August 22nd, 2010 / 12:12 pm

Craft Notes

Evelyn Hampton

Craft Notes

Giorgio Morandi

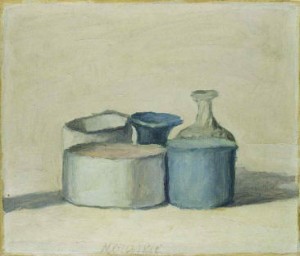

When a writer gets described as writing the same story again and again, the tone’s usually accusatory, like it’s a bad thing to be noticed doing. But here is this guy, Giorgio Morandi, who painted the same objects arranged in still life again and again. He got really into these objects and seeing what he could do, how he could render what was really there, and what was really there–light–was always changing.

Tags: Giorgio Morandi

Thanks for posting these, Evelyn. Morandi is a huge iterative influence in my small corner. If a writer, like a painter, is trying to SEE something, really see it, vision into touch, hearing into sensation, like Rothko or Reich or Bach or Orthrelm or Cezanne or Pavese, to name just a few, repetition will be the residue of those extended observations. To repeat oneself is only wrong if the motivation is to desperately or sanctimoniously hold onto something already grasped, not if the desire is to find something not yet understood in all the mystery that’s right in front of one.

“To repeat oneself is only wrong if the motivation is to desperately or sanctimoniously hold onto something already grasped, not if the desire is to find something not yet understood in all the mystery that’s right in front of one.”

BEE comes to mind.

I have been staring at this spit on a wall for a long time. I have been writing about this spit on a wall for a long time. I couldn’t write without a certain kind of repetition, reiteration.

repetition, more so than explanation, makes understanding possible.

on another note, objects like Morandi’s, carry a certain vibration inside them. i think it has to do with their stillness, their inertness.

the other night, i was sitting on a park bench inside a house, and i looked around me and realized i was sitting in the middle of a museum.

what attracted my attention most, however, was outside, on the porch of the museum:

an elephant ashtray with cigarettes arranged like pick-up sticks. these weren’t butts. these were long cigarettes, probably used for three shallow inhales, and then snuffed and arranged. what a magnificent sculpture! i stared at this, unpressed for time, and i thought,

what beautiful repetition.

Are you interested in an artist’s oeuvre or only his/her works individually? Are you interested in how the pieces fit together between works, or only how the pieces fit together within the work? How interested in being disinterested in art are you interested in being? If I saw one of Giorgio Morandi’s still lifes (wtf? what is the plural of ‘still life’? still lives?) and it blew me away, I might never want to see another in case it didn’t have the same effect.

It is strange, I suppose, that sometimes I might experience an artist’s art (whether it be music, painting, writing, whatever) and be compelled to consume it all and other times I desire to keep the single work I have experienced for myself and shun the others lest my original experience be tarnished.

But what do I know? I only paint cheese danishes.

I don’t appreciate Ellis’ work enough to comment on his repeating himself since Less Than Zero or American Psycho. But I doubt Thomas Bernhard kept writing more or less the same book with the same compulsive narrator—compelled as he was by compulsion—so that he could maintain a fan base or a career (not to suggest this is the same for Ellis as it might be, say, for John Grisham or Nora Roberts—I don’t really know). And Bernhard’s books just got more and more interesting as he navigated the same eddy of his mind. I don’t think Jackson Pollock or Clyfford Still kept at the same explorations over and over because the market demanded it, but because their interests (compulsions) let them do nothing else. Certainly the latter was true for Emily Dickinson and Henry Darger, wasn’t it? Or am I just romanticizing those artists I prefer?

I’m often more intrigued by the whole body of work (Beckett, Kafka, Stevens, Poe, Whitman, Stein, Woolf, even Shakespeare) than I am by the individual works. There are exceptions, of course (I strongly uphold Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, but little else of his writings, and Melville’s Moby Dick and Bartleby and Billy Budd, but none of the earlier novels or poetry, etc.). Again, perhaps I’m simply fetishizing my own notions of literary branding?

Thanks for posting these, Evelyn. Morandi is a huge iterative influence in my small corner. If a writer, like a painter, is trying to SEE something, really see it, vision into touch, hearing into sensation, like Rothko or Reich or Bach or Orthrelm or Cezanne or Pavese, to name just a few, repetition will be the residue of those extended observations. To repeat oneself is only wrong if the motivation is to desperately or sanctimoniously hold onto something already grasped, not if the desire is to find something not yet understood in all the mystery that’s right in front of one.

“To repeat oneself is only wrong if the motivation is to desperately or sanctimoniously hold onto something already grasped, not if the desire is to find something not yet understood in all the mystery that’s right in front of one.”

BEE comes to mind.

I have been staring at this spit on a wall for a long time. I have been writing about this spit on a wall for a long time. I couldn’t write without a certain kind of repetition, reiteration.

repetition, more so than explanation, makes understanding possible.

on another note, objects like Morandi’s, carry a certain vibration inside them. i think it has to do with their stillness, their inertness.

the other night, i was sitting on a park bench inside a house, and i looked around me and realized i was sitting in the middle of a museum.

what attracted my attention most, however, was outside, on the porch of the museum:

an elephant ashtray with cigarettes arranged like pick-up sticks. these weren’t butts. these were long cigarettes, probably used for three shallow inhales, and then snuffed and arranged. what a magnificent sculpture! i stared at this, unpressed for time, and i thought,

what beautiful repetition.

Obsession is rich food, not just for the artist but for the audience as well.

Are you interested in an artist’s oeuvre or only his/her works individually? Are you interested in how the pieces fit together between works, or only how the pieces fit together within the work? How interested in being disinterested in art are you interested in being? If I saw one of Giorgio Morandi’s still lifes (wtf? what is the plural of ‘still life’? still lives?) and it blew me away, I might never want to see another in case it didn’t have the same effect.

It is strange, I suppose, that sometimes I might experience an artist’s art (whether it be music, painting, writing, whatever) and be compelled to consume it all and other times I desire to keep the single work I have experienced for myself and shun the others lest my original experience be tarnished.

But what do I know? I only paint cheese danishes.

I know what you mean–it does seem possible to detect a difference between that sort of hermetic compulsion and performance–maybe it’s the different awarenesses of audience that happen in each, I’m not sure. I think there’s also a kind of compulsion for media attention, a compulsion to perform–probably Warhol is the most obvious example of this–where the performance is inseparable from what’s being made.

so nice that you posted this. there’s much to be said about morandi. he never dusted his objects, each growing a layer of fuzz, thus making his contours ‘fuzzier’ as decades moved on painting the same objects. he was known to mark the tables on which they rested, creating a record for each composition. also, his studio was a glorified closet of his sisters, whom he lived with for most of his adult unmarried life, such that he need permission to access it, which sort of turned painting into a sacred yet unreliable act.

That’s just the sort of thing I want to know about him or anyone.

By the way, Hank, are your cheese danishes anything like Thiebaud’s pies and cakes?

“Sacred yet unreliable”—feels right, looking at his paintings, thinking of the creative urge, even without the biographical tidbits.

I don’t appreciate Ellis’ work enough to comment on his repeating himself since Less Than Zero or American Psycho. But I doubt Thomas Bernhard kept writing more or less the same book with the same compulsive narrator—compelled as he was by compulsion—so that he could maintain a fan base or a career (not to suggest this is the same for Ellis as it might be, say, for John Grisham or Nora Roberts—I don’t really know). And Bernhard’s books just got more and more interesting as he navigated the same eddy of his mind. I don’t think Jackson Pollock or Clyfford Still kept at the same explorations over and over because the market demanded it, but because their interests (compulsions) let them do nothing else. Certainly the latter was true for Emily Dickinson and Henry Darger, wasn’t it? Or am I just romanticizing those artists I prefer?

I’m often more intrigued by the whole body of work (Beckett, Kafka, Stevens, Poe, Whitman, Stein, Woolf, even Shakespeare) than I am by the individual works. There are exceptions, of course (I strongly uphold Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, but little else of his writings, and Melville’s Moby Dick and Bartleby and Billy Budd, but none of the earlier novels or poetry, etc.). Again, perhaps I’m simply fetishizing my own notions of literary branding?

No, they’re just a reference to Thomas Pynchon’s “V.”

Obsession is rich food, not just for the artist but for the audience as well.

I know what you mean–it does seem possible to detect a difference between that sort of hermetic compulsion and performance–maybe it’s the different awarenesses of audience that happen in each, I’m not sure. I think there’s also a kind of compulsion for media attention, a compulsion to perform–probably Warhol is the most obvious example of this–where the performance is inseparable from what’s being made.

so nice that you posted this. there’s much to be said about morandi. he never dusted his objects, each growing a layer of fuzz, thus making his contours ‘fuzzier’ as decades moved on painting the same objects. he was known to mark the tables on which they rested, creating a record for each composition. also, his studio was a glorified closet of his sisters, whom he lived with for most of his adult unmarried life, such that he need permission to access it, which sort of turned painting into a sacred yet unreliable act.

That’s just the sort of thing I want to know about him or anyone.

By the way, Hank, are your cheese danishes anything like Thiebaud’s pies and cakes?

“Sacred yet unreliable”—feels right, looking at his paintings, thinking of the creative urge, even without the biographical tidbits.

No, they’re just a reference to Thomas Pynchon’s “V.”

Oh. Right. Slab, that catatonic expressionist. Had forgotten about him…

Evelyn, thanks for posting this. I’ve often wondered pretty much the same thing, that is, why is it that visual artists are given more license to explore and re-explore the similar constructions. Besides the artists already noted in the thread, Albers and Mondrian also pop to mind.

If one begins writing a story utilizing situation A, and characters X, Y, and Z, an endless number of possible stories can arise. Yet rather than fully explore all possibilities, the writer is pretty much expected to hone in rather quickly on ONE “story.” But sometimes it would be more refreshing to allow the writer license to publish together (whether within journal, chapbook, or book form) say, a dozen different variations of that story.

Part of the “problem” (is it a problem?) though is that visual art is “consumed” in a much different way than printed stories. Someone walking into a modern or contempary art gallery is probably more open to contemplate and, at times, be confounded by what they may see. Maybe I’m a lone nut, but as a visual art viewer, I don’t expect to “understand” everything I see. “Reality” is less fixed in the visual arts, and therefore it’s more permissable to hang multiple variations of that “reality” side-by-side on a gallery wall. One doesn’t walk into a gallery of Rothkos and think that any of them are “less real” or sub-standard just because they’ve already viewed a previous Rothko that derives from the same structure.

Yet because stories flow from words, and words are expected to maintain commonly understood definitions, most “readers” probably have less patience with stories that which they can not immediately understand. Since words have fixed meanings, stories are expected to have fixed forms. My guess is that if a reader is confronted with, say, four stories containing the same 3 characters and built upon the same premise, the reader would latch onto the first of those stories that s/he reads as being the “real” version– thereby relegating in their mind the subsequent stories to ‘less real” or out-take status.

Oh. Right. Slab, that catatonic expressionist. Had forgotten about him…

Evelyn, thanks for posting this. I’ve often wondered pretty much the same thing, that is, why is it that visual artists are given more license to explore and re-explore the similar constructions. Besides the artists already noted in the thread, Albers and Mondrian also pop to mind.

If one begins writing a story utilizing situation A, and characters X, Y, and Z, an endless number of possible stories can arise. Yet rather than fully explore all possibilities, the writer is pretty much expected to hone in rather quickly on ONE “story.” But sometimes it would be more refreshing to allow the writer license to publish together (whether within journal, chapbook, or book form) say, a dozen different variations of that story.

Part of the “problem” (is it a problem?) though is that visual art is “consumed” in a much different way than printed stories. Someone walking into a modern or contempary art gallery is probably more open to contemplate and, at times, be confounded by what they may see. Maybe I’m a lone nut, but as a visual art viewer, I don’t expect to “understand” everything I see. “Reality” is less fixed in the visual arts, and therefore it’s more permissable to hang multiple variations of that “reality” side-by-side on a gallery wall. One doesn’t walk into a gallery of Rothkos and think that any of them are “less real” or sub-standard just because they’ve already viewed a previous Rothko that derives from the same structure.

Yet because stories flow from words, and words are expected to maintain commonly understood definitions, most “readers” probably have less patience with stories that which they can not immediately understand. Since words have fixed meanings, stories are expected to have fixed forms. My guess is that if a reader is confronted with, say, four stories containing the same 3 characters and built upon the same premise, the reader would latch onto the first of those stories that s/he reads as being the “real” version– thereby relegating in their mind the subsequent stories to ‘less real” or out-take status.

“repetition, more so than explanation, makes understanding possible.”

repetition, more so than understanding, makes explanation possible.

explanation, more so than repetition, makes understanding possible.

explanation, more so than understanding, makes repetition possible.

understanding, more so than repetition, makes explanation possible.

understanding, more so than explanation, makes repetition possible.

Tim, how is a “body of work” intelligible – to the point of ‘intrigue’ – as a “whole”, except by reference to its “individual works”?

brand =? fetish – god

“repetition, more so than explanation, makes understanding possible.”

repetition, more so than understanding, makes explanation possible.

explanation, more so than repetition, makes understanding possible.

explanation, more so than understanding, makes repetition possible.

understanding, more so than repetition, makes explanation possible.

understanding, more so than explanation, makes repetition possible.

Tim, how is a “body of work” intelligible – to the point of ‘intrigue’ – as a “whole”, except by reference to its “individual works”?

brand =? fetish – god

There are plenty of exceptions, though. Stephen Dixon’s Interstate springs to mind. Also, Matt Bell’s Wolf Parts does this to some degree, permutating throughout. I think maybe the difficulty stems less from the authority of the first set of words and more from the way that stories work themselves on the brain, in that the process of inference, which relies more on the right hemisphere, happens after constructing the situation in the left hemisphere, so that going back over the same terrain with different purpose is challenging because it calls on the reader to uninfer or push aside the established inference. Which is sort of similar to what you were suggesting but not exactly. Also, more simply, in our everyday lives we encounter the same objects more than we encounter the same situations–situations are more variable and thus unrepeatable than objects.

There are plenty of exceptions, though. Stephen Dixon’s Interstate springs to mind. Also, Matt Bell’s Wolf Parts does this to some degree, permutating throughout. I think maybe the difficulty stems less from the authority of the first set of words and more from the way that stories work themselves on the brain, in that the process of inference, which relies more on the right hemisphere, happens after constructing the situation in the left hemisphere, so that going back over the same terrain with different purpose is challenging because it calls on the reader to uninfer or push aside the established inference. Which is sort of similar to what you were suggesting but not exactly. Also, more simply, in our everyday lives we encounter the same objects more than we encounter the same situations–situations are more variable and thus unrepeatable than objects.

Lower left painting: that shadow of the object NOT seen by us…

Lower left painting: that shadow of the object NOT seen by us…