Opinion

My Contribution, by Shaun Gannon, age 27

Finally! After years of toiling in the disgusting machinery that is Alt Lit, I’ve become a contributor to HTMLGiant!

SO LET’S BURN IT DOWN.

And I am going to do so in the most fitting way that I could conceive.

I could first tell you how this webbed site gave me a chance to connect with some amazing people across the world at a time when I was otherwise surrounded by toxic people in a small, dying town — but I won’t, because I don’t feel like burdening the world with another story of an awkward white male using the Internet, as that is not fucking interesting at all.

I could also talk about how the filth that washed up on this site (meaning, the pieces of shit written by larger, animate pieces of shit) was surrounded by posts written by people who truly cared for one another, posts where they shared their feelings, concerns, and insight in the hopes of making a connection, but I don’t feel like defending a corpse. It’s not my job to champion some abstract thing’s legacy. I’d prefer to spend my time living.

At first, I thought I could talk about a number of individuals I’ve recently disassociated myself from, both professionally and socially, but I couldn’t, because of my rage.

I had forgotten the unique feeling that comes with this kind of rage — one that stems from having your core shaken; distrust seeps in and boils the blood. It’s a woozying sort of anger that I hadn’t felt since I was in middle school, when my father was revealed to have molested multiple children over several, if not dozens, of years — an anger that was compounded by the lenient treatment he received from society and the justice system because he had been a police officer. Looking at someone who is a criminal, or something worse, and knowing that justice will never come summons something inside me that I try hard not to look at for too long. As such, I felt if I wrote another sentence in that train of thought, I was going to explode. (To be fair, this is the first time I’ve shared any of this information in a public venue.)

So ultimately, I’ve decided that the best way I could honor-kill this site would be to write about something that means so much to me, in the way that HTMLGiant does, or did, or whichever tense you’re supposed to use with dead things, and so, I present to you my 2600-word essay on the Dynasty Warriors video game franchise.

While the Dynasty Warriors series is best known throughout the world for pitting players against dozens of computer-controlled enemies at once, Dynasty Warriors originally began as a one-on-one competitive fighting game, released in 1997 by Japanese game company Koei. In Japan, it was named Sangokumusou, or “Three Kingdoms Unrivaled.” The game’s badass name was derived from the source material of the series — Romance of the Three Kingdoms, a Chinese historical novel commonly attributed to Luo Guanzhong. RoTK is a recollection of the war following the fall of the Han dynasty, from ~169 to 280 AD. I won’t spend too much time discussing the book, because why would I do something like that on this website? Instead, here is a brief overview of the storyline, followed by the minute differences between the games in the series.

Plot

Shinsangoku Musou, or Dynasty Warriors 2, established not only the standard hack-n-slash gameplay of the series, but the usual series of stages to appear in each game as well. The games open with the uprising of the Yellow Turbans, who are essentially painted as a terrorist faction relying on magic to be pains in the ass to the nice folks who just wish to conquer the entire nation by force. (Some titles in the series feature a storyline where you play as Zhang Jiao, leader of the Yellow Turbans, and his constant babbling about the Way of Peace doesn’t help his image much.) This leads all of the major players in the game to unite, before most of their kingdoms were even possible, let alone established.

These same players appear in the following stage (or series of stages, depending on the title involved) in an alliance to stop Dong Zhuo, the corrupt city official who seized power while all the generals were out playing War in the sticks with the magic guy. The sieges of Si Shui and Hu Lao gates leads to the reveal of Lu Bu, the official’s bodyguard and a recurring villain whose character is basically just “the strongest bully,” and eventually to the defeat of Dong Zhuo, who scampers off to get killed in a much more nefarious plot befitting a corrupt leader in government. At this point, whoever the player chose in the beginning heads back home, and the storyline splits into those of the rising empires.

Wei, Wu, and Shu: the three kingdoms that grew from the chaos of the Yellow Turban uprising, each led by a very different group with their own distinct storylines in the game. Shu is led by Liu Bei, painted as a virtuous man who slowly builds a ragtag team of the best damn fighters you ever done saw north of the Yangtze. Cao Cao is the power-hungry Wei general who is made to appear not as the bad guy, but he definitely surrounds himself with the largest group of humorless dicks. The Wu Empire is led by the powerful Sun family, ancestors of the great Sun Tzu and are set up so that the only person in the family who doesn’t get killed off right away is the sole daughter, who is instead married to Liu Bei, which leads to some great soap opera moments later in the games.

Some factions unite for brief periods, for reasons varying from pledges of fealty (such as Shu’s Guan Yu serving under Wei’s leader Cao Cao during the Battle of Guan Du) to sheer desperation (such as Shu and Wu uniting to battle the Wei naval fleet at Chi Bi). Such alliances were always brief, usually ending due to sudden imbalances in power and with some such general fleeing for his life from a castle. After alternating between squabbling with one another and taking a few trips south into the jungle to fight/recruit the Nanman tribes, the three kingdoms eventually become two, and finally one.

But which kingdoms, you say? Well, that depends on the entry you play. Earlier titles, like Dynasty Warriors 2, 3, and 4 simply had the side that you chose become the ruling empire, with different endings for each faction. The middle games in the series opt for endings that are more accurate to the source material, where the timelines for each faction simply end at different points. Wei lasts the longest of the three, as Cao Cao is succeeded by his spoiled, even grumpier son, Cao Pi, but the final rounds of battles are usually around the same time period.

The most recent entries in the series have expanded beyond the initial deaths of the three kingdoms and are the most accurate entries to date. This is due to the inclusion of a fourth faction, representing the Jin dynasty. After the death of Cao Cao, his tactician Sima Yi seized the emperor’s throne and took power over all that had once been Wei. At this point, Wu was basically a non-entity since the death of the last surviving member of the Sun family, so the Jin army fought against Shu, led by Liu Bei’s weak son Liu Shan. Dynasty Warriors 7 was the first to include this faction, and as such, has only a handful of levels. It was not until Dynasty Warriors 8, the most recent entry of the series, where the Jin faction would receive a fully-fleshed out storyline.

This was possible due to the second major change in story mechanics; when nearing the final act of the game, the player is given an option to enter a storyline that more accurately reflects historical events, or to finish with a storyline of conquest more similar to the endings of the earlier DW entries. These are only available upon meeting certain battle requirements in the game – basically, performing actions that fly in the face of historical events as they unfold in the levels (saving a doomed character’s life by flying over there before they get iced, etc.) – and so will require multiple play-throughs before they are available. Rushing into a battle requires more skill and stats than a level 1 character can survive. Which leads to the next section of excruciating detail!

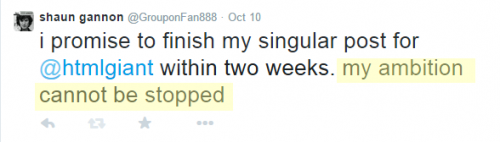

“Foreshadowing Tweet.” @GrouponFan888, 10 October 2014. Category: DYNASTY WARRIORS QUOTE. Additional Info: This sentence is basically my personal hanging cat poster (the motivational kind, not the fucked-up kind).

Gameplay

Describing the differences between Dynasty Warriors and DW2 would take forever, as they are different genres, so to prevent this essay from ballooning into 8,000 words, I will pretend you know what fighting games and hack-n-slash games are – okay, I will pretend that you are reading this, and also that you know what those are – and simply say that DW1 is not great because it’s a really slow fighting game, and while DW2 is also slow by today’s standards, at least it doesn’t feel as frustrating, probably because this is when they begin to allow you to ride horses.

Dynasty Warriors 2 began the hack-n-slash series in a very basic manner, as you have a ring of characters you can choose from with three stats – Life, Attack, and Defense – and these stats level up as you complete stages or defeat certain high-ranking officers, and that’s it in terms of character progression. I will not list the characters or their backstories in this essay because the latest game is up to (I believe) 120 available characters or so, but just know that they add more and more characters to each subsequent release.

As the series progressed, the character advancement became more detailed and interactive. For example, Dynasty Warriors 6 included a skill tree where characters can gain additional moves, abilities, resistances, or stat boosts. However, this skill tree is capable of being maxed out quite easily, so while you may not end up having a great deal of influence on the character’s attributes, at least it provides some more differences between the fighting styles.

And there are already quite a great deal of differences in fighting styles, as each character has a unique weapon and moveset that can sometimes change from entry to entry. For example, most characters use spears, swords, and halberds in the earlier entries, others use weapons such as crossbows, staffs, bombs and other perfectly reasonable objects like floating knives, cannons, and a lance split into sections that spins like a giant drill. Sometimes, characters well known for using a certain weapon will arbitrarily switch for something else for an entry. DW6 is the most egregious example, as a lot of characters were given a generic spear and the same moveset, while others swapped weapons, and some were simply cut. The one good change in DW6 regarding weapons was with Sima Yi, who normally uses a big dumb feather fan and some lame magic, but here he wields these crazy… fingertip razorwire… contraptions… look, I don’t know how this stuff works, all I know is that it looks badass, alright? These are games about looking badass while killing hundreds of soldiers. But with a lot more history than most other games.

One of the biggest gameplay changes from DW2 to 3, besides adding two-player co-operative play, was a second leveling system added to the weapons themselves. Similar to the character leveling, each character’s weapon has a simple experience bar that fills only with the defeat of enemies. This “bathing in blood to grow in power” game mechanic (okay, I totally read that into the game, but whatever) is a reasonable method of game progression, but later titles provided more opportunities for customization and strategizing by having officers drop weapons upon defeat. Most entries with weapon drops only have you pick up weapons that the current character could equip, but some entries include randomized roster-wide drops, which means you could find 9 weapons for 8 different characters, none of which are who you want them for. (I could be mistaking this last part for one of the Warriors Orochi spin-off games, as I am writing the vast majority of this from memory.)

The fighting system that has been the core of Dynasty Warriors since the initial sequel – the standard, charged, or special (also known as Musou) attacks that can be combined in various sequential orders depending on the necessary tactics – has not changed much over the years. An additional Musou attack is available in later versions when a Rage token is picked up, as this allows the player to enter a sort of “hyper mode” that slows enemies, speeds the player, and grants additional bonuses that ends with a devastating finishing blow that kills most of anything around the player.

Perhaps the most interesting and enriching gameplay change appeared in Dynasty Warriors 8, which implemented a sort of “rock-paper-scissors” element while combatting more difficult opponents. Unique enemy officers and other high-ranking opponents each have an element attributed to their weapon, which is visible next to their health bar. By using a weapon with a different element than theirs, the player is either at an advantage or disadvantage in combat, which affects the power of attacks. Because Dynasty Warriors 8 also allows the player to now equip two swappable weapons before entering battle, additional strategy becomes necessary, especially at higher levels, before and during the battle.

While each stage features either a final enemy commander to defeat or an endpoint to reach (primarily in levels where the goal is to escape rather than fight), the series recently implemented side missions that can provide benefits on the battlefield upon success, such as capturing bases to release additional allies. These missions also reward the player with an experience boost after successfully completing the stage.

Such missions are often a requirement to unlock some of the more advanced weapons and items in the game, as they are often challenging tasks that must be accomplished within a strict time limit. The top-tier weapons are earned this way, rather than by simply maxing out their levels, as well as the fastest and most interesting mounts, like the elephant and the legendary warhorse Red Hare, which they have slowly made more demonic-looking with each new entry in the series. In DW8, he is about eight feet tall and has burning cinders flying off of him.

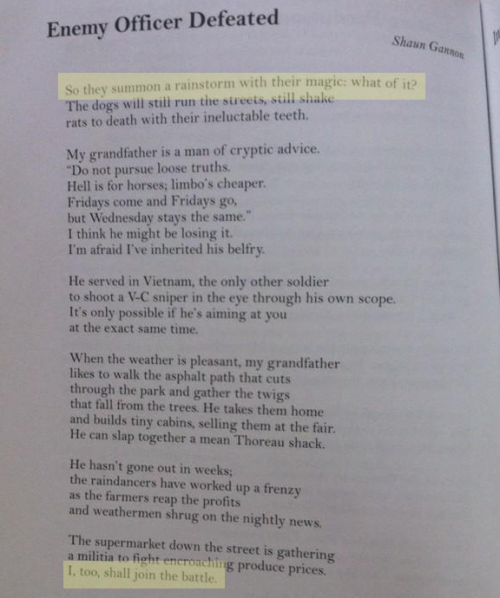

“Enemy Officer Defeated.” Broken Plate, Spring 2010. Category: DYNASTY WARRIORS QUOTE. Additional Info: Title is a bonus quote; photo by Layne Ransom.

Graphics

This series did not always look so sweet, though. Since Dynasty Warriors was first a 3D fighter for the Playstation One, the less we speak of its graphics, the better. DW2 was not much better visually, but it does feature cutscenes and a few FMVs (full motion videos – fully animated scenes, compared to character models running on the game engine, like in cutscenes) due to being the first entry for the Playstation 2, but it still lacked much graphical difference between characters, and the landscapes were eerily desolate.

Such wide expanses of nothing have slowly developed into more detailed landscapes with unique features that provide a sense of place, but because the locations of the battles mostly remain the same, this leads to a number of interpretations of locations such as Bai Di and the Stone Sentinel Maze constructed by Shu strategist Zhuge Liang. Sometimes appearing as a large maze through stony ruins, and other times as big pillars that shoot from the ground to block paths, such details are what the dedicated Dynasty Warriors fan looks for when playing the newest iteration of the series.

Each new entry also brings a whole new level of over-the-top ridiculousness to the action. In the Dynasty Warriors 8 intro FMV, a man mounts a barrel-rolling horse midair after an explosion blows up about 20 boats. While magic has always been present in the games, as it also appears in RoTK (which is a romance, not a historical record, which means a wizard can turn into a crane and fly away and no one will question it), the addition of ancient Chinese deities, fire-breathing statues, and those ridiculous floating daggers has made the series more fantastical and visually impressive with each release.

Most non-primary characters have grown more outlandish in each new game as well: For example, the Wei general Zhang He, long portrayed in the series as a flamboyant and graceful lover of death and destruction, eventually straight-up gained butterfly wings to his costume (and is clearly the best character in the entire series). The last two entries of the series have also added a number of fictional characters that are mostly pretty young males to balance out the additional women in the game – some of which are, yes, less dressed than a person should be on a battlefield, but the series seems to improve on this aspect with each entry, and there are plenty of powerful and appropriately-armored female characters as well.

Not everything in the series is arbitrarily cranked up to 11, though. Other characters were instead updated to more accurately reflect the people they represent from the text; for example, Wu patriarch Sun Jian has much greyer hair in recent entries to distinguish him from the rest of his family, who will continue on without him pretty quickly into the games’ storyline. The pirate turned general Gan Ning received cute lil’ jingly bells for his sash because he would wear them into battle, because sleigh bells were apparently scary back then?

While the gameplay has been pretty consistent since Dynasty Warriors 4, the graphical updates made in each version have been substantial enough that DW7 would be a much more enjoyable experience than DW4, especially on a big-ass TV. That’s mostly because DW7 is the one with the best ending FMV in the series: the rivals of the three kingdoms square off against each other in this big fiery torrent that swirls around them as they declare their loyalty to whatever cause they champion before battling to the death, and this combination of clashing ambitions, wide-encompassing political intrigue, and a claw-wielding butterfly man is why Dynasty Warriors is the best videogame series of all time, thank you very much. Gene, I told you I was going to do this — you’re welcome. Blake, you’re dead to me

u shld do a snippet too

i hope this gets a lot of comments

Very fine Heraclitan response to Cratylus, who criticized Heraclitus for saying that one cannot enter the same river twice, for he himself held that it cannot be done even once. I don’t know shit from Shinola about gaming, but I think I like your grandfather.

I made those parts up, as the grandfather in the poem is actually fictional; his advice mimics the language of the rogue wizard Zuo Ci, who traveled across the kingdoms in search of a man who was fit to rule. After trolling Cao Cao for a number of years, he decides no one is fit, turns into a giant crane, and flies away from Earth forever. My real grandpa is pretty much that awesome, though. Also, the first piece of advice is a sort of wordplay based on an infamous command from the series: “Do not pursue Lu Bu,” who would stomp you into the dirt if you tried to fight him at his first appearance at Hu Lao Gate.

Well, hell… Zuo Ci should’ve stuck around. Eventually, he would’ve come across this poem, and taken to heart something like your fictive grandfather’s lines about sturdiness among flux.

By running always in front of Lu Bu, you would ‘defeat’ him through the magick of paradox. Probably harder to do than to say.

I like the DW/SW series. Haven’t played the last five-years’-or-so worth.

Did you ever play this: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bladestorm:_The_Hundred_Years'_War

?

I saw one copy one time and regretted not buying it.

Before comments close, I’d like to ask how come you know so many poems? Do you memorize them and tell people about them? Do you just search a massive index of poems’ themes when searching for something to which to link?

—–

Lu Bu’s ‘objet fixe’ doesn’t react to paradox. Lu Bu’s programming preempts the fact that “paradox” is a result of “appearances” (a perception of perceptions) and fulfills its ruthless function without regard.

I have not! I usually prefer games where I can solo rather than command units, but the combat system with the units seems interesting, and I would definitely enjoy the story. Thanks for the recommendation!

DW8 is now cheap enough that I think it’s worth the cost, even if you only play through 2-3 of the story modes. They’ve included an Ambition Mode (I could have spent another 1000 words on it in the essay but decided instead to not go insane) so that you have a little base you develop through grinding in a series of randomized levels. If you view it as a Free Mode set at random where you can earn extra little baubles for your base, it’s alright, but it takes so long to build everything up that only the most hardcore players would really get everything out of that mode to completion – and that’s not me, because I have multiple jobs

I have a defective memory for poems verbatim, but I can remember that So-and-so wrote a thing, What’s-it. (Often, looking up a poem that I ‘remember’, I find a different thing. The reader ‘remembers’ constructively, the reader just gets it wrong, and so on. Similarly with movies: that most important passage in the movie, you see it again and that part is, say, forty seconds long, where that 20-minute sequence, you forgot completely right ’til it came up in your next viewing.)

The Tang poets – and I don’t know a word of the language, and the poetic conventions, only dimly at third hand – are probably worth getting into on a relaxed, long-term basis. Wang Wei (also an important painter), Li Bai, Du Fu, and Bai Juyi (whom I still think of as Po Chü-i) are the names, anyway, that I remember.

———

The command is ‘not to pursue’ Lu Bu. But if you went where he goes just ahead of him, he wouldn’t stomp you for ‘pursuing’ him, though you would have gained the proximity anticipatorily. It’s a “paradox”, a ‘simultaneous co-existence of contraries’.

It’s been a while, but I don’t think it’s possible to get there before him, in which case no matter how you approach him, he would be the target of your pursuit. Even if you could beat him to the gate, you would be ‘pursuing’ him by intending to meet and confront him as you would have that expectation.

It is possible to stumble upon his trounce-fest by accident, by ignoring or forgetting his position on the mini-map, but there would be no paradox involved.

#failuretocommunicate You’re not trying to reach Lu Bu’s destination before he does, and you’re unambiguously avoiding a meeting, much more a confrontation, with him. You’re anticipating his short-term direction and velocity (not his destination) in order constantly to stay in front of him; when he stops – say, at a gate – , you stop and wait for his next forward ‘step’ without facing him in a way mistakable for confrontation of any kind.

In this way, you’re not “pursuing” Lu Bu, but nevertheless, you’re ‘following’ the lead of his (anticipated) direction and velocity: paradoxically, you are pursuing him, but by always ‘leading’ him.

Of course, this kind of stratagem might be disallowed by the rules of a game or ‘world’ — about which, as I say, I don’t know anything. And if you do want to fight and kill him in that game or ‘world’, anticipating from ahead of him his next step would have to be folded into some martial plan of attack/defense (?) that might not work against his badass self anyway.

I think you’re positing an impossible scenario. He’s at the gate no matter what you do. (Or he doesn’t actually ‘exist’ in-game until you ‘find’ him by coming within [in-game distance] of the gate?)

Perhaps this is the paradox you seek: that another actor in the world could be both an incontestable individual force and also a mere piece of scenery. (Electric sheep, etc.) And the player’s will is forever subject to the infernal machinery of the game’s design. Yet the game’s design is but another’s will, whose will is for you to contend with it. (Video games made it new, brah.)

What Lu Bu is doing depends on the entry – in DW2, he’s first just milling about the choke point and can be led pretty far away from where you are by the CPU, which allows the player to sneak by, but can also end up just sticking around the gate. If memory serves me correctly, there are a number of entries where the phrase is used inaccurately, like in DW7 or 8 where he’s actually pursuing YOU and you have to just go beat Dong Zhuo before Lu Bu finds you.

I think at some point, the command just became part of the legacy, like a lot of the language/quotes from the individual playable characters. While large-scale events/titles/relationships are pretty accurate to the book, the game is not SO close to the source material that they directly quote people. So, there’s got to be some sort of continuity that’s not just from the books (the soundtrack is definitely one of those things, but it’s usually bland and easily ignorable and it got to the point where I was listening to a lot of podcasts while playing these kinds of games instead of the in-game soundtracks).

No, that’s not the paradox I’ve limned. But it’s an excellent one: scenery that’s agency, pathetic fallacies come to life. (If it’s really just a piece of scenery, then it wouldn’t be intelligible: if it were purely passive, the player/reader/irl-person would have no way of knowing it was there. pace Chekhov, if there’s a gun on a table in the first act, it doesn’t even have to be fired — there’s a gun acting – causing – in the characters’ and playgoers’ minds ’til the curtain comes down.) As you say, something for gaming to reinvent.

Yeah, it’s been a long time. I’m not sure which installment I’m remembering. Probably 2 or 3.

Using two senses of a word does not create a paradox.

…

Or does it?