I saw Matthew Vollmer’s Inscriptions for Headstones on the floor, alongside a gun cleaning kit and a disc golf disc and a dead spider. I picked it up. I actually began the book thinking I would skim through it, maybe perusing a third, just seeing what it was all about. I read the entire book, from first to last page, in one sitting. This doesn’t happen to me very often.

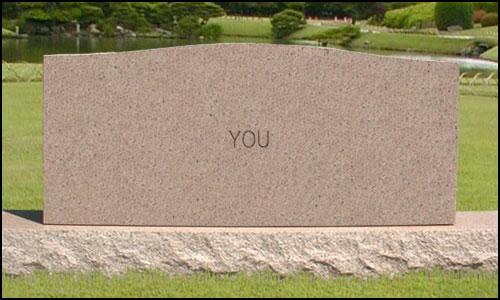

The text is 30 short essays, crafted as epitaphs, each one unfolding in a single sentence. On reading this idea, I thought, “That seems a bit much. That might be gimmicky.”

It actually works. Why?

The epitaph concept (a sort of “appropriated form”—a type of structure I’m into lately) adds many echoes, many layers, many possibilities. We arrive immediately on significant terrain—death. And a summary of life. We enter a mood of meditation, of introspection, not so unlike a walk through a cemetery (30 headstones aligned). And what is an epitaph on a headstone? First, a lie (actual epitaphs are 99% abstract and pithy and positive), but then instantly an absurdity (the measuring up, in a few words, on a stone). But, if you twist the epitaph (one concept of appropriated form work is to make it your own, to take the original—whether a complaint letter, Facebook post, list, whatever—and morph the form to your unique intent and way and need, etc.), lengthen the epitaph, broaden the epitaph into a lyrical remembering, the form can open us up to questionings. It can even lead us to ask, “What is life?”

The one sentence works, too.

It propels us. Some of this is Vollmer’s prose (not every one sentence is going to unspool smoothly forward; his do), a mix of crisp images, vivid objects, and precise, active verbs. Most every essay is narrative, but always poetic. And always they move: “…the gurgling and the wobbling whistles and the static and the rumblings and the droning undercurrents and the bellowing and the wind-like screeches and the faint lonely ringings and the moan of what sounded to the deceased like lost human voices…”

I wondered about Matthew Vollmer’s research into headstones. Each essay begins with an expected phrase (then peels off into something unexpected, as I’ve noted), “rest in peace,” “here lies a man,” “oh sleep in eternal rest,” etc. I wondered if he walked cemeteries for phrases, or if he looked online. If he looked online, it would be delicious, because the narrator within the book would certainly look online and then feel regret about looking online, as opposed to visiting a cemetery. I’m saying this narrator is very contemporary. He can’t just live. He has to examine the lived life, and reexamine. He has to watch himself. He has to analyze. He has the curse of the Modern Man, and he knows it, but he’s trying. He’s trying.

There are a lot of ghosts and a lot of angels, as seems appropriate. I wrote RELIGION DRENCHED on some page. (I would go look up the page, but I am sometimes lazy.) There’s a whiff of Flannery O’Connor, though not the moralizing she’s prone to. More a wrestling, a questioning. There is a struggle between religious ideas of life, and life as it exists, much more intangible than a taught order. There is a joy in finding moments that supersede any possible religious understandings of life and death.

There is a funny comparison of Larry Bird to Michael Jordan.

There is humor throughout.

And wistfulness. (Oddly, I almost caught a Brautigan feel at times.)

I kept thinking the idea of epitaphs was going to force Vollmer into situations he had better avoid: overly didactic material, syrupy material, or some attempt at philosophy. But this rarely every happened. We get scenes, not lessons. The philosophy is all over, but inherent to the form, and use of the narrative, the clear vignettes, the juxtapositions of nature and our contemporary lives, of generations viewing a moving target, the world, that day, Time. I mean one of my main takes after finishing the book was “How did he pull that off?” OK, In XVII, he gets a tiny bit preachy/ranty, but it’s amazing to me that the majority of these “Inscriptions” bring meaning through ordinary moments. The epitaphs track glimpses of a life (childhood to middle age) held up for observation (and reflection). A sort of wonderful machine that’s built here, a transmutation: a shoplifting child made me consider free will; a basketball game made me think about what links and un-links us as humans; taking a walk made me think about self-destructive tendencies; taking a kid to a library made me think about selfishness; teaching a college class made me think about the permanent stain of regret. Each piece made me set the book down for a minute and contemplate. That’s pretty impressive.

Honestly (and amazingly), only one essay fell short of the others, the final epitaph. It very much seemed like an essay wherein the publisher (or some misguided soul), said, “Hey, you should write an essay to end the book.” The others seemed much more natural/organic to the larger form.

There is nostalgia for childhood, an underlying tension about everything leaking away.

There is doubt, but hope (for example, the child eventually grows to have his own).

There is some acceptance, but mostly rage. Rage might be strongly put. No, I think it’s rage, just controlled, a hot fire made well. But not bitterness. The tone wasn’t bitter. It was sort of like “Why? Why?” as you watch leaves fall. It wasn’t “Why, you motherfucker!” as you cut down a tree with a chainsaw. That doesn’t make much sense, sorry. I’m trying to capture with my words what is most likely impossible to get across, the nature of the tone, possibly I am dancing about architecture, etc.

There is disbelief and belief.

There is a lot of worry.

here lies a man who often worried that he was not spending enough time with his son, that instead of engaging in backyard penalty shootoutsor teaching him how to play the theme to Star Wars on the piano or illustrating how to properly reinforce his Lego starships so they wouldn’t crack apart the minute anybody picked them up, he spent far too much time in front of his computer and phone, tinkering with words, reading and commenting upon his students’ papers, taking breaks to check scores and read e-mails and log onto a virtual dashboard that allowed him to scroll past the stream of images posted by all the blogs he followed, swiping the mouse pad and positioning the arrow on a valentine-shaped heart and clicking it whenever he liked a particular photo…

and

here lies a man who as a boy would follow his father into the woods and worry that he would be left behind because what if his father wasn’t actually his father but an android or a highly sophisticated robot or even a sort of shapeshifting alien which of course he was not or so the son figured even though sometimes the idea took hold so fiercely that the boy became nearly paralyzed with fear for they were so deep in the woods and so far away from home and of course he couldn’t share this information slash fear with his alien father who moved quickly through the trees often allowing limbs to slap backwards and hit the boy in his face because…

There are no periods on these epitaphs. Are there period on actual epitaphs? I don’t think so. What if there were?

To be alive you must be aware of your demise. To be alive you must be unaware of your demise. You must remember and forget. Impossible. But you must try.

I’ll end by saying there is a lot of sadness here, but the type of sadness to make you feel a little bit more alive. Or as I wrote in shaky black letters on page 98: EXHILARATINGLY MELANCHOLY. I have much more I want to say but I need to go run, far. And actually such a book makes me want to run, to move my flesh and bones while I got them. So.

Tags: Inscriptions for Headstones, Matthew Vollmer

Thank you for a great review and for the excerpts. Matthew Vollmer is a true visionary.

The earliest writing was writing on stone.

Thank you for sharing. This is an excellent review.

SunCityGranite.com

http://tinyurl.com/8b5k9l3

.

Granite Vases

The inscriptions engraved on Headstones tell more

information of a person’s life story. They will also tell wishes, likes and

dislikes of who sleep in eternal rest.

http://www.granitememorial.in/granite-vases.htm

[…] you don’t believe us, you can read a review of Vollmer’s book here, or an excerpt here. See? We like the book so much we’re willing to link to Hobart; every now […]