TRUMP AND IMAGINARY SWEDES

1.

A couple of days ago, President Trump made headlines around the world when he suggested that there had been a terrorist attack in Sweden “last night.” This was a big surprise to many people, not the least people living in Sweden, since none of them had heard of an attack. As most of you now know, it was soon established that there had not been a terrorist attack, and that the US president had lied.

Many Swedish and international newspapers joined in to debunk Trump’s claim, and the Swedish government asked the US government for an official explanation. The only answer Trump seemed capable of offering was that he had been inspired by a recent story on “Tucker Carlson’s” show on Fox News. The show had interviewed a propagandist film-maker, Ami Horowitz, was in turn proven to have not only peddled falsehoods but to have cut-and-pasted interviews with Swedish police officers in such a way that it seemed that they were talking about immigrants when they in fact were not.

In response to continued pressure, Trump has insisted that things are really terrible in Sweden and that the news is trying to cover up the real truth about how horrible Sweden is.

It’s true that Sweden has let in a lot of immigrants over the past three decades. And it’s true that it’s often been hard for a country that previously had very few immigrants to deal with this influx, and that right-wing politicians have successfully riled up a lot of xenophobia. But the claims that Sweden has become crime-riddled war zone are incredibly, incredibly exaggerated. Stockholm is not “the rape capital of Europe” no matter how fanciful that claim strikes right-wingers. The increase of refugees has not led to a substantial increase in crime. There’s zero evidence to back up these claims.

Still, Trump won’t go back on his charges. Instead he’s doubled down, claiming to know Sweden better than Swedish scholars and journalists. Why? READ MORE >

“the limitless violence of beauty”: On Raúl Zurita

In the comment to my last post, “Deadgod” raised some good issues about “canons” and canonical thinking. When I disparage canonical thinking, I am disparaging the kind of stable lists and established readings that aims to contain poetry’s volatility. But I’m not opposed to people having favorite poets, or even of people promoting certain poets as great.

In his blurb to Anna Deeny Morales’s new selection of Raúl Zurita’s work, Sky Below: Selected Works, Forrest Gander writes: “There isn’t a more important contemporary writer than Raúl Zurita.”

I think this statement could be more than a blurb, I think it can model a very insightful mental exercise: Instead of assuming that a US poet – Ashbery, Bishop etc – is “the most important post-war poet” (as tends to be the assumption in US discussions about poetry), imagine an alternative reality (not all that alternative, if you happen to live not in the US but in Chile or any other part of the Spanish-speaking world) that Raúl Zurita is the most important contemporary poet.

How would that change all kinds of assumptions about poetry?

For example, in Zurita’s work lyrical poetry and politics are not opposed, as in so much US thinking about poetry. The lyrical is political; the lyric also has the capacity to embrace the public, the visionary, dreams, the abject; the lyrical can be excessive and overwhelming, not a call to be moderate/”incremental” and “write what you know”; the avant-garde is not to be obscure or elite, but to be dramatically populist (as it was for example for the Dadaist poster-makers in Germany, 1930s). I think especially in times such as this, Zurita’s fierce work – embracing performance work as well as lyrics – is a great source of inspiration for me.

From an interview with Prairie Schooner:

“All that I came to do in those years, like the art actions with the CADA, was because I felt that pain and death should be responded to with a poetry and an art that was as vast and strong as the violence that was exercised over us. To place in opposition the limitless violence of crime and the limitless violence of beauty, the extreme violence of power and the extreme violence of art, the violence of terror and the even stronger violence of all our poems. I never knew how to throw stones, but that was not our intifada. You can’t defeat a dictatorship with poetry, but without poetry, and this is no metaphor, humanity disappears, literally, in the next five minutes.”

However, I think calling attention to the greatness of Zurita is only good if we do away with the common treatment whereby foreign writers are “allowed” to write about political calamity but that conditions are different for US poets (as in many discussions about “the poetry of witness” etc). Or that Zurita stands for a kind of separate, quarantined, foreign canonicity. That’s stabilizing canonicity.

No, I think we should insist – with Gander – that Zurita is someone for US poets to take to heart as much as they take to heart US poets, or even more than they take to heart US poets. This is one of the threats and promises of translation’s “transgressive circulation”: that a foreign poet can be “canonical” and utterly challenge our assumptions about poetry.

In an increasingly untenable situation in this country, I am inspired by Zurita’s call for a poetry that is “as vast and strong” as the forces of injustice, a call for an “extreme” poetry that invokes and engages with “the limitless violence of beauty.”

Volatile Translations: On Paul Cunningham and Sara Tuss Efrik’s Manias

1.

In my last post about translation and Ali Taheri Araghi’s anthology of contemporary, underground poetry from Iran, I pointed out that a big reason for the anxiety about translation comes form our literary establishment’s anxiety about excess: Translation produces too many versions of too many texts, from too many lineages and too many languages.

Just as the reaction against the threat of the plague ground is to constantly make canons and lists of the truly good, truly “legit” poetry (prestige is the opium of the poets), I see the same thing going on in translation: we make hierarchies. We want there to be a foreign canon which will be as stable as the US canon – though there’s always a struggle to erect and maintain these canons since different people have different aesthetics and views.

Beneath this model and its anxieties we can sense what scholar-poet Susan Stewart has, in her wonderful book “On Longing” described like this: “… in the contextualist’s privileging of context of situation we see a Romanticism directed toward a lost point of origin, a point where being-in-context supposedly allowed for a complete and totalized understanding.” There is no origin where we can have “totalized understanding,” no matter how much such writers wish to demonstrate mastery. In the plague ground of poetry, poets and translations infect each other, deform each other. We lose the sense of the true original, the gold standard of interpretation, the master taste. READ MORE >

Transgressive Circulation: Alireza Taheri Araghi and “Younger Iranian Poets”

1.

In my last post, I wrote that I see a lot of anxiety about translations in US literary discussions: “… the threat of translation is the threat of a kind of excess: too many versions of too many texts by too many authors from too many lineages.” Once you add the writing form another country, the illusion of objectivity of a single “tradition” is put in doubt (of course this dynamic is often at play in smaller, non-major countries).

One way this anxiety is manifested is in the skepticism about foreign texts. Whenever there’s a translation, people wonder: Is this really a major writer? Does this writer really deserve to be translated into our language? Is this translation really correct or is it corrupting the truly great poet? Or, as I noted in the essay I linked to last post, are the “young American poets” being “improperly influenced” by foreign writers without having mastered their tradition.

2.

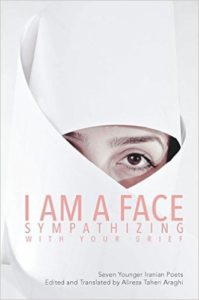

In his anthology “I Am A Face Sympathizing With Your Grief,” Alireza Taheri Araghi shows no intention of creating an illusory alternative canon of great works of Iran. Instead he has searched out underground poets – or more correctly, Internet poets – who have not been deemed publishable by the Iranian government. In a sense Araghi has done the opposite of the typical canonical anthology; he has chosen “young” poets who excite him, many who have little or none of the official recognition that translation discourse tends to demand.

Transgressive Circulation: Translation, foreign threats, and counterfeit teenagers

Hi, I thought I would write a few posts about recent translation titles. But before I do that, I thought I would post a link to an essay I wrote about translation which was just published in the Australian journal, Cordite Review. Hopefully it provides some kind of framework for the kinds of issues I will talk about in future posts.

Here’s an excerpt:

1.

At the AWP writers’ conference in Minneapolis a couple of years ago, I attended a panel on Paul Celan’s poetry. In the Q & A that followed the panel, the first question was ‘How can we make sure that young American poets are not improperly influenced by Celan’s poetry without truly understanding it?’ The panel responded by offering a variety of possible solutions, such as reading the extensive literature about the poet or reading his letters and journal entries that have been published as well. However, none of them asked why it should be that this ‘improper influence’ should be the audience member’s biggest concern. I begin with this anecdote because it immediately struck me that the seemingly innocent question went to the heart of the marginalisation of translation in U.S. literature. In U.S. literary discussions, translations are – time after time – marginalised or dismissed in rhetoric that portrays translations as false, improper, counterfeit or of shallow ‘influence.’ The foreign poet is seen as a threat because he or she will ‘influence’ the young American poets who are vulnerable to such foreign forces, incapable of seeing the foreign writer in the proper ‘context’ (that is to say, one that is different from their own). These discussions about the dangers of the ‘foreign influence’ of translated texts betrays a fundamental anxiety about the ‘transgressive circulation’ of texts: an anxiety about the way they move from one context to another, about the way foreign entities may trouble our sense of agency and interiority.1

2.

In the question at the panel, the danger of foreign influence was posited as the dangers of foreign texts seducing the young. The question comes out of a worldview in which the ignorant enthusiasm of the ‘young American poets’ for the foreign texts threaten to make a hoax out of the foreign – make a counterfeit Celan. In their permeability, these hypothetical ‘young American poets’ become purveyors of kitsch, reverse alchemists who turn gold into trash by bringing the foreign into U.S. literature without the proper knowledge or mastery of the foreign. These young American poets insist on a close contact with the foreign, where such communication should be impossible. They are readers who may confuse the boundaries – between U.S. and foreign poetry, between greatness and counterfeitness. They have not yet learned the important distinctions of what belongs and what doesn’t – and most importantly, how to read poetry correctly. Their shallowness – their lack of learning – may cause them to imitate a bad model, or imitate good models for the wrong reasons (I imagine that the questioner at the Celan panel was concerned about Celan’s use of neologisms, for example.). In the terms of Mary Douglas’s argument about ‘pollution symbolism’ – later used by Julia Kristeva in her formation of the idea of abjection – the young poets are the sites of possible contamination, sites where the U.S. literary landscape becomes vulnerable to foreign influence. The question may at first have appeared to be about the learning of Celan, but ultimately it’s a question about keeping the foreign away from U.S. poetry, or keeping it at a safe distance.