophisticated model for affect are far-reaching. We have an exigent model for accounting for the body’s receptivity and articulation of the event, for the layers of corporeal understanding of incorporeal stimulus and the significance of anticipating the event through the incorporeal. This is as much a theory of receptivity as it is a new articulation of the event, since the event is wet with the blood of incorporeal suspense. Massumi speaks about Reagan’s sitting in the rig contemplating and then becoming fearful as a “prolonged suspense,” suspense being distinct from expectation as affect is distinct from apprehended, articulated emotion. Since Reagan saw only his plain, old self in films prior to this, even with the multi-perspectivism of the camera, each view embodying a possible other, it is not until Reagan closes his eyes in the rig on the cusp of complete mental exhaustion that the illusion created defies the recognition of its author. This is what Massumi calls “the body without an image,” the infra-empirical space that is constructed by the movement-image, one in which the self no longer resembles itself. We see Deleuze’s Body-without-Organs here in Reagan’s silent, blind moment on the cusp of becoming. It starts with the cultivation of an imageless body that is filled up with the suspense of performative and epistemological anticipation which then, as an organless body that does not introject the event but rather provides the flat surface for it, with the director’s “Action!” participates in the event and becomes-other. The becoming-other here is not entering the body of “another fellow” as Reagan puts it, that is just an aspect. Reagan becomes incomplete, on an ontogenetic journey into futurity through politics. Again: we must think in terms of a space of resonation. Massumi goes on to include tactile sensibility (the reflexivity of the body to tactile stimulus), and visceral sensibility, our receptivity to suspense as it has been articulated previously. Massumi sees these sensibilities as informing our subject-object relations, not the other way round. This puts the primacy of sensation (tactile plus visceral sensibility) in direct relation to the event, since what we are left with in Massumi’s programme is the urgency to harness and build awareness to our receptivity to the event as well as its immanent production through artifice. What Massumi wants us to realise is that “passage precedes position.” With this radical understanding of sensation (both the ‘feeling’ and the ‘act of feeling’) as constituted of cooperating reflexivities that flinch prior to the understanding of that which we flinch from, we move reflexively with affect before we know where we are going. If we are to cultivate ontological enquiry, we must also develop ontogenetic enquiry, or enquiries into becoming. We must cultivate a receptivity to and awareness of sensation that is sophisticated to the degree Massumi articulates, and discover the ongoing multiplicity of a becoming-other rather than the closure of achieving the being-Ideal. Most important, understand the becomings responsible for a being-Ideal; emphasise the middle over the terminus. Or, in Massumi’s words:

DIS-SEVER THE IMAGELESS FROM THE IDEAL.

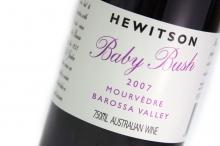

With this notion I’d then like to approach the wine I’ve been drinking. This is Massumi and Malbec after all. Now I can’t purport to know much about malbec, but I do know a little about mourvèdre, also know as mataró. These are all spectacularly emmie. And sophisticated? Well, I’m not afraid to say that I think it might be strong competition against the fruitier malbec, and I’ll tell you why. When Massumi speaks about cultivating a body-without-an-image, the imageless body, that disjunctive state at the cusp of becoming, he privileges the pure receptivity that comes from suspense. To have suspense, you must have an overflow of affect, a process, a specific continuity. When it comes to continuity, and drawn-out suspense, mourvèdre is your wine. I have been sucking on a bottle of Hewitson’s 2007 Baby Bush mourvèdre from the famous Barossa region here in Australia. The Baby Bush is admittedly the less premium of their production mourvèdres, but of an appeal entirely different to the Old Bush mourvèdre, and for half the price. Every discontinuity in this provocative wine has been walled up, creating a tannic mouth-feel that is pleasing but not centre-stage, the resonation of a beginning-middle-and-end continuity without break or inconsistency. The black cherry, almost mulberry fruit integrates and diffuses gracefully into a tender cigar box finish far more subtle than a Barossa shiraz. The wine is consistent with every mouthful and yet you, the drinker, in transition, are a different wine-drinker with each one. That is, if you follow its injunctions. If the Old Bush has more longevity, more melodrama, the Baby Bush plays with you , and then seduces you. Its continuity is impenetrable, and good luck trying to draw a gratifying denouement out of it. At this stage, thinking back to the Old Bush, I still prefer that hoary, elegant showstopper, but that is my failure because I still envy the old bastard, still harbour the ideal. There is something too French about it, too old-world, too mellow. The Baby Bush rekindles that belief in me that criticism – especially wine criticism – is too often founded on stale discourses and the opinions of their defenders, a wholly stagnant manner in which to build knowledge and understand sensation and all its multiplicity. Criticism should be in a process of consistent self-renovation, following the lead of sensation. Wine circles are worse than literary ones because unless you come around to the understanding that, no, in fact the Bordeaux is the better wine, then, like in a maths exam, you simply fail on the finals in sensibility. In a New World wine setting this is not as troublesome a reality. Wonderful micro wine revolutions are taking place (each grape variety being stretched to new possibilities). Sipping the Baby with Massumi in mind perhaps I can make that radical transition myself, following the lead of sensation into actual difference and find my phrase like Reagan, which surely can only be: “where is the rest of my wine?” Which is of course, give us more New World mourvèdre.

Tags: brian massumi, parables for the virtual

I love this. Thanks, Corey.

I love this. Thanks, Corey.

Why don’t you just call this Massumi and Wine? Oh, right… no alliteration. Two posts, and we’ve got a Rioja (which I like, don’t get me wrong), and now a mourvèdre. I wanna do a guest post. Massumi and Thunderbird.

Why don’t you just call this Massumi and Wine? Oh, right… no alliteration. Two posts, and we’ve got a Rioja (which I like, don’t get me wrong), and now a mourvèdre. I wanna do a guest post. Massumi and Thunderbird.

I wish this had been going when I read this book the first time. I really appreciate your thoughts here.

I wish this had been going when I read this book the first time. I really appreciate your thoughts here.

The difficult thing about this chapter is that it makes claims about affect and a slightly new articulation of sensibility a la the BwO, but the example of Reagan’s becoming-part-subject, the virtual as the actual’s own excess, really only substantiates the BwO, the resonating chamber, and not some greater call for affect theory. This is why is paramount to read on, since Chapter Four substantiates to an exceptional degree modes in which affect, and theory’s incorporation of it, accounts for the relay of sensation, where subject and object intermix. It’s compelling stuff. But I really like all the different perceptions Massumi pinpoints in this chapter, this process before position.

The difficult thing about this chapter is that it makes claims about affect and a slightly new articulation of sensibility a la the BwO, but the example of Reagan’s becoming-part-subject, the virtual as the actual’s own excess, really only substantiates the BwO, the resonating chamber, and not some greater call for affect theory. This is why is paramount to read on, since Chapter Four substantiates to an exceptional degree modes in which affect, and theory’s incorporation of it, accounts for the relay of sensation, where subject and object intermix. It’s compelling stuff. But I really like all the different perceptions Massumi pinpoints in this chapter, this process before position.

Hewitson’s should pay you pile for this! We should pay you a pile for this! For god’s sake, somebody pay the man!

Thank you Corey.

Hewitson’s should pay you pile for this! We should pay you a pile for this! For god’s sake, somebody pay the man!

Thank you Corey.

[…] up with a reading group that has been erratically going on over at HTML Giant. So far the first two chapters have been […]

Goodness.

I’ll need two bottles of Hewitson to find my way into Massumi’s work!!!

Bravo Corey for making sense of him with just one.

Goodness.

I’ll need two bottles of Hewitson to find my way into Massumi’s work!!!

Bravo Corey for making sense of him with just one.