Mass Effect and The Self-Imposed Strictures of Interactive Storytelling

In an era of broad canonical redefinition, when more and more previously marginalized forms, from comic books to slash fiction, are receiving the literary attention they have always deserved, one storytelling medium remains stubbornly difficult for anyone, even its devotees, to take too seriously. That medium is gaming, and I’m afraid that it’s all my fault.

I am a gamer. I have, admittedly, much more passion reserved for gaming’s potential, its Platonic ideal, than for any of its present, more or less imperfect incarnations. Sadly, my attitude toward such an ideal waxes cynical of late. Ten years ago, electronic gaming was just starting to emerge from its reflex-test swaddling clothes and make faltering baby steps in a dozen directions exciting new directions, each a distant promise of something previously unseen in the world of art and literature. Today, the bloated man-child of mainstream gaming has all but sunk into a quagmire of the same stories repeated like a tattoo, with more flash and less substance as each year passes, as the intersection of “game” and “story” becomes increasingly cemented in a model that leaves little room for the kind of progressive storytelling originally promised. Its syntax, the language of player interaction in which its message is couched, has become lazy and predictable. The once promising child’s development may be permanently arrested, and I, as a gamer, am to blame.

In a McCluhanian nod, that syntax, rather than the literal story being told, is the true carrier of gaming’s message. It’s the push-pull between the intentionality of the game designer, as expressed in the structure (digital or physical) presented to the player as “game,” and the player’s own investment and empowerment within the narrative. It is, in many ways, a revival of the call-and-response communal storytelling of folklore and early theater, except that, in a gleefully postmodern twist, the storyteller hopped a jet out of town months before the audience even arrived. The “story” is the sealed and packaged structure left behind, its white spaces carefully measured, the player’s responses anticipated and, in many cases, artfully curtailed. The syntax encompasses both the (always limited) means by which the player is allowed to respond to the piece—say, by rotating the camera, jumping, pulling levers, pushing boxes, et cetera—and the degree to which the storyteller has correctly anticipated, and provided appropriate responses to, the player’s interactions. Games that employ the same syntax cannot help but deliver the same message, over and over, no matter what the “story” appears to be on the surface.

Critically, the syntax is always imperfect (otherwise, the game would be a perfect simulation of real life, which would negate the game designer’s authorial intentionality and, in any case, be unplayably boring). A great deal of gaming’s storytelling potential lies in the allowed-but-unanticipated interactions, the frontier spaces wherein the player becomes more than a marionette acting out canned responses and takes on a more active, improvisational role. Not that this always occurs within the game itself.

Theoretically, games could be as broad in their form and intention as the written word. However, the vast majority of mainstream games occupy a stiflingly narrow syntactical space, forcing the player to repeat the same deeply worn gestures ad infinitum. First- and third-person shooting games—often, the only difference is whether the protagonist’s legs are visible—dominate the home console market, with action-adventure titles in the style of Devil May Cry and God of War picking up most of the slack. On computers, the preferences differ, but the tropes are no less ingrained. With 90%-plus of a game’s syntax devoted to the art of war, you can imagine the narrative range allowed.

The gating factors of syntax aside, there is a deeper problem preventing mainstream gaming from establishing itself firmly in the realm of serious storytelling: the interests of gamers, even those who look toward the horizon, are simply counterproductive to good storytelling. Put another way, people don’t play games, even story-driven games, with the same expectations and motivations as they would read a book. Gaming attracts and rewards certain personality types and behaviors; in fact, it trains those behaviors, in a Pavlovian sense. Gamer’s want to win, they want to win completely, and the act of playing the game reinforces those desires and expectations.

When I play games, I want to talk to, collect, and do everything that the game allows. I am not a competitive person; rather, I’m driven by a desire to fully appreciate the game’s construction. If there are multiple endings, branching options, I want to see them all, and I want to see my time and effort rewarded. The problem is, these desires just don’t make for very interesting or effective stories; I am incapable of acting in my own best interests in this regard. Even those games that attempt to push the envelope ultimately have to succumb to the gamer’s demands, or they will not get played.

And worse, as a gamer, I do not actually want what I think I want. For the past decade, video game publishers have consistently pushed choice-driven storytelling as a key feature in their major releases, and it is clear from consumer response that this is something most gamers think they desire. From Fable to The Walking Dead, Deus Ex to Dishonored, the message is clear: gamers desperately want a part in the story being told; they want to feel as though their interactions matter.

EA and Bioware’s Mass Effect series lives up to this promise better than most. From the first release of this space epic trilogy in 2007, the series has placed an emphasis, almost to excess, on player-defined storytelling that is both novelistic in its scope and cinematic in its execution. The series offers a roughly even split between kinetic over-the-shoulder shooting and loquacious story content, during which the player is bombarded by constant dialogue choices utilizing a “conversation wheel,” via which players can select the tack, though not the actual content, of their in-game avatar Commander Shepard’s responses.

In an effort to differentiate itself from the played-out Manichaeism of most choice-driven games, Mass Effect offers a trio of responses to most situations: a noncommittal neutral option, a by-the-books “Paragon” choice, and a loose-cannon “Renegade” selection. This does little to disguise the fact that the system remains essentially two-sided, with Paragon and Renegade mapping fairly effortlessly to the supposedly outdated notions of good and evil, particularly as the series wears on. This is merely from a gameplay perspective, of course; while the actions themselves do not change much, the moral framework surrounding them does.

In one minor encounter, a brother and sister are squabbling about the woman’s as-yet-unborn child. The child’s father has recently passed away due to a rare heart condition, known to be genetically inherited. The brother wants the child to undergo in utero gene therapy to eliminate any risk that he will develop the same condition later in life; however, the procedure is still new, and may (or may not) introduce its own complications in adulthood. Naturally, the siblings leave it to Shepard, a total stranger, to decide the infant’s fate.

Most choice-driven games present decision points that adhere to such larger-than-life extremes that there is no decision to be made, because both actions fall so far beyond the bounds of lived experience. Detonate the reactor, killing millions, or invent a new, clean power source; the choice is so overmagnified that it reflects little on the player. Mass Effect has these as well, but interspersed among them are game-defining moments that give the player actual pause.

What is significant in these moments, and consistently missed by game publishers, is that the gameplay consequences of the decision are irrelevant to its real consequence. The choice is not meaningful because it gives you a larger gun or stronger armor; it is meaningful because the answers do not come easily. In fact, choices are made more consequential when they arise from within the player, not from any external incentives within the structure of the game.

The as-yet-unsolved flaw of these games as that they do not provide the multitude of choices they seem to; in most cases, they offer exactly one choice (good or evil?) that is reinforced across each of the game’s decision points. The gameplay consequences of your choices disincentivize switching tracks mid-ride. In Mass Effect, this disincentive is expressed by the Charm/Intimidate dialogue options. These options are not available automatically; they rely on the player’s Paragon/Renegade rating, which increases every time a Paragon or Renegade choice is made. The more consistent progress in one direction or the other, the more likelihood a Charm/Intimidate option will come up during dialogue. These Charm/Intimidate options are invariably better, from a gameplay perspective, than the vanilla choices, though not always more entertaining. They might allow the player to avoid a difficult firefight, get some bonus money or gear, or even talk a team-member off of a metaphorical ledge (if unsuccessful, this central character is out of the story for the rest of the series). In this context, the only “choice” is the order in which the player acts out the canned responses provided by the game designers; in practical terms, it is no different from riffling through a book of poetry and choosing the order in which to digest its contents.

And therein lies the problem. Gamers want to win, and they want to win completely. They do not want to cause the death of a character who accounts for a sizeable margin of the game’s content. If the death is preventable, they will go to great lengths to prevent it, even undoing hours of gameplay effort to make a different choice earlier on. This is bad for storytelling in two ways. One, it means that the suicide in question is only ever good for shock value. It lives on in frightfully few players’ save files; it is not, for the vast majority of players, a canonical part of the Mass Effect storyline. Two, it means that players who are aware of such situations will cease reacting genuinely to the game’s decision points and simply lock themselves onto a Paragon or Renegade track, choosing the appropriate response automatically. Played this way, the game still tells an entertaining story, but the meaningful decisions that the series has crafted vanish; they become mere depots to cash in on Paragon or Renegade points, a treasure chest couched in the form of dialogue.

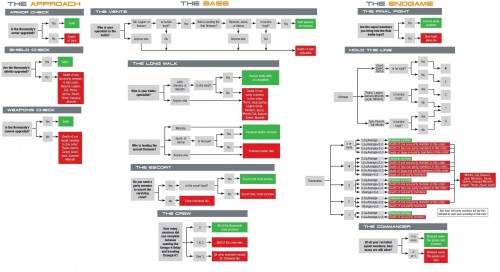

This problem reached its peak at the conclusion of Mass Effect 2. Adopting a structure reminiscent of Seven Samurai, it culminated in a grand “Suicide Mission” utilizing all of the characters the player had recruited and befriended throughout the game. Decisions spanning the entire 50 hours of play go into deciding which characters, if any, survive. In particular, winning the characters’ loyalty in side missions and correctly identifying the 2 or 3 capable teammates (of the 13-character cast) to fill mission-critical roles will result in a surprisingly robust array of outcomes along the spectrum between complete success and total failure. Any of these outcomes that do not result in Shepard’s death can be carried over into the third game.

However, again, the gamer personality intercedes. This thread on developer Bioware’s forums illustrates that, for the vast majority of gamers, even one preventable death is not an option. Gamers want to win, and they want to win completely, even if it means turning their story over to a spreadsheet, even if it means abandoning the consequences of their genuine gut choices—in other words, abandoning everything that they had been clamoring for to begin with. This cheapens, to no small degree, the impact of Mass Effect 2‘s ending, since it always ends in Hollywood-esque victory and explosions.

I will admit that I did the same thing, not just at that decision point, but throughout the 200-hour saga. I kept several frequently updated save files in case I flubbed up earning a character’s loyalty or culminating their romance. I can recognize that a story tinged with loss, with failure, with the occasional bad call is preferable, from a literary point of view, to the happy endings that I invariably get, but I cannot help myself. Video games have trained me to pursue every pathway, keep every team member close, and never accept partial success if a reload is possible. The only way to get me to live with the consequences of my actions is to give me no other choice, and few games are willing to take that risk (the Demon’s/Dark Souls franchise being the chief exception). The games I love will never live up to their potential, and it’s all my fault.

One final note, to close. The vast majority of games fall into one of two categories: player-versus-player, or player-versus-game. Those most concerned with storytelling are of the player-versus-game variety. But it’s that “versus,” that pervasive aspect of competition, that perpetuates the problems discussed above. I believe in the potential of gaming, but I find it unlikely that it will ever be achieved until a new category is formed and populated, one in which “winning” and “losing” are null terms. Until then, my gamer personality will always be there, ready to disappoint me yet again.

***

Byron Alexander Campbell is a writer, editor and intermittent game critic. His fiction has appeared in Polluto, [out of nothing] and the Interactive Fiction Archive. Follow him at theyearisyesterday.

Tags: Byron Alexander Campbell, gamer, interactive storytelling, mass effect

This was interesting. I know what you describe: players (if they aren’t hacking the game itself) will try to hack the story, in which case they aren’t really experiencing it “purely.” It’s competition not only against the in-game enemies or obstacles, but against the game itself. Good point.

I loved ‘Demon’s Souls’. I started out trying to play it as I would an Elder Scrolls game or something, then learned that simply wasn’t possible. I was forced to acknowledge the game’s authority, and it was worth it.

So far, ‘Kentucky Route Zero’ seems like you can’t really “win” in a traditional sense, but you could still try to “win” in the story-hacking re-choosing sense. (The game is not finished, so this may change.) Have you played it?

Journey is what, I think, does it “right.” And games of that philosophy. The story of the game is told IN the playing of it, rather than between it.

[…] How do you know you’ve hit the big leagues? I don’t know, maybe when there are fucking giants involved? At least that’s how I feel when, all breathless and with a gut full of lepidopterans, I find one of my articles published on the awesomely cool HTMLGIANT. It’s a bit of a review, a bit of a criticism, and a bit of a confession, all centered around the question: how far can we possibly push storytelling in video games? Is there a point where we become limited, not by the technology or the medium, but by the personalities of the players themselves? Do those players (myself included) actually want the kinds of stories they keep clamoring for? Find out–well, one person’s heartfelt take, at least–in Mass Effect and the Self-Imposed Strictures of Interactive Storytelling. […]

[…] http://htmlgiant.com/random/mass-effect-and-the-self-imposed-strictures-of-interactive-storytelling/ […]

Journey is an excellent game (sorry about the delay in reply, my Disqus confirmation email was sent to my spam folder). Actually, I think Flower also does a great job of telling a story–or the emotional touchpoints of one–entirely through gameplay. These kinds of “discovery” games that wordlessly place you in a world and let you discover the gameplay and narrative at your own pace, are my favorite genre.

Even Journey, though, lends itself to a phenomenon I’ve noticed tends to crop up (at least when I play) with pretty much every narrative game with 3D movement: there is a disconnect between the narrative urgency and the player’s desire to explore every nook and cranny of the environment. This is accentuated when a game offers hidden collectibles, like Journey does. The narrative might be telling you “Push forward!” and to an extent this is reflected in the gameplay (think of one of the “dangerous” sections late in the game), but at the same time, the gameplay is also telling you “If you take it slow and ignore the threat in favor of exploration, you will be rewarded.”

The only solution to that conundrum that I can think of is when the narrative doesn’t even attempt to pit you against pressing danger (think Myst or Riven) or one that makes it very clear that when it’s time to run, it’s time to RUN–there will be no more little goodies to find. But that’s a subject for another day.