Craft Notes

The Smooth Surface of Idyll

Happiness is not a popular subject in literary fiction, mostly because I think we struggle, as writers, to make happiness, contentment, satisfaction, interesting. Perfection often lacks texture. What do we say about that smooth surface of idyll? How do we find something to hold on to? Or, perhaps, we fail to see how happiness can have texture and complexity so we write about unhappiness. That is easier or for me, or at least seems easier. I am probably too comfortable going there, wallowing in this idea of darkness, suffering, unhappiness. Misery loves company. We are unhappy together.

I have been thinking about happy endings. I am always thinking about happy endings. I am always thinking about happiness.

Someone interviewed me and asked if I ever write happy stories or happy endings. I considered that question for days. I hear it a lot from people I’m close to as well. Almost every story I write is a happy story, a fairytale of some kind. Yes, you’ll find death and loss and betrayal and darkness and violence in my stories but there’s often also a happy ending. Sometimes, people are unable to recognize happiness because all they see is the darkness. I look at many of my stories and I see a woman who has found some kind of salvation after enduring seemingly unsalvageable circumstances, a hero who helps her to that place of peace, however incomplete that peace might be. The details change but that underlying structure, that fairytale, is often there. I’m as intrigued by happy endings as I am by the deeply flawed ways people treat one another even if I don’t quite know what to do with that.

Fairytales have happy endings. There are often lessons to be learned and sometimes those lessons are learned the hard way but in the end, there is happiness, at least in the fairytales I like best. My novel is, in its own way, about fairytales. It’s in the title so it is so! The story is about a woman who was living a fairytale and then she was kidnapped and her fairytale ended. Every story can usually be broken down to what it’s really about. I thought it would be interesting to start with the happy ending and see how that might unravel. It didn’t just unravel. The happy ending came all the way apart and then I had to figure out how to put the pieces back together, how to get my characters back to something resembling happiness.

I have mostly been thinking about happy endings because I started a new novel. I really enjoyed writing the first one, now out in the world trying to find a home, and I learned so much about pushing myself to write on the same project every single day and how to tell a story in long form and how to really slow the story down and give it the room it needs. The first draft of my first novel did not have a happy ending but I got feedback indicating a happy ending of some kind, however imperfect, was needed to make things seem less hopeless. I tried my best. As I started thinking about this new story that’s about a lot of things but mostly motherhood and surrogacy and a marriage of convenience and the incomplete choices we make when we’re too young to know we’re doing the wrong thing, I decided, no matter what, no matter how implausible it might seem, this book is going to have a very happy ending. I have no idea how I’m going to get there in a way that doesn’t defy credulity but I am going to try. Maybe it won’t be completely realistic and maybe that’s okay. Realism is relative. My fantasy life often feels quite real.

Recently, I went to see a show at the Indianapolis Museum of Art—a spectacular, brilliantly curated exhibit, Hard Truths, featuring the artwork of Thornton Dial. It’s hard to define Dial’s style—he works across many media—sculpture, drawings, assemblages, collage, much of it socially conscious, all of it gorgeous, passionate, visceral. Born in 1928, Dial grew up in the rural South and endured a great deal of economic hardship. He began working full time at the age of seven. He dealt with a great deal of racism, the untenable burden of segregation. The mark of these experiences can be seen throughout much of his work– torment, anger, sadness, pain, are all quite palpable. Unhappiness as a muse is not solely the purview of writers.

One of the things you notice about Dial’s art is the scale of it–most of his pieces are massive, taking up entire walls or floors, like he needs that much room to express himself. Oh and how he does. The scale of the pieces really reinforce the scale of the dark emotions influencing Dial’s art. That scale certainly made me feel grateful art exists as an outlet.

Trophies* (Doll Factory) is one of the first pieces in the Hard Truths exhibit. Dial was raised by women and the feminne influence marks a great deal of his artwork. In Trophies, the dolls are garishly painted, half dressed, many of them painted gold like trophies. It’s an interesting commentary on modern womanhood, perhaps even more interesting given that the commentary is being made by man. There is so much to look at in this piece, in all of Dial’s pieces. The level of detail is just amazing. I would have been content standing in only one of the many rooms of the exhibit because there was that much to see. The way the dolls are splayed across the canvas, how their breasts are bared, their legs splayed amidst the chaos of the rest of the assemblage, really sets the tone for the exhibit. As I moved on, I thought, “There won’t be any happy stories here.”

Throughout the exhibit, I kept noticing just how dark many of the pieces were, how the artist imbues his work with suffering, and also how these same pieces functioned as social commentary on race, class, gender, war, politics, all human concerns.

Throughout the exhibit, I kept noticing just how dark many of the pieces were, how the artist imbues his work with suffering, and also how these same pieces functioned as social commentary on race, class, gender, war, politics, all human concerns.

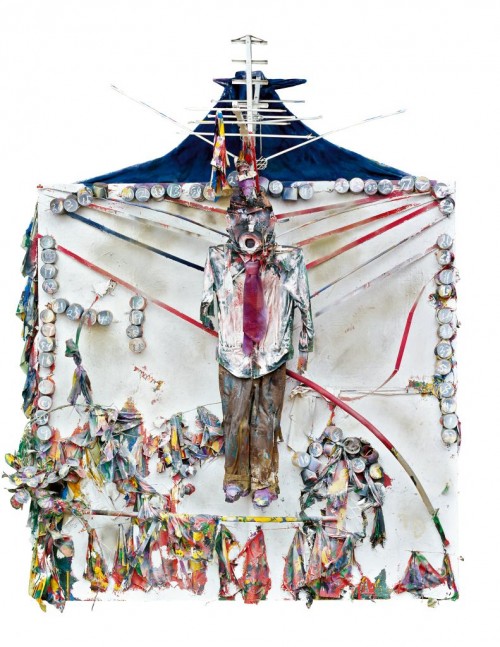

In 1993, Dial was interviewed by Morley Safer for 60 Minutes. He thought the interview was going to be about his artwork, but instead, Safer took the opportunity to do an “exposé” on how Southern black vernacular artists were being exploited by white art dealers. Dial was and felt ambushed and mislead and misrepresented by Safer and for years he carried a lot of anger about the incident, anger you can see in Strange Fruit: Channel 42. Dial’s work really gave me the opportunity to think about a piece of art as a narrative. In this piece, you see Dial as the man hanging in effigy, self as strange fruit, and the TV antenna (Channel 42 was the station that aired the Safer interview where Dial lived). There are lots of smaller details that you can’t see unless you are standing in front of the piece but they all work in concert to tell the story of Dial’s anger and frustration. He was angry for so many reasons but mostly because he thought this was going to be his big break into the mainstream art world, that finally his work was going to be recognized and it wasn’t. There’s a bitter humor to the piece that holds the weight of the artist’s disappointment. Dial also created another piece in response to the interview, this one, Looking Good for the Price, was much darker and angrier–the scene a slave auction, a macabre white auctioneer, everything abstract and quite tortured, the images spread across the canvas at awkward angles. Looking Good for the Price told another story about the artist’s anger, his sense of humiliation toward how he was mislead by 60 Minutes, another story about unhappiness, one seemingly without a happy ending.

The exhibit, as a whole, was overwhelming. As I moved from room to room, I kept thinking about how much pain Dial bleeds onto his canvas and how he works with that pain in really culturally savvy and responsive ways. Given his life story, it’s understandable that his work is a reflection of the difficulties he has experienced. I could not imagine that a happy ending would be possible.

The exhibit, as a whole, was overwhelming. As I moved from room to room, I kept thinking about how much pain Dial bleeds onto his canvas and how he works with that pain in really culturally savvy and responsive ways. Given his life story, it’s understandable that his work is a reflection of the difficulties he has experienced. I could not imagine that a happy ending would be possible.

And yet.

This explosion of yellow is Dial’s The Beginning of Life in the Yellow Jungle, an artistic musing on life and how it evolves. The assemblage has fake plants, flowers made from plastic soda bottles, a doll, serenely composed and because of how these elements are held together, with Splash Zone, you get the sense that everything is connected, both literally and figuratively.

This explosion of yellow is Dial’s The Beginning of Life in the Yellow Jungle, an artistic musing on life and how it evolves. The assemblage has fake plants, flowers made from plastic soda bottles, a doll, serenely composed and because of how these elements are held together, with Splash Zone, you get the sense that everything is connected, both literally and figuratively.

Room after room after room of the exhibit was filled with these massive art pieces, sculptures, drawings, most of them created using found materials and lived experiences. The last room of the exhibit though, was saturated in bright color. It was literally startling to enter the room and see… redemption, salvation, triumph, hope, happiness, a happy ending after a long, sorrowful journey. The pieces in the last room of the exhibit reflected Dial’s spirituality and how he overcome serious illness. Everything about the artwork was vibrant, almost ecstatic, in a much different way from the rest of the exhibit. It was inspiring and refreshing to see an artist willing to explore happiness as much as he was willing to explore pain, anger, darkness, unhappiness.

I have been thinking about happy endings.

Dawn Tripp’s Game of Secrets is, as you might imagine, a novel about secrets–secrets between the novel’s characters and secrets the author holds from the reader. Most of the plot hinges on Tripp doling out pieces of these secrets a little at a time. The story begins with an affair and a decades old murder–sex, betrayal, death–this is what many interesting stories are about. There’s some mystery to Game of Secrets but mostly, a man is dead and we know it even if we don’t know how he came to such a pass. The dead man was a father and an estranged husband and a lover. The book is about many things, but mostly it is about the aftermath of this man, Luce Weld’s, death and how, for decades, it affects many residents in a small New England town. We think we know who done it, Silas Varick, the husband of Ada Varick, with whom Luce Weld was having an affair but we can’t be sure. The story is told from multiple perspectives across several decades but the two main characters are Marne Dyer and her mother Jane Dyer who is the daughter of Luce Weld. Throughout most of the book, Marne is engaged in the fragile beginnings of a relationship with Ray Varick, Ada’s son and Jane is playing a game of Scrabble with Ada. In small towns, you can’t really get away from secrets and what made Game of Secrets so readable is that as a reader you could start to see that everyone knows a little something and Tripp made it easy to start to piece together what everyone knows in order to see the whole story. The premise of the book makes a happy ending seem nigh impossible because there are so many secrets that have been held close and tight for so long. In such an atmosphere, there’s bound to be unhappiness, sorrow, darkness and all of that is there but it doesn’t overwhelm the story. Instead, the awkwardness of these secrets creates a mournful tone. As I neared the end, I kept wondering how the story could have a happy ending for any of the people involved. Because I was invested, I wanted a happy ending for everyone. I wanted the people in this town to find their way out of the darkness, to reach that place of redemption, salvation, triumph, hope, happiness, a happy ending, after a long, sorrowful journey, even if I couldn’t see how that could be possible.

And yet.

There are happy endings in Game of Secrets for almost everyone involved even though those happy endings may not look the way we expect happy endings to look. Just before his death, a man recognizes his son. A daughter finally begins to understand the mother who has confounded her throughout her life, and that daughter is finally able to grow, able to show her mother kindness. A husband tells his daughter his wife was the only one, has always been the only one, without regret. A woman makes peace with moving back to her hometown and tries to allow herself to love. A man remains open to love even when he is pushed away. The happy endings in Game of Secrets, are subtle and incomplete but they are there and it works because happiness itself is often subtle and incomplete.

Sometimes, and especially as a writer, I feel like I have no idea what happiness is, what it looks like, what it feels like, how to show it on the page.

Hayden’s Ferry Review blogged a list of plots, story lines and such they are tired of seeing or that are, all too often, poorly executed. I’m sure every editor who reads this list will nod over and over because we all see the same kinds of stories and the same missteps. As an editor, I laughed and might have said, PREACH, to my monitor. As a writer, I was paranoid. I mentally reviewed my stories to see how many of those exhausted ideas I have written. It was awkward. One of the common themes in many of the overtired plots though, is a preoccupation with misery, disorder, dysfunction. Clearly, I am not alone in trying, perhaps struggling, to make sense of happiness and how to use happiness to tell an interesting story.

I have no problem with darkness, sorrow, pain, or unhappiness. I have no intention of straying from these themes. But. In thinking about the Dial exhibit and Game of Secrets, I wonder how we can complicate these themes that pervade fiction (and art) so often so that we can also achieve a more complete, complex understanding of happiness. Happiness is not boring or uninspiring if we don’t allow our imaginations to fail us. I want to believe there’s something to hold on to, even when dealing with the slick smoothness of idyll or joy.

*The Thornton Dial images come from the IMA website. If you’re in Indy, go to this museum. It’s wonderful. The idyllic image at the top is L’ile à Vache in Haiti. My mom took the picture.

Tags: Dawn Tripp, IMA, Thornton Dial

off the top of my head, i can’t think of one goddamn book or short story that i love with a happy ending. does anyone have one?

also loved seeing dial’s work here. exhibit looks amazing.

“Field Events” by Rick Bass. I teach it and my students always comment on how they kept waiting for something awful to happen and when it doesn’t it makes them feel confused or off-kilter or something. It’s a beautiful story, also.

oops that below was supposed to be a reply to this above.

What happened to some of the original comments on this thread?

Seems like people always reach for the worst generalizations when they hear, “happy ending.”

If you’re defining “happy ending” as, story-wrapped-up-with-a-cute-little-bow-and-everyone-lives-happily-ever-after, then I guess you’re right.

Maybe hope is a better word than happy.

I think there has been a post about happy endings (amirite) before, and I think I left a comment in which I mentioned Underworld as a (fantastic) book that has a happy ending. So yes, the ending to Underworld is happy.

Their Eyes Were Watching God has a very happy ending, and the protagonist has just killed her rabid husband. Amazing book.

Oh yeah, that’s a great example.

Great post, Roxane.

I don’t know many endings that are happy. I know happy narrators and shitty stuff happens to them. Or they make shitty stuff happen.

Which is like life: I think sustained happiness isn’t something that can be attained through any physical effort (“If I only had X I’d be happy”) It’s a state of mind, a perspective, a lens through which you view the world. You either decide to be happy (or positive) or you decide to be sad (negative).

I’d bet that if you followed what happened after every happy ending you ever read you’d find the main characters would eventually become disillusion with the happiness they’d been granted or sought out for themselves.

That last assertion seems kind of pointlessly mopey to me.

Naïve. Super had a happy ending I liked.

Great post. Great topic. The Winter’s Tale ends happily. In Search of Lost Time ends happily–well, radiantly; Marcel finally knows how he will write his book, though everyone’s gotten very old, so that’s not quite happily. Ulysses?

Oh! I’ve never read Villette, but I read the ending, I was pointed to it by a Google search on the word “nonnarratable” long ago. I think Charlotte Bronte was told to give Villette a happy ending. This is the narrator speculating on a happy ending, a rescue at sea:

“Here pause: pause at once. There is enough said. Trouble no quiet, kind heart; leave sunny imaginations hope. Let it be theirs to conceive the delight of joy born again fresh out of great terror, the rapture of rescue from peril, the wondrous reprieve from dread, the fruition of return. Let them picture union and a happy succeeding life.”

By not addressing you, the narrator is including you in the group of readers who know what she knows but needn’t say (that such rescue didn’t, won’t, happen). You’re on the very last page, so you know the interdicted but sketched return can’t happen in the rest of the book, and she knows you know that there’s no hope.

There’s a further twist of the knife in the very last words, which immediately follow the ones I quoted:

“Madame Beck prospered all the days of her life; so did Père Silas; Madame Walravens fulfilled her ninetieth year before she died. Farewell.”

We’re returned to mortality by this unjust distribution of fates: the uselessly long lives and happy endings of the wrong characters.

*

ps– I don’t think I’ll read the Hayden’s Ferry post. I know reading mediocre fiction is wearying, I’ve done it, but I’m not sure it makes sense to separate out one strand of the fiction, the plot, and hold it to blame. I’m sure all the “tired” plots mentioned there, whatever they are, could make great works. I doubt that avoiding a list of forbidden plots will make anyone’s writing great.

Didn’t intend as mopey. Just meant when people get exactly what they want that doesn’t mean the story is over. Life goes on. Things change. More often than not, peoples perception of what they want in the first place tends to change when they get it.

Great post, Roxane, and thanks for the intro to Dial –

Big Big fan of Kara Walker btw . . . (why did I say that? . . . )

A favorite memorable-reading-moment re: happy endings is on the last page of Chilly Scenes of Winter:

“I got my way,” he says.

“You did,” she says.

“A story with a happy ending,” he says.

And I felt that it was not “he” speaking with “she” but “me” speaking with “Ann Beattie”.

Makes me think of Buddy Wakefield and Andrea Gibson. Often heartbreaking poems strung up with hope.

Makes me think of Buddy Wakefield and Andrea Gibson. Often heartbreaking poems strung up with hope.

[…] and editing stuff ) 94% self deprecation and 6% moderate bragging)). Speaking of, I wrote about happiness and happy endings for HTMLGIANT today. Also, I think I forgot to mention I have a story, of sorts in Tarpaulin Sky […]

[…] and editing stuff ) 94% self deprecation and 6% moderate bragging)). Speaking of, I wrote about happiness and happy endings for HTMLGIANT today. Also, I think I forgot to mention I have a story, of sorts in Tarpaulin Sky […]

I don’t know about the happy ending, per se, but I am a fan of the redemptive lift. You know, that little up-tick at the end of the narrative where you know the character has reached some sort of turning point in his mind, made a decision, come to peace with something. Two books I read recently that have this sort of “soft happy” ending are Game of Secrets by Dawn Tripp and The Bird Sisters by Rebecca Rasmussen. But I think this is a far cry from a trumped up “happy ending.”

Austen’s novels end happily: with good marriages, which make present or even constitute a vision of fertility and regeneration in and in spite of worlds of pettiness, mendacity, avarice, and incontinence generally. Forster does the same with ‘comedy’, the vision of life in and through a happy marriage.

This vision doesn’t stand over against decay and death, as though they’d been annihilated by the happiness in a happy family, but rather, alongside the ‘tragedies’ of limitation and failure and mortality.

—Symposium 223d

[…] posted this at HTMLGIANT the other day and it is really good. Good things to think […]