Some of the most singular moments in understanding come on as if being shook: a presence entering the body unto some new consideration of how that entrance might occur. One kind of a map of a version of one’s self might be determined by considering among the terrain of the body a series of approached organs; objects imbibed, in what order, how one’s own output is affected; what is out there; what is. Seeing does this. Language, more indirectly, does this, too: entering as symbols and networks of orchestrations. Some strings of language, as well, leave in their wake a total reinvention of creation as an act, iconing on the map of self, and many selves; updating or widening or recalcifying what any kind of words can, could, or should do.

I can remember with unusual clarity the feeling in me the first time I read David Foster Wallace’s “Mister Squishy.” It was published under the name Elizabeth Klemm in the 5th issue of McSweeney’s in 2000, but by the time the magazine reached my hands I’d already heard on the Wallace listserv that this rather lengthy piece of fiction could only ever be written by him; there could have been nobody else. I was already a rabid Wallace freak; I’d pretty much begun writing fiction as a direct byproduct of reading Infinite Jest, and since then become obsessed. I read this story, long as perhaps 3 normal stories, on a futon in a house in one sitting under a skylight with legs crossed, already ready to be lit. And yet, the particular instance of “Mister Squishy,” even having then been well versed in a way that somehow placed the author’s presence in my daily thoughts (which has not since then stopped), rendered in me that the first time something different even than what I’d been ready to expect: some odd confabulation of provocation, confusion, inundated awe; a feeling rare not only for any kind of language, but particularly for a shorter work. This was something singular beyond even the already neon body of Wallace’s work in constellation, and in particular, beyond the confines of what a story as a “story,” or a novel even, or text as text, traditionally operationally assists to construe.

Since then I’ve read the 63 pages of “Mister Squishy” at least a dozen times. I’m not sure even still I can begin to wholly how to parse the innumerable levels of its moves, using tactics and employments that continue shifting with each reconsideration and further study in the way a Magic Eye painting might if it could get up and walk around: a kind of high water mark of contained language and ambition, since then, now ten years later, still uncontested in the ways of invoking the uninvocable, the void. It is a station, I believe, should be reexamined; it is, in many ways, a kind of key to a beyond, both in the content of the story, and the method of its opening a new kind of affect in languageground, one that still has yet to be, these years later, fully inculcated, or because of time’s way, even unpacked.

“Mister Squishy” opens in midst of something already underway: “The Focus Group was then reconvened in another of Reesemeyer Shannon Belt Advertising’s nineteenth-floor conference rooms.” This kind of opening, wherein the reader is inducted into something forces him to assume a certain amount of momentum elapsed prior to the text’s initiation, not as backstory, but as present motion clipped into already underway, is a device not unfamiliar, but often misplaced or mistakable in other fictions. Here the method seems to set you down into a record of no sound, as what comes after this motion opener is not at all the kind of action one would expect having snipped into: a test panel being performed with a focus group for a major market research corporation.

Wallace’s narration for the remainder of the opening graph concerns itself with his by now patent Wallaceian descriptive eye, which somehow manages to operate both clinically and with odd persona flourishes to create an equally spartan and familiar-without-demanding-familiarity sense of air. Of all of the particularities of Wallace’s voice that make his megasentenced, highly aware narration affective and so wanting in the reader is this seamless balance of the voice, almost like the kind of beautiful human robot we find in children’s films: it should have no emotion, because it is machine, but it cannot help but leak some warmth in through its frame. Here it is even more subtle than in other Wallace texts: “Bottled spring water and caffeinated beverages were made available to those who thought they might want them.” Refreshing, yes, if queerly common, a disarmingly simple kind of calm, inside the plastic den: it is like being given a tour of a new home by a friend you have known a long time and never gotten quite past a certain formality with; it wants you to settle in without particular discomfort, and yet there are these rooms to see.

The first 7 pages of the story then proceed in primarily this opening voice, describing in selective, explicit detail the fourteen members of a marketing focus group, all men between the age of 18 and 39, who for the most part are rendered by certain peculiarities about their appearance or demeanor. Other descriptions reduce the men to percentages of how many of them of the whole share certain sociological traits. There is little reference to actual names, and for the most part the characterization, the tolling of the “human” quantity present seems glassy, glancing, if peppered still with Wallace’s strange homey/alien flares that create quiet bursts of seemingly sourceless warmth. This makes sense, given the focus of the story’s concentration: marketing research, but also carries with it a kind of double front, as if we are waiting for the wall to turn reflective, be a mirror.

A pair of short (for Wallace) single sentences in the first 8 pages also are separated from the larger graphs, letting two twin hiccups stand alone, suggesting, in other models of singling out of ideas in paragraphic structures, that these items should carry heavier weight, and yet each of them seem oddly devoid of character beyond the way they render air both populated and unused. On the first page, the second graph, in full, reads: “There were more samples of the product arranged on a tray at the conference’s table’s center.” At the point of this pronouncement we don’t even know what ‘the product’ is yet, which in closer looking at that sentence as it stands alone among the larger fields seems, if you let it, terrifying, while also, blank. On page 5 (and here, as I will do from now on, I’m referring to page lengths and numbers by their appearance in the later version of the story as it appears collected in Wallace’s final fiction collection, Oblivion): “Traffic was brisk on the street far below, and also trade.” Again, a singled away graph that seems to offer nothing but an abstruse pawing at the air surrounding the building we are so far housed in, which as the story goes on, will never in present moment action camera away from beyond a edgeless lip of locality for the building, as if the building could be in any city large enough to have a building of such size, oddly monolithic as not even other neighboring buildings are described.

A pair of short (for Wallace) single sentences in the first 8 pages also are separated from the larger graphs, letting two twin hiccups stand alone, suggesting, in other models of singling out of ideas in paragraphic structures, that these items should carry heavier weight, and yet each of them seem oddly devoid of character beyond the way they render air both populated and unused. On the first page, the second graph, in full, reads: “There were more samples of the product arranged on a tray at the conference’s table’s center.” At the point of this pronouncement we don’t even know what ‘the product’ is yet, which in closer looking at that sentence as it stands alone among the larger fields seems, if you let it, terrifying, while also, blank. On page 5 (and here, as I will do from now on, I’m referring to page lengths and numbers by their appearance in the later version of the story as it appears collected in Wallace’s final fiction collection, Oblivion): “Traffic was brisk on the street far below, and also trade.” Again, a singled away graph that seems to offer nothing but an abstruse pawing at the air surrounding the building we are so far housed in, which as the story goes on, will never in present moment action camera away from beyond a edgeless lip of locality for the building, as if the building could be in any city large enough to have a building of such size, oddly monolithic as not even other neighboring buildings are described.

Rigorous attention in these opening pages is also paid to Terry Schmidt, the focus group’s “facilitator,” who instructs the group on the surveying method for the panel, responding to the afternoon’s product of their concern: Felonies!, a high end chocolate desert that intends to create its own niche in the dessert snack food market by embracing its indulgence in the midst of a trend of diet foods and self-conscious consumption, manufactured by a brand known as Mister Squishy. These details are presented almost without clear reasoning as to why so much detail is necessary as to the nature of the focus study, even being important enough as object to provide the text’s title with its name, and yet in Wallace’s voice is carried forward by its pleasurable exactitude and voicing. It is equally obsessive, benign, and seemingly puffy, like a plastic bag being slowly blown into with a mouth; each reread I’ve done on these sections, after knowing how they will play out (which is, mostly, not at all, in way of action, but all potential and in paused thrall), has evoked further sublimity in the somewhat cryptic meandering of the buried information, like little cells that take their own air and eat it and stay full, coupled with a teeming rubber silence that builds between them, on the edge of equally collapse and an implosion even knowing later (kind of) what they will entail.

Near the end of these 7 pages of market-speak brick laying, before the major first shift in perspective that will come on the next page in the same utterance of flow, Wallace leaks a parallelism in the narration of Schmidt’s persona and function as a human and the leading of text’s as object, in its manner, unto what as we continue might open larger light: “The whole problem and project of descriptive statistics was discriminating between what made a difference and what did not.” The sentence comes among one of many in the same mode, a placid straight-face that over the course of the whole text never truly breaks. This early in the work we could take this to mean a more common idea of language making, such that any detail is an important detail, by its inclusion, even if some push us further than others in the mix; as more such slight intentional slips emerge between author and himself (not the reader, because this is an organism rather than a fable), we will begin, I believe, to find something more akin to the opposite: that anything is the thing itself; is not constructed metaphorically, but in orchestration of reflection of itself seeing itself, and thus has almost no quality beyond what it is not. As we continue, this idea will continue to be slightly adjusted and rolled against in other hidden and undirectly applied threads, all of which, in a certain mode of consideration, could be said to be tooling not with the characters or scenarios contained on paper, but in the nature of the reader’s, and the author’s, heads: a breaking of the third wall without acknowledging the third wall, and w/o regard for the old idea that you should not interrupt some narrative “dream,” though among the meat of such a dream so undreamed it feels not dreamlike but equations, machines in purring, a song made out of symbols. Where the blur fits onto the person, I’ve felt in all my time in brain with this text, is less a question of reflecting the human, or even directly altering the human, but installing in the head a little blip or tiny mirror that over time, in me at least, causes longer term station: here, then, the rendering upon the “human element” is not a question of conveying emotion, or even direct affect, but by infecting me with what I do not realize I am being infected by because it is in me and so becomes me and is there. For all of those who’ve championed Wallace’s wishing to portray the human, to use emotion in a text, this effect in “Mister Squishy” is perhaps one of the greatest examples of how this semblance is not actually a function of empathy, narration, identity, or drama, but more a product brought on by evoking something that otherwise does not exist, and installing it in the function of the reader without them even fully knowing why: a power entered in the flesh, unto the flesh: no parable, or index, but a twinning, a sum towards the zero, made of activated mechanical work.

“You’re trying somehow both to deny and affirm that the writer is over here with his agenda,” Wallace said to Larry McCaffery, “while the reader’s over there with her agenda, distinct. This paradox is what makes good fiction sort of magical, I think.”

And so now: on Page 13, without visual demarcation beyond new paragraphing, and without a switch in tone, the text then abruptly but fluidly alternates to a second present moment setting of the story: what is going on outside the building that focus group convenes at the same time as they convene. Which is: a “figure” appears in “free climb” on the building’s face, outfitted with Lycra, GoreTex, and suction cups. The figure begins moving up the windows of the building without clear intent or cause, in a “manner of climbing [that] appeared almost more reptilian than mammalian, you’d have to say.” Wallace uses only one average sized graph to introduce the figure, as well as the crowd that begins to observe him from below. The next graph immediately again returns to the conference room, leaving this instance as a thin, black jump cut in the progression, glimpsed on and left wide; this toggling will occur at various points throughout the remainder of the explication of the story’s primary focus on the focus group.

From here on, under the new veil, even as the pacing, ad-language, and weirdly poised corporate speak continue, we are suddenly blanketed with a latent building terror: we don’t know what the two modes have business about together, or why so casually we’ve been dunked into the other frame, like a sporadic appearance of a black screen slipped into our usual program. On first read, one must assume the figure outside the building will collide with something inside, the scenes will merge. The assumed potential splay of this impending collision (which, spoiler: will never come; at least, not physically) sends both a backdraft through the lengthy set up, of what had been and would be coming, between glass, and an increasingly taut string of pull-me-forward, wherein, throughout the pacing, we are flinching for the bang. This bang, however, is semantic, and therefore, even up until today as I am typing still inside me will recoil; if anything, too, on rereading, once we know, this duality is weirdly even more alarming, because in never fully playing out or directly corresponding, we are not allowed to touch: the run off, then, runs off of page of the book and is left to spill into the mind. More than a simple “human” ramification product, and more, too, than sound-based language without clear frame wide-open unto all, the split is a shriek that keeps repeating, and will repeat without end.

Our return to the description of the focus group’s outfitting in the next graph is not wholly left to be carried by the sudden latent paranoia of the figure; at the end of the graph, on page 14, the fabric of the speaking shifts again. In the last third of this next graph we are suddenly dropped from what seemed a third person omniscient voice, into a first person omniscient, again without cursor blinkage between modes: “…he also had an over-shoulder bag he kept in his cubicle. I was one of the men in this room, the only one wearing a wristwatch who never once glanced at it. What looked just like glasses were not. I was wired from stem to stem.” Here, now, implanted in our speech stream, is another figure, one who, unlike the newly rising climber, had been in our midst undetected (even speaking to us) all along. Again, this consideration is only briefly chewed at, signaling a more complicated string of locomotion already underway, something perhaps more sinister or to-be deep-reaching than we’d previously only just now been updated to, right beside us; and then again the mode shifts back to the speaking manner we’d been acclimating into, if slightly veering in its aim. In fact, this will be the only invocation of the “I” inside the text; making it, in repetition of the whole, even more alarming as a narrative tactic, and also as a wire in the house.

What we now are turned to, again, all seeming quite casually in pace and tone, is a more in depth consideration of who will now even more concretely emerge as the central definitive human presence in this text, Terry Schmidt, via the nature of his building infatuation and obsession with coworker Darlene Lilley. Schmidt’s make up is patently pathetic; he lusts for this woman he can not have, all rendered in Wallace’s more familiar-from-previous-work sense of longing parsed with his position’s inflated market-speak. In fact, we find in waves that Schmidt in many ways is so intrinsically infused with his employment, that in certain ways they are becoming, within him, semantically confused. A short graph immediately after the revelation of the “I” states: “Terry Schmidt himself was hypoglycemic and could eat only confections prepared with fructose, aspartame, or very small amounts of C 6 H 8 (OH) 6, and sometimes he felt himself looking at trays of the product with the expression of an urchin at a toystore’s window.” Here Schmidt is portrayed as so disarmed by life’s work he’d not even able to consume the object he’s undertaken a life in pursuit of employ to manifest unto the public. He is separated from his life-object by a kind of glass, like the glass that separates the focus group from awareness of the climber, that bisects his life and its object-laid conceit.

Later, this persona blur between the self and the product is even more concretely and directly weighed:

[Schmidt] would look at his face and at the faint lines and pouches that seemed to grow a little more pronounced each quarter and would call himself, directly, to his mirrored face, Mister Squishy, the name would come unbidden into his mind, and despite his attempts to ignore or resist it the large subsidiary’s name and logo had become the dark part of him’s latest taunt, so that when he thought of himself now it was as something he called Mister Squishy, and his own face and the plump and wholly innocuous icon’s face tended to bleed in his mind into one face, crude and line-drawn and clever in a small way, a design that someone might find some small selfish use for but could never love or hate or ever care to truly know.

This moment is one of the more plain Wallace-qua-Wallace moments in the entire text; it and other moments like it in emotional texture are all confined within the body of Schmidt, the neuter, the gimp. The familiar language-algebra and mechanisms of the up front market-saturated objectivism we’ve been presented thus far, again in the presentation of relation between man and glass is briefly, slightly relieved, if here still in its own way creating another kind of glass, one back with reflective paper, forcing the self onto the self. In seeing himself in the glass by which he is surrounded head on, Schmidt is not only anesthetized figuratively, identifying with his overlord and payor, but commented upon there inside it as inhuman, a caricature of emotion, clever, yes, but “in a small way.” The self reflects the self the self chooses to reflect, and that is who he is, to him. Each person hiding “the repulsive nest of moles under their left arm” (Schmidt’s) or perhaps more dark, complex desires (Schmidt’s), which as a matter of fact end up being quite central to this text’s center, slightly hinted, and soon to come further into light.

Please forgive me: Terry Schmidt, 5 letters and 7 letters. David Wallace, 5 letters and 7 letters; the latter “having emerged from years of literally indescribable war against himself.” (Said quote appearing later in this same book re: David Wallace’s appearance in the story “Good Old Neon”).

“Advertising is not voodoo,” the narration states in perhaps the shortest sentence in “Mister Squishy” some pages earlier than Schmidt laid bare. Want is manifested not by mere dictation, but by inspiration, by becoming. This corporate building of our setting is devoted to the creation of ads not only designed to make someone believe they want something, and so do, but also in such believing, whether taken on as self or not, becomes a session of the self: it is, and is. These are poses. Minute orchestrations of self in carrying the self. It is seen, perhaps less self-consciously, also in member of the panel: “the sleeves of the sweater were carefully pushed up to reveal the forearms’ musculature in a way designed to look casual, as if the sweater’s arms had been thoughtlessly pushed up in the midst of his thinking hard about something other than himself” (28). Some selves less mentally ripped than the statedly above-average-intelligent Schmidt might be less of themselves by not succumbing in the image, or might in other ways, actualized, be more. Both are true and neither is true. The glass looks the same from either side, though what is behind it shifts.

It is perhaps important now to recall, too, that all of this, is being told to us by the covertly implanted “I,” our secret member of the panel who seems to know all of both the ins and outs of the workings of the office, and the panel orchestration, and the panel members’ lives, and the goings on outside the building: a seated member in the fold, who, in knowing all things in all people, seems like god; who is in our midst, who is armed with something that may or may not seem ready to destroy us all; who does not exist; who is creating this whole amalgam in his nowhere; who is anyone; the reader. Again, we do not know.

The notion of god does arise here elsewhere, however, in passing, in Schmidt’s elucidation of his concurrently running and pummeling want for this woman Lilley, who consumes his mind at some points to the point of her taking a dual overriding face behind the face of Mister Squishy’s crushing load. “Marriage,” thinks the thinker in the mind of Schmidt’s mind, “…seemed every bit as miraculous and transrational and remote from possibilities of actual lived life as the crucifixion and resurrection and transubstantiation did, which is to say it appeared not as a goal to expect to ever really reach or achieve but as a kind of navigational star, as in in the sky….” Schmidt’s only motivation to go forward, beyond the dogday shit of money-motives, is beyond amorphous, is not real, is no part of him, but some high map; a thing that in the same breath is manifested in the terror of his nightly channel surfing looking for something better, afraid of missing one channel’s signal for another’s, never seeing anything to see, but want and want and want and never have. The blank is the thing. The metaphor is not a conduit of some unreal, but a falsity misplaced.

This abjection is reflected in the growing of the crowd that congregates below the building where the figure outside climbing the glass continues to rise. They watch, wanting the something, living in the reel. This is reflected in the narration’s admission that the very market research taking place here must be orchestrated in such a way, always, to approve: as the nature of market research is that by the time one has spent enough to know that what they are researching is “resoundingly grim or unpromising,” it is too late to turn over; the job would be lost. The job is to authorize the job. The absence of the god is to demand the god.

…the whole huge blind grinding mechanism conspired to convince each other that they could figure out how to give the paying customer what they could prove he could be persuaded to believe he wanted, without anybody once ever saying stop a second or pointing out the absurdity of calling what they were doing collecting information…

What are we talking about here. We’re talking about talking, about talking about self hiding the self: this is writing, in a soft object, a book in replication. What happens to Wallace later. We’re talking about writing. We’re talking about a body who concerned himself with the image of man rendered in words. We’re talking about a man who ended his life with his hands he’d used on other days to write, or masturbate, or eat. This story was written by that man in the mind of another mind he tried on wanting to be someone else, to other people: Elizabeth Klemm.

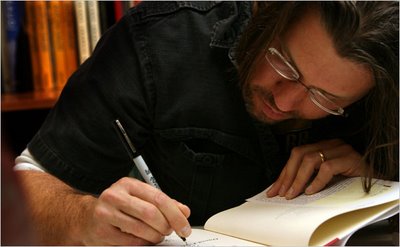

The one time I saw Wallace read and do a Q&A I stood up asked him something goofy about Klemm; he seemed to shrug it away, as the name itself had been a suit he’d tried on and could not hide his own body using any longer after, an aborted attempt to enter else. He’d accepted this. He was him through him to who. We’re talking about writing about writing about a thing that does not exist in anything but in traces. We’re talking about talking about talking about it, it, it, it, it, it, it. Mister Squishy. Oblivion.

“That it made no difference,” the narration states, re: the focus research, and therefore Schmidt’s ultimate pursuit. “None of it.”

Oblivion.

The object at the center of this text is, remember, Felonies!, a chocolate candy made to be so rich it made the rich feel richer. Wallace could not eat sugar later in his life.

Today outside my window where I am writing the light is touching at the curtains at the tip of the top of the V between the spreading white shim as if it is licking at my face to hit my eyes and change their light.

The figure on the face of the building inside the text continues to rise. He reaches a point on the building and begins to suction himself in a quasi-human contortion where he affixes himself and begins to inflate sections of his body, rising out in balloon, becoming disfigured from the person already reptilian but of the human, and changing shape before the rapt and potentially endangered crowd below, whose awareness of being potentially endangered does not preclude them to check out of the scene. They can not bring themselves to not watch the human inflate, disfigure, again in sections that supplant themselves between the by now throat-throttingly paced an still-even but with now backlog on the backlogged writing that has begun to seem not about marketing or want or event at all, but about something wormed behind the worming worms, something in the blood of the false body of the creator, behind the machine, who is there and never there, and never, now, here, either, but in these words, which might be more than any other mode and might be nothing but a sold thing, burnable, a machine, if a machine that reflects, glassly, god. A god concerned, at the end of the day, herein, with the consuming of a chocolate.

Felonies!, the narration explains, is a “Shadow product,” meaning “one that managed to position and present itself in such a way to resonate with both” “the Healthy Lifestyles trend’s ascetic pressures and the guilt and unease any animal instinctively felt when it left the herd.” To conflate life (good health) and death (demapping). To do this, and having admitted the knowledge that the market research industry props itself up by always greenlighting itself by manipulating its own characteristics to such an extent that the right is always right, a projected marketing strategy for Felonies! could go the way of what the narration says “was known in the industry as a Narrative (or, ‘Story’) Campaign),” which operates by reflecting the uselessness of the data onto the creator, vis a vis, in the example here of candy, “say, a tyrannical mullah-like CEO,” who, the Story would tell the buyer, forced the market-poor object through the system because of his own want for such a luxury, an item demanded in himself beyond all means, however fluffy, and thus, via, again, the Story, use the idea that we all know by now that marketing is goobered, and this is just an object that was wanted by the god. The god deigned to put the chocolate in our big mouths so we could have it: a gift. Is the theory. Pleasure. Is what, say all this goes right, Mister Squishy, the brand, might do. Theoretically. If this goes forward, though the narration will not be around to lead us to such end. We are going to be abandoned. Each thing is contained in the paper of its time.

Among all this, too, I’ve yet to more than poke at, is Schmidt’s further complicating ploy–rendered in past-relayed action, “back story,” here almost dreamlike and algebraic at the same time: totems–to sabotage the whole thing by creating and injecting Ricin, a lethal toxin, into a few iterations of the chocolate object’s hollow center, and letting such damage leak into the market, ruin the product’s reputation, and its grasp: to in effect cripple the object, by indirect murder, destroying, if we maintain the Mister Squishy head over his head, his own self, making him a weapon and a ruin at once. Following a brief but rather brutal description of Schmidt’s trying to make emotional headway in his life by taking place in a Big Brothers / Big Sisters program, via which his false child enters a mall and disappears, Schmidt is described actually synthesizing the poison, bringing death fantasy into his true life. Explicit instructions on how to create the toxin are laid out like a recipe, as if supplying Anarchist Cookbook style kill-them-all-kill-yourself screed buried deep here in, countless levels folded in the fold. The death drive goes on even still inside the crippled, malformed ID of body. Demapping the false map.

In my room now the light at the window has retreated to just a slim glow along the tipmost point of the inverted V. My hands look yellow, chalky.

I am in here.

You are in where?

This fantasy will not occur. Schmidt’s ploy, as far as we see, is unemployed, at least onscreen. Schmidt’s mind defeats itself. In another fantasy of Lilley, in which he fucks her, to which he masturbates, simulating the simulation, Schmidt can’t help his fantasy-self from saying Thank you Thank you to her, for fucking him inside his pathetic imagination, making “him wonder if he even had what convention called a Free Will.” Even his private creation is manipulated by his faith’s absence in his creation against his will. And yet, he ejaculates regardless in the motion of the want of the creation to go on. The act is flesh and not flesh; no child is made.

There is further implication as to Schmidt’s coming fate, outside of the Ricin deathseed, and his sperm-gush. The very act of the method for taking all of this focus group information and whittling it down into something that can corroborate what is needed, the narration describes, “meant doing away with as much as possible of the human element, the most obvious of these elements being the TFG faciliators” (Schmidt), as “with the coming digital era of abundant data… were soon going to be obsolete”). These prongs of the text, bending inward toward no full absolution, suggest for our hypothetical hero, of no hero, to become rendered to the void: separated even from the him of him, unto the ending, regardless of his ploy. Obsolescence rises.

The last reference to the inflation of the climber appears 13 pages before the remainder of the text ends. Though it is not directly stated, the climber has inflated himself into a version of an enormous, air-filled Mister Squishy, “large, bulbous, and doughily cartoonish,” affixed for no apparent reason on the face of the building in the gathering and the light.

There was no coherent response from the crowd, however until a nearly suicidal-looking series of nozzle-to-temple motions from the figure began to fill the head’s baggy mask… the face’s array of patternless lines rounding to resolve into something that produced from 400+ ground-level US adults loud cries of recognition and an almost chlidlike delight.

Nearly suicidal-looking.

Almost childlike.

Recognition: There I am.

Mirrored in, the people behind the glass are never made to realize the occurrence, or respond. Whatever action is detailed by the revelation of the “I” figure, who has been further made, in one of a few sparse footnotes, to be prepared to enact an act of fake barfing onto the research table, an act that never fully plays itself out, despite implication, unto its prognosis in the future of the Felony! or Schmidt or Schmidt’s Ricin or how god knows what god knows, or what will become of what god does. Though one thing, to god, is clear: “We were all of us anxious to get down to business already.” But we don’t: the focus group, despite all the lead in of prognosis method, formality, consensus-making necessity explication, etc., the summit does not occur. Not here.

This story was first published in 2000. Eight years later, now more than two years ago, which I can not believe, that amount of time, being that time, the creator, in his own parlance, demapped, if merely to reconvene in another conference room on this floor, or another floor, or unto the glass.

Oblivion.

Oblivion.

The future, is, however, given a name. “The market becomes its own test,” the narration states, re: the method of the future of this research, yet to come. “Terrain = Map. Everything encoded.” In this way, “Mister Squishy,” as a map, contains perhaps more of a landscape set outside itself than any particular node of what it concerns itself with so explicitly, confined.

This is how the human is human: this text is not a portrait, nor an equation, nor even a system or device, a sound, but a conglomerate of expressions expressing nothing each beside the other in a syndicate that by its presence alone forms a map. This text’s expression, considered solely, in each instance, is of other hands, ones beyond demapped ones. Wallace, as creator, invokes a terrain that is not even present in itself, that wants to hurt itself, that wants and can not say it, that wants its creator, that wants. Beyond Wallace. Beyond the Mister Squishy Corporation. Beyond Elizabeth Klemm.

“We hadn’t spent that much time with David since he was a small boy,” Wallace’s mother said. “Once they grow up and leave home you see them, of course, and you visit, but you don’t spend hours and hours with them.”

This story ends, in one sense, at its beginning. We close with one of the figureheads of the research circuit elucidating further methods as to the creation of the aura of the object of the dessert, which will perhaps occasionally be a thing some human puts into their mouth, suggesting that the way to rid the corporation of its facilitators, to demap Schmidt, the human element in the data, would be to show them something outside of themselves. To exhibit to them, beyond the inherent way already done day in and day out, that their position is not only potentially workable by any, but also fails to do anything but complicate some truth. An amorphous unrevealed overorchestrated truth in the first place. Ruining the ruin.

To end them on their own will, then, the figurehead says, “All they needed were the stressors. Nested, high-impact stimuli. Shake them up. Rattle the cage.” The figurehead “poked glowing holes in the air above the desk” as he presents this. He presents it to a younger, up and coming CEO, a future one to walk in his airs. The figurehead asks the boy to dream up these false stimuli that will kill the human, to: “Impress the boss.” “Anything at all.” If we want to know the figure inflating into Mister Squishy over the crowds is a product of this, and or the forthcoming implanted fake barf maker is instead or is as well, we must assume. We must assume, too, our own elucidation of the end, as unto this end, the boy can do nothing but look on, “his mind a great flat blank white screen.”

We are left here in the white of the page. At the bottom of the last page of the text a final footnote, Wallace’s little incessant infiltrating thought inside of thought, appears, visually, after the fact, relegating what is essentially, by now, sidebar information. “Mister Squishy”‘s last words, if we read out of order, as would visual narrative, are: “playing with his little pink toes.”

The yellow light at the top of the window now is wholly gone. Though in the sky further than the window through glass the sky itself is still pale and has a light that sits on every inch in one even, dimming way.

What is set up in here after could go on if there were more words, but what is left is from many angles so diffuse, and at the same time so exacting, that what terror wells up, in repetition, is more frightening than any deathblow of summation, illustration, finger to the throat.

If we remove the human element from this story (i.e., Schmidt is let go from employment, unto himself) without a human element the prognosis of the coming day is the replacement of the human with the machine, the human left to pilot himself toward the center of a nothing. What is human about being human is that anything that is human is not human and to say such is the void of the void.

If we do not remove the human element from this story (i.e. Schmidt is not let go, yet, though it is foretold one day comes regardless, and anywhere, in here, he hardly has a head) without a human element the prognosis is, perhaps, Ricin (death). Perhaps time goes on a little longer and the decision becomes not suicide but murder. And what becomes anyway is the same mode: the cake goes on the market, and the cake sells, or does not sell. The cake, regardless, somewhere down the road, ends in the same way it begins: a question that is answered in the instant that it is uttered. A god without a god’s shape. What comes out of this end is any end.

Where this leaves us, post-creator, post-holding the paper open in my lap again until next time, I don’t know. I do know. I don’t want to. I want.

Tags: david foster wallace, Mister Squishy, Oblivion

Yesterday, when it was my turn to pick the music at work, instead of putting on ABBA, I plugged in the BoCD of Brief Interviews with Hideous Men. The squawking of my coworkers was unbearable so I told them, just one story please. I put on “Forever Overhead” and waited for some temp-esque actor to stumble along. What I got was Wallace. This may not seem out of place, an author reading his own stuff, but to me to have his voice in a source outside of the interwebs was soaring. DFW read like I had never read the story before, but I knew that it was right. Pace, control, his Midwest perfect pronunciation. He was like a tuning fork for the cadence. What I thought about after the story finished, “Hello,” was how could I ever sound that removed from and yet wonderfully emotional in my writing. Blake, I’m glad you like DFW. Not because I do too, but because you ask questions that I’m just beginning to form and you see things I can barely make out on the horizon. I brought up the BoCD because, behind everything written/read there was emotional map. Deep seeded feelings that more than rooted but took over while reading. Thanks for posting a new node of connection.

This is 180 times better than anything I’ve ever posted here — a chance to simulate the experience of being in your brain as you read. I’m happy to have started my day with this essay.

i just went to the dentist and my mouth is all fat and furry with novocaine, drooled a little on the keyboard.

this hits all the right brain spots:

‘For all of those who’ve championed Wallace’s wishing to portray the human, to use emotion in a text, this effect in “Mister Squishy” is perhaps one of the greatest examples of how this semblance is not actually a function of empathy, narration, identity, or drama, but more a product brought on by evoking something that otherwise does not exist, and installing it in the function of the reader without them even fully knowing why: a power entered in the flesh, unto the flesh: no parable, or index, but a twinning, a sum towards the zero, made of activated mechanical work.’

much appreciated Kyle

Blake, this is incredibly engaging, thank you for sharing such double immersion. I just reread this story this past weekend, so this couldn’t arrive at a better moment! Much more to say, and in more depth, as it all catches up to me in a freer moment. Cheers!

Yesterday, when it was my turn to pick the music at work, instead of putting on ABBA, I plugged in the BoCD of Brief Interviews with Hideous Men. The squawking of my coworkers was unbearable so I told them, just one story please. I put on “Forever Overhead” and waited for some temp-esque actor to stumble along. What I got was Wallace. This may not seem out of place, an author reading his own stuff, but to me to have his voice in a source outside of the interwebs was soaring. DFW read like I had never read the story before, but I knew that it was right. Pace, control, his Midwest perfect pronunciation. He was like a tuning fork for the cadence. What I thought about after the story finished, “Hello,” was how could I ever sound that removed from and yet wonderfully emotional in my writing. Blake, I’m glad you like DFW. Not because I do too, but because you ask questions that I’m just beginning to form and you see things I can barely make out on the horizon. I brought up the BoCD because, behind everything written/read there was emotional map. Deep seeded feelings that more than rooted but took over while reading. Thanks for posting a new node of connection.

“What is set up in here after could go on if there were more words, but what is left is from many angles so diffuse, and at the same time so exacting, that what terror wells up, in repetition, is more frightening than any deathblow of summation, illustration, finger to the throat.” Yeah! It’s a good case for the story as a faster-burning Infinite Jest, the way each frayed end makes the big picture feel more and more how life does in the long game. This was a headrush and a lot of fun.

i just went to the dentist and my mouth is all fat and furry with novocaine, drooled a little on the keyboard.

this hits all the right brain spots:

‘For all of those who’ve championed Wallace’s wishing to portray the human, to use emotion in a text, this effect in “Mister Squishy” is perhaps one of the greatest examples of how this semblance is not actually a function of empathy, narration, identity, or drama, but more a product brought on by evoking something that otherwise does not exist, and installing it in the function of the reader without them even fully knowing why: a power entered in the flesh, unto the flesh: no parable, or index, but a twinning, a sum towards the zero, made of activated mechanical work.’

I’ll be moving on to Oblivion once I’m finished with Brief Interviews. I’m bookmarking this page so I can go back to it. Thanks for this.

Blake, you have, once again, reminded me what it means to be a fucking human being. This morning, when I woke up, I planned on eating my Peanut Butter Crunch and then killing myself, but because of your post I have decided that not only is life worth living, but that this world would be a much worse place were you not around to bless us with your inspiring and downright awesome missives. So I say thank you, as does my wife and my two sons, especially my two twin sons, Rusty and Dusty, whose Christmas has been saved, for my absence would have meant no Harry Potter lego sets since my wife is a vengeful witch who sees in the face of my boys the face of the man who raped her. God bless.

You are strong for supporting two kids who aren’t yours.

Oh, they’re mine.

Sometimes I dream about a novel length Mister Squishy. I want it so badly.

Almost as badly as I want Benno von Archimboldi to be real.

according to his answer when i asked about Klemm, there was a whole cycle of stories written as Klemm. i don’t think any of the others ever saw the light of day. he seemed to think they failed. who knows, maybe one day.

thank you L., that is a lot to say.

BIwHM has a pretty insane range of styles and emotions. Forever Overhead is probably as sentimental as he gets, but it also never pushes the line so hard that it feels forced. man, i need to pick up that CD, i didn’t realize he was the one that read on it.

http://www.change.org/profile/view/156542

it’s really a beautifully done post that makes me ache and want to open. much like the story. thanks.

Dodes’ka-den

This contributes as much as the story itself. Another example of Wallace giving rise to something spectacular through you. Keep it up. He’d be happy.

Oh, that’s where you’ve been

i apologize for the terseness of this comment in lieu of such a lengthy posting…

…but i couldn’t stand Mister Squishy the couple times i tried to read it. to me, it felt experimental in a way that failed, a kind of impermeable stream-of-consciousness that didn’t expect to be understood. jargon without a sense of generality. pyrotechnics without choreography.

this post, however, your apparent in-awed-edness has given me pause, and i will revisit it when i can, and will attempt to read the same story with the same abandon.

I’m a day late, school got me breathless and backed up, but wow oh wow what a thought provoking essay…I really enjoyed reading it this morning while drinking my coffee…I recall you mentioning “Mr. Squishy” a while back and I made mental note to check it out but never got around to it…this post has raised my intrigue meter to eleven…Christmas break will include (in addition to the completion of a certain magical manuscript) a reading and consideration of “Mr. Squishy,” for sure.

Please, come on. This is a obsessively hyper-analytical post by someone who apparently spent too much time in the academy, about an obsessively hyper-analytical author who spent too much time in the academy. One gets the impression, in wading through so much bad writing, that ultimately you’re talking about nothing. Anyway, could you summarize your point, or DFW’s point? Or would that defeat the idea– the idea being that jargon IS the post?

“–traditionally operationally assists to construe.” Say what??

“using tactics and employments” Uh, Blake, WHO is using the tactics? You? DFW? Might want to look closer at that sentence.

“–a new kind of affect in languageground,’

Uh, very affected, yeah. I agree.

And so on.

Bad writing layered upon bad writing, put forward with a pseudointellectual air about it.

The question is why you’d want to follow DFW on his path of hyper-aware obsessiveness? It seems a path toward insanity. For the writer, it’s a dead end, in that it narrows the literary art, moving the writer ever farther away from the potential audience. Which might be the point.

Is there any real knowledge conveyed about, say, the corporate world, or the society we live in, by his story? Is it not instead solipsistic pseudo-knowledge, which has to be conveyed with the jargon of the academy?

(Sorry to crash the party– er, and I’m not ‘hating’ on you by posting this, but instead offering a contrary viewpoint. I’m of the school which believes that clarity of language expresses clarity of thought.)

You know, “King” Wenclas, if you had ever written a sentence worth parsing, I’d be ready to engage you in an argument about this matter. Since you haven’t, I guess the only thing to do is write a dismissive post of your post the way you wrote a post dismissive of Blake’s, in which I summarily dismiss the subject (and intense analysis of this or any subject) and then declare that good analytical writing would reduce an expression that required 6000 words to a summary and a “point.”

(Here in parenthesis, I’ll pseudo-apologize, while not really apologizing and meantime self-aggrandizing. Is that clarity enough?)

I tracked down some of Wenclas’s clear deathless prose, if you’re interested in learning about our critic. Here is an excerpt:

=====================================

“It’s indirect,” Fake Face said to his gang at their Veronica Street headquarters. “The police wouldn’t act on their own. Someone’s prodding them.”

The main members of his gang sat around him. His sourfaced gun moll girlfriend known for her ambition. Several obedient toughs. In black-and-white clothes, the cynic, Jake Pol. The rust-red arched room around them looked archaic; baroque.

“Would the D.A. be that crazy?” Jake Pol wondered out loud.

=======================================

I’d take half a million bad postmodern experiments, seven terrible plain Richard Bausch knockoffs, twenty-three Jennifer Weiner chick lit novels, and the entire text of the phone book over shit this poorly written. Shame on you, Wenclas. You’ve misled us all with your talk of improving literature. I thought maybe you were making something interesting. I was wrong.

“[go] beyond the confines of” = ‘transcend the limits of historically determinate capacity of’; “a story as a ‘story'” = ‘narrative considered from the perspective of story-telling’; “traditionally” = ‘as a matter of historically-effective consciousness’; “operationally assists to construe” = ‘works to enable to build; is an efficient cause in building’

–

“what a story as a ‘story’, or a novel even, or text as text, traditionally operationally assists to construe”; the “what” = x

Therefore, ‘the history of the story-telling aspect of narrative shows narrative to work to enable the building of x‘.

and

“[Wallace’s novella (?) Mister Squishy goes] beyond the confines of [x].”

Therefore, ‘Mister Squishy transcends the limits of the historically determinate capacity of narrative, considered in its story-telling aspect, to work to enable the building of x.’

—

(“text as text” makes the proposition so widely considered as badly to muddy the waters of the claim for Mister Squishy, in my view. The quoted snippet is not gibberish, though it’s a grand – a perhaps unhelpfully sweeping – claim to make for any single piece of writing.

For a writer to demand effort is not an art crime. For a reader to make, of the fruits of her or his lack of effort, a claim of comprehension – particularly egregiously: a dismissive claim – is.)

thank you deadgod; nicely done.

and in regards to sweeping: this text as text sweeps. i don’t think it is a fallacy to include all in comparison, because i allow all text as potential affect, or try to.

This post is really uncalled for. How dare you attack someone else’s writing and post it in ridicule. And doing so ananomously. The guy’s got a right to an opinion. Blake’s prose often takes lofty leaps. He’s going to trigger this response in some people. I’m sure he’s used to it.

I don’t mind. Not at all. Fire away. My “pop” writing is experimental, but experimental in an entirely different way from DFW’s experimenting. Please separate my fiction from my ideas. I argue for clarity of writing, but also realize new prose has to be readable in new ways from, say, a Hemingway. What I aim for is what a Georges Simenon was able to accomplish: creating a world, an atmosphere of sounds and smells, with a phrase or two. It’s the direct opposite of what Foster Wallace tried. The truth is that less is more. One can give a thousand examples of this. Look at how British pop-rock music of the 60’s mutated into the overwrought junk of the 70’s. The early Beatles were effective because their music was stripped down to its essence. “No Reply.” “Baby’s in Black.” “I’ll Get You.” Etc etc. The emotion is right there. Contrast this with the pseudo-intellectual posturing of Emerson Lake and Palmer, who layered more and more onto their febrile songs, to less and less effect.

********************

What we’re talking about with opposition to DFW’s brand of postmodernism is more than being merely dismissive. It’s a difference of world views. It’s a difference as well of what one expects of literature.

With my prose I may very likely write bad literature. (Some of it anyway– though some of the other stories I’ve posted at my “Pop” blog are right to the point.)

The truth, though, is that “Mr. Squishy” is also bad literature. You may want to call hostility toward the reader a good thing. I don’t. The first task of the writer is to communicate. To get the reader interested in the first place. Most people aren’t going to last, with DFW, past the first page. There’s no pace; no attempt to establish a quick narrative line. DFW is being self-indulgent. It’s what they call in sales “TMI”: Too Much Information. I guess one can find nuances of meaning, as Blake did, in the mass of verbiage. I didn’t. I’d also guess that 90% of those who read Blake’s post didn’t have a clue what he was talking about, but are afraid to admit it. The power of the herd mindset.

But anyway, thanks so much for putting me in my place, “deadgod.” When you have to write an academic paper explaining a sentence, then someone isn’t very effectively communicating.

Have a happy holiday.

(I plan to soon discuss, on my main blog, instances of literary history when there were similar differences in worldview, and what the writer can learn from them. Young writers especially shouldn’t be following the dead end path a postmodernist like DFW will take you on. Just my own opinion, of course.)

[…] 3. King Wenclas Returns to HTMLGiant Comments Section, Spars with Commenters, Finds an Unlikely Defende… […]

Less is more. Less is less. When problems arise, it isn’t style but execution that is the source.

“When you have to write an academic paper explaining a sentence, then someone isn’t very effectively communicating.”

No, it just means that Blake wasn’t talking to you. I didn’t read past the seventh or eighth paragraph, though, because “tl;dr.” I’d be more inclined to read the whole thing if it was in print. Or if I’d read the story in question.

Mittens, that sentence you’re not sure exactly how to parse, beginning with “Among all this, too, […]”:

I’m guessing that the main obstruction is the – I think: lousy – way its punctuation is typed.

Look at these dashes: “ploy–rendered” and “totems–to sabotage”. The dash after “play” is an open-parenthesis ( ( ) and the dash after “totems” is a close-parenthesis () ) (the parentheses including a genuine hyphenated ‘compound’ word: “past-rendered”, which Blake glosses as unhyphenated “‘backstory'”).

So: ‘Among all these things I’ve talked about superficially, there is also Schmidt’s stratagem, which complicates the plot further, and which is written as “back-story” in a simultaneously almost dreamlike and algebraic way (that is, totemically), the stratagem being to sabotage the whole thing by manufacturing Ricin and injecting it […].’

–

It’s a dense and aggressively thought-thread-unspooling blogicle, which expresses an interest only intermittently in sign-posting coordination of its thought-web – perhaps deliberately obfuscatory, perhaps only accidentally so.

And, as I think you’re saying, there are word and syntactic choices a red-penciled scribbler would challenge: “patent” for ‘patented’, for example – a cliched way of saying ‘characteristic’; and perhaps Blake wants to mean ‘inimitably Wallaceian’.

But, also ‘as you say’, why not?? Carelessness: always bad. Adventurous attempt to limn the thought-stream of an impassioned mind in enthusiasm about art: good enough for the likes of Beckett (on Proust) and Kenner (on Pound and modernism) – two great books. I think, in the way of a rough-but-ready blogicle, that that’s the literary category of Blake’s Wallace, what, appreciation.

I also think your point against Wenclas’s limited scope of reception is a most useful take-away nugget, and Hemingway/Barnes and Fitzgerald/Joyce are just the right illustrations.

(You do know the story about Hem punching Djuna to the ground – twice – one night in the street outside a bar in Paris?

What’s the name of the narrator/protagonist of The Sun Also Rises? – the ‘wounded’ man? . . .)

Rad essay, Blake.

I don’t think David Foster Wallace’s prose is ever anything but precise – certainly difficult as a whole to get through, but never anything but clear.

I do think Karl has a point, though, with this essay – I’m not really criticizing the essay – it’s a blog post, and obviously written with much thought and passion, so maybe it’s unfair to criticize a lack of editing, but it’s been put out there, and since Karl brought it up, maybe it’s worth talking about. I never got the sense that the essay felt academic, though, I think that’s the wrong accusation, but I wonder about certain choices – a few easy examples – why ‘shook’ instead of ‘shaken’ in the first sentence? Why not ‘in medias res’ versus ‘in midst of something already underway’ or how to parse the sentence that begins: “Among all this, too, I’ve yet to more than poke at, is Schmidt’s…” These are little things, though, but I think it’s fair of Karl to suggest that the essay is, at times, unclear, while I acknowledge that written language is never completely precise (even in what Karl probably would consider clear prose), and that the more sophisticated the argument, the harder it is to be precise without difficulty.

Maybe the essay could have been edited in such a way to convey Blake’s interpretation rather than obfuscate it (versus DFW’s prose always being clear, despite sometimes tricky syntax.) That’s not to say that Blake was trying to ape DFW here at all, only to say that I think Karl’s right, at least in suggesting that there are some clarity issues with Blake’s essay. BUT, it’s a blog post, not an academic paper (I’d argue that the best academic prose is always clearly written, even in the prose of writers like Derrida or Irigaray), and that obviously in Blake’s passion to communicate a reading of a complicated story, the prose isn’t always crystalline, but I’d argue with Karl that that doesn’t make Blake a product of the academy, just a passionate reader with something to say.

And, Karl, I’d ask why does it matter? So Blake’s essay isn’t always clear; so DFW’s prose is difficult. That doesn’t mean there isn’t room for your kind of writing, too. Hemingway was certainly experimental (at least in In Our Time) but that doesn’t discount the awesomeness of Nightwood. Gatsby is as modernist as Ulysses and certainly one is easier to read than the other, but I’m glad we have them both.

[…] so… I’m a David Foster Wallace fan… but, uh… […]

Mittens, that sentence you’re not sure exactly how to parse, beginning with “Among all this, too, […]”:

I’m guessing that the main obstruction is the – I think: lousy – way its punctuation is typed.

Look at these dashes: “ploy–rendered” and “totems–to sabotage”. The dash after “play” is an open-parenthesis ( ( ) and the dash after “totems” is a close-parenthesis () ) (the parentheses including a genuine hyphenated ‘compound’ word: “past-rendered”, which Blake glosses as unhyphenated “‘backstory'”).

So: ‘Among all these things I’ve talked about superficially, there is also Schmidt’s stratagem, which complicates the plot further, and which is written as “back-story” in a simultaneously almost dreamlike and algebraic way (that is, totemically), the stratagem being to sabotage the whole thing by manufacturing Ricin and injecting it […].’

–

It’s a dense and aggressively thought-thread-unspooling blogicle, which expresses an interest only intermittently in sign-posting coordination of its thought-web – perhaps deliberately obfuscatory, perhaps only accidentally so.

And, as I think you’re saying, there are word and syntactic choices a red-penciled scribbler would challenge: “patent” for ‘patented’, for example – a cliched way of saying ‘characteristic’; and perhaps Blake wants to mean ‘inimitably Wallaceian’.

But, also ‘as you say’, why not?? Carelessness: always bad. Adventurous attempt to limn the thought-stream of an impassioned mind in enthusiasm about art: good enough for the likes of Beckett (on Proust) and Kenner (on Pound and modernism) – two great books. I think, in the way of a rough-but-ready blogicle, that that’s the literary category of Blake’s Wallace, what, appreciation.

I also think your point against Wenclas’s limited scope of reception is a most useful take-away nugget, and Hemingway/Barnes and Fitzgerald/Joyce are just the right illustrations.

(You do know the story about Hem punching Djuna to the ground – twice – one night in the street outside a bar in Paris?

What’s the name of the narrator/protagonist of The Sun Also Rises? – the ‘wounded’ man? . . .)

the dash after “ploy”

Generally, a fair line to draw for called-for/uncalled-for distinction. But a major exception, in my view, would be when the target employs this tactic her- or himself.

Here, tributebandonym is just doing what Wenclas did – putting a fragment on a pedestal for the purpose of condemnation – and doing it explicitly in reply to Wenclas’s scorn, not gratuitously.

Also, the criticism itself, in Wenclas’s case, is material: ‘I don’t get it, so it’s “bad”, “pseudointellectual” writing.’ Is that logic not, in fairness, a ready target for sarcasm?

[…] Frosted Mini-Wheats and read a Blake Butler essay. Stared past Apple symbol on iMac and sensed contentment. Laid on bed and saw moth crawling on […]

this essay, an able if sometimes precious effort whose stylistic homage to wallace needs another going over, shows some things.

1. wallace was first and foremost a critic

2. fiction attempting big r romantic vision via analysis is doomed to repetition of maxims founded on advances in computer science, cognitive science, and to a lesser extent linguistics–our philosophical basement

3. our arts situation is very poor when our best authors fail to find value in living, preferring to insist what little products we are of western civ–sorry, but this is wimpy (not to say that dfw’s suicide; i pretend to know nothing of the inside of the man’s head)

4. in mr squishy and in the essay about it, masturbation may have other, unstated significance

5. masturbation has its uses

Our best writers must find value in living? . . .why??

“Most people aren’t going to last, with DFW, past the first page.”

What makes you say this? And how can you know that most people won’t? For me Wallace reads very easily. Certainly he’s easier than most difficult poetry. How has Paradise Lost survived if “most people” can’t even read a page of Wallace? I think you are severely discounting the average reader’s patience.

As an example – prof Kathleen Fitzpatrick recently taught an undergraduate class at Pomona wherein the students read through Wallace’s major works in a semester, and all indications were that the students loved it. And unless you want to argue that this arbitrary group of California undergrads constitute some exceptional hyperacademic bunch of overzealous book-munchers, I think it’s likely that you’re unfairly restricting the range of any given reader’s tastes.

it’s always a good idea to seek clarity with alacrity

i’d say more ‘mass-disturbation’ than the former

readers tend to be alive

And they all require that their best writers confirm the value of being alive?

i’d argue the archetypal source material for every story ever written is derived amidst experiencing life.

I’ve got to say, for someone who seems to be attempting it at great length, you really suck at communicating.

I agree with several of your points, and I read through your posts very carefully, as a result, to give them their full credence. This site is very academic, for instance. From what I understand it’s run and populated mostly by MFA graduates or soon-to-be’s, some teachers here and there, I think, and in general since that is the type of person which comprises the indie lit world, and this happens to be an indie lit site, I’m not terribly shocked by this, nor do I find it something terribly worth commenting on.

You make many other points I could see reality or truth in, but too often I wonder either why they are points which need to be made now, or why they are points which need to be made in this way.

Less polemic.

Living seems like one of those things that is a foundational value. If you don’t value living, I imagine it is hard to value much else.

Writers here are always looking at literature through the narrow prism of their literary training/indoctrination. It figures that the example given would be– what else?– an English class. Uh, is college over with yet?

There’s a difference between readers being assigned a book to read in order to pass a course, and the stray person browsing at a bookstore who takes the “Oblivion” collection down from a shelf for a moment to peruse it. There’s little structure– artistic form– to “Mr. Squishy.” Like so much else DFW writes it’s a mass of description. Obsessive. Too much.

The point is always vague– like in the recent Harper’s DFW story about a new employee, whose extended scene is the employee standing outside with his co-workers on a break. What’s it about? Hell if I know! Wallace captures every nuamce of the situation, but what’s he’s really capturing is the boredom of life. Or, his apparent boredom with it. It’s like an Andy Warhol movie. A nice experiment, but does nothing to expand the importance of the art form. Wallace uses more words than other writers, but he does so in order, usually, to narrow the focus. His swimmer standing on a diving board, hyperaware of the situation. Ultimately, this is the awareness of the self, the consciousness, as aware as a watching house cat but learning next-to-nothing about the civilization he’s part of. When his digressions do seem to address the civilization, you’ll find instead they’re about the media noise of our civilization. Postmodernists, as is implied in another post here, address the world through layers of theories and courses and classes, but also through the barrier of media– in DFW’s case the enormous amount of TV he ingested in his life. Not quite the direct experience of a Jack London! (Insert snarky remark here.)

It’s unfortunate that Wallace never read anything by Jerry Mander. . . .

Young writers are insane for following the Wallace-style of fiction. It’s literature rooted in corners of the over-stimulated intellect, the overwhelmed brain, when the true concern of the writer should be in the heart and the soul. Those are the chords to play which are most important.

I have a post up at my main blog comparing DFW’s style of writing and thought with gnosticism, for what it’s worth. I’m not here to advertise. Anyone interested can search for it.

Did you even go to collage, Wenclas?

Or college, either?

I’ve got to say, for someone who seems to be attempting it at great length, you really suck at communicating.

I agree with several of your points, and I read through your posts very carefully, as a result, to give them their full credence. This site is very academic, for instance. From what I understand it’s run and populated mostly by MFA graduates or soon-to-be’s, some teachers here and there, I think, and in general since that is the type of person which comprises the indie lit world, and this happens to be an indie lit site, I’m not terribly shocked by this, nor do I find it something terribly worth commenting on.

You make many other points I could see reality or truth in, but too often I wonder either why they are points which need to be made now, or why they are points which need to be made in this way.

Less polemic.

Jake, Jake Barnes, I believe.

I was merely trying to provide a little evidence to back up my claim. If you want a more popular and less academic example, there’s the whole Infinite Summer thing; I doubt a writer whose work is unreadable as you claim could carry such a successful bookclub-thing.

Either way, you still haven’t provided any evidence for why “most people” can’t make it through the first page of DFW’s stuff, which is what I’m mainly interested in.

As to the rest of your post: I appreciate the well-thought-out reply, but I’m not very sure how to reply to it, or even if it really concerns me. Like many critics, you seem to judge Wallace’s work (and literature in general) according to a certain set of moral principles. As a reader I am not that sophisticated; I merely read what I like, which is a large enough task for me. Even if what you say is true, I ultimately would not be very concerned about a coming wave of “literature rooted in corners of the over-stimulated intellect.” As a reader I don’t really care how the stuff I read gets done, or where it comes from. Heart, intellect, soul, toe, asshole–whatever. If I like it I’ll read it.

And for what it’s worth, I don’t think DFW’s intellect was particularly overstimulated. He was a curious guy, and he read a lot, but as I re-read his stuff the so-called “intellectual fireworks” interest me less and less. His critical essays are downright disappointing, IMO. I’ve always been most enamored with the humor and pathos of his work, and while I think the pathos holds up well, lately I find that I groan and roll my eyes at his jokes more than I laugh at them. Anyway, gnosticism is something I’ve been wondering about a lot lately, so I’ll probably check out your essay. Cheers.

Gold star, NLY!

I was merely trying to provide a little evidence to back up my claim. If you want a more popular and less academic example, there’s the whole Infinite Summer thing; I doubt a writer whose work is unreadable as you claim could carry such a successful bookclub-thing.

Either way, you still haven’t provided any evidence for why “most people” can’t make it through the first page of DFW’s stuff, which is what I’m mainly interested in.

As to the rest of your post: I appreciate the well-thought-out reply, but I’m not very sure how to reply to it, or even if it really concerns me. Like many critics, you seem to judge Wallace’s work (and literature in general) according to a certain set of moral principles. As a reader I am not that sophisticated; I merely read what I like, which is a large enough task for me. Even if what you say is true, I ultimately would not be very concerned about a coming wave of “literature rooted in corners of the over-stimulated intellect.” As a reader I don’t really care how the stuff I read gets done, or where it comes from. Heart, intellect, soul, toe, asshole–whatever. If I like it I’ll read it.

And for what it’s worth, I don’t think DFW’s intellect was particularly overstimulated. He was a curious guy, and he read a lot, but as I re-read his stuff the so-called “intellectual fireworks” interest me less and less. His critical essays are downright disappointing, IMO. I’ve always been most enamored with the humor and pathos of his work, and while I think the pathos holds up well, lately I find that I groan and roll my eyes at his jokes more than I laugh at them. Anyway, gnosticism is something I’ve been wondering about a lot lately, so I’ll probably check out your essay. Cheers.

Also, I don’t even have a bachelor’s degree, so, you know, maybe keep in mind that not all of those who disagree with you fit into that “hyperacademic dweeb” cartoon that you’ve constructed.

It’s not much of an essay. It’s just Wenclas saying that certain apocryphal Christian texts were unreadable and that’s why they are apocrypha and not canonical.

??? That you read opinions you disagree with as polemical is your problem, not mine. I’m stating an alternate point-of-view. A difference, not in morality, but philosophy.

*************

“Indie lit”? Really? But this site in part is funded by Harper Perennial. The guy who runs it, Blake, is published by HP, which last time I checked was part of a gigantic conglomerate. Which is fine, if that’s what your about.

I see the site as just another arm of the literary establishment.

IMHO, no one invests the time and money in getting that MFA certification if he/she truly wants to be different from the crowd. Independent. I might be wrong– or concede, and hope!, that MFAers can get over it.

My entire involvement with literature has been as an independent. I’ve sold zines and books everywhere; shows; stores; readings; festivals; street fairs, even in saloons and on streetcorners. Yes, I have ideas about what the general public is looking for, based on much direct interaction, face-to-face, with that public.

************************8

Blake’s own gnosticism is easy enough to show. “–infecting me with what I do not realize I am being infected by because it is in me and so becomes me.”

It’s a looking ever inward for answers, for knowledge, which was the foundation of gnosticism. There is truly nothing new under the sun, is there?

My point is that it’s an intellectual and artistic dead end. It leads in fact not to knowledge, or intelligence, but the reverse. (Which is why I called it pseudo-intelligence. I wasn’t being merely polemica.) The philosophy leads to: nothing. To Oblivion, which is clear from the words of Foster Wallace and Blake Butler both.

To quote Blake:

“–evoking something that otherwise does not exist” “a sum towards the zero”

“we’re talking about writing about writing about a thing that does not exist in anything but in traces.”

It’s a negative philosophy without question. The end point, again: Oblivion.

Sure, I believe that this philosophy, and the writing style which conveys it, isn’t the way to connect with a general readership. I present a counter philosophy. I’m seeking a counter aesthetic.

*************

Anyway,sorry for the intrusion, and thanks to Blake and Company for the space and the time. I present my ideas to people I know will disagree with them, in forums like this one, because it’s a way to clarify to myself those ideas. Just as I hope my remarks can help in some small way others to clarify to themselves their own thoughts.

Why do you say that the gnostic quest has no intellectual value at all? I can understand the limitations of mere introspection, but I think gnosticism amounts to more than that. But, “know thyself”–that’s a dead end?

And if gnostic searching is a dead end, can you suggest a philosophy that isn’t?–a positive alternative? I’m curious as to where you’re coming from in reacting so harshly to gnosticism. (Pure empiricism?)

The best blog posts make me go and pick up something to read. I’ve been holding off on Oblivion because I don’t want to run out of DFW. Just the promise of the link to this essay saved in a .docx file was enough for me to pick it up this morning and shoot through it on the train, at lunch, on the rails back home, in bed. Thanks Blake, for that.

‘It’ being ‘Mr. Squishy.’

and a post script thanks for coming to the end of the story, facing oblivion, and then having somewhere to go to find a hand in the void.

[…] This past week also found me delving into David Foster Wallace’s Oblivion and Gary Lutz’s Partial List of People to Bleach. In terms of the Wallace collection, I’d been curious to read it before opening up The Pale King, as I’d seen certain concerns from one reflected in reviews of the other. (Said unfinished novel is what I’m currently reading.) By and large, I’m utterly stunned by what I read — in some ways, I’m tempted to say that it’s my favorite of Wallace’s books, though it might be too premature to say that. What’s done in it with language, structure, plot, and pacing are masterful; it’s a book to savor, and to learn from. Right about now would probably be a good time to point you to Blake Butler’s essay on Wallace’s “Mister Squishy.” […]

so I guess M.C. did not successfully “knock him off his pedastal” for you

nice post

As a relative newcomer to DFW, and a total newcomer to this blog, I Googled* ‘Mr. Squishy’, having finished reading it this morning and craving some analysis. And while I was happy to come across this essay – and pleased that someone would spend their precious time penning a lengthily analysis of an excellent short story, rather than engaging in the myriad useless and bullshittish activities open to modern man – I’m afraid, Blake, that I found this essay to more or less exemplify the worst and most unappealing elements of what is broadly dubbed ‘postmodernism’.

It goes beyond the fact that it reads, from the first sentence, like an “obsessively hyper-analytical post by someone who apparently spent too much time in the academy,” (Karl Wenclas) – many people, myself included, up to a point, wouldn’t mind this. The trouble is that much of this reads like more or less deliberate obfuscation; like words actually intended to mask anything like a real transmission of ideas. Indeed, there are large stretches of it which I genuinely don’t believe anyone – perhaps even yourself – have anything like an understanding of. Many of the sentences read quite literally like (at best) jargon-led poetry, or (at worse) well-worded gibberish – “An amorphous unrevealed overorchestrated truth in the first place. Ruining the ruin”; “What is human about being human is that anything that is human is not human and to say such is the void of the void.” – which, by the very weight of their vocabulary and knotted syntax, force others, so desperate not to appear uncomprehending in the face of something so clearly positioning itself as ‘postmodern’, to reply “Rad essay, Blake,” but not try and actually engage in any sort of discussion – after all, how the f**k would they go about doing that, having just been told that “These prongs of the text, bending inward toward no full absolution, suggest for our hypothetical hero, of no hero, to become rendered to the void: separated even from the him of him, unto the ending, regardless of his ploy”?

I think this post is perhaps coming off as harsher than I intended. To stress, I think it’s wonderful that someone has gone to such lengths dissecting this story, and you are clearly an intelligent, passionate and deeply engaged reader and person. But the way your piece is presented (at points) expresses absolutely pitch-perfectly the layered, vaguely masturbatory and intricately vacuous convolutions of that total entropy of ideas and concepts so well-depicted by another postmodern writer I am sure you are familiar with.