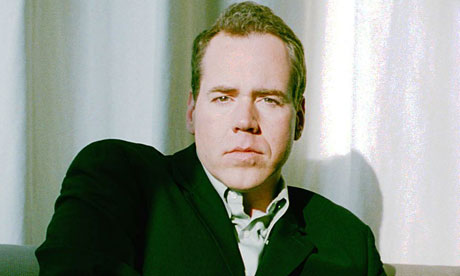

Author Spotlight

The Humanity in Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho

1. I avoided American Psycho for as long as possible before picking it up. I hadn’t even realized it’s about to celebrate its 20th birthday (jesus christ) until I was about halfway through my first and only read at last last week, which went down from cover to cover in two evenings. It’s the first time in I don’t know how long that I’ve been compelled to carry a book around with me and read it wherever I am, instead of doing other things, such as on a Friday night on my sofa in my underwear, wanting to stay inside it, even as in many ways the book keeps repeating itself, its elements; there felt something there.

2. I think I hadn’t read the book, and in fact talked shit about it not having read it, all this time because of a series of false expectations placed upon it. I’m certainly one of the last you’d call a squeamish reader, in fact often the more brutal the better, but something about the mythology of Ellis, and the weird taste I’d gotten in Less Than Zero, the only book of his I’d picked up until this year, which reflected to me at the time a kind of retarded field of vision I wasn’t really interested in: drugs, and fucking (which, I know, that’s supposed to be what you want, but that’s part of what made it not at all what I want: it seemed obvious). I chalked American Psycho, too, even among all its hype, to the same kind of thinking: that this couldn’t really be that big of a deal, that it was just some guy getting his balls off writing out some not even that hardcore (in language) action, and etc. etc.

3. Then on a whim, at the end of last year, I picked up Lunar Park. I think maybe I’d peeked in the front pages a few times to see what was up with it, as it was murmured to be meta, and how would that work on him; the first few pages seemed intriguing but I still wasn’t sold, and still anyway I ended up with a copy of it from a used store randomly, and it still sat on my shelf for a long while. At some point I asked Dennis Cooper what he thought of that one in particular and he said he’d loved it, and trusting Dennis’s taste for such, why not give it a try? On finally actually reading I found the book really fantastic on several levels, particularly the opening sections about his career and the way it had come to move around inside his life in ways he could not even really control; particularly, too, in being haunted by the Patrick Bateman character, who shows up in Lunar Park to fuck with Ellis directly, which causes some really interesting repercussion as to what it is to create, and so on. More so, through Ellis’s franker discussion of how the character had been based at least in part on his father, and his relationship with his father, and the bottling up of a kind of anger and terror in the midst of that and his life, it seemed like there was something much deeper, personal to the construct, something I’d maybe overlooked about him, and so on that note, a couple days ago I went and got a copy of AP to see what was up at last for myself.

4. The most immediate thing that struck me is that American Psycho is frequently hilarious. I think being funny on paper is a really tough feat, and even when something is funny it might not necessarily be laugh out loud funny, but the nature of the humor here isn’t really based on jokes or even posturing: it is inherent in the logic of the book. For the entire first third almost nothing of the murderous reputation of the book occurs; instead we’re fueled entirely by the presentation of self of Bateman as he deals with his high end acquaintances and coworkers, running through a similar gamut of illustrious degradation one might have expected given Ellis’s career and prior work. What comes out of this, though, and this is something I had sort of expected from the movie, but not quite with such flawless tone, is a building pathos in Bateman’s brain. This isn’t necessarily a murderous man, or even a nihilist of sorts, completely blank, but instead he is somebody who wants. His wants might be based on front end with the flanking references to superficial crap, as shown in the incessant descriptions of what everyone is wearing by their brands, and the wish for impressing others with such and impressing himself with gaining more; but really it is in the way he is continually shunted off from conversation, saying things that no one hears, no matter how plainly stated, the continually being referred to by the wrong name, the back and forth trading of lovers like items, etc. Though Bateman may play ball, and clearly is central to this lifestyle, there is something in the current of him that tells you this isn’t where he wished to be, not really; that even as he spouts the same junk as any other, and with even more fervent dedication pursues those items that others idolize, there is something in here that is, almost against his will, becoming derailed. As the book continues this pressure cooker of want versus appearance will continue to build and fold over on itself in such a way that even as the blank speech repeats and repeats, it continues to take on new levels of pathos in each iteration, causing in the wake of itself, a field where between the lines almost anything can, and will, happen.

5. The way that Bateman copes with the building distortion between his inner want, however buried, and the continuing nothing his life has filled with is to break with himself underneath himself and do violence. The book goes on building further and further levels of intricately imagined scenes of rape and torture, which late into the book begin to take on a kind of ingenuity otherwise absent from his life. All throughout this, Bateman famously maintains for the most part the same copy-voice he uses in making dinner reservations or trying to impress women he wants to fuck. The narration’s sheen is perhaps what most upset readers of American Psycho early on, in that such acts were being put on with such apparent detachment that the book was “violence for violence’s sake,” which while I personally don’t have trouble with, I don’t think is the case at all here. This is not a book, as has been claimed, that sees the dark of the world and wallows in it. This is a book that in some way wanted more. This is true for Bateman, I think, as a character, if one that never definitely admits it, or changes, though there are certainly moments where the sheen begins to crack, if not in the face of it itself, but in the face behind the face: Bateman visiting his mother in a home and his odd silence there, while still not emotional; his weeping at sitcoms on TV; and even in the exuberant tone he takes describing pop music, which is of course written in a brilliant flat and media-inherited way, but also, in its reiteration, to me reflects not nihilism, but an even deeper burning for there to be something good in the world; something perhaps misplaced but to Bateman joyful, even in the multi-cloaked levels of how blank to some something like Huey Lewis, for instance, is. His wanting, where it lands, seems stilted, misplaced, but that doesn’t make it any less sincere, even when deployed as a passage turned from murdering women violently; in fact, it’s more poignant that way, if you ask me. There seems to be a big idea in literature and even all of entertainment that for something to show heart, be heartfelt, it must have light; that the moments must exhibit some kind of “human element” in order to make it relatable, and therefore somehow validated. This was Wallace’s big problem with this book, and it’s something you hear a lot. I’ll argue, though, that by leaving that sheen up, by complicating the borderline redemptive qualities of Bateman, and feeding his only out into a pathos that is terrifying in its operation in hurting other humans, is actually even more human, more honest; it does not have to bare itself in order to realize where it is. If one’s belief in humanity is founded on the idea of love, then why is that the element we continue to question? Do we really need to reach a moment in every work to remember light and love to know it exists? That the job requires you coming back to this by default seems to me a weaker pose than knowing already it is in there, or can be, and what of it. Depending on that requirement seems cheaper in spite of itself, actually less human, and less sure of the human than one who assumes it, or, holy shit, on paper, lets it go.

5. The way that Bateman copes with the building distortion between his inner want, however buried, and the continuing nothing his life has filled with is to break with himself underneath himself and do violence. The book goes on building further and further levels of intricately imagined scenes of rape and torture, which late into the book begin to take on a kind of ingenuity otherwise absent from his life. All throughout this, Bateman famously maintains for the most part the same copy-voice he uses in making dinner reservations or trying to impress women he wants to fuck. The narration’s sheen is perhaps what most upset readers of American Psycho early on, in that such acts were being put on with such apparent detachment that the book was “violence for violence’s sake,” which while I personally don’t have trouble with, I don’t think is the case at all here. This is not a book, as has been claimed, that sees the dark of the world and wallows in it. This is a book that in some way wanted more. This is true for Bateman, I think, as a character, if one that never definitely admits it, or changes, though there are certainly moments where the sheen begins to crack, if not in the face of it itself, but in the face behind the face: Bateman visiting his mother in a home and his odd silence there, while still not emotional; his weeping at sitcoms on TV; and even in the exuberant tone he takes describing pop music, which is of course written in a brilliant flat and media-inherited way, but also, in its reiteration, to me reflects not nihilism, but an even deeper burning for there to be something good in the world; something perhaps misplaced but to Bateman joyful, even in the multi-cloaked levels of how blank to some something like Huey Lewis, for instance, is. His wanting, where it lands, seems stilted, misplaced, but that doesn’t make it any less sincere, even when deployed as a passage turned from murdering women violently; in fact, it’s more poignant that way, if you ask me. There seems to be a big idea in literature and even all of entertainment that for something to show heart, be heartfelt, it must have light; that the moments must exhibit some kind of “human element” in order to make it relatable, and therefore somehow validated. This was Wallace’s big problem with this book, and it’s something you hear a lot. I’ll argue, though, that by leaving that sheen up, by complicating the borderline redemptive qualities of Bateman, and feeding his only out into a pathos that is terrifying in its operation in hurting other humans, is actually even more human, more honest; it does not have to bare itself in order to realize where it is. If one’s belief in humanity is founded on the idea of love, then why is that the element we continue to question? Do we really need to reach a moment in every work to remember light and love to know it exists? That the job requires you coming back to this by default seems to me a weaker pose than knowing already it is in there, or can be, and what of it. Depending on that requirement seems cheaper in spite of itself, actually less human, and less sure of the human than one who assumes it, or, holy shit, on paper, lets it go.

6. One could argue, as well, that there is also value in a book not having any redemptive qualities whatsoever, that that is human too (and I’d agree), but that’s not really true in American Psycho; this book is bleeding, begging. Its shit-eating grin has been soldered to its face. Even as the want seems insane, sad, all over, to insist or claim one’s wants pertain only to the true and good seem triply fucked. I don’t particularly care about fashion or expensive stuff, but I laughed and kind of totally nodded in agreement when in the middle of listening to other people go on about dinner reservations, Bateman’s monologue blinks out somewhere else: “J&B I am thinking. Glass of J&B in my right hand I am thinking. Hand I am thinking. Charivari. Shirt from Charivari. Fusilli I am thinking. Jami Gertz I am thinking. I would like to fuck Jamie Gertz I am thinking. Porsche 911. A sharpei I am thinking. I would like to own a sharpei. I am twenty-six years old I am thinking. I will be twenty-seven next year. A Valium. I would like a Valium. No, two Valium I am thinking. Cellular phone I am thinking.” I’m sorry, that is real to me, in a realer way; that is the way more frequently than not it feels to be inside, to me, a head, if about other things that what my head is, and sometimes not even. That American Psycho is so heavily criticized for its supposed lack of feeling to me seems even more of a fuckhole than the decapitations or the rape. What has been raped is our ability to see things without demands laid on them, our own demands. In some ways those bearing these kinds of criticisms aren’t really listening in the same way no one is listening to Bateman when he tries to confess to what he plans to do, though in this case in semantic reverse, for the opposite reasons: to bury the thing alive. When a book is read as if we, the reader, are its receiver, instead of the book receiving us, that’s how the function of art is slowly, over time, destroyed.

7. More than Bateman’s path, though, this book seems to me about the creator. The parts where I felt most electrified by American Psycho weren’t the murders, but the opening of the blank between. It seems really clear to me that this book was made by someone who was dealing with a heavy existential fucking. And that doesn’t mean that the violence and pathos here is a direct result. This, in some way, is a weapon of fantasy; an expurgation of that terror of being in the world; of how being a human doesn’t necessarily underline itself. This weapon is not meant, I think, either to be aimed at us; it is aimed at something inside the creator, Ellis, to go head on into it, to milk it, to let it eat. That someone’s personal destruction comes out in the form of Bateman isn’t ill, and isn’t anti-human; it is actually, in how it bends back on itself, somehow more honest; not a parody or caricature, but becoming. This was made because someone needed to survive. Says Ellis: “[Bateman] was crazy the same way [I was]. He did not come out of me sitting down and wanting to write a grand sweeping indictment of yuppie culture. It initiated because my own isolation and alienation at a point in my life. I was living like Patrick Bateman. I was slipping into a consumerist kind of void that was supposed to give me confidence and make me feel good about myself but just made me feel worse and worse and worse about myself. That is where the tension of American Psycho came from. It wasn’t that I was going to make up this serial killer on Wall Street. High concept. Fantastic. It came from a much more personal place, and that’s something that I’ve only been admitting in the last year or so. I was so on the defensive because of the reaction to that book that I wasn’t able to talk about it on that level.”

8. To be honest, too, despite him being one of my biggest lights, I’ve always hated most of Wallace’s thinking and speaking about what he thought he was doing: his fiction for the great breadth of it is about as far from “being human” or the “applying CPR to the good parts” crap as I could imagine. A lot of Wallace’s fiction actually seems way more alien and fucked and actually darker than Ellis, in its own way, and that Wallace couldn’t see that about his work is part of what makes it interesting, his desire to try to rationalize it outside itself to these logical extensions is part of what makes the whole thing in itself that much more beautiful. Wallace’s grandstanding in this manner was always infuriating to me, and not to mention, in the case of Psycho, totally fucking wrong. I think I glossed over Ellis before on the same premise though w/o even having read more than Zero, and having read that when I was like a little self-righteous; I don’t think Ellis is just reflecting his surroundings; he’s letting something black inside him (and that he saw inside his father, as Lunar Park shows, if from another sort of angle) come out and take full bore and run amok in that bleak world, which to me is something most anyone is gripped by, regardless of how much they realize it or want to admit it; it’s super fucking freeing in a way, and if that’s not a “kind of CPR” then jesus what is. All those layers of Bateman’s thinking and various internalizations and then reactions to that bottlenecking, and ways of dealing with it without exploding (until he explodes); some of those passages, as they build, just reach these places that are way more demonstrative to me of an inner life, though he is so guarded and good at caking on those layers (which also, in being hilarious, does him no good for people who don’t accept humor as art, though to me it’s one of the hardest and most right on ways to eek some of these things out) that it’s really easy to say, “oh, he’s just being coy, or wallowing in it, or etc etc.” It’s a lazy reaction, and a really easy one to let happen to you; I definitely did, without even having read. I’m actually maybe glad now I’m finding it at this time in my life rather than years ago.

9. Beyond all this, or perhaps in light of it, American Psycho in some ways takes a lot of risks as literary art that became overshadowed by the sensationalism of the gore. People want gore; some want to have a reason not to want gore, so they saw this gore and some pretended to be shocked by it, and some flipped just to those sections of gore and read those and but the book down. In this way, the book got overlooked for what to me seems a lot of its best features. The voice here, and the weaving of its many repeated threads, such as the clothing descriptions, the subjects of The Patty Winters Show, Bateman’s internally spooling sense of humor in spite of himself, the weird meandering conversations about manners and reservations and hardbodies, etc., is kind of a wonder of narrative in itself, and certainly not something you’d see in a more “academic” kind of work. A big part of Ellis’s gift, and subsequently, his handicap in appearance, is that he is coming fully from himself, and where risks are taken they might be easily misperceived. Further structural formats expand our perspective even further, by what they do not do, such as the “clipping” of Bateman’s consciousness, where scenes suddenly shift from one paragraph to the next with things having happened in a period we can’t access because Bateman can’t access it, or won’t; or maybe it didn’t happen. Enough framework is suggested that all of this, somewhat like Ellis’s, could be a coping mechanism of an otherwise ineffectual person, taking power only in his mind. A passage near the very end, titled “End of the 1980s,” brings this same clipping into more spiritual direct kind of magnetizing of the polar ends of the want for love and want for destruction. Here we see Bateman faced with someone who could actually love him, his secretary Jean, perhaps the only character in the book not plagued with bullshit (and so of course in love with the deepest skew of them all), and as they talk about what life could be, confronting the idea of that love, Bateman’s brain continues to flex out, into “…where there was nature and earth, life and water, I saw a desert landscape that was unending, resembling some sort of crater, so devoid of reason and light and spirit that the mind could not grasp it on any sort of conscious level and if you came close the mind would reel backward, unable to take it in. It was a vision so clear and real and vital to me that in its purity it was almost abstract. This was what I could understand, this was how I lived my life, what I constructed my movement around, how I dealt with the tangible.”

10. In the end, this book refreshed me; I saw in here something I feel like as a supposed human I struggle with everyday, and not in a way that was made to be a cake for me or even a mirror for me, but a product like new skin, forced out because there it is. If more books had this type of aura, this willingness to shit straight out of the mind and blood for oneself, and with a craft that exists by force in an individual, I believe as readers and as humans we’d all be better off.

Tags: American Psycho, bret easton ellis

i was interested in this. thanks, blake.

This is absolutely great, Blake. I taught American Psycho last spring and hadn’t read it in a decade, and no one in the class had read it before, and come hell or high water it refreshed us all. The beautiful transition from comedy of manners to prolonged snippets of hell (or not transition as much as weaving) makes for such a satisfying narrative structure we unapologetically couldn’t get enough.

Thank you for this, Blake. Either most people I’ve encountered have never heard of Ellis, or think he’s just an asshole.

That excerpt in 9 sounds like some of the best parts in The Passion According to G.H., a book that is really similar, I’m realizing. Thanks for this.

I appreciate your thoughts here, Blake. American Psycho is one of my favorite books and when it was first released (and to a lesser extent now) it was misread by a lot of people who couldn’t ( or probably wouldn’t) think through the sensationalism. I was particularly interested in #7. It offers a different perspective in thinking about the book as an expression of isolation and alienation. I suspect many stories rise out of such feelings.

This is all right. I agree with so much of this. Having just read the book, I smiled at all of the references. Some things that you point out really help shed light on a few of the more subtle tricks in the book. I doubt that I’ll ever read his other novels, but I picked this up on a whim about a week ago, and was completely impressed and disturbed and happy with it, in a weird way.

Read American Psycho sometime last year, first book in a long time that I wish I had written. Agree with all you write here, would suggest in addition that the text must work better now when first written. The constant commodification of life and culture then being a semi-exclusive domain of the rich. Now we all live in Apple’s pocket, in a world deluged with faddish technology priced to own. Everyone blogs or tweets just like bateman about their favorite albums. Who woulda thunk it way back in 1991?

I read Less than Zero and Rules of Attraction in 2001 or 2002 and always meant to pick up American Psycho. I ended up seeing the movie and just thought “that’s good enough….I get it.” There is tremendous depth to Ellis, but the sex/drugs/violence camouflage it. It keeps the highfalutin away and the low-brow can’t see past it. Good piece Blake.

Reading this has FINALLY compelled me to click the Multnomah County Library tab up there and place the book on hold. Yet another book– but one which, for some reason or another, I’ve managed to avoid reading for several years though it has been recommended to me countless times. Thank you for this thoughtful entry, Blake, and for giving me the impetus to click further.

well, as a person he is a complete asshole, but that doesn’t mean he hasn’t written some killer books

“Frequently hilarious” — that’s what people miss, I think.

Might sound strange, as I don’t think they’ve got all that much in common (though I haven’t read anything by Ellis), but the end of 5 made me think about a lot of the things I’ve been thinking about about McCarthy’s Outer Dark. I liked that.

This makes me want to read AP.

There is less thinking in the (albeit brief) and stuttering dialogue from the text you post here than feeling, I think, which does make the book all too human, in the sense of, say, Nijinsky’s diary or the like. Have you read that? Apparently Adler worked with Nijinsky (a dancer) and tried to get him to “have hope”—possibly this would have been an interesting consequence if it had worked. Anyway, it’s an interesting read (albeit without the narrative that Ellis uses here) and is available from UC Press, I believe. But these notes are encouraging to me about giving the book a try, though my fiction library and reading have been wantingly slim lately.

I’m pretty sure this guy always sucked.

Wicked insightful response, Blake. Really enjoyed reading your thoughts on American Psycho, especially because as I’ve said here and elsewhere, I’m currently obsessed with the idea of humanity and its other: in/un/de/non-humanity in art, especially literature.

I got sidetracked the other day, but I wanted to respond to your snippet about Infinite Jest seeming like it were written by an alien who couldn’t figure out humans. Yes! I am currently in the middle of Rilke’s Notebooks of M. L. Brigge (a book I think you’d appreciate, if you haven’t already) and I get a similar feeling: that it’s an attempt by an alien to understand humans, but in Rilke’s case I’m not sure he fails at it.

Anyway, getting back to Ellis…

I think what you say at the end of #5 about the absence of light reinforcing humanity more than the presence of light is very striking. In addition (or perhaps to complicate things further), there exists a counter argument to those who seek to found thier idea of humanity on love — Zizek has made this claim — which is that love is evil or that love is a violent act. (This echoes a connection you make at the end of #9.)

Last thing I’ll mention is that I’m teaching Tao Lin’s Eeee this week — an experience I hope to write about and post here soon — and there are ways in which the Bateman monologue you mention in #6 seems to resonate with Andrew’s internal monologues: the randomness, the jumpiness, the non-sequitur, the repetition, the blasé. In fact, part of my lecture today dealt explicitly with how that mode of internal narration presented a “more real” representation of the workings of the mind than many other modes of stream-of-consciousness. The more I think about it, the more I see connections between Eeee and American Psycho…to bring it back to your point about American Psycho being criticized for its lack of feeling, there is, similarly, a kind of numbness from top to tail in Eeee. But whereas Bateman actually commits murders, Andrew only thinks about “killing rampages,” albeit obsessively.

This

– “When a book is read as if we, the reader, are its receiver, instead of

the book receiving us, that’s how the function of art is slowly, over time,

destroyed.” – is one of the most amazing sentences I’ve read this year. This

whole review was a model of what the form should be. Thanks so much for this

incredible review, Blake. I really like that you like it, that it was able to

turn your head on its neck. And that you get so much of what is left out of its

reception: I don’t know if I’ve read anything on AP that

synthesises so much of how I feel about its much-deserved massiveness as this. Despite

all the emphasis on its affectlessness, I don’t get how people can not see that

the book is so genuinely felt, a blood and sweat labour of

love (imagine the intensity of writing this thing: how can

people say it has no feeling?), and how that – not “disaffection” – is what makes it a truly milestone novel.

Before

you get to it, you can’t help but think that, with such a ‘high concept’ premise,

there’s only so much it could possibly do: serial killer on Wall Street

premise, cute, clever, essentially overstated, ready for its close-up and its

movie deal. No. The book caused such controversy, I’d say, before and on its

release, because its concept is not social satire at all: this book is realism,

plain and true. Not formally, I mean, but in content: it is totally a non-fiction

as only fiction can do it. Also, realism in that it takes itself 100%

seriously. And it is funny because of that: because it is so trapdoored

with incongruities and juxtapositions that are partake only of its utter hewing

to the plane of its reality. Like most comedy, though, it is also not funny

at all for many people, both today where it’s become this sober ‘moral

novel’ of eighties excess, but also especially back when it was first released,

as was evidenced by the baffled rage in the NY-oriented literary salon world,

who analogue the predations of Wall Street with their human cultural alibis

that patina the sadism of accumulative practice with the sentimental

mawkishness of being a human being, as well as the tabloid morality of media

muckrakers. On that point, it’s worth remembering that the hatred of this novel

was largely a confected controversy, a mix of government

censorship bureaus, risk-averse publishing circuits, astroturfed grassroots letter-writing

hysteria (death threats, etc.), literary ‘critics’ unhappy with the death of

the book this novel takes for granted to tell its most literary story, all dotted

by the occasional long-assimilated (and simultaneously indentured to be the

chosen targets of villification because it’s so damn easy) feminist talking

head against the book, like Gloria Steinem, who, mind you, were the only

feminists the media chose to spotlight, precisely because they were meant to

represent moral reaction, not feminism. (It’s no surprise to me that a woman

ended up eventually making the movie version, and brilliantly too.)

It severely disappoints me how acculturated Ellis has become today when he

talks about Psycho and its reception these days. Almost

invariably he makes some sneering anti-feminist remark (whether this is ‘how he

really feels’ or just controversy is a boring argument with Ellis-defenders and

besides the point, because it’s the very provocative narcissistic soundbiting

that is itself the biggest fail, with the recent casual misogyny only its

over-sugared frosting). You talk about hating how Wallace spoke of his own work

(me too: for starters, dude was far, far, far darker and against ideas of some

ultimate saving grace than he thought he was); that’s how I feel about Ellis,

especially now, after Imperial Bedrooms, which is a strong

contender for the worst book I feel I’ve read in the last five years. That

sounds like a big statement but I’ve thought long and hard about its fatuity as

a creation and it deserves the diss. (Though I’d be very interested to know

what you thought of it, of course.) Particularly, there’s always been an

undertow in Ellis of a half-baked “becoming who you are” idea on the

relation between celebrity and biography, the Horatio Alger Ellis, delineated

by a pull on him – in his novels and outside of them – to climb the ladder in

inverse, on the other side scaling it, maybe stamping on a few desperate

handholds as he went. For me, Imperial Bedrooms is the

apothesis of that tendency, or surrender to it, like an alcoholic’s messy

cave-in. Lunar Park‘s self-interrogations, its most

articulate presentation in his work yet of the opportunity money, fame, power,

provides for mediating personal pathologies through the self-cannibalism of

perfecting cultural chic – gave me hope he might have seen that plane in his

own career as the lever to a new event in his writing but, no.

Glamorama is such a good book, such a strong follow-up,

because it struggles with this the most subconsciously of all his books, and so

I read LP as a bringing of that into consciousness: Freud’s wo es war,

soll Ich werden [where Id was, there shall Ego be]. But instead that

id has become supergo in recent Ellis, seemingly “disenchanted” but

essentially cynical, luxury-padded fetish of misanthropy that is coterminous

with his desire to be heard as a celebrity and celeberatorily be heard. You see

early signs of it in his maudlin, self-fascinated tendency to bring back all of

his characters -whether just as a mentions – in a closed, soap-episodic loop.

That’s not a problem because of the genealogical, soapy connectivity – the sort

of genre-type saga aspect to it – but because it’s genuinely taken by Ellis as

a sign that he’s invented something as serious as a Dynasty with his

characters, to which I say blurk. See also, in that respect, his recent,

endlessly irritating, totally

pasted-together-from-innumerable-kinds-of-bullshit article on Charlie Sheen and

the mentality of “Post-Empire” for more of this tendency, for a loop

that has turned his wanting, involuted mediocrities (whether of characters or

culturally ‘relevant’, if controversial, opinions) into things he sees as truly

charismatic and at the centre of everything, a thing his writing at least –

perhaps not him – used to know they were not (hence that ever-escalating pathos

you so rightly detect, B). What’s more, just to close out

my argument on his recent Horatio Alger bit, the result has also been to make

Ellis become something like today’s version of Tom Wolfe (although I still hold

out some hope he might be able to claw himself back from the muckslide). Ever

since Ellis pressed the delete button on what was obviously his old, 90s-based

deeply intense public anxiety about his sexuality (also present

in Palahniuk: and such a truly embarassing problem to have dogging you today,

when being out is now a moral mandatory: the new closet, if you will), his new

nonfictional commentator persona has tried to present itself as a type of

wised-up, diva-ish cultural troll. And, indeed,

that persona is trolling – that’s Ellis’s Twitter feed in a nutshell – but not

subversively, especially not sexually subversively. Just the other day actually

I was saying to someone else about Ellis that he thinks his trolling is not

trolling (or that it is con-trolled) because he knows it’s trolling. But that

is just trolling: trolling includes that self-awareness in advance, that’s

exactly it’s energy-bleeding narcissism. His newest

cultivation of himself as a misanthrope, therefore, is anything but. You can’t

be in love with yourself as a human and evince the kind of ersatz disgust for

‘human nature’, spiced with a bad appropriation of catty conformist queerdom

(mostly by straight commentators), you see him use to attack mainstreamy camp

aesthetics via his supposedly “dangerous” anti-PC remarks about their

popularity and spread, remarks that make him try to come over as authentically

anarcho-gay or something rather than a “disher” trying to enhance

their own portfolio. (Think here of his squib on ‘Glee’ and the newest

round of ‘controversy’ that generated).

Before the recent turn down Fuckturd Boulevard, AP caused utterly authentic

upset – as did Glamorama, though more low key, in its

initial receipt of almost universally negative reviews claiming it ‘mediocre’

(it’s not). In the case of AP, I sense that it The assumption of it as

autobiography is what made AP a horror: it’s confessional,

a whistleblowing: “[Bateman] was crazy the same way [I

was]. He did not come out of me sitting down and wanting to write a grand

sweeping indictment of yuppie culture. It initiated because my own isolation

and alienation at a point in my life. I was living like Patrick Bateman.”

Too, people don’t get how densely allusive the novel is,

beyond commercially allusive, which seems to wall so much of it. For instance,

that segment you clip as example of being in Bateman’s, and your, and any,

head, the one that runs from “J&B I am thinking” to “Cellular

phone I am thinking”: it’s the psychoanalytic free associative method, the

interpretation of dreams, applied in an environment where the whole concept of

what free association would even mean comes up against the

liberated vanguard of circulation, of its endless, expensive, needable things.

Also, take the notorious rat scene: the pornographic focus on it as some

unparalleled moment of sickness in literature overlooks how long the historical

and literary pedigree to that moment is. Rat torture, of course, was one of the

most vicious tortures in the medieval arsenal, which is telling in itself, but

there’s also a much more important, recent echo: in Europe, the rat torture was

associated by fascist and liberal propaganda with the ‘Asiatic barbarism’ of

the totalitarian police of Soviet Russia (whether it did happen or not remains

questionable, which, given the Soviet predilection for punctiliously

documenting all its atrocities in secret archives, suggests that it likely did

not happen, but that’s neither here nor there, ultimately). For fascist

rhetoric, the rat torture was symbolic of a hugely powerful logic, in which totalitarian

crimes that far surpassed the rat torture could become freely permitted (that

is to say, we’re coterminous with civilization) in the name of self-protection

against the vile barbarism of Soviet totalitarianism. Think here, also, then, of

Orwell’s 1984 and how the final means of annihilating

Winston Smith’s resisting mind is via the prospect of the rat torture. The

point of all this is that Ellis, perhaps only intuitively, knowingly or not,

via the rat torture, and its sexual channel, implies that we are

living in totalitarian times and accredits the rat torture not to the

victim but to our resistance to the victim, to victimization carried out by the

cult of the sufferer (that is Bateman in a nutshell) itself. The book abounds

with densely layered referential moments like these that are astonishingly literate

and astonishingly intimate. And that’s not even to get into Dante: abandon

all hope, ye who enter here. Or the parallels to Alfred Hitchcock’s

Psycho.

And,

indirectly, in regards to that last reference: it’s also interesting, that in

Lunar Park Ellis decides to refine Bateman by letting it be

known this character is not only about himself but about his father, an earlier

generation. There’s a cult in America of the times before the Reagan Eighties,

the good times, when Democrats ruled and even Nixon was a Keynesian. What seems

to be totally demolished from the brain is that this was the moment in which

the State Department carried out direct prosecutions of dissidents, when

segregation ruled the land, when the FBI operated as a semi-autonomous,

extra-constitutional domestic police, when the National Guard shot protestors,

when the CIA executed a world-wide campaign of bloody coups that gave

us neoliberalism via the freedom to experiment with extreme

capitalism in ‘the colonies’, when the wealth of the working class funded anti-communist

wars in Korea and Vietnam that murdered millions, when worker self-organization

was repressed by a corporatist collusion between the state, business and nepotistic

union arrangements, who did untold good for a generation (not union-bashing

here) but via a compact with capital that depended on sustaining its power,

through wage bargaining, to bribe their base away from the most radical

redistributions of control (indeed, where does the entire fifties and sixties

postwar alienated horror of ‘the man in the grey flannel suit’ – the sadistic,

straightjacked menace of the ordinary, quivering with barely contained violence

– come from if not from this truncation of worker autonomy into the

professionalism of achievable rank?). In a sense, Lunar Park

excavates the generational continuity between the two times, not least through the

haunting of Ellis’s mansion. And what makes that such a fascinating ret-con is

precisely that it rehabilitates Bateman from the status of 80s slasher and

reasserts him as always having been the ghost in the machine

of our acquisitive psychogeographies: he is the reason we blank.

The blankness of the speech, the inability to be understood when we state it

plainly, the clippings of consciousness: the wall is the secret history of Bateman’s

unavowable existence as necessary to make all of this be. For which reason,

that ending to me is the most sublime mindfuck, insofar as Bateman’s vision is

a con, a sublimation of the ultimate

levelling as though desolation were peace. Notice how it is so carefully framed

by the sentimentalism of the elements and of the spirit, reason and light forms

it supposedly disavows of clarity, reality, vitalism: this is the ideological

endpoint that allows him to think only of an out in which we level everything

to zero: “…where there was nature and earth, life and water,

I saw a desert landscape that was unending, resembling some sort of crater,

so devoid of reason and light and spirit that the mind could not grasp it on

any sort of conscious level and if you came close the mind would reel backward,

unable to take it in. It was a vision so clear and real and vital

to me that in its purity it was almost abstract. This was what I could

understand, this was how I lived my life, what I constructed my movement

around, how I dealt with the tangible.” But, as the book’s interdiction on

apocalypticism at the end makes plain, “this is not an exit”.

Imperial

Bedrooms has actually dumped all that was brilliant about this – and about

Lunar Park’s reflection and reorientation of it, by actually

providing that exit: that endorsement of the crater as the truth, rather than

the most consummate perfection of the lie. I suppose Ellis think he’s taken it

to the next level in IB but that’s the difficult part of

being a genius: sometimes there’s no next level – either you move on to a

different thing or, doing the easy thing and retreading the wheel, you become a

hack. That’s where I stand on Ellis today. But I think Psycho

will always stands above that.

This makes me think of something you posted a couple of weeks (months?) ago, about what books we had read a second time lately. I just finished rereading AP, for a conference I’m working on about the literary NYC, and the sheer intelligence of it impressed me on a deep level. I coudn’t say that I agree with most of what you write here – for me, it really is a book about superficial and shallow human beings, Patrick being the epitome of this, he forfeited his humanity long ago – but this post is great nevertheless.

It seems to me, in a bizarre kind of way, that AP is the perfect exemple of the novel as TEXT, or DISCOURSE, a lexical environment where every single detail can be understood, can be felt, to be something and its opposite at the same time. Obviously, the mere existence of the murders themselves is the perfect illustration of this, because its impossible to decide if they’re real or not. Or that “Manhattan, Chase” scene, where there’s a narrative slip to the third person. Or the passage of time, which doesn’t make sense at all, it’s June, and then it’s August, and then it’s May again. The book is so brilliantly conceived, constructed, it is kind of mind blowing. I really think it’s everything but naive and even if Patrick is not “human”, we, as reader, tend to look for his humanity, dissecting him because he is incapable of doing so. That is the greatest trick of the novel, and of its narrator: to manipulate us into making a human being out of him.

Ellis goes even further with that kind of postmodernism and “undecidability” in Glamorama, but it’s less engaging because the scale is way bigger. I mean, there are models terrorists in there or something…

– sorry everybody if the English is not quite perfect, I’m French Canadian, be indulgent :) –

This – “When a book is read as if we, the reader, are

its receiver, instead of the book receiving us, that’s how the function of art

is slowly, over time, destroyed.” – is one of the most amazing sentences

I’ve read this year. This whole review was a model of what the form should be. Thanks

so much for this incredible review, Blake. I really like that you like it, that

it was able to turn your head on its neck. And that you get so much of what is

left out of its reception: I don’t know if I’ve read anything on

AP that synthesises so much of how I feel about its

much-deserved massiveness as this. Despite all the emphasis on its affectlessness,

I don’t get how people can not see that the book is so genuinely felt, a blood and sweat labour of love (imagine the

intensity of writing this thing: how can people say it has

no feeling?), and how that – not “disaffection” – is what makes it a truly milestone novel.

Before you get to it, you can’t help but think that, with

such a ‘high concept’ premise, there’s only so much it could possibly do:

serial killer on Wall Street premise, cute, clever, essentially overstated,

ready for its close-up and its movie deal. No. The book caused such

controversy, I’d say, before and on its release, because its concept is not

social satire at all: this book is realism, plain and true. Not formally, I

mean, but in content: it is totally a non-fiction as only fiction can do it. Also,

realism in that it takes itself 100% seriously. And it is funny because

of that: because it is so trapdoored with incongruities and juxtapositions

that are partake only of its utter hewing to the plane of its reality. Like most

comedy, though, it is also not funny at all for many people,

both today where it’s become this sober ‘moral novel’ of eighties excess, but

also especially back when it was first released, as was evidenced by the

baffled rage in the NY-oriented literary salon world, who analogue the

predations of Wall Street with their human cultural alibis that patina the

sadism of accumulative practice with the sentimental mawkishness of being a

human being, as well as the tabloid morality of media muckrakers. On that

point, it’s worth remembering that the hatred of this novel was largely a

confected controversy, a mix of government censorship bureaus,

risk-averse publishing circuits, astroturfed grassroots letter-writing hysteria

(death threats, etc.), literary ‘critics’ unhappy with the death of the book

this novel takes for granted to tell its most literary story, all dotted by the

occasional long-assimilated (and simultaneously indentured to be the chosen

targets of villification because it’s so damn easy) feminist talking head

against the book, like Gloria Steinem, who, mind you, were the only feminists

the media chose to spotlight, precisely because they were meant to represent moral

reaction, not feminism. (It’s no surprise to me that a woman ended up

eventually making the movie version, and brilliantly too.)

It severely disappoints me how acculturated Ellis has become today when he

talks about Psycho and its reception these days. Almost

invariably he makes some sneering anti-feminist remark (whether this is ‘how he

really feels’ or just controversy is a boring argument with Ellis-defenders and

besides the point, because it’s the very provocative narcissistic soundbiting

that is itself the biggest fail, with the recent casual misogyny only its

over-sugared frosting). You talk about hating how Wallace spoke of his own work

(me too: for starters, dude was far, far, far darker and against ideas of some

ultimate saving grace than he thought he was); that’s how I feel about Ellis,

especially now, after Imperial Bedrooms, which is a strong

contender for the worst book I feel I’ve read in the last five years. That

sounds like a big statement but I’ve thought long and hard about its fatuity as

a creation and it deserves the diss. (Though I’d be very interested to know

what you thought of it, of course.) Particularly, there’s always been an

undertow in Ellis of a half-baked “becoming who you are” idea on the

relation between celebrity and biography, the Horatio Alger Ellis, delineated

by a pull on him – in his novels and outside of them – to climb the ladder in

inverse, on the other side scaling it, maybe stamping on a few desperate

handholds as he went. For me, Imperial Bedrooms is the

apothesis of that tendency, or surrender to it, like an alcoholic’s messy

cave-in. Lunar Park‘s self-interrogations, its most

articulate presentation in his work yet of the opportunity money, fame, power,

provides for mediating personal pathologies through the self-cannibalism of

perfecting cultural chic – gave me hope he might have seen that plane in his

own career as the lever to a new event in his writing but, no.

Glamorama is such a good book, such a strong follow-up,

because it struggles with this the most subconsciously of all his books, and so

I read LP as a bringing of that into consciousness: Freud’s wo es war,

soll Ich werden [where Id was, there shall Ego be]. But instead that

id has become supergo in recent Ellis, seemingly “disenchanted” but

essentially cynical, luxury-padded fetish of misanthropy that is coterminous

with his desire to be heard as a celebrity and celeberatorily be heard. You see

early signs of it in his maudlin, self-fascinated tendency to bring back all of

his characters -whether just as a mentions – in a closed, soap-episodic loop.

That’s not a problem because of the genealogical, soapy connectivity – the sort

of genre-type saga aspect to it – but because it’s genuinely taken by Ellis as

a sign that he’s invented something as serious as a Dynasty with his characters, to which I say blurk. See also, in that respect, his recent,

endlessly irritating, totally

pasted-together-from-innumerable-kinds-of-bullshit article on Charlie Sheen and the mentality of “Post-Empire” for more of this tendency, for a loop

that has turned his wanting, involuted mediocrities (whether of characters or

culturally ‘relevant’, if controversial, opinions) into things he sees as truly

charismatic and at the centre of everything, a thing his writing at least –

perhaps not him – used to know they were not (hence that ever-escalating pathos

you so rightly detect, B). What’s more, just to close out

my argument on his recent Horatio Alger bit, the result has also been to make

Ellis become something like today’s version of Tom Wolfe (although I still hold

out some hope he might be able to claw himself back from the muckslide). Ever

since Ellis pressed the delete button on what was obviously his old, 90s-based

deeply intense public anxiety about his sexuality (also present

in Palahniuk: and such a truly embarassing problem to have dogging you today,

when being out is now a moral mandatory: the new closet, if you will), his new

nonfictional commentator persona has tried to present itself as a type of

wised-up, diva-ish cultural troll. And, indeed,

that persona is trolling – that’s Ellis’s Twitter feed in a nutshell – but not

subversively, especially not sexually subversively. Just the other day actually

I was saying to someone else about Ellis that he thinks his trolling is not

trolling (or that it is con-trolled) because he knows it’s trolling. But that

is just trolling: trolling includes that self-awareness in advance, that’s

exactly it’s energy bleeding narcissism. His newest

cultivation of himself as a misanthrope, therefore, is anything but. You can’t

be in love with yourself as a human and evince the kind of ersatz disgust for

‘human nature’, spiced with a bad appropriation of catty conformist queerdom (mostly by straight commentators), you see him use to attack mainstreamy camp aesthetics via his supposedly “dangerous” anti-PC remarks about their

popularity and spread, remarks that make him try to come over as authentically

anarcho-gay or something rather than a “disher” trying to enhance

their own portfolio. (Think here of his squib on ‘Glee’ and the newest

round of ‘controversy’ that generated).

Before the recent turn down Fucktard Boulevard, AP caused utterly authentic

upset – as did Glamorama, though more low key, in its

initial receipt of almost universally negative reviews claiming it ‘mediocre’

(it’s not). In the case of AP, I sense that it The assumption of it as

autobiography is what made AP a horror: it’s confessional, a whistleblowing: “[Bateman] was crazy the same way [I

was]. He did not come out of me sitting down and wanting to write a grand

sweeping indictment of yuppie culture. It initiated because my own isolation

and alienation at a point in my life. I was living like Patrick Bateman.”

Too, people don’t get how densely allusive the novel is,

beyond commercially allusive, which seems to wall so much of it. For instance,

that segment you clip as example of being in Bateman’s, and your, and any,

head, the one that runs from “J&B I am thinking” to “Cellular

phone I am thinking”: it’s the psychoanalytic free associative method, the

interpretation of dreams, applied in an environment where the whole concept of

what free association would even mean comes up against the liberated vanguard of circulation, of its endless, expensive, needable things.

Also, take the notorious rat scene: the pornographic focus on it as some

unparalleled moment of sickness in literature overlooks how long the historical

and literary pedigree to that moment is. Rat torture, of course, was one of the

most vicious tortures in the medieval arsenal, which is telling in itself, but

there’s also a much more important, recent echo: in Europe, the rat torture was

associated by fascist and liberal propaganda with the ‘Asiatic barbarism’ of

the totalitarian police of Soviet Russia (whether it did happen or not remains questionable, which, given the Soviet predilection for punctiliously

documenting all its atrocities in secret archives, suggests that it likely did

not happen, but that’s neither here nor there, ultimately). For fascist

rhetoric, the rat torture was symbolic of a hugely powerful logic, in which totalitarian

crimes that far surpassed the rat torture could become freely permitted (that

is to say, we’re coterminous with civilization) in the name of self-protection

against the vile barbarism of Soviet totalitarianism. Think here, also, then, of

Orwell’s 1984 and how the final means of annihilating

Winston Smith’s resisting mind is via the prospect of the rat torture. The

point of all this is that Ellis, perhaps only intuitively, knowingly or not,

via the rat torture, and its sexual channel, implies that we are

living in totalitarian times and accredits the rat torture not to the

victim but to our resistance to the victim, to victimization carried out by the

cult of the sufferer (that is Bateman in a nutshell) itself. The book abounds

with densely layered referential moments like these that are astonishingly literate

and astonishingly intimate. And that’s not even to get into Dante: abandon

all hope, ye who enter here. Or the parallels to Alfred Hitchcock’s

Psycho.

And, indirectly, in regards to that last reference: it’s also

interesting, that in Lunar Park, his most Hitchcockian novel, Ellis decides to refine Bateman

by letting it be known this character is not only about himself but about his

father, an earlier generation. There’s a cult in America of the times before

the Reagan Eighties, the good times, when Democrats ruled and even Nixon was a

Keynesian. What seems to be totally demolished from the brain is that this was

the moment in which the State Department carried out direct prosecutions of

dissidents, when segregation ruled the land, when the FBI operated as a

semi-autonomous, extra-constitutional domestic police, when the National Guard shot protestors, when the CIA executed a world-wide campaign of bloody coups

that gave us neoliberalism via the freedom to experiment

with extreme capitalism in ‘the colonies’, when the wealth of the working class

funded anti-communist wars in Korea and Vietnam that murdered millions, when worker

self-organization was repressed by a corporatist collusion between the state,

business and nepotistic union arrangements, who did untold good for a

generation (not union-bashing here) but via a compact with capital that

depended on sustaining its power, through wage bargaining, to bribe their base away from the most radical redistributions of control (indeed, where does the entire

fifties and sixties postwar alienated horror of ‘the man in the grey flannel

suit’ – the sadistic, straightjacked menace of the ordinary, quivering with

barely contained violence – come from if not from this truncation of worker

autonomy into the professionalism of achievable rank?). In a sense,

Lunar Park excavates the generational continuity between the two times, not least through the haunting of Ellis’s mansion. And what makes

that such a fascinating ret-con is precisely that it rehabilitates Bateman from

the status of 80s slasher and reasserts him as always having been the

ghost in the machine of our acquisitive psychogeographies: he

is the reason we blank. The blankness of the speech, the inability to

be understood when we state it plainly, the clippings of consciousness: the

wall is the secret history of Bateman’s unavowable existence as necessary to

make all of this be. For which reason, that ending to me is the most sublime mindfuck, insofar as Bateman’s vision is a con, a sublimation of the ultimate levelling as though desolation

were peace. Notice how it is so carefully framed by the sentimentalism of the

elements and of the spirit, reason and light forms it supposedly disavows of clarity, reality, vitalism: this is the ideological endpoint that allows him to think

only of an out in which we level everything to zero: “…where there was nature

and earth, life and water, I saw a desert landscape that was

unending, resembling some sort of crater, so devoid of

reason and light and spirit that the mind could not grasp it on any sort of

conscious level and if you came close the mind would reel backward, unable to take it in. It was a vision so clear and real and vital to

me that in its purity it was almost abstract. This was what I could understand,

this was how I lived my life, what I constructed my movement around, how I

dealt with the tangible.” But, as the book’s interdiction on apocalypticism at

the end makes plain, “this is not an exit”.

Imperial Bedrooms has actually dumped all

that was brilliant about this – and about Lunar Park’s

reflection and reorientation of it, by actually providing that exit: that

endorsement of the crater as the truth, rather than the most consummate

perfection of the lie. I suppose Ellis think he’s taken it to the next level in

IB but that’s the difficult part of being a genius:

sometimes there’s no next level – either you move on to a different thing or, doing

the easy thing and retreading the wheel, you become a hack. That’s where I

stand on Ellis today. But I think Psycho will always stands

above that.

╔═══╗ ♪║███║ ♫║ (●) ♫╚═══╝♪♪╔═══╗ ♪║███║ ♫║ (●) ♫╚═══╝♪♪╔═══╗ ♪║███║ ♫║ (●) ♫╚═══╝♪♪

This – “When a book is read as if we, the reader, are

its receiver, instead of the book receiving us, that’s how the function of art

is slowly, over time, destroyed.” – is one of the most amazing sentences

I’ve read this year. This whole review was a model of what the form should be. Thanks

so much for this incredible review, Blake. I really like that you like it, that

it was able to turn your head on its neck. And that you get so much of what is

left out of its reception: I don’t know if I’ve read anything on

AP that synthesises so much of how I feel about its

much-deserved massiveness as this. Despite all the emphasis on its affectlessness,

I don’t get how people can not see that the book is so genuinely

felt, a blood and sweat labour of love (imagine the

intensity of writing this thing: how can people say it has

no feeling?), and how that – not “disaffection” – is what makes it a truly milestone novel.

Before you get to it, you can’t help but think that, with

such a ‘high concept’ premise, there’s only so much it could possibly do:

serial killer on Wall Street premise, cute, clever, essentially overstated,

ready for its close-up and its movie deal. No. The book caused such

controversy, I’d say, before and on its release, because its concept is not

social satire at all: this book is realism, plain and true. Not formally, I

mean, but in content: it is totally a non-fiction as only fiction can do it. Also,

realism in that it takes itself 100% seriously. And it is funny because

of that: because it is so trapdoored with incongruities and juxtapositions

that are partake only of its utter hewing to the plane of its reality. Like most

comedy, though, it is also not funny at all for many people,

both today where it’s become this sober ‘moral novel’ of eighties excess, but

also especially back when it was first released, as was evidenced by the

baffled rage in the NY-oriented literary salon world, who analogue the

predations of Wall Street with their human cultural alibis that patina the

sadism of accumulative practice with the sentimental mawkishness of being a

human being, as well as the tabloid morality of media muckrakers. On that

point, it’s worth remembering that the hatred of this novel was largely a

confected controversy, a mix of government censorship bureaus,

risk-averse publishing circuits, astroturfed grassroots letter-writing hysteria

(death threats, etc.), literary ‘critics’ unhappy with the death of the book

this novel takes for granted to tell its most literary story, all dotted by the

occasional long-assimilated (and simultaneously indentured to be the chosen

targets of villification because it’s so damn easy) feminist talking head

against the book, like Gloria Steinem, who, mind you, were the only feminists

the media chose to spotlight, precisely because they were meant to represent moral

reaction, not feminism. (It’s no surprise to me that a woman ended up

eventually making the movie version, and brilliantly too.)

It severely disappoints me how acculturated Ellis has become today when he

talks about Psycho and its reception these days. Almost

invariably he makes some sneering anti-feminist remark (whether this is ‘how he

really feels’ or just controversy is a boring argument with Ellis-defenders and

besides the point, because it’s the very provocative narcissistic soundbiting

that is itself the biggest fail, with the recent casual misogyny only its

over-sugared frosting). You talk about hating how Wallace spoke of his own work

(me too: for starters, dude was far, far, far darker and against ideas of some

ultimate saving grace than he thought he was); that’s how I feel about Ellis,

especially now, after Imperial Bedrooms, which is a strong

contender for the worst book I feel I’ve read in the last five years. That

sounds like a big statement but I’ve thought long and hard about its fatuity as

a creation and it deserves the diss. (Though I’d be very interested to know

what you thought of it, of course.) Particularly, there’s always been an

undertow in Ellis of a half-baked “becoming who you are” idea on the

relation between celebrity and biography, the Horatio Alger Ellis, delineated

by a pull on him – in his novels and outside of them – to climb the ladder in

inverse, on the other side scaling it, maybe stamping on a few desperate

handholds as he went. For me, Imperial Bedrooms is the

apothesis of that tendency, or surrender to it, like an alcoholic’s messy

cave-in. Lunar Park‘s self-interrogations, its most

articulate presentation in his work yet of the opportunity money, fame, power,

provides for mediating personal pathologies through the self-cannibalism of

perfecting cultural chic – gave me hope he might have seen that plane in his

own career as the lever to a new event in his writing but, no.

Glamorama is such a good book, such a strong follow-up,

because it struggles with this the most subconsciously of all his books, and so

I read LP as a bringing of that into consciousness: Freud’s wo es war,

soll Ich werden [where Id was, there shall Ego be]. But instead that

id has become supergo in recent Ellis, seemingly “disenchanted” but

essentially cynical, luxury-padded fetish of misanthropy that is coterminous

with his desire to be heard as a celebrity and celeberatorily be heard. You see

early signs of it in his maudlin, self-fascinated tendency to bring back all of

his characters -whether just as a mentions – in a closed, soap-episodic loop.

That’s not a problem because of the genealogical, soapy connectivity – the sort

of genre-type saga aspect to it – but because it’s genuinely taken by Ellis as

a sign that he’s invented something as serious as a Dynasty with his

characters, to which I say blurk. See also, in that respect, his recent,

endlessly irritating, totally

pasted-together-from-innumerable-kinds-of-bullshit article on Charlie Sheen and

the mentality of “Post-Empire” for more of this tendency, for a loop

that has turned his wanting, involuted mediocrities (whether of characters or

culturally ‘relevant’, if controversial, opinions) into things he sees as truly

charismatic and at the centre of everything, a thing his writing at least –

perhaps not him – used to know they were not (hence that ever-escalating pathos

you so rightly detect, B). What’s more, just to close out

my argument on his recent Horatio Alger bit, the result has also been to make

Ellis become something like today’s version of Tom Wolfe (although I still hold

out some hope he might be able to claw himself back from the muckslide). Ever

since Ellis pressed the delete button on what was obviously his old, 90s-based

deeply intense public anxiety about his sexuality (also present

in Palahniuk: and such a truly embarassing problem to have dogging you today,

when being out is now a moral mandatory: the new closet, if you will), his new

nonfictional commentator persona has tried to present itself as a type of

wised-up, diva-ish cultural troll. And, indeed,

that persona is trolling – that’s Ellis’s Twitter feed in a nutshell – but not

subversively, especially not sexually subversively. Just the other day actually

I was saying to someone else about Ellis that he thinks his trolling is not

trolling (or that it is con-trolled) because he knows it’s trolling. But that

is just trolling: trolling includes that self-awareness in advance, that’s

exactly it’s energy-bleeding narcissism. His newest

cultivation of himself as a misanthrope, therefore, is anything but. You can’t

be in love with yourself as a human and evince the kind of ersatz disgust for

‘human nature’, spiced with a bad appropriation of catty conformist queerdom

(mostly by straight commentators), you see him use to attack mainstreamy camp

aesthetics via his supposedly “dangerous” anti-PC remarks about their

popularity and spread, remarks that make him try to come over as authentically

anarcho-gay or something rather than a “disher” trying to enhance

their own portfolio. (Think here of his squib on ‘Glee’ and the newest

round of ‘controversy’ that generated).

Before the recent turn down Fuckturd Boulevard, AP caused utterly authentic

upset – as did Glamorama, though more low key, in its

initial receipt of almost universally negative reviews claiming it ‘mediocre’

(it’s not). In the case of AP, I sense that it The assumption of it as

autobiography is what made AP a horror: it’s confessional,

a whistleblowing: “[Bateman] was crazy the same way [I

was]. He did not come out of me sitting down and wanting to write a grand

sweeping indictment of yuppie culture. It initiated because my own isolation

and alienation at a point in my life. I was living like Patrick Bateman.”

Too, people don’t get how densely allusive the novel is,

beyond commercially allusive, which seems to wall so much of it. For instance,

that segment you clip as example of being in Bateman’s, and your, and any,

head, the one that runs from “J&B I am thinking” to “Cellular

phone I am thinking”: it’s the psychoanalytic free associative method, the

interpretation of dreams, applied in an environment where the whole concept of

what free association would even mean comes up against the

liberated vanguard of circulation, of its endless, expensive, needable things.

Also, take the notorious rat scene: the pornographic focus on it as some

unparalleled moment of sickness in literature overlooks how long the historical

and literary pedigree to that moment is. Rat torture, of course, was one of the

most vicious tortures in the medieval arsenal, which is telling in itself, but

there’s also a much more important, recent echo: in Europe, the rat torture was

associated by fascist and liberal propaganda with the ‘Asiatic barbarism’ of

the totalitarian police of Soviet Russia (whether it did happen or not remains

questionable, which, given the Soviet predilection for punctiliously

documenting all its atrocities in secret archives, suggests that it likely did

not happen, but that’s neither here nor there, ultimately). For fascist

rhetoric, the rat torture was symbolic of a hugely powerful logic, in which totalitarian

crimes that far surpassed the rat torture could become freely permitted (that

is to say, we’re coterminous with civilization) in the name of self-protection

against the vile barbarism of Soviet totalitarianism. Think here, also, then, of

Orwell’s 1984 and how the final means of annihilating

Winston Smith’s resisting mind is via the prospect of the rat torture. The

point of all this is that Ellis, perhaps only intuitively, knowingly or not,

via the rat torture, and its sexual channel, implies that we are

living in totalitarian times and accredits the rat torture not to the

victim but to our resistance to the victim, to victimization carried out by the

cult of the sufferer (that is Bateman in a nutshell) itself. The book abounds

with densely layered referential moments like these that are astonishingly literate

and astonishingly intimate. And that’s not even to get into Dante: abandon

all hope, ye who enter here. Or the parallels to Alfred Hitchcock’s

Psycho.

And, indirectly, in regards to that last reference: it’s also

interesting, that in Lunar Park Ellis decides to refine Bateman

by letting it be known this character is not only about himself but about his

father, an earlier generation. There’s a cult in America of the times before

the Reagan Eighties, the good times, when Democrats ruled and even Nixon was a

Keynesian. What seems to be totally demolished from the brain is that this was

the moment in which the State Department carried out direct prosecutions of

dissidents, when segregation ruled the land, when the FBI operated as a

semi-autonomous, extra-constitutional domestic police, when the National Guard

shot protestors, when the CIA executed a world-wide campaign of bloody coups

that gave us neoliberalism via the freedom to experiment

with extreme capitalism in ‘the colonies’, when the wealth of the working class

funded anti-communist wars in Korea and Vietnam that murdered millions, when worker

self-organization was repressed by a corporatist collusion between the state,

business and nepotistic union arrangements, who did untold good for a

generation (not union-bashing here) but via a compact with capital that

depended on sustaining its power, through wage bargaining, to bribe their base away

from the most radical redistributions of control (indeed, where does the entire

fifties and sixties postwar alienated horror of ‘the man in the grey flannel

suit’ – the sadistic, straightjacked menace of the ordinary, quivering with

barely contained violence – come from if not from this truncation of worker

autonomy into the professionalism of achievable rank?). In a sense,

Lunar Park excavates the generational continuity between the

two times, not least through the haunting of Ellis’s mansion. And what makes

that such a fascinating ret-con is precisely that it rehabilitates Bateman from

the status of 80s slasher and reasserts him as always having been the

ghost in the machine of our acquisitive psychogeographies: he

is the reason we blank. The blankness of the speech, the inability to

be understood when we state it plainly, the clippings of consciousness: the

wall is the secret history of Bateman’s unavowable existence as necessary to

make all of this be. For which reason, that ending to me is the most sublime

mindfuck, insofar as Bateman’s vision is a con, a sublimation of the ultimate levelling as though desolation

were peace. Notice how it is so carefully framed by the sentimentalism of the

elements and of the spirit, reason and light forms it supposedly disavows of clarity,

reality, vitalism: this is the ideological endpoint that allows him to think

only of an out in which we level everything to zero: “…where there was nature

and earth, life and water, I saw a desert landscape that was

unending, resembling some sort of crater, so devoid of

reason and light and spirit that the mind could not grasp it on any sort of

conscious level and if you came close the mind would reel backward, unable to

take it in. It was a vision so clear and real and vital to

me that in its purity it was almost abstract. This was what I could understand,

this was how I lived my life, what I constructed my movement around, how I

dealt with the tangible.” But, as the book’s interdiction on apocalypticism at

the end makes plain, “this is not an exit”.

Imperial Bedrooms has actually dumped all

that was brilliant about this – and about Lunar Park’s

reflection and reorientation of it, by actually providing that exit: that

endorsement of the crater as the truth, rather than the most consummate

perfection of the lie. I suppose Ellis think he’s taken it to the next level in

IB but that’s the difficult part of being a genius:

sometimes there’s no next level – either you move on to a different thing or, doing

the easy thing and retreading the wheel, you become a hack. That’s where I

stand on Ellis today. But I think Psycho will always stands

above that.

Sorry for the multiple comments and the weird formatting: signing up to disqus seems to have caused a headfuck. Could a mod delete the repeats, thanks?

“by leaving that sheen up, by complicating the

borderline redemptive qualities of Bateman, and feeding his only out

into a pathos that is terrifying in its operation in hurting other

humans, is actually even more human, more honest”

great insight, thanks for articulating this, blake

Interesting you mention that book, because I taught OUTER DARK alongside AP last spring . . .

disqus needs a love button

I wouldn’t even mind his homophobia if he’d just STFU about Empire/Post-empire

Man, this is the shit. In lack of a better term. HTML should be on a lock-out to let tardy readers access thee in, say, the following 2 weeks.

I’d quote point #8 in full, but where?

Emphasis on “just.”

what i’ve learned is to love dfw but to totally doubt his opinion on literature and that’s okay. rlly want to read american psycho now that i’ve realized my reasons (and yrs) for not wanting to are/were horseshit. sweet post.

When I feel that a book has been metabolized straight out of the mind and blood with craft that is evidence of force that clarifies complexity or boundary, I am or feel “better off”.

this was great. i havent read the book in a long while and this made me want to re-visit it. when friends want to read Ellis, i point them to American Psycho.

someone above mentioned that they won’t read anything else by Ellis, but Glamorama is brilliant. it is a similar ‘[shitting] straight out of the mind,’ a similar use of comedy of manners and random internal monologue, but much funnier, ironic and more heart-rending. plus, it’s essentially the same plot as Zoolander.

“I decide on the pilot fish with tulips and cinnamon…” Come on, American Psycho is really funny.

Well done. I’ve never read any of his work. Suggestions on the best for someone’s first?

i’ve been meaning to read this for so long. i’m not ashamed to admit Less Than Zero is one of my fav books. going to read American Psycho before summer’s end!

and you know this, how? personal experience?

also, aren’t we ALL complete assholes? i know i am.