Random

I STILL DON’T “GET” POETRY READINGS

A few weeks ago, I gave poetry readings a hard time on HTMLGIANT. When I wrote the article, I was aware of its potential to generate conversation. However, I had no idea just how much conversation it would generate.

To everyone who participated in the conversation, thank you. I can’t say that I liked everything that everyone had to say (just as many of you didn’t like what I had to say), but that’s okay. Everyone’s allowed an opinion. In fact, as creatures of language, it’s impossible for us not to have opinions because language relies on difference in order to make meaning; or at least that’s what I think Derrida would say. It’s only sensible then that our opinions (not just yours and mine on this particular matter but everyone’s opinion on anything/everything) should often differ.

To get to why I’ve titled this article “I Still Don’t ‘Get’ Poetry Readings,” though, I’ll tell you it’s because I don’t. I don’t “get” poetry readings. I don’t “get” them not for a lack of trying. I don’t “get” them because I don’t understand what readings hope to achieve within the broader framework of culture. I’ve been to many poetry readings, some of which have moved me so deeply that I cried (Tomaž Šalamun) and some of which have failed to reach me (though also not for a lack of trying). Despite how very different poetry readings can be from one another, I’ve noticed that they all share the same quality of autonomy. It seems to me that the poetry reading desires to be a space that exists for itself and through itself. My complaint, however, isn’t with the poetry reading’s desire for autonomy but rather with the inaccessibility this desire creates.

In my last article, the solution I was pushing for was to make poetry readings more “accessible,” more transparent. Here, I’m pushing for the same idea. Accessibility is what defines the Electronic Age in which we live. Accessibility is about mass consumption, and mass consumption is about power.

In this essay, as well as in the last, I’m urging poetry readings to actualize their full potential: to realize their power.

I’ve read through all the responses to my first article on both HTMLGIANT and Facebook (no, I’m not friends with Hoa Nguyen, but her wall is public), and I strongly feel that my last essay was deeply misunderstood. To clarify the position of my last essay, I’ll respond to a few of the responses that point to its underpinnings.

I think the response that best contextualizes my first article and the meaning I intended it to summon forth is this one:

I’ll point to the detail that the first sentence is evaluative (meaning it’s likely to offend), and, as far as I can tell, there’s no real research out there that either proves or disproves the null hypothesis that states, “Americans are stupid.” I’ll also point to the possibility that the assertion that Midwesterners are the least well read of all Americans is meant to be a jab at me; I’ve never considered Colorado a Midwestern state, but in researching the matter, I discovered that it’s not necessarily unfair to categorize it as such. However, the cardinal detail of this response is neither that “Americans are stupid” nor that Midwesterners are the least well read of all Americans; rather, it’s the statistic that “only 47% of American adults read a work of literature (defined as a novel, short story, play or poem) within the last year.” This statistic is real and comes from a study conducted by the National Endowment for the Arts, titled To Read or Not to Read: A Question of National Consequence. Also, according to another survey conducted by the NEA titled Reading at Risk, “poetry was read by 12 percent of adults, or 25 million people.” My point here though isn’t that poetry is dead. I didn’t kill it. This argument, if it can even be called that, is dead. It’s been done.

I’ll elucidate why I feel the above response accurately contextualizes my first article; although I wouldn’t go so far as to say that we are a postliterate society, we’re undeniably moving in that direction. I’m sure you’ve heard it said that media has a strong influence on our youth, but I can’t even begin to tell you how real that influence is for my generation. I’ll return to this point in a moment.

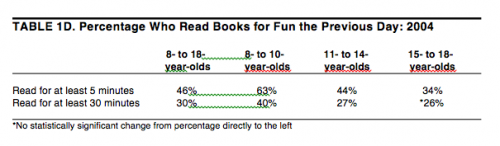

In To Read or Not to Read, the NEA reports the following statistics:

What’s more alarming than these grim statistics, however, is the fact that “TV-watching consumes about half of the total daily leisure time of all Americans ages 15 and older.” What this means is that rather than reading all seven volumes of In Search of Lost Time, my generation is watching all seven seasons (soon to be eight) of Keeping Up with the Kardashians. So, in lieu of reading—and thus learning through observation the difference between “who” and “that,” “literally” and “figuratively”—we’re watching TV, where we learn that it’s socially acceptable to treat the word “literally” as though it were the new “like.”

We learn a lot more than that though. We learn that if we use AXE body spray, women will come crawling on their hands and knees from around the world just to mate with us. Us! We learn that if we have dandruff, we are shameful. We learn from Abercrombie that we can’t be “cool” if we can’t fit in their clothes. A friend of mine, who emigrated here from China as a child, even learned how to speak English solely from watching television, as neither of his parents could speak the language. We learn that media, memes, and celebrity gossip are cultural and social currency. We learn that social media is the new moon and the next frontier; it’s a space race that’s all about being the first to post (and so unearth, excavate, and lay claim to an artifact) the next Grumpy Cat, Bed Intruder, or Old Spice Guy.

But what’s more horrifying than the spectacle of popular culture and its tendency to move toward reduction, stereotypes, and generalizations is the fact that reading is on the decline. I say this is horrifying because reading informs culture. Text and theory provide us with intelligent ways of looking at popular culture, of looking at the world. However, if our youth (myself included) doesn’t have the right tools with which to decode popular culture, how can we expect them to understand that TV is not “real” (but what’s reality anyway)? How can we be expected to treat media images and projections as anything other than real? We can’t. We can’t because we can’t shake this oceanic feeling. We can’t shake our belief in the American Dream, which instills in us a voracity for the silver screen and the things it promises: fast fame, fast money. And so, unable to distinguish between the boundaries of media’s glossy, airbrushed legs from our own pale twigs, my generation is dangerously beginning to collapse, and thus redefine, the concept of “reality” into that of “normality.” The resulting, homologous treatment of these concepts is what I find most terrifying.

On that note, the responses to my first article that most interested me were those that commented on Girls and popular culture in general. Here’s one comment that touches on the topic, in fact on everything I’ve been trying to say:

I think this is a good comment, an astute comment, in that it recognizes the tension that exists between the incredibly rigorous intellects of my mentors (not to mention those of my peers at CU) and the populist nature of popular culture. I realize here that the author of this response is talking less about this tension and more about me, an MFA who appears not to have learned the things she should’ve in her course of study. However, what interests me more than the author’s flaying of me is her hierarchical positioning of poetry over popular culture. I believe this impulse to position poetry over popular culture arises because these two concepts are inherently tied; they are two sides of the same coin.

In what I recognize is an act of reductionism, I’ll simplify this metaphor by calling one side of the coin intellectualism and the other side anti-intellectualism—I use the latter nomenclature for lack of a more precise term. In this article, I hope to redefine this term by housing within it both its traditional definition (a viewpoint that is hostile towards intellect, intellectuals, and intellectual pursuits) and any and all media that can be called or relates to popular culture. The reason I place media under this umbrella term is because of its tendency towards reduction and simplification, which is an inherent feature of most anything that’s intended for mass consumption.

While the American population certainly draws from both sides of the coin, our favor leans towards anti-intellectualism. The statistic that only 47% of all American adults read a single work of literature for pleasure in the year 2005 serves to prove this point. Also in support of this point is the fact that while New York City’s public schools were in the midst of a hiring freeze in 2009, Kim Kardashian’s net worth was estimated to be about $35 million during the same year. Here, I’d have to disagree with the maxim that states, “Corporations are not people; money is not speech.” The majority of our expendable time and income is being given over to anti-intellectual pursuits, which is why I chose to draw from VICE and Girls because that’s where many other people are drawing from as well. Poetry shouldn’t be thought of as being any better or lesser than popular culture. This kind of thinking is detrimental, especially to poetry. The two coexist. They inform one another. Hopefully, one day their relationship might even become symbiotic.

But currently, it seems to me that the intellectual side of the coin is waning while that of the anti-intellectual side is waxing, or perhaps it’s simply maintaining its side of things. Either way, the NEA’s statistics and findings do demonstrate that the intellectualism that literature (of all sorts) has to offer is becoming increasingly overshadowed by the Grumpy Cats of anti-intellectualism.

My problem then isn’t with poetry per say; it’s with culture and hierarchical thinking. With so many incredible intellects in the literary community (Nguyen certainly being one of them), I wonder why we (as a nation) allow popular culture to be the paramount informer. Why are we silent when the spread of TIME Magazine’s “The 100 Most Influential People in the World” favors celebrities above all else. I find it hard to believe that Jennifer Lawrence is more influential than our nation’s educators. I also find it hard to believe that Gwyneth Paltrow is the most beautiful woman in the world (according to People Magazine). Furthermore, I wonder why we allow figures like Kim Kardashian, Brad Pitt, and Ke$ha to serve as role models for our youth when so many brilliant minds and qualified talents exist in the spectrum of society at large, not to mention the great and many minds that exist within our literary community alone. Of course I understand that capitalism has everything to do with the answer to this question, but I guess I’m a product of my generation. I’m an idealist who’s suffering from a bad case of that old oceanic feeling. I have an unshakable belief in the American Dream. I have an unshakable belief that things can change: that we can change.

I think that poetry readings at universities are a great place to begin making that change. As opposed to smaller readings that take place off-campus and seek to engage an audience that is more advanced in their understanding of and commitment to poetics, a greater number of individuals who are new to both fiction and poetry—and who are especially new to contemporary literature and to the concept of a literary community—attend university readings. I think this is a wonderful opportunity to make those who are new to the community feel welcome and help foster their interest in literature.

I believe accessibility is achievable if we take the time to consider what points of access give our youth the tools they need to “get” poetry and poetry readings. I don’t know exactly what form these proposed points of access will take, but I do know that providing the listener with more than one point of entry to a poem or performance is of the utmost importance. Maybe such points of access look like a post-reading workshop where those interested can learn how to bind a book. Or maybe points of access can be created simply through storytelling.

Our students (and my generation) are curious, but they are afraid of poetry, of the what’s not readily accessible and ready-to-wear. I think if we could engage them even more, we might be able to give them the tools with which they might conquer their fears. And who knows how the world might be bettered by an increase in readers? Perhaps we might one day live to see poetry go viral.

***

Bethany Prosseda currently lives in Brooklyn. Obsessed with all things writing, she is most recently employed by a manufacturer that specializes in the production of name-engraved pencils. Her primary responsibility involves sorting pencils that boast uncommon, and therefore monetarily unsuccessful, names such as ‘Xavier’. When not sorting pencils, she can be found singing hits from the 90s at karaoke hotspots. She still watches cat videos on YouTube.

Tags: Bethany Prosseda, Hoa Nguyen, poetry readings

“Getting what people say, for example, may be complicity, may reveal you are a member of a cult; or colluding with someone to protect yourself from unwanted experiences; or that you prefer agreement to revision or conflict. And this might mean, in this context, not always assuming that there is an it to get; living as if missing the point–having the courage of one’s naivety–could also be a point” (Adam Phillips in his essay “On Not Getting It” 38).

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i3MXiTeH_Pg

I would take issue with the notion that off-campus/off-site poetry readings find an audience much more adept to the art. My experience is the other way around. Granted, my work is much more allegorical. While I don’t advocate writing or creating art with the purpose of making “pop” art, we need to strive to adapt and use the medium for a present and relevant use. Readings are super useful for the poet, because we see what really plays and what doesn’t.

I view them more as an exercise in revision and practice (performance and writing) than anything else. I think we need to look at the purpose of readings rather than advocating or eschewing the presence of them.

“In this essay, as well as in the last, I’m urging poetry readings to actualize their full potential: to realize their power.”

If I didn’t think that you were actually urging people to pay more attention to you, I’d say this is one of the most illiterate–both culturally and literally–statements about poetry readings I have heard or read.

It sounds like all Bethany wants is less challenge, more slam poetry. That comes off as a knock on slam poetry, I don’t intend it to be. But slam seems to embrace the ‘performance’ and ‘accessibility’ and ‘pop culture relevance,’ the digestability that Bethany seeks. So here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PSf39y4wnyw

A poetry reading, while still completely valid as an aesthetic medium, is a consciously self-limited way of presenting work. The poet is asking a lot of her/his audience, not the least of such is coping with the oppressive social awkwardness of sitting in a mostly silent room, listening to a sole voice intone from text which–though intimately familiar to the owner of said voice–is often new to the listener. It is also incumbent upon the listener, in these situations, to register and keep the poet’s implied meter (which, it must be said, the poet him/herself is often forgiven for tripping over).

While the argument can easily be made that this type of engagement makes poetry readings “challenging” (and–by a commonly held, if debatable, association–therefore “intellectual”) it is little wonder that attending these events is often considered, by orders of magnitude, less “fun” than comparable activities, such as attending a live music event. It is only through an association with the past and/or calculated self-seriousness that today’s poet altogether avoids the “fun” elements (including, but not limited to, “stated” rather than implied rhythm–by a percussionist, drum machine, or metronome–melody, visual accompaniment, presentation through multiple voices, etc.) on the grounds that they might “trivialize” or otherwise dilute the “purity” of the poetry reading as medium.

Ahem: “More American Adults Read Literature According to New NEA Study

January 12, 2009

Washington, D.C. — For the first time in more than 25 years, American adults are reading more literature, according to a new study by the National Endowment for the Arts. Reading on the Rise documents a definitive increase in rates and numbers of American adults who read literature, with the biggest increases among young adults, ages 18-24. This new growth reverses two decades of downward trends cited previously in NEA reports such as Reading at Risk and To Read or Not To Read.” Your essay is premised on old views.

One can also read analysis which questions the NEA’s methodology, what media counts as reading and/or the history of how literacy is perceived (hint: it’s tinged by class tension and hyperbole). One could also pay attention, or mention, the ongoing slam and spoken word scenes, Sister Spit, etc. etc. and many actual contemporary poets with actual fans in the actual popular culture. Or how Henry Fool remains a popular cult hit for a reason.

One could also not poetry has been nearly dead, struggling against pop culture, has been an ongoing topic for ages – see “Terence, this is stupid stuff” by A. E. Housman back in 1896. There’s also the endless ribbon of “how do we bring poetry to the people” essays, often written by those who don’t recognize their own limited and perhaps problematic perceptions of the people and art.

Culture is far more than intellectual obscurity on side and celebrity on the other. There’s a spectrum within a multitude of popular and obscure items thrive and fail. Poetry persists by being somewhat unquantifiable in terms of worth and reason for existing.

Meanwhile, embracing Girls and Vice Magazine and memes may not connect pop and high art, or make one a literary populist but just be a variant on having a limited set of references. One which results in a semi-coherent second essay about poetry readings which has only a glancing reference to one poet (plus a worn out cliche about people not reading all of Marcel Proust, as if they ever did) but two to Grumpy Cat and ends up with marketing speak about poetry going viral. I mean seriously, is one not a little embarrassed by how trite that is?

I suggest the reason poetry readings are hard to get is not society, generational or whatever, but the traditional inattention to much beyond that which flatters preconceived notions of self-regarding lit major discontent. This myopia makes for trite, vague pontification and does not point to an ability to get poetry or appreciate its place. The world is big, poetry is varied and to get it requires at least using google to ensure one is citing the most recent stats on literacy.

I don’t understand why we’re talking about “poetry readings” as though they’re a singular thing. I’ve been to ~500 readings in my life, and participated in maybe 100–200, and have seen a lot of variety on display. Along which lines, here’s something I wrote on the topic a few years ago: “Why Do We Have Readings? (A Polemic).”

Also, this might—might—be relevant: “Alternative Values in Small-Press Culture.” Peace out, A

It sounds like poetry readings as good as tv is what today’s youth want.

Mass consumption is “about power” to the extent that it’s about obedience.

Resistance to mass consumption might also be “about power”.

I genuinely believe that readings, even poetry readings, can be interesting and thoughtful and memorable and a decent use of a person’s time. more often than not, I am more or less unmoved by them, but after a while, you stop wanting the average poetry reading to make sense or be entertaining like they’re some kind of spectacle, and start enjoying them for what they are, a hush voice reading alien words to you in a microphone.

[…] I STILL DON’T “GET” POETRY READINGS […]

2008/2009, The Nomads of 4th Street, out of Long Beach, California, consisting of three poets, with the occassional guest performer, consistently packed shows of a diverse audience. Including high school students, gang members, college professors, and people who generally did not like poetry too much.

They sold books at these shows.

They appeared in local publications.

The issue is not poetry itself, but within the community, from the “high art” poets to the “slam poets” — there is a middle ground. There are artists who are not one or another, but a bridge.

As someone who performed with the Nomads, I have seen this first hand. You do not have to sacrifice any of your… “artistic integrity” to bridge the gap. You (the universal You) just have to diversify your experience. This includes what you consume as entertainment. It is OK to watch TMZ or read a bunch of comic books. But you should also read Noam Chomsky, Zinn, Steven Johnson, etc. Also check out your local newspaper. Head over to the inner city. Then go visit a farm in the middle of nowhere. Then maybe head overseas, or meet a lot of International people. That is the quickest way to open your mellon up.

Poetry readings aren’t the problem, the poets are.

I can’t continue reading about Greek mythology references. That well is pretty dried up at this point. I hear Africa has a pretty deep mythology as well. (Didn’t ancient Africans also instruct Greek philosophers? Yes, Timbuktu.)

What he said.

[…] La société post littéraire c’est aussi ne plus savoir ce que tente d’accomplir le geste de la lecture publique. […]

[…] I STILL DON’T “GET” POETRY READINGS | HTMLGIANT […]

feigned ignorance is infuriating and a terrible way to frame an argument

I totally get poetry readings. Ask me anything!

[…] at the venerable HTMLGiant, Bethany Prosseda wrote an article called “I Still Don’t “Get” Poetry Readings,” which is a follow-up post to her original “I Don’t “Get” Poetry Readings.” In the more […]

Why are poets so self-conscious about this? It’s like we’re asking for our own end. No one asks why musicians play music, why comedians perform. Maybe a performance can be entertaining and intellectual.