“Furthermore, the amateur poets were more likely to use more emotional words, both negative and positive.”

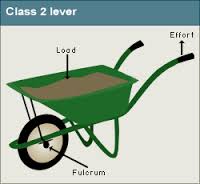

Y’all relax OK Australia finally figured out contemporary American poetry y’all. Post your scores, losers. > 0.5 is professional and < 0.5 is amateur. Be sure to read the, um, “methodology.” According to poetry journalist Patrick Gaughan, the highest so far (at 4.2) is WCW’s good old wheelbarrow coloring book, and noted anti-poetry skeptic/fiction engineer Jonathan Volk reports that “an untitled Jewel poem just got a 1.17.” Stay tuned for breaking developments. (Discovery credit goes to poetry scientist Anne Cecelia Holmes.)

Y’all relax OK Australia finally figured out contemporary American poetry y’all. Post your scores, losers. > 0.5 is professional and < 0.5 is amateur. Be sure to read the, um, “methodology.” According to poetry journalist Patrick Gaughan, the highest so far (at 4.2) is WCW’s good old wheelbarrow coloring book, and noted anti-poetry skeptic/fiction engineer Jonathan Volk reports that “an untitled Jewel poem just got a 1.17.” Stay tuned for breaking developments. (Discovery credit goes to poetry scientist Anne Cecelia Holmes.)

A bit more on Susan Sontag and “Against Interpretation”

I’m still bogged down with school (almost done) but I thought I’d throw a little something up, pun intended. Two months ago I wrote an analysis of Susan Sontag’s “Against Interpretation” where I argued that, rather than being opposed to all interpretation, as some believe, Sontag was instead opposed to “metaphorical interpretation”—to critics who interpret artworks metaphorically or allegorically. (“When the artist did X, she really meant Y.”) I thought I’d document a few recent examples of this—not to pick on any particular critics, mind you, but rather to foster some discussion of what this criticism looks like and why critics do it (because critics seem to love doing it).

The first example comes from Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art, in particular the exhibit “Destroy the Picture: Painting the Void, 1949–1962” (which is up until 2 June). One of the works on display is Gérard Deschamps’s Tôle irisée de réacteur d’avion (pictured above, image taken from here—I didn’t just stretch out a swath of tinfoil on my apartment floor). The placard next to it reads as follows:

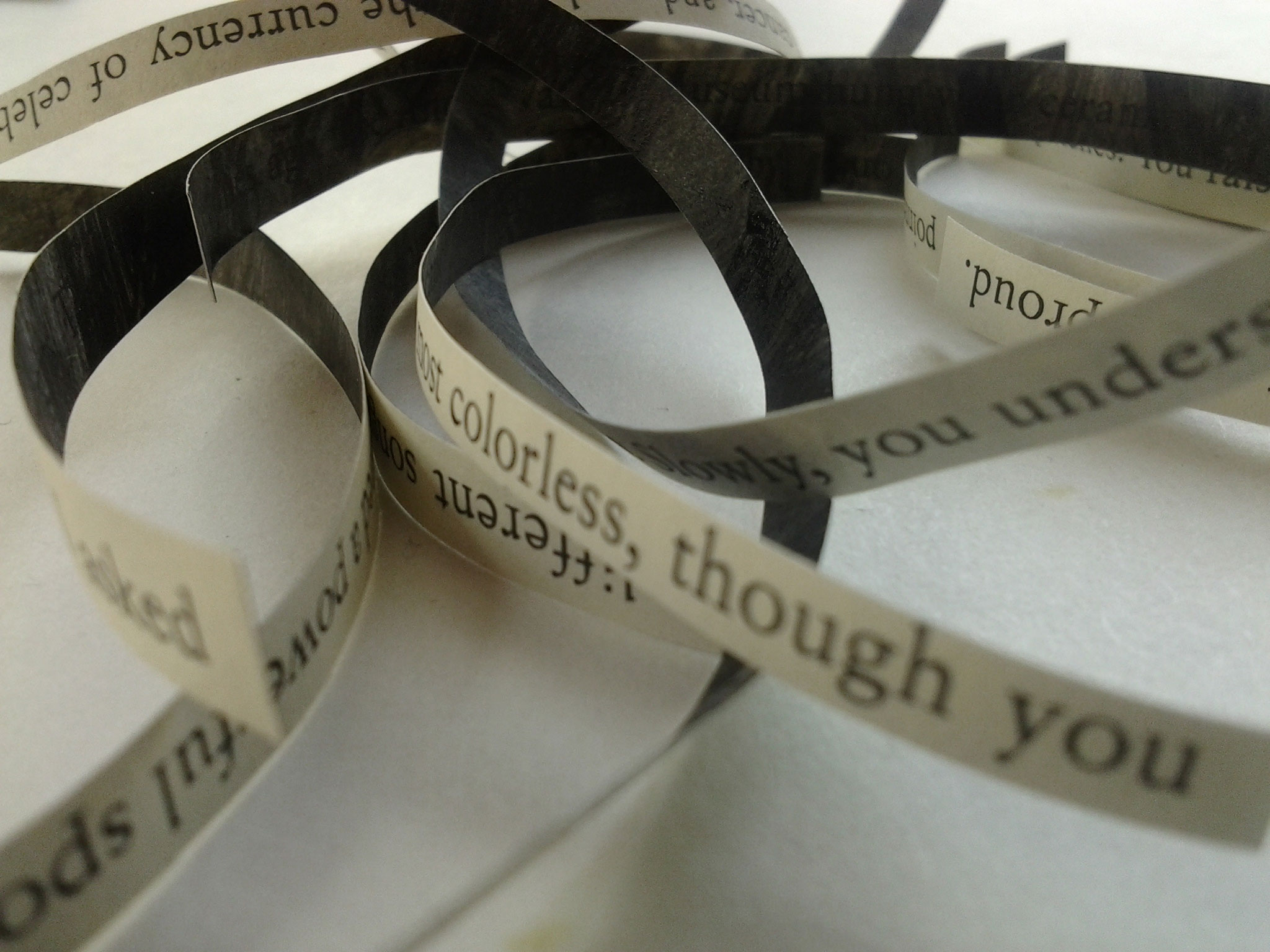

Another way to generate text #7: Gysin & Burroughs vs. Tristan Tzara

A while back, I ran a little series, “Another way to generate text.” The first one proved fairly popular, and I’ve been meaning to make more of them, but generative techniques haven’t been on my mind. However, my post last week, “Experimental fiction as principle and as genre,” generated a lot of text (haha), in the form of comments. Some people who chimed in questioned whether the Cut-Up Technique that Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs developed and used in the 1950s was ever all that experimental. Specifically, PedestrianX wrote:

I find it hard to accept this argument when its main example, the Cut-up, didn’t start when you’re claiming it did. I’m sure you know Tzara was doing it in the 20s, and Burroughs himself has pointed to predecessors like “The Waste Land.” Eliot may not have been literally cutting and pasting, but Tzara was.

This comment got me thinking about the role influence plays in experimentation; more about that next week. Today I want to address the point PedestrianX is making, as it strikes me as pretty interesting. Were Gysin and Burroughs merely repeating Tzara? Or were they doing something substantially different?

To figure that out, I decided to run through the respective techniques, documenting what happened along the way. Because if I’ve learned anything in my studies of experimental art, it’s that thinking about the techniques is usually no substitute for sitting down and getting one’s hands dirty.

If you want to get dirty, too, then kindly join me after the jump . . .

Experimental fiction as genre and as principle

A few years ago at Big Other I wrote a post entitled “Experimental Art as Genre and as Principle.” That distinction has been on my mind as of late, so I thought I’d revisit the argument. My basic argument then and now was that I see two different ways in which experimental art is commonly defined.

By principle I mean that the artist is committed to making art that’s different from what other artists are making—so much so that others often don’t even believe that it is art. As contemporary examples I’m fond of citing Tao Lin and Kenneth Goldsmith because I still hear people complaining that those two men aren’t real artists—that they’re somehow pulling a fast one on all their fans. (Someday I’ll explore this idea. How exactly does one perform a con via art? Perhaps it really is possible. Until then, I’ll propose that one indication of experimental art is that others disregard it as a hoax.) Tao visited my school one month ago, and after his presentation some folks there expressed concern, their brows deeply furrowed, that he was a Legitimate Artist—so this does still happen. (For evidence of Goldsmith’s supposed fakery, keep reading.)

Eventually, I bet, the doubts regarding Lin and Goldsmith will fall by the wayside. Things change. And it’s precisely because things change that the principle of experimentation must keep moving. The avant-garde, if there is one, must stay avant.

That’s only one way of looking at it, however. Experimental art becomes genre when particular experimental techniques become canonical and widely disseminated and practiced. The experimental filmmaker Stan Brakhage, during the 1960s, affixed blades of grass and moth wings to film emulsion, and scratched the emulsion, and painted on it, then printed and projected the results. Here is one example and here is another example. And here is a third; his films are beautiful and I love them. (The image atop left hails from Mothlight.) Today, countless film students also love Brakhage’s work, and use the methods he popularized to make projects that they send off to experimental film festivals. (Or at least they did this during the 90s, when I attended such festivals; I may be out of touch.)

Those films, I’d argue, while potentially beautiful and interesting, are not necessarily experimental films. As far as the principle of experimentation goes, those students had might as well be imitating Hitchcock.

Ekphrasis Flash

There used to be some CW pedagogy on here. Maybe there still is, I don’t know. Been away for a few days. My microwave died recently, etc. Anyway, I just remember a lot of people didn’t like it or something, so I thought I would go ahead and add some more.

Ekphrasis sounds like a skin disorder, but is actually when one medium of art attempts to relate to another medium. Like dancing about architecture or fucking about radishes, for example, etc. This can be a fructiferous exercise for a class (or workshop or, you know, just a group of people who like to write [It’s Ok to write just because you like to write, just like it’s OK to run just because, you know, you like to run or collect cats or whatever]). This exercise is ofttimes done with poetry and that’s OK I suppose, but I’d prefer you tried this exercise with flash fiction.

I’ll define flash fiction as under 750 words, since defining the genre any other way—by style, history, worldview—is reductive and wrong.

You’d probably want to show an example. An example actually cracks open the synapses. In fact, writing directly after an example (not with a lag) is a little teacher trick I’ll pass onto you. Sort of like your knowledge is lighter fluid and imagine your students have heads made of charcoal. Pour a little knowledge on their heads. Then toss in the match. The match is writing. This analogy is pretty forced, but it makes a shard of sense.

If you want to use the word “multi-media” on your salary review document, you could show this video, an ekphrasis by Pamela Painter:

Now you can say, “I like to use multi-media in my class…”

“In between surviving multiple point-blank-range assassination attempts and a failed kidnapping in which he emerged alive from the burning wreckage of a battleship his own air force had just bombed, Pibulsongkram decided that Thailand needed noodles that would advance the country’s industry and economy.” — Pitchaya Sudbanthad’s brief history of pad thai (and accompanying recipe) in The Morning News is the best writing criticism/advice I’ve read in months.

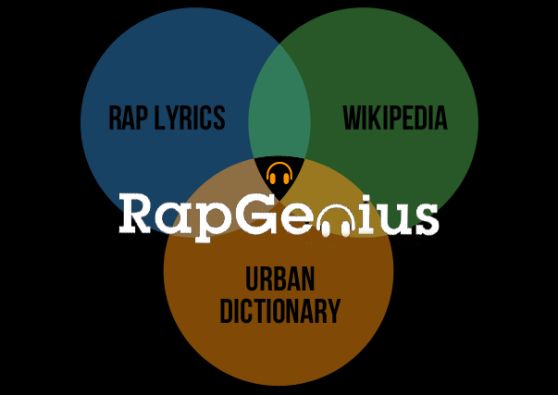

Rap Genius: A First Look

Someone grabbed me the other day. He wanted to talk about Rap Genius/Poetry Brain. He wanted me to talk about Rap Genius/Poetry Brain. I am good at talking—so I figure, why not? I mean this guy who asked me, he knew Barry Hannah, and I started right off the jump writing about Barry Hannah, and Hannah’s hospital visitation from Christ—which is just gorgeous and I would like to experience someday before my brain pops:

Someone grabbed me the other day. He wanted to talk about Rap Genius/Poetry Brain. He wanted me to talk about Rap Genius/Poetry Brain. I am good at talking—so I figure, why not? I mean this guy who asked me, he knew Barry Hannah, and I started right off the jump writing about Barry Hannah, and Hannah’s hospital visitation from Christ—which is just gorgeous and I would like to experience someday before my brain pops:

http://www.believermag.com/issues/201010/?read=interview_hannah_tower.

But then I had to cut the stuff about Hannah.

If this article were up at Rap Genius I could make the words “Hannah’s hospital visitation from Christ” into a link and when you clicked on it, then it would open directly to the part of the interview in The Believer where Hannah talks about Christ appearing in Hannah’s room at the old hospital.

Since it’s not, you have to go to the link and then scroll through the whole interview between Deep Water Hole Tower and Barry Hannah to find that moment of CHRIST appearing in Hannah’s hospital room, and the mountains behind him.

I don’t know much about Rap. I used to smoke Oregon marijuana and drive around as a skinny pale shit listening to my brother’s tape of “Too Short” in my brother’s old red Honda stick shift, driving through the hills of Portland, already making up crazy voices in my head to tell stories with, but not telling any of them, just listening to them making me crazy in my head. So stoned, and driving, and everything like a song. The whole world singing. Which was probably the best. The not telling them and just having them. I definitely didn’t believe Too Short and guessed he was just playing with voices in his head too. I didn’t think of any of it as factual, or having any larger implications, or that there was anything real to find out about. Which was my fault. I was dumb about rap. I was just another freaky weird kid driving around in a brother’s car, cologne in the console, getting drunk and stoned and looking at the sky. I don’t know why, but I want to put this link here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8Uee_mcxvrw. If this were Rap Genius I could put this in as a link in the word freaky up above. You’d just click on freaky and the video would open in a little window and you would still be looking at this thing I’m writing and you’re reading. I was dumb about life. I thought it was always going to sing and that I wouldn’t have to find out about life in order to use my voices. READ MORE >

I don’t know much about Rap. I used to smoke Oregon marijuana and drive around as a skinny pale shit listening to my brother’s tape of “Too Short” in my brother’s old red Honda stick shift, driving through the hills of Portland, already making up crazy voices in my head to tell stories with, but not telling any of them, just listening to them making me crazy in my head. So stoned, and driving, and everything like a song. The whole world singing. Which was probably the best. The not telling them and just having them. I definitely didn’t believe Too Short and guessed he was just playing with voices in his head too. I didn’t think of any of it as factual, or having any larger implications, or that there was anything real to find out about. Which was my fault. I was dumb about rap. I was just another freaky weird kid driving around in a brother’s car, cologne in the console, getting drunk and stoned and looking at the sky. I don’t know why, but I want to put this link here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8Uee_mcxvrw. If this were Rap Genius I could put this in as a link in the word freaky up above. You’d just click on freaky and the video would open in a little window and you would still be looking at this thing I’m writing and you’re reading. I was dumb about life. I thought it was always going to sing and that I wouldn’t have to find out about life in order to use my voices. READ MORE >

STEEP DREAM

ALL OVER THE NEW GESTURAL POETRY.

The Internet taught children to design themselves in a white space. Now, they are to create in that space. This burden. Laughter.

Appropriation was the first mimetic. The late remix, post-DJ culture of the 20whatevers sidevolved into a romance of the weird and origin-less. Repeat, offend, react. Horse eBooks, PT Cruiser, drugs, fetishes about whispering, shitting, looking into a new blank digital void. But it lasted only as long a generational breath. Weird Twitter rose and fell like a bird in a harsh wind.

The difference between a concept & a constraint, part 2: What is a constraint?

OK, back to this. In Part 1, I traced out how in conceptual art, the concept lies outside whatever artwork is produced—how, strictly speaking, the concept itself is the artwork, and whatever thingamabob the artist then uses the concept to go on to make (if anything) counts more as a record or a product of the originating concept. (This is according to the teachings of Sol LeWitt, as practiced by Kenneth Goldsmith.) Thus, we arrived at the following formulation:

- Artist > Concept > Artwork (Record)

Now, I’m not going to argue that every conceptual artist on Planet Earth works according to this model. But LeWitt’s prescription has proven influential, and continues to be revolutionary—because choosing to work with either a concept or a constraint will lead an artist down one of two very different paths. To see how this is the case, let’s try defining what a constraint is, aided by the Puzzle Master himself, Georges Perec . . .