I Like __ A Lot

I Like Caitlin Horrocks A Lot

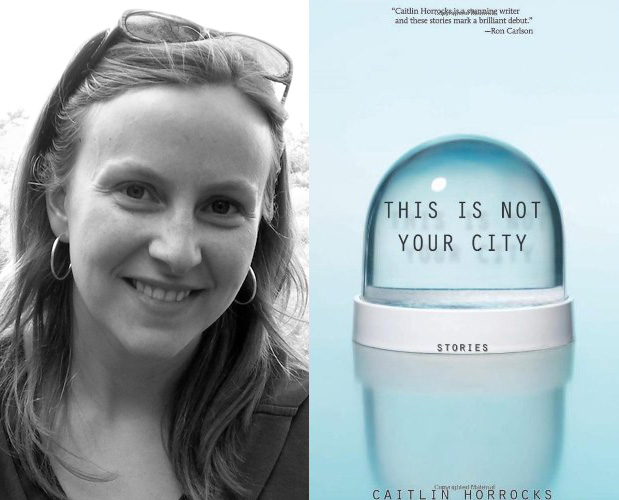

This Is Not Your City (Sarabande), the debut short story collection from Caitlin Horrocks, was released in July. The New York Times called the book “appealingly rugged-hearted” in its review and other critics have been equally favorable. Caitlin’s writing has appeared in Best American Short Stories 2011, Tin House, The Paris Review, One Story, Prairie Schooner, Blackbird, and many other fine magazines. She teaches at Grand Valley State University. I read Caitlin’s book several times this summer and what stood out about this collection was the diversity of voice, point of view, form, and style. No two stories were alike and the collection contains what may become my favorite short story of all time, “Embodied,” about a woman who has lived 127 lives. In my review, forthcoming elsewhere, I write about how Horrocks is not a writer you’d typically see named as an experimental writer. This collection, however, makes a strong case for her inclusion in that category because of the subtle but innovative experiments she tries with the eleven fine stories in a very strong collection. Over the course of a few weeks, we had a great conversation about writing toward emotion, what it means to be a Midwestern writer, and much more.

One of the things I noticed about the stories in This Is Not Your City is how varied the geographies where these stories take place are. Where are you from? Are you a traveler? How does place inform your writing?

I grew up in Ann Arbor, Michigan, and before I got to grad school virtually everything I’d ever written was set there. It was the only place I felt like I knew. But I found it a difficult place to write about. I’m still not entirely sure why. I suppose the books I knew seemed to feature lyrically described natural settings, or small towns with colorful, hardscrabble characters, or big cities. I wasn’t sure how to depict a mid-sized, liberal, quirky, college town, and the whole literary idea of the “Midwest” is underdeveloped compared to the American south or west. I dodged the whole question by deciding that part of a writer’s education should be learning how to write about other places, anyway. I went to college in rural central Ohio, and then lived in England, Finland, and Prague. I traveled a lot for a few years (and still do, as much as I can), and realized how important those experiences were to me personally, as well as what they could offer my writing. My story “The Lion Gate” started just because I’d been to Greece, and to the cistern in the final scene, and I wanted to write about it; almost everything else in the story came from wanting to get the characters down inside that place, and creating two people for whom that moment would be meaningful. I’ve had various stories start that way, and then I try to make sure that the setting isn’t just window dressing.

I agree that the literary idea of the Midwest is quite underdeveloped. Why do you think that is? Do you consider yourself a Midwestern writer?

I consider myself a Midwestern writer, but I say that out of pure geography. I grew up in a place that most people identify as the Midwest, and I live there now. That said, I’ve had people from Kansas wrinkle their noses at me and say they “suppose” Michigan counts as the Midwest, but it’s really more the Great Lakes. Or the Rust Belt.

It’s hard to pin down an idea of Midwestern literature when no one can even pin down what the Midwest is supposed to be or look like. Is it a Nebraska prairie; the Michigan lakeshore; Gary, Indiana? If there’s an image of the people who live here, it’s that we’re very polite and vaguely wholesome and dull. No region is monolithic, but the Midwest is often just a catch-all, the fly-over states that don’t belong to some other region. It’s hard to make a cohesive identity, or literature, out of that.

Do you write toward or from a place of emotion?

I love this question. Towards. My story beginnings tend to be a bit analytical, the desire to take on a structure or plot I’ve never tried. But if a story remains just an exercise or experiment, I’ve failed. Somewhere along the way the characters or situation become real for me, and I identify emotionally in a way I didn’t at the beginning.

It’s interesting that you begin your stories somewhat analytically, approaching stories as experiment. One of the things I noticed in This is Not Your City is the diversity of the narrative approaches. “It Looks Like This,” dug its nails into my heart immediately with the narrator and her humility and voice. I also loved the pictures she shared from her life. Was this story an experiment? Was the experiment successful?

It was definitely an experiment, and it came very directly from a “Forms of Fiction” class assignment, to write a choose-or-invent-your-own-form-story. I immediately thought of doing an illustrated story, but I had to think of some pretext—I wanted the pictures to feel essential, not just quirky or decorative (and I have virtually no drawing or design skills, so I was unlikely to pull off “decorative” anyway). I thought of a student including images to take up space, a reluctant writer who wanted to reach her page count more quickly, and that made her voice pretty easy to hear. Her life came from her voice, from this very matter-of-fact recounting of the things and people around her. I think the experiment was successful, but I really owe one to the editors at Blackbird, who suggested a final scene between Elsa and the narrator. In the draft I sent them, Elsa just sort of disappeared from the story, and the reader and narrator missed out on the touch of hopefulness that her final scene gives.

A lot of writers have a certain kind of story they tend to write over and over again. What is your story?

I hope I don’t have one, but everyone probably does. One of the great, strange pleasures of publishing a book has been reading the reviews and seeing what other people think are my themes or preoccupations. So far theories include cruelty, loneliness, love and guilt and being middle class, among others. I hope they’re all true, and that that means that there’s no single story I’m retelling.

Many of the women in your stories are displaced in some way–from home, from themselves, from their histories. Do you see this theme in your writing?

Yes. Several of the stories come very directly from my own feelings of displacement as I lived or traveled abroad–not necessarily specific autobiographical experiences, but the same feeling of distance, an awareness of being separate from the language or people around me. But there are only so many Confused American Abroad! stories anyone can stand to write or read, so those feelings of displacement hopefully take on other shapes and origins in the stories.

It’s hard for me to pick a favorite story in your collection but “Embodied” comes close because you wrote so believably about a woman who has lived 127 different lives. There was nothing implausible in how you told her story. How did you come up with this story?

I was doing a short exercise that asked for a “monologue,” and the reincarnation was there from the beginning. I was just entertained by it, this voice with these outlandish experiences. But as I kept writing, long past the page count for an exercise, just thinking aloud in this character’s voice, about what her experience would actually be like, the more miserable it got. She wasn’t wiser or spiritual than anyone else, she was worn down and burnt out, and her actions felt like a logical result of those 127 lives. “Embodied” is the oldest story in the book. I was 24 when I wrote it, and I was proud of trusting the writing process itself, just hanging on and typing pages about past lives until some kind of plot started to emerge.

When I got a copy of your book in my hands, I immediately turned to the Table of Contents to see if “Life Among the Terranauts” was included. How did you assemble This Is Not Your City and decide which stories to include?

“Terranauts” isn’t there purely because of timing. The book manuscript was under contract with Sarabande before I’d even started that story, and had already gone to copyediting and layout before I finished it. There was no conscious decision to leave it out.

A few stories were removed from the manuscript because my editor thought they were less strong than the others, and I didn’t disagree, or at least not strongly enough to lobby for keeping them in. “Embodied” is the only story she was unsure of, that I wanted to fight for, and it stayed. As you’ve already mentioned, there’s a wide range of settings and narrative approaches in the stories, so I was worried about the book seeming too disjointed. But that hasn’t really been a problem. My main attempts at cohesiveness were focusing on female main characters, and ordering the stories roughly by the age of the protagonists. Other than that, the book was assembled by choosing the best stories I’d written at the time and discarding any that seemed wildly out-of-voice with the others.

Which story is your favorite in This Is Not Your City?

I really can’t choose. That sounds like a dodge, but it’s true. It would feel like picking a favorite child.

Is your writing ever autobiographical?

Yes, but the true stuff is almost always some hacked up potato pieces in a much larger stew. The cancerous rat in “Zero Conditional” was real, the owl pellet project was something I did in 7th grade, the museum exhibit and planetarium show were both real, the fish tank snails came from something a friend once mentioned in passing; but nothing the main character actually does in the story is autobiographical. Well, I’ve shared her feeling of exasperation with a roomful of little kids, but my classroom never descended into a desperate reign of terror and dead animals.

I know you went through quite an ordeal getting your book to print. How do you feel now that your book is out in the world?

Happy. Relieved. It was a thrill to give my first reading from pages that someone who believed in the book had paid to have glued together, a picture printed on the front and my name on the spine. I had a solid, rectangular sense of satisfaction. And anxiety: now comes the hoping that people will read the book, that they’ll enjoy it. I get to hope that enough people will actually buy it for someday someone to let me publish another one.

Your work has appeared in magazines like Tin House and Paris Review. You’ve received a Pushcart and have been included in the O’Henry anthology. Many writers define success as achieving some of these milestones. How do you define success? Do you feel successful as a writer?

The pure, noble, writerly answer is that success comes from knowing I pulled a story off, that I’ve done right by it. And it does. But the more honest answer is that publication or recognition also feels like success, and helps me believe that I pulled off the writing. I’m still working on my internal compass, on knowing when a piece is done or how it compares to other work I’ve done. I lean on friends and readers, and external successes like publication or awards, to help me know those things. I probably shouldn’t. I’d like to say I don’t give a shit. But if winning something felt like failure, I’d be doing it wrong.

Calculating success only on the basis of awards or publications, though, is guaranteed to make a person crazy because there’s always going to be someone winning bigger awards, or publishing in bigger places, or making more money. Way more money. Or writing better work, and deserving all the accolades. It would be disingenuous to pretend that the milestones you mentioned don’t matter to me, but it’s more important to feel like I’m producing work that might deserve them.

As writers, rejection is a constant. How do you deal with rejection?

Not to fob this question off on someone else, but I thought Blake Butler’s HTMLGIANT post, about learning from submitting writing and being rejected, was fantastic. I’d add to Blake’s, “you should never feel shitty for a rejection,” that sure, go ahead and feel shitty. For about thirty seconds. However long it takes you to read the email or open the envelope and then enter the response in your submission log. Then you look at where else the piece is still at, and wait for something to work out. My most-rejected story is one that won several awards before being published, and then it won a Pushcart. The process is such a crapshoot.

When I was first sending work out, a personal rejection was seriously as exciting as an acceptance might be to me now– someone out there had read my work and liked it, whether or not there was room in that particular issue of that particular journal on that particular day. Since then, my ‘yes’s have come in pretty generous proportion to my ‘no’s: rejection is a constant, but I’ve never dealt with truly constant rejection. The idea of that still scares me, as does the prospect of that kind of rejection on an entire book. That may be part of my self-diagnosed novel writing phobia: it’s a lot of years of eggs to have in one publishing basket.

You have a novel writing phobia? Are you working on a novel?

Over the past few years I’ve worked on two. The current one is at least going better than the previous book, and the research for it is interesting. But I feel like a middle-distance runner trying to retrain for a marathon. Not that I’d know what that actually feels like. I run like a penguin. But I imagine it feels like having a lot of the relevant skills and experience, but still not being quite sure how I’m going to make it all that way.

What do you love most about your writing?

It feels way too narcissistic to answer this with love for the finished product, so I thought I’d answer with what I love about the process of writing. But then I realized my curmudgeonly answer is often “when it’s over.”

Writing isn’t torturous, and I’m much happier doing it than laying bricks or harvesting fruit or printing eviction notices (which I did, for an entire day, at a temp job after high school). But the actual act of putting words on the page isn’t that easy for me and it’s only sometimes fun. I love the days when it goes well, and I love when I finally wrestle a story to the ground and fix what’s wrong with it. But a lot of my writing love only happens in hindsight.

Picked this collection up this summer and really loved it. Usually I pick up a short story collection for inspiration for my own work as much for entertainment. This book was next to my computer all summer.

Enjoyed this. Great writer.

i read “I grew up in Ann Arbor, Michigan” and literly said “ann arbor aint shit” out loud

“My story beginnings tend to be a bit analytical, the desire to take on a structure or plot I’ve never tried. But if a story remains just an exercise or experiment, I’ve failed.”

Good answer, good question, good interview.

[…] Roxane Gay interviews Caitlin Horrocks at HTML Giant. […]

[…] not included in the collection). HTMLGIANT did a great interview with Horrocks, which you can find here. When asked if her writing is ever autobiographical, she says, “Yes, but the true stuff is […]