Author Spotlight

On Violence & Red Tales: An Interview with Susana Medina

I met Susana Medina at the inaugural reading of Book Works’ Semina series in June 2008. Her struggle with deafness and affection for Borges made her immediately endearing. Between shots of whisky and glasses of Haut-Medoc, we talked. Chitchat mainly about films and books, but somehow the talk became serious and autobiographical.

Born of a Spanish father and a German mother of Czech origin, she grew up in Valencia, Spain. Her short film Bunuel’s Philosophical Toys, deconstructs the instances of fetishism in the films of Luis Bunuel. Over the years I’ve come to believe that the gap between what Medina has accomplished in her doctoral thesis on Borges, and what her mainstream colleagues have passed off as literary theory, exposes academic discourse for what it is — an imaginary labyrinth without beginning or end that presupposes its own epistemological superiority.

This interview, started March 2011, has been in the making for nearly two years. I spoke with Susana off and on via Facebook.

***

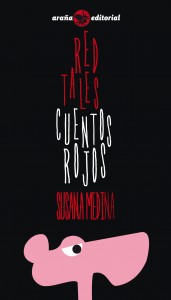

Maxi Kim: Stewart Home recently described your new book RED TALES as “a total shock to mummy porn fans – E. L. James meets J. G. Ballard! Makes both writing and BDSM dangerous once again.” I personally found it much more readable and theoretically latent than much of what passes today for Feminist writing, much more so than even Kate Zambreno’s Heroines. How did this project come to be? What are its origins?

Maxi Kim: Stewart Home recently described your new book RED TALES as “a total shock to mummy porn fans – E. L. James meets J. G. Ballard! Makes both writing and BDSM dangerous once again.” I personally found it much more readable and theoretically latent than much of what passes today for Feminist writing, much more so than even Kate Zambreno’s Heroines. How did this project come to be? What are its origins?

Susana Medina: I like your way of putting it, ‘theoretically latent.’ Red Tales came about through a cluster of concerns. I was interested in fluid sexualities, gender, androgyny, the irrational, compulsions. All the stories are narrated by wayward female narrators. To articulate a defiant female gaze was important for me. In a way, looking at the female nude in Art History, made me want to make all these women speak back. So maybe I became a ventriloquist for these sensual women who seemed so quiet. It was also a reconciliation with narrative, as my first novel, a fragmentary anti-novel, had as its point of departure the most minimalist Beckett. My interest in poetic fragments remained and I intertwined it with fast-moving narrative, so I suppose there is this newly found pleasure in narrative, with the fragment as counterpoint and vessel for interiority, as well as for the fragmentary realities we live. All the stories are conceived as spaces, like art installations. The image was central to all the narratives. I was really interested in American female artists like Cindy Sherman, Jenny Holzer, Kruger, the vanished Cady Noland, in subjectivity and identity as fluid entities… Thank you about the Kate Zambreno’s Heroines reference, which I googled straight away. Like I googled E.L. James when I came across Stewart Home’s blurb, which I thought was nicely confusing. By the way, I hadn’t read JG Ballard at the time –he was later to become one of my favourite writers-, but the connection is there, in terms of a shared interest in the psychopathology of everyday life.

MK: What do you make of Marie Calloway?

SM: I don’t know her. Who is she? Interesting?

MK: Interesting? It depends on who you ask. Like you, she’s interested in fluid sexualities, gender, compulsions, articulating something that approaches a defiant female gaze. She has put out public nude photos of herself with texts that overlap; there may be a parallel here with your project of looking at the female nude in Art History. I am reminded of that last scene in Lars von Trier’s Antichrist (2009) when all the wayward anonymous females climb up the hill to presumably kill Willem Dafoe.

SM: Googled her and printed an article, but still haven’t quite woken up. She sounds interesting, like Chris Kraus. You’ve worked with her, haven’t you? Or related? Cousins?

MK: Marie Calloway first caught my attention when I heard she was a North Korean writer interested in Marxism. She was up for working with Chris, but unfortunately Semiotexte wasn’t hiring. But back to you – as you know, I’m a big fan of the various texts on your website www.susanamedina.net. In particular, with everything that’s going on in Japan [the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami], I was drawn to your essay, “Listening to Marco Polo.” In that essay you talk about the “many types and degrees of violence, social, personal, visible, invisible, kind, brutal, professional, a grid of violence breaks the world into a myriad of splinters.” Do you have any thoughts on natural violence, or what Slavoj Zizek calls divine violence?

SM: When Zizek speaks about ‘divine violence,’ he’s speaking about a pure violence that serves no purpose except as a pure expression of opposition to injustice in the world. A tsunami is not violence of dissent. Natural violence just is, just as much as natural harmony just is. Natural violence is a reminder that we’re part of a process of creation and destruction. You can’t project any moral values on the inherent violence of nature. Nor justify human violence as mere mirroring the violence of nature. As human beings, we can decide whether to act violently or not, whether to add to all the shit or not.

MK: How has your perspective on violence changed over the years?

SM: In my early writing and readings I was more interested in our capacity for cruelty and violence. It’s much more difficult to write an ode to peace, than it is to mirror the violence of the world. Violence and peace, they’re both realities and fantasies. Fantasy and reality are interconnected. Ideas, imagination, text, are interwoven with reality and create new realities. Global harmony might be a necessary fantasy, maybe we have to play at being deluded gods while being conscious of the fallacy. When you’re surrounded by nihilism and cynicism, you have to x-ray where this leads you to. There’s truth and humour in nihilism, but you also need to know where the emergency exits are. Too much nihilism and you might as well commit suicide or do nothing, because nothing will never change. You have to find a constructive kind of nihilism. Maybe you have to fantasise about global harmony, in order to achieve a small space where something resembling fairness prevails.

MK: I enjoyed that essay on your website, “Tlön: a cosmology, an imaginary planet and the literary as virtual space.” As I was reading it I was reminded of a remark from Christian Bok’s Pataphysics: “Borges in Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius imagines an allegory about the seductions of simulation. A secret cabal of rebel artists has conspired to replace the actual world, piece by piece, with a virtual world, so that the inertia of a true history vanishes, phase by phase, into the amnesia of a false memory.” Do you see yourself as a rebel artist?

SM: (Hearty laughter) Yes, I suppose there’s a rebellious impulse behind some of the things that I do. Humour resonates throughout the history of philosophical idealism. Borges was highly tuned into this kind of humour. But you can also read “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius” as a story about how history is constructed by a minority through texts, hype, the gradual replacement of one reality by another. And right now we’re witnessing a conspiracy, with which we’re partly complicit, to replace tangible reality by a virtual world where we have become fantastic avatars with amazingly interesting stories to tell and virtuality is socialling us out.

MK: And how does your work cope with this virtuality?

SM: It doesn’t… I switch off the modem, sometimes… Going back to rebellion, there are far too many things to rebel against, too many received ideas or patterns, not worth repeating. I’m interested in innovation, in exploring unknown areas, rather than in conventional narrative realism or formulaic writing or bland ways of writing that have been done to death, to the extent that they all become an amorphous mass of dull and interchangeable printed matter. When I started writing, I was interested in doing works that couldn’t be easily classified as belonging to one genre or another. I was extremely interested in hybridity, in the gaps between the genres and media.

MK: Is the belief in utopia always naive?

SM: ‘Utopia’ is a beautiful word but we should come up with another word that doesn’t have a negative connotation from its very first letter: ‘U’ from the Greek ‘ou,’ means ‘not, no.’ Utopia literally means ‘no place,’ so it already has sheer impossibility inscribed in its prefix. The history of utopia is incredibly interesting. I have an aphorism that probably answers your question. It’s in a section of aphorisms called ‘Medinations’ in my book Souvenirs from the Accident: ‘If everyone went on strike for humanity… for a return to the ideal of humanity. If the idea of humanity is a myth, a lie man told himself and he became dazed with such a fragrant lie, pretty as a cosmic illusion, it’s because there is something truthful in the utopian impulse.’

MK: We have to be truthful to that impulse, if it’s within us?

SM: If by ‘utopian’ you mean ‘egalitarian’, I don’t think it’s naïve to strive towards a more egalitarian society. It’s utterly and absolutely necessary. It’s vital to be always planting seeds for a fairer society and I think you have to begin by the smallest of acts, your interpersonal relationships and by knowing yourself. I have this idea that you can think in micros and then slowly enlarge them. Create micro-utopias, see if they become infectious, like laughter. But Maxi, what do you think about believing in utopia? And the effectiveness of civil disobedience?

MK: I’m quite naive. I think utopia will re-emerge as the future technological singularity, in the next 30 years or so, not only reintroduces us to the Idea of A.I. — but perhaps more importantly the Idea of Communism. In terms of civil disobedience, I think what’s going on in Egypt [the Arab Spring] at the moment is quite inspiring; like South Korea 20-30 years ago, Egyptians are really having to do a lot of soul searching: What does Egypt want? How will Egypt survive and thrive in the new world order? What will the role of secular culture and Art be in this new Egypt? So much has occurred in the last few months: political upheaval everywhere. Any thoughts on the current path we’re on? Are we reaching a tipping point?

SM: I look forward to revolutions that overhaul misogyny. We’ve always been reaching a tipping point, it’s a question of degree. I think the difference now is the internet and social media where we’re updated about all the conflicts in the world from the grassroots. But I think there should be more upheaval in the West. We’ve just been subjected to one of the biggest robberies in history: the banker’s bailout. Given the gravity of the situation, there should be more social unrest than there is. We are witnessing the Arab Spring and on the other hand, social inequality is reaching almost Victorian levels in countries like the UK.

As to utopia and A.I … Do you mean that if we had the right brain chips we could reach an egalitarian society? An anti-greed chip, an empathy chip, an anti-stupidity chip, an anti-power-hungry chip? The human brain is the most complex known biological structure. Technology is competing with thousands of years of evolution. Technology can be amazing, but tends to lack nuance, in some ways it can be like a savant, able to process large quantity of data, but unable to read a gesture, to caress the detail.

MK: I’m inclined to agree with you. The human brain is, indeed, the most complex known biological structure, which, is precisely why I believe humanity will successfully reverse engineer the human brain. Already we have rapidly accumulated data on the precise characteristics of the constituent parts of the brain, ranging from individual synapses to large regions such as the cerebellum, which comprises more than half of the brain’s neurons. As futurist Ray Kurzweil reminds us, “Extensive databases are methodically cataloguing our exponentially growing knowledge of the brain. Researchers have also shown they can rapidly understand and apply this information by building models and working simulations. These simulations of brain regions are based on the mathematical principles of complexity theory and chaotic computing and are already providing results that closely match experiments performed on actual human and animal brains.” Research in this area is so new I think it would be fatally premature to say what is and isn’t yet possible with A.I. Though I share your sentiments on technology’s general dumbness and stupidity, we ought not make any concessions concerning the viability of a future singularity; it would be like giving up on the Human Genome Project in the 1980s – when the goal of sequencing and identifying all three billion chemical units in the human genetic instruction seemed technically insurmountable.

SM: Don’t get me wrong, I’m in awe of technology and artificial intelligence. It’s just that from the little I know about Ray Kurzweil’s ideas, he was talking about thirty years for the emergence of a greater than human intelligence. That’s where I’d become a little skeptical. The human brain runs on conflict. You talk about chaotic computing … To come up with the technology that mimics the chaos and sophistication of the brain, I’m sure that’s going to take a while. Besides, there are many types of intelligence. How would existential superintelligence come about? But who knows where we’ll be in thirty years’ time? The internet has happened pretty rapidly. It has utterly transformed our horizons.

MK: I’ve read that you’re currently working on Spinning Days of Night, which has been awarded a substantial Arts Council Writing Grant. Is this a novel that you’re working on? What stage is the project in?

SM: Spinning Days of Night partly touches on how awe-inspiring technology is. The main character becomes a cyborg, a bionic woman. She wears a cochlear implant, so I’m touching on the subject of medical cyborgs. I’m a bionic woman, I’m a cyborg. The novel is based on my own experience of becoming profoundly deaf and being implanted. That’s the main reason why I’m so fascinated with technology. To think that I lost all my hearing and I have a chip implanted in my skull that allows me to hear, that I have a computer-brain interface, that’s pretty thrilling. But, it’s also why, no matter how awesome technology is, I also have a first-hand idea as to its limitations and how amazing we are. The initial research for cochlear implants started in the 1930s. They became commercially available in the early 70s. But I’d say it was in the 90s, when they became widely available. It’s an amazing piece of technology. And yet, they’re still to come up with a noise-reduction algorithm, for instance. The human ear distinguishes between what it wants to hear and what it doesn’t want to hear. It does so automatically, getting rid of background noise in nano-seconds. In some ways, machines surpass us in logical-mathematical intelligence, in other ways they don’t. The algorithms in nature are awesome.

MK: Is your novel a venture into science fiction?

SM: I’m writing about chance, chaos, silence, sound, trauma, shadows, becoming a cyborg. Each piece of writing of mine tends to be rather different from the previous one. I’d like this novel to be a slight parody of Science Fiction cyborgs, as they’re presented as superhuman, because at present the only ‘literal’ cyborgs we know, are medical cyborgs and that’s quite a different reality. But I still don’t know many things about my novel, how it’s going to hang. I’ve no idea at which stage of the novel I am at, as I’m working on it intermittently, in-between other projects. I suppose I’m almost half-way through. I have 500 pages worth of notes or more, a real writing labyrinth. It’s tempting to press the delete button. It’s a real labour of love, and patience, working at a snail’s pace, diametrically opposed to how fast things happen today. Changing the subject slightly… Good news Ai Wei Wei and others have been released. Even if silenced. You’re about to publish this book on North Korean art. Is censorship something you touch upon? And if so, how different is it, from Western censorship?

MK: Yes, censorship has to do with a big chunk of my North Korea book. Of course, censorship in Korea is much more direct and totalitarian in the classical sense. I know certain of my friends who would argue that the Western media too is “totalitarian” — but there really is no comparison. The way that the West filters and manipulates the news is nothing like how Kim Jong Il has created his own state news outlet with accompanying forms of aesthetic coercion in the form of posters, paintings, movies, television programs, music, etc, etc. Totalitarianism in North Korea is indeed total. On a tangential note, what did you make of the 2011 London riots? As soon as I saw the pictures of black youths confronting the police, I thought back to the Los Angeles Rodney King riots.

SM: Fortunately, it was rather different from the Los Angeles Rodney King riots, since 53 people died during those riots and thousands more were injured. By contrast, five died in the London riots. It’s to do with a fundamental difference in gun politics. There is a lot of resentment on the part of black youths towards the police, since they’re fed up of being stopped and searched, but the London riots were a party where all races hung out. It seems that three quarters of those convicted already had criminal records. It was a hooligan party, and some bystanders got caught in the looting euphoria. Hardly anybody is going to bat an eyelid when big corporations are looted, but when small shops are ransacked and burned, when neighbour’s cars are set on fire and innocent people are actually mugged (cameras, laptops, mobile phones) and beaten up as part of the big hooligan party, well, then, it’s clear there is a spirit of undiscriminating hatred, a severe dislocation that echoes the ruthless psychopathy of capitalism.

MK: Psychopathy of capitalism, I like that. It’s preferable to terms like “risk capitalism” or “zombie capitalism” What are the exact symptoms of this psychopathy?

SM: We have a society where 10% of the population has 273 times more money than the remaining 90%. The socio-historical soup in which the London riots happened is a soup made out of moral, political and financial collapse. During the last two years, all the major institutions in England (because these things are not happening in Scotland, Wales or Northern Ireland, the latter being another story) have collapsed. This is the socio-historical soup in this country at present: rescuing the banks when they’re responsible for the financial crisis and continue to give themselves bewildering bonuses and privileges; the expenses scandal that saw how MPs enthusiastically abused legal loopholes to line their pockets with tax-payers money; tax evasion of billions of pounds on the part of the guy responsible for advising on cuts to public services which are going to affect the poorest; a Prime Minister’s communications adviser who actually belongs to the Murdoch gang and is steeped in murk; dodgy senior executives with a soft spot for accepting backhanders at the top of the Metropolitan police/ Scotland Yard; a cabinet responsible for austerity measures, which is referred to as the millionaire’s club: 80% are millionaires… Not to mention the illegal war in Iraq started by the previous government…

MK: The terms Feudalism and Neo-Medievalism comes to mind.

SM: There is this very useful word: Kleptocracy. It is usually applied to Third World countries. But one can see how it’s a model for some Western elites. It means ‘rule by thieves’ and is a form of political and government corruption where the government exists to increase the personal wealth and political power of its officials and the ruling class at the expense of the wider population, often without pretence of honest service. Feral capitalism breeds Plasma TV riots… The rioters whose sole undiscriminating motive was greed are the other side of the coin of our corrupt ruling elites. The sentences rioters received are often disproportionate. Double standards rule the waves. The ruling elites here make the laws in such a way, that a politician buying luxury goods with tax payers money (a second-home to be used by one of their relatives, a £8000 Plasma TV, a ducks pond) might not be prosecuted, whilst a guy stealing £3.60 worth of bottled water in the mist of the riots actually goes to prison for six months.

***

Maxi Kim is a literacy advocate with USC’s Rossier School of Education.

Susana Medina has published a number of essays on literature, art, cinema and photography, curated various international art shows, written art catalogues, exhibited at Tate Modern and collaborated with several artists. Her mixed media work can be found scattered on the internet.

Tags: Maxi Kim, red tales, Susana Medina

Why is it necessary to criticize Kate Zambreno in order to praise Susana Medina?

“I personally found it much more readable and theoretically latent than

much of what passes today for Feminist writing, much more so than even

Kate Zambreno’s Heroines.”

I didn’t read that as a criticism. I understood the sentence to mean: most of what passes for feminist writing today is not very readable or theoretically latent; Kate Zambreno’s Heroines is better than most (re: readability and theoretical latency), but your book is even better than Zambreno’s book. If anything, it’s a compliment of Zambreno’s book.

I see that. I just think this thing of establishing the quality of a female artists against the lesser quality of another female artist is a tic that reappears far too often in reviews.

[…] Lo autobiográfico da un salto a lo ficticio. Estoy escribiendo sobre el azar, el caos, el silencio, el sonido, el trauma, las sombras, sobre convertirse en un ciborg. Cada uno de mis proyectos de escritura suele ser diferente de los anteriores. Me gustaría que esta novela fuese una ligera parodia de los ciborgs de ciencia ficción, ya que nos los suelen presentar como superhumanos, porque actualmente los únicos ciborgs de verdad que conocemos son los ciborgs médicos y eso es una realidad diferente. Para los que leéis en inglés, el primer capítulo de Spinning Days of Night lo publiqué en The White Review, una revista inglesa en papel y electrónica que está muy bien. Y hablo más sobre mi interés en la tecnología en una entrevista reciente en HTMLGIANT. […]