Auguste D.

Imagine, Iphi said, how that scene doesn’t happen once. How it is happening right now, but also a thousand years ago and next week and next year and forty billion years after that.

Forever.

Forever and ever without end.

—Calendar of Regrets, January

*

In November 1901, at the mental hospital where he worked, Dr. Alois Alzheimer met a patient on his rounds named Auguste D., though she seldom remembered her name as such. Auguste D. was 51 years old, and she would become the first patient diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. In his interviews with Auguste D., Alzheimer uncovered a displaced psyche:

Auguste D.: “I have, so to speak, lost myself.”

:

Alzheimer: “Where are you?”

Auguste D.: “Here and everywhere—here and now—you mustn’t take offense.”

[Alzheimer: The Life of a Physician & The Career of a Disease, Maurer and Maurer]

Here is a woman who doesn’t know who she is in relation to the world, someone who has simultaneously lost herself and found herself everywhere, has become both corporeal rust and particulate dust.

We [read: society, read: artists] regard Auguste D.’s mental state with relative terror. She’s relegated to the realm of old, crazy people sequestered to wards that smell like vomit and bleach, folks who no longer matter. She’s the poster child for the hospitalized and sanitized. A symbol of deterioration and loss.

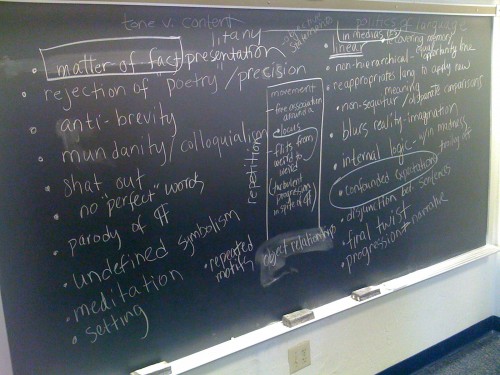

In his new book, Calendar of Regrets, Lance Olsen is speaking the language of forgetting. He seems to ask, just what about any life—or any death—is different from Auguste D.’s sense-displacement? Don’t let me confuse you. Calendar of Regrets is not about Alzheimer’s disease, though Auguste D. would have been the perfect addition to Olsen’s wild cast of characters.

In his new book, Calendar of Regrets, Lance Olsen is speaking the language of forgetting. He seems to ask, just what about any life—or any death—is different from Auguste D.’s sense-displacement? Don’t let me confuse you. Calendar of Regrets is not about Alzheimer’s disease, though Auguste D. would have been the perfect addition to Olsen’s wild cast of characters.

Calendar of Regrets is flanked by the mind-meanderings of the painter Hieronymus Bosch in the hours after he’s been (ostensibly) poisoned and leaks into the 1986 attack on Dan Rather in which his assailant asked, “Kenneth, What’s the Frequency?” This book steps inside the heads of mythological figures, radical Christian terrorists, a pirate radio station host broadcasting from the Salton Sea, a vacationing family hijacked by a pretty girl with a bomb in her bag, a backpacker in southeast Asia, a teacher who has lost herself amidst the chatter of teenagers, a time-space traveler, a man born as a notebook, a body made up of borrowed organs, a fallen angel whose presence folds time into a loop for two little boys.

In the big-picture narrative, Olsen’s characters have been temporarily—temporally—displaced, all lost, “here and everywhere—here and now,” and they’re connected chapter to chapter (and month to month on a 12-month calendar) by thought-events across space and time. One chapter ends and the next story picks up its sentence fragment to begin anew, and then the stories fold back on themselves until we end up back where we started. Sometimes the connections between stories are tenuous, but I’m willing to follow because, after all, isn’t that how memory works?

READ MORE >

In his new book, Calendar of Regrets, Lance Olsen is speaking the language of forgetting. He seems to ask, just what about any life—or any death—is different from Auguste D.’s sense-displacement? Don’t let me confuse you. Calendar of Regrets is not about Alzheimer’s disease, though Auguste D. would have been the perfect addition to Olsen’s wild cast of characters.

In his new book, Calendar of Regrets, Lance Olsen is speaking the language of forgetting. He seems to ask, just what about any life—or any death—is different from Auguste D.’s sense-displacement? Don’t let me confuse you. Calendar of Regrets is not about Alzheimer’s disease, though Auguste D. would have been the perfect addition to Olsen’s wild cast of characters.