Random

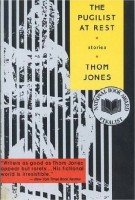

I Like It When Thom Jones’s First Person Narrators Break Into Essay in the Middle of a Short Story

Thirteen pages into “The Pugilist at Rest,” which is a twenty-three page story, which has up till now told a Vietnam War story, the first person narrator goes to white space, then returns with this:

Thirteen pages into “The Pugilist at Rest,” which is a twenty-three page story, which has up till now told a Vietnam War story, the first person narrator goes to white space, then returns with this:

“Theogenes was the greatest of gladiators. He was a boxer who served under the patronage of a cruel nobleman, a prince who took great delight in bloody spectacles. Although this was several hundred years before the times of those most enlightened of men Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, and well after the Minoans of Crete, it still remains a high point in the history of Western civilization and culture. It was the approximate time of Homer, the greatest poet who ever lived. Then, as now, violence, suffering, and the cheapness of life were the rule.”

A long essayistic passage follows, and although at first it seems like a digression, it actually serves as an introduction to the reflective thought about the events from the story’s first half which will inform the way the speaker reckons with the life he has after the war, which is always colored by the things that happened during the war.

In any given first person point of view, the narrative theoretically has access to the entire range of the speaker’s consciousness, experience, knowledge, intelligence, curiosity, and powers of reasoning and association. Sometimes when I’m reading Thom Jones, I feel jarred when these things intrude. I think this is because one way or another I have been conditioned by twenty or thirty years of American short stories that predominantly don’t make use of these resources, even though they’re available. Perhaps this is a function of the writers’ ideas about narrative compression in the short form, or perhaps it is an inheritance of the “no ideas but in things” school, or perhaps it is simply a manifestation of good old-fashioned American anti-intellectualism. But — God bless you, Thom Jones — I’m happy to be reminded of what I can do if I choose to do it. Even psychological realism is more bound by perceived limitations than by reasonable ones. We can do more if we choose to do more.

Tags: psychological realism, pugilist at rest, Thom Jones

Every time I think of Schopenhauer I think of this book. Great collection! (If repetitive)

This is a really interesting device for a fiction writer to use… and especially with the revitalization (real or imagined, as in, maybe it didn’t need revitalizing) of the essay, it seems like something that might have some legs as a technique. I think Cesar Aira does something like this in his novel Ghosts, dropping a 20-page tangential essay on architecture right into the middle of the book, but I haven’t read it, just a review at the Quarterly Conversation (I have read How I Became a Nun, which is trippy as all hell, but worth it—would fit well into the fever books discussion, actually).

My favorite parts of Moby-Dick are the nonfiction passages others complain about.

The famous story is this Jones stoy came out of the slush pile at the NYer, the first in about 15 years. Jones went to Iowa and just about everyone in his class was already famous. He was working as a janitor and having another go at writing for the third or fourth time. He didn’t resent the day job because it was one he could do where he could sneak away and read. I can never separate this aspect of the bio from the work.

I echo your enthusiasm for this story, Kyle, and the move Jones makes toward the essayish. He hurls us off-balance from the first sentence with “Hey Baby got caught,” which I think I had to read about eight times the first time around. I’d say the boldness of the story is not only in the move to the philosophical, the contemplative, but the sheer sharpness of the swerve from his voice and brute physicality, the way he once answered moral questions with blunt force, the way he wells up at the cliche-ridden Knute Rockne-like speech of his drill sergeant and abides by credos like “Jorgeson was my buddy, and I wasn’t going to stand still and let someone fuck him over.” Then all of a sudden he’s read a book or ten. The whole story is grappling with the relation between the physical and the nonphysical, call it the intellectual or the arguably-spiritual or whatever. Gary Amdahl does some similar things in Visigoth. All the Dostoevski references in “Pugilist” serve to remind me that for all of his Christianity and pages and pages of essayish rumination, D. could make you quake in your Raskolnikovian boots–thought and feeling a potent mix, dualism become duelism. I’d like to hear about some other authors who do this adeptly.

Was just re-reading this collection over the weekend. I knew EXACTLY which part of the title story you were referring to but re-re-read it again here anyway. Good post.

Great essay, Kyle.

Thom Jones is one of my heroes. I need another book from him.

Many of Borges’s ‘fictions’ are such “digressions” – except (often) without much protagonist to digress from. Kundera is loved – and despised – for his “digressions” into philosophy, music, and so on. There’s all the business about painting in The Recognitions. Minichillo mentions Moby Dick; I remember (accurately?) swathes of to-me tedious sailing data in Two Years Before the Mast.

I think the brevity of short stories makes a commitment to the satisfactions of information/pedantry less attractive to writers; ‘there’s this story I need to tell’, over ten to 25 pages or so, would often override temptations to expand in less, what, directly narrative directions.

I’d be interested in knowing where Jones got that “Theogenes” story. The only athletic Theogenes I can find is Theogenes (also Theagenes) of Thasos, a pankratiast who is mentioned by Pausanias as having won a significant Olympic victory in (our calendar) 480 BC. Socrates was born in 469 – their lifetimes overlapped, perhaps by decades, both living hundreds of years, as Jones says, after the Homeric epos came together in the form it’s been known for 2 1/2 millenia.

I don’t see how it can matter in fiction that pleasing pedantry itself be fictional, but would it matter if it’s inaccurate? If the effect does not depend on the accuracy of the information, then why is that data specified in the way it is?

There’s that forty page expository digression on glove-making in Philip Roth’s American Pastoral, too, although such is Roth’s skill that it just seems like an extension of the scenes he’s making. Of the explicit essayers, I think Kundera is my favorite, esp. in The Book of Laughter and Forgetting and The Unbearable Lightness of Being. But, you’re right, you don’t see it much in short stories. And the essaying is one reason some of those Thom Jones stories are so long.

One place you do see it more often in stories is at the very end — i.e., Richard Ford’s “Communists” or Alice Munro’s “Friend of My Youth,” where the essaying at the end very much makes the story. This is a different move, though, and probably deserves its own post.

I don’t know the answer w/r/t historical veracity. But let’s say Jones made it up. I don’t care. He’s specified as a means of rendering authority within what Henry James called the donnee (the ground rules, let’s say) of the story. On story-terms, it’s true if we’ve been convinced it’s true.

Not everyone will agree with what I just said. I do or don’t, depending on the context. Like: One time I couldn’t read a Joyce Carol Oates story anymore because she messed up the geography of Palm Beach County, which is where I grew up, so I couldn’t believe anymore.

Thom Jones is good.

Well, it’s a long conversation. But I did make the distinction between fictive and inaccurate.

Of course stories are no less pleasurable, nor informative, for being made-up.

But references that aren’t made-up – say: to the battle of Austerlitz, or to the world of ancient Greece – stand before the writer and reader with, in my opinion, a factuality that’s violated either to the gain of problematizing ‘facts’ or at the cost of that narrative’s purchase on one’s imagination.

Like you’re saying: It’s a long conversation. I agree, but with caveats, most of them having to do with the context in which the writer violates the historical “facts” and the relation of the facts to the rest of the story and how the writer presents them and how the reader is or isn’t cued into them and how freighted the history is in the consensus of the audience (I know that’s problematic) and half a dozen other things, too. Ancillary to the discussion: Yoknapatowpha, Edward P. Jones’s The Known World, almost all of Toni Morrison and William Styron, Homer, Dante, The Hebrew Bible, most of Vollman’s fiction, Welty, Harry Mathews, Dostoevsky, etc.

[…] Minor posted “I Like It When Thom Jones’s First Person Narrators Break Into Essay in the Middle of a Short Story” yesterday at HTML Giant. He makes a great point about where we can really go with first […]

Thom Jones is good.

Not to make sweeping generalizations, but I wonder if it has anything to do with a sort of American pragmatism, seeing that a lot of the essayish writers aren’t American–Borges and Kundera, for instance, or Primo Levi, who also comes to mind. Maybe there’s an “on with it” sort of restlessness that pertains particularly to the short story with its inherent compression, an impatience with too much idle rumination. We’ve got stories to tell, fields to plant, bridges to cover, miles to go before we sleep. If we compare the Best European Fiction 2010 with the Best American Short Stories 2010–both of which are excellent–we see some distinct differences in trend. Take the opening of Lori Ostlund’s “All Boy”: “Later, when Harold finally learned that his parents had not fired Mrs. Norman, the babysitter, for locking him in the closet while she watched her favorite television shows…” etc. Compare that with Toussaint’s “Zidane’s Melancholy,” which reads like an essay on a soccer player’s headbutt, or Giedra Radvilavičiūtė’s “The Allure of the Text” (even that title), with its first line, “I have several criteria for determining the quality of any effective text.” Of course I’m cherry-picking, but maybe there’s something to these tendencies. Roth’s exception, from what I recollect, would fit well (pun, yeah), insofar as the glove-riffing adheres to something manifestly practical and productive, i.e. the manufacturing of goods, something that belongs to a Newark and an America that Roth finds to be fading into a Johnny Appleseed-like past (if they ever existed at all).

[…] Pale Fire Bonnie Jo Campbell and the Strategy of Negation Here is and Obscure Book of Poetry I Like I Like It When Thom Jones’s First Person Narrators Break Into Essay in the Middle of a Short S… Dept. of Arbitraryish Statistics: Three Variations on Three-Act Structure (Coetzee, Roth, Schlink) […]