Random

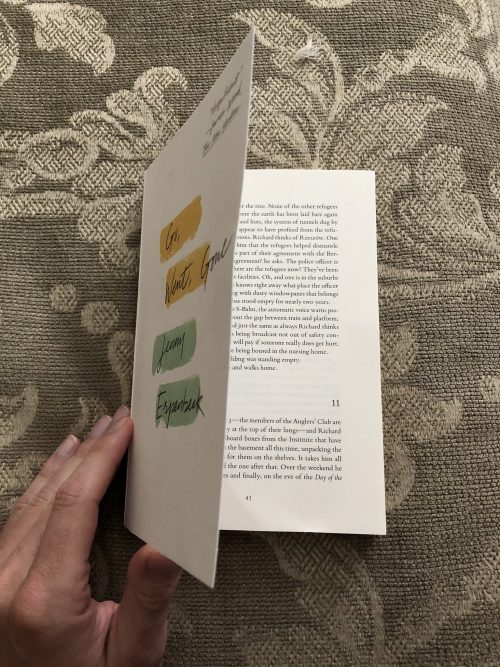

Go, Went, Gone without its beginning

My copy of the latest novel by Jenny Erpenbeck—Go, Went, Gone—began immediately on page 41, leaving out the first 40 pages and legal copy, which at first I thought was a intentional feature of the narrative’s design. I’d already read several pages in the mindset of having been dropped Finnegans Wake-like into midsentence and midaction until I realized it was just a misprint, and still I liked the feeling caused by a novel kicking off with: “any interest in the woman or the tree,” which then led directly into the next and first full sentence: “None of the refugees is anywhere to be seen.”

It took me a while to find a site I could read the first 40 pages on for free and on the spot. When I did, I found the missing section seemed immensely different than the part I’d already read—and, really, even after having finished the novel, all the rest of it to come. The missing section somehow also seemed connected to my recent reality in an odd way—the protagonist is a classics professor whose wife has died, in the ongoing absence of which he’s forever in the midst of figuring out how to live his life alone, removed from all he ever knew. Without those 40 pages, the story otherwise felt quite differently marked—concerning a man without much background, who takes an interest in a group of refugees being held in stasis by the German government.

I think I enjoyed the language of the book and how it formed. It felt bizarre to think this copy was unlike any other copy of the novel, and that I owned it, that I might be the only person to have read it in the way that I had read, which is true of all reading, I think, but this time in a way that jarred my brain. I thought about returning it to the publisher for a correct copy, already read, but I also found that I enjoyed the ghostly presence of the absence of its context. I enjoyed imagining the other ways the text could have been changed, not by the author but by the machines that gave it shape long after the author had moved on; the many other ways the nature of the story would be changed depending on other kinds of error never seen, overriding the possible pleasure of the intended plot with a looming sense that nothing is sacred, and anything might yet be done. This would haunt me throughout the rest of the novel, like I’d been given a glimpse of some expanse behind a curtain and then instead forced to move into a labyrinth around the novel’s fleeting, hidden heart. I kept thinking of the intent of the author as different than the intent of the book object, and the world the object existed within; that is, mine. It might break down at any second, I kept thinking; I might turn the page and find something there no other reader could have found.

Are there are other copies of this or any novel out there that start on different pages? Are there pages missing from books I’d already decided that I loved? How many different ways could the story learn to go based on the aspects of its impression in my attention? What happens when we lose a book we seem to love but haven’t finished reading? What else about it might be altered? What is ruin? Ultimately, the book itself might just be another kind of mask, subject to the whims of forces it can do nothing to withstand. Like a house falls in and underneath it is a landscape that doesn’t fit the rest of the landscape the house had previously existed in. Go, Went, Gone.

In default, this effect has been adapted by the industry to force most authors to believe their lack of control means they need to bend—I mean to kowtow to some median concept experience from the get-go, with the intent of catching as many readers as they can—the fragmentary and the ephemeral be damned. It espouses a future of literature as infected by the same ills that affect other forms of mass media unless attended to with firmer purpose, leaning in to the morphic haze that surrounds a reading experience and allowing that volatility in the shape of the work in a way that expands it, rather than falling in to a reality’s disease. About ten years ago now, for instance, someone wrote a manifesto titled Reality Hunger that in my view effectually suggested we all just do what we are told; that we are not alone because the act of art itself is definition a collage, meant for reaction, not a soul’s purpose.

I realize I am talking mostly to myself any time I read or write anything, despite the fact that anyone else on earth could go and pick up a copy of the same book, and anyone can type anything into a document filled otherwise with endless white, much like the terrain of the broken mind, infected and infecting. A friend I am in the room with reading the book near looks up and asks what it would sound like if all the songs ever written were played back at the same time, and I think about what it might be like to read all the books one hasn’t read yet printed on top of another as one draft; how that page, in contrast, would be almost entirely black, with tiny specks of blank spread like a dense Rorschach through which one’s preternatural imagination bleeds through. What is that backdrop? How might imagining it lead one forward into the realm of a new text?

It seems not fair for me to end here, having spanked my ass out loud about a book while only having typed about what the book is not. More than the plot or how it played out, I more enjoyed Erpenbeck’s logic and how her paragraphs amalgamate a flow, allowing ideas to fill in around its subject in a way that reminds me obliquely of Sebald, maybe sometimes Lydia Davis. I enjoyed the way she characterized the refugees by telling their stories individually through the lens of the protagonist as he appears to be finding new purpose in his life by distancing himself from his desires and instead trying to learn how to see other humans—humans in peril—for who they are. But despite the narrative devices clearly meant to depict the refugees interrupted lives, there remained for me a strong elusiveness to feeling I knew anything about them besides their pain, their resilience in the midst of being forced to exist in flux, between states. His befriending of the refugees and offering them an ear, a meal, a moment to play the piano, gives him space to let his own pain become a backdrop, the product of routine rather than purpose—but it does not stop the process of the machine in which all of their lives have been commingled only briefly, soon losing the connection to any other person as in a choppy sea high as one’s head, blueblack and silver; that though we may not be able to underline what has changed us, what waits to change us, you only have so long till it moves on.

“There’s my life, why not, it is one, if you like, if you must, I don’t say no, this evening. There has to be one, it seems, once there is speech, no need of a story, a story is not compulsory, just a life, that’s the mistake I made, one of the mistakes, to have wanted a story for myself, whereas life alone is enough.”

“but it does not stop the process of the machine in which all of their lives have been commingled only briefly, soon losing the connection to any other person as in a choppy sea high as one’s head, blueblack and silver” is a great line. Damn.

I think often about how and why I do what I do, other than just bald habit and inclination, or compulsion. And the book has always for me contained a presence that makes everything else seem not only tolerable, but alive and fascinating. So thinking what a book can be when it’s not what its makers intended is a fun way to renew that presence—and in any set of pages. This move makes me think of what can happen, too, when a person tries to shake off their biases and prejudices; since most books can contain many possible surprises, a reader no longer would have to only seek out a certain “kind” of book that fits their class/taste/predilections.

Reading this made me feel like books are sources of the impossible, again. A good gift, this feeling. Thank you.

what a trippy experience, and beautifully put. gonna check this one out

had a similar experience torrenting safdie bros’ ‘daddy long legs’ and watching the entire movie with vietnam sounds attached to it. was months later that i learned that wasn’t the original intent, but it is still unclear whether the safdies were behind the edit https://twitter.com/JOSH_BENNY/status/1258428265439559695?s=20

my copy of gary lutz’s complete stories has a bunch of pages in the middle that are upside down. i thought, when i first bought it, that maybe it was supposed to be this way. i later found out that it wasn’t, though i’m happy i own this pervert copy