Random

Matt Mullins: Interview

For example, Matt Mullins and Three Ways of the Saw (Atticus Books). The “jagged” school. Certainly Eugene Martin (this book amazing, BTW). Sometimes XTX, Mary Miller, sometimes KGM. Certainly Jamie Iredell. A Hubert Shelby Jr./Iceberg Slim/Patti Smith continuum. Lipstick on the edge of a knife, balls clanking. Thrown/thrown down bottle of flungward. Slash. Krash. You wake up to vomit and your breath smells like burning tires, wonder, jamboree and regret.

Matt Mullins lives in a three-room apartment in a quiet business section of downtown Indiana. His apartment, located in a fifties-futuristic building in sight of four pawn shops and a hat store (That’s not really a hat store, Matt told me), is comfortably unimposing, though it does testify to his days as a traveling musician: souvenirs from Kalamazoo, Mexico, the Eastern Shore, the steppes of Kansas; a bookcase lined with personally inscribed records by Kiri Te Kanawa, DMX, Matt Salesses, Ginsberg (spoken word), Dee Dee Ramone; an entryway in which vintage amplifiers and various guitar cases are stacked shoulder high, as if headlining festival tours of indefinite length were perpetually in the offing.

Our first meeting took place in the summer of 2011. I arrived at his door in the early afternoon, but it was not his door, it was a small bar. There was an elderly woman behind the bar who looked exactly like a cross between a nocturnal monkey and Anthony Perkins. I had a shot of vodka and a very cold beer then asked, “Does Matt Mullins live around here?”

Night-monkey Perkins nodded to the ceiling. “Upstairs.”

I found Matt Mullins newly awakened, his thick brown hair tousled and pale blue eyes slightly bleary; he was obviously surprised that anyone would come to call at that hour of the day. As he finished his breakfast (a Pop-Tart and a grapefruit) and lighted up his first cigarette, his thin, somewhat wiry frame relaxed noticeably. He became increasingly jovial.

“There’s a bar below this apartment, can you believe that?”

“There is?” I said.

“Yes. Let’s go down and have a look.”

We never did get to the interview that day. But there were other days.

SL: Can you talk a little bit about structure and form in this collection? I know it’s in three sections, but I mean even on the micro, the sentence level. I note the longer pieces seem to have more flow and load bearing, more of what Gary Lutz calls “content words” (nouns, adjectives, adverbs, most verbs) in each sentence, while the flash fiction seems to favor staccato bursts and tenser, quicker sentences.

MM: Usually the ideas I’m working with in a given story dictate its structure and point of view. “Bad Juju, 1989” is a story with a disintegrating relationship at its core, so I decided to move back and forth between the couple. “Three Ways of the Saw” focuses on how three people can see the exact same event in completely different ways because they’re each at different, but crucial, junctures in their lives. “The Way I See It,” is an unfolding mystery that gradually reveals an unreliable, though sympathetic, narrator who slowly self-destructs. So the story shifts between police interview transcripts and the final reality of the situation those transcripts imply but still leave open. All three of those stories are structured to create a collective form out of the sum of their parts.

But sometimes structure is simply the unconscious shape a story takes as I try to work my way through it. I don’t know the shape at the start, but then it begins to emerge by the end of the first draft. Then I go back and reshape accordingly, which in turn affects the storyline, which in turn affects the shape, and things kind of (r)evolve organically from there. It’s a bit of a conundrum for me as well. Does the story create the form or does the form create the story? It can lean one way or the other, but for me it’s often simultaneous: The story reveals the form as the form reveals the story.

You make a really interesting point about the longer stories having more flow and the shorter pieces being more staccato. This isn’t always a conscious choice for me. It’s a combination of intuition, pacing and intent. I know fairly quickly if I’m trying to tell a longer story or shorter one, and then I react accordingly in terms of macro/micro structure and form. With the shorter pieces I tend to be going for compression, brief, stand alone images and unexpected leaps or turns. This is especially true of short pieces like “Shots,” “Rest Stop,” “Tagged,” and “I Am and Always Will Be.” With the very short pieces like “Highway Coda,” “Black Sheep Missive,” and “Death of a Henchman,” I’m trying to imply beyond what’s there by causing every sentence to stand alone on its own while I build the story as a whole.

I think I pushed this idea to an interesting place in “Arion Resigns.” Basically, I realized that not only could I try to get sentences to stand alone, I could try to get the parts of sentences to stand alone by chopping them into fragments with periods. This enabled me to “brick-lay” fragment by fragment in a way that kept each sentence’s original intent on the page while also pulling the end of one sentence into the beginning of another. So you have these fragments that stand-alone and longer sentences that run forward and backward across these fragments in various combinations in a way that repeats itself like a snake eating its own tail as it rolls down a hill.

With the longer pieces and the longer sentences, that’s me feeling the expanse of the story and looking for those moments where I can stretch out and start working with aspects of a story’s controlling idea. Those tend to be the sentences where I’m gradually layering assertions or reaching for insights that build to form the story’s theme. With the shorter pieces, it’s one overall idea built in a small burst. So it’s a pop up tent snapping open versus a foundation upon which I build a frame, walls, and a roof.

SL: Who are the living writers whose work you pay attention to?

MM: I like writers who remember the bargain at the heart of the deal, the ones whose writing demonstrates that they believe: “The reader is investing their time in my work. My job is to deliver a compelling, insightful story with an ending that feels fulfilling, resonant, and inevitable yet totally unexpected.” However, I am also a huge fan of stylistic experimentation and non-narrative storytelling where a “story” emerges. So the writers I really tend to admire are those who still remember the bargain at the heart of the deal while delivering a compelling story told in a stylistically interesting way, be it voice or something more experimental. Eugene Martin’s novel Firework comes to mind. I love the voices in Donald Ray Pollock’s collection Knockemstiff. I see him as a direct descendent of the late Breece D’ J Pancake whose Trilobites and Other Stories is one of my favorite books. I also admire Blake Butler’s ability to write from deep inside of a narrator while still allowing the outer shape of the story to emerge. I think the same of Peter Markus’s ability to create large worlds with an economy of words. Writers who can sling a mean sentence also knock me out. Tina May Hall’s book The Physics of Ordinary Objects is beautifully lyric without sacrificing a strong sense of story. And I like writers who aren’t afraid to tell you exactly how they think it is, which is something I enjoy in the writing of Roxane Gay. I also like Ander Monson’s writing. He’s stylistically experimental and has a voracious and critically astute intelligence that informs his understanding of how fiction works, but there’s always compassion at the heart of his stories.

SL: I notice many of these stories set up an expectation, and then we get a quick turn. What’s interesting is neither the character nor the reader expects the turn, and we’re left dazed and needing to collect ourselves. In “No Prints, No negatives,” we think the father is getting assaulted by bikers, and then turn, it’s actually two people having sex in a parking lot. In “Guilty,” it’s such a setup, all the anxiety from the character about getting busted, and then turn, it’s someone else who is caught in a crime. “Rest Stop” is amazing, in how the turn twists and releases the entire narrative. In “The Braid” the turn is devastating. Can you discuss this technique?

MM: I’ve always enjoyed stories that take unexpected turns rather than “twists.” For me, a turn is planted somewhere at the heart of the story, either literally or thematically. A twist feels false and tacked on. One way to create drama in a traditionally “narrative” story is to give a character increasingly narrowing options while ratcheting up the stakes with each choice they make. In all the stories you mention above, the characters make assumptions that are proven wrong. Because those assumptions have turned out to be wrong or open ended, they’re confronted with another, more difficult choice, be it internal or external. Sometimes I like to leave them at the precipice of that final choice. Like I do in “Guilty” and “The Braid.” Sometimes I’ll take them into the next choice, which is what happens in “Rest Stop.” But wherever I leave them, the intent is to imply that the situation or character has forever changed because of the turn. I guess I’m fascinated with that idea of making turns feel surprising yet inevitable as they lead toward moments of change.

SL: What causes you despair?

MM: Cowardice. Which is at the core of everything evil whether it’s humanity’s historical and enduring inhumanity or the unsubstantiated criticisms of people who fear the reality of their own insignificance and therefore lash out at those attempting to do something positive or brave.

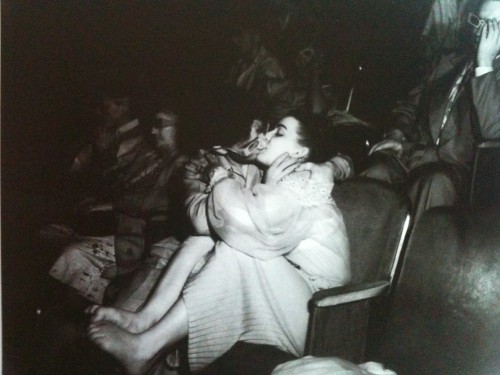

SL: What’s the craziest party you’ve ever attended and why?

MM: Telling you that could get me into all kinds of trouble. But I will say that it was such terrific fun I don’t ever want to do it again.

SL: How do the stories in your collection fit together?

MM: I think they’re all trying to get at a similar thing in different ways: How do we transcend the alienation that exists at the heart of individual consciousness to accept the ironies and consequences inherent to the human condition? Some readers will be able to see this idea at work in the stories, and I’d like to think this collection will appeal to them. Others won’t be able to see how the stories in the book work together to form this unifying idea, or they’ll see it but they have no interest in exploring the idea in the first place. They’re better off reading someone else.

SL: Were there any professors, during your student years, who particularly influenced you?

MM: Stu Dybek was a huge influence on me when I was at graduate school at Western Michigan University. The man can write, to be sure, but he can also teach. His generous command of the classroom, his supportive attitude toward developing writers, and his focus on craft from the sentence level all the way up to the structural and thematic concerns of a story were invaluable. He had a very nuts and bolts approach while still keeping things high-minded. Learning from him was like studying with a Zen master mechanic of storytelling. I was not at all surprised when he was awarded a McArthur “Genius” Fellowship a few years ago.

SL: You are very good at transitions. You are also a screenwriter. Does screenwriting assist you in this area?

MM: I think so. One of the techniques I use in both screenwriting and fiction is to place a substantial story event in the unwritten space “between” scenes. Set up the exit from the one scene and the entry to the next scene in the right ways and that unwritten scene comes alive in the reader’s mind. This works to the writer’s advantage because nothing is more powerful and more flexible than the reader’s imagination. In that regard this technique also gives the reader a certain amount of creative power and control over the narrative; it allows them to visualize, bridge the gap, connect the dots. That’s the kind of engagement that pulls people into a story, or a script or a poem, for that matter. Those leaps.

On a practical level, effective transitions are a matter of expedience. With more traditional narrative structures, the narrative line of a story potentially contains all the elements of plot and character in the back-story as well as all the elements of plot and character that evolve from the point of attack forward across the narrative spine that connects the story’s inciting incident to its climax. Unless you’re writing something “epic,” you’re not going to dramatize all of this. You’ll find other ways to weave in that essential information via exposition and drama/conflict in the story’s “now.” So you must plot. You pick and choose when to enter the story, what scenes show, how to organize those scenes to achieve the desired impact dramatically and thematically. But you also choose what to leave out; and, more importantly, how to leave it out. Writing in such a way that you can cause the reader/audience to visualize and understand events you didn’t actually put in the story is one way to tell a “bigger” story in a shorter space. This is important to both the short story and films, which are meant to be absorbed in one sitting.

This same idea helps bring resonance to an ending. If you can pull this technique off between scenes, you’re likely to be able to do it at the end of a story as well, but you just let that final chord and the situational and thematic implications you’ve established ring instead of playing on like you would if you were still inside the story. There’s much more to a successful ending than this alone, but the approach can be an element of an ending that works.

SL: I notice you publish in print and online venues. What do you think about what’s going on online these days, as far as the literary world?

MM: Overall, I think it’s empowering for both writers and readers. It’s been great to see online journals come into “legitimacy.” The internet has essentially broken down the walls and expanded literature’s reach. If literature is meant to make people think more deeply about the human condition, increased access to a wider variety of literature has the potential to create greater cultural and social change. I mean, more people reading thoughtful things can lead to more thoughtful people. And that’s a good thing. Also, writing is an isolated pursuit. Online literature helps lessen that isolation through cross-pollination. The internet potentially enables me to stumble across some obscure concrete poet from North Korea whose work I’d have never seen otherwise. This writer might blow my mind with new ideas that inform my own writing. Multiply that by all the readers and writers discovering new territories and talking with each other about what they’ve discovered, and you have a wider variety of aesthetic approaches that pushes boundaries and builds community.

I’m also very much into multi-media and interactive literature like the kinds of things I’m doing at lit-digital.com. I certainly hope that the book as a physical object forever remains, but there is no denying that literature has also gone beyond the page. The internet makes interactive literature possible. A well-designed literary interface allows the creator to put across specific ideas while also enabling the reader/user to directly participate in and even take control of the experience. That goes way beyond the typical writer/reader transference.

SL: There’s a lot of driving in this collection, a lot of motion: discuss.

MM: I have asphalt in my veins. The car has been a central presence in my life. I was raised in the Detroit area. My family often took long road trips when I was a kid. My father worked for one of the Big Three. Some of my girlfriends in high school and college lived more than an hour away. I’ve had a number of jobs with very, very long commutes. My family is spread out all over America. My disposition is such that I like to drive long distances with the radio off to let things jangle around in my head. I’m forever curious about what’s around the next corner. The possibilities of the road, sublime and terrific, have always fascinated me. And I’ve learned one thing: If a cop ever pins you down to the shoulder, approaches you through your blind spot, and asks you the ubiquitous cop question: Do you know why I pulled you over? You should not respond, “Will you let me go if I answer correctly?”

SL: “Shots” is an eerie story. It seems to exist in subtext, and you really caught the remorse and vague uneasiness of a hangover, especially one from extreme drinking. But “Shots” goes a bit deeper, into some thrumming danger. Do you remember drafting this story, the process? Can you talk about subtext?

MM: “Shots” is one of the older stories in the collection, so I don’t fully remember drafting it. I do remember one of the first things to emerge was that odd image of a Jimmy Carter mask. The writing on the protagonist’s feet also intrigued me. So did the idea of overdoing it and missing out, and the idea of reaching for intangible “answers” in that same way people on LSD seem to feel they’ve solved the universe only to come down with the shreds of that beautiful balloon in their hands. I’ve been in bands throughout my life, so there was also a desire to describe this wonderful feeling I get when I’m fortunate enough to play with talented people and we start improvising and the music takes on a collective yet singular life that somehow transcends our individual contributions. “Shots” is also one of the first times I used the technique I mention above, this idea of the scenes we don’t see, but the gap is literal in this instance because the protagonist has passed out. As for the subtext, I suppose there’s danger in our forgetfulness, in our self-indulgence, our self-absorption, our insulation, and our resulting indifference to the larger situation. Regret is eerie, especially when you can’t tag its source.

SL: What do you think about readings?

MM: I have mixed feelings. On one hand I think the writing should stand alone on the page and therefore the writer as reader should be concerned with doing justice to that language through a reading that emphasizes the piece’s ideas and flow without using their personality as a tool of distraction. As a musician the sounds of words and the rhythms of sentences are also of concern to me—when I’m reading I often feel myself swept up in the rhythm of things, feel my mouth shaping and launching sounds—so I tend to think the writer has an aural responsibility as well. That is, part of the job is to bring out the sonic beauty of the language in a way that enhances its meaning. In essence, I’m trying to read the song of those words in the same way I heard them in my head. When I’m of this mind I think the writer should stay the hell out of the way and become the instrument while letting the story be the player. Personality and performance be damned.

Then I go to a reading and someone “performs” their writing, and I don’t mean performance or slam poetry here, I mean the writer really reads the shit out of their work. Just totally delivers. They’re smart, they’re funny, they’re personable or even nervous in a very charming way, and the force of their personality engages us and allows us to further attach ourselves to the writing. And I sit there in the aftermath thinking, “Damn, that’s how you read. Should I try that next time around?” I’m still wrestling with these two approaches, but now that the book is published, I’m getting more opportunities to read, so I plan to experiment with delivery. Hopefully, I’ll find some kind of compellingly happy medium that satisfies my concerns and the audience’s justifiable expectation to experience something worthwhile.

SL: What’s the worst writing advice you could give someone?

MM: Never allow yourself to write something bad. And. Don’t revise. It was genius the first time around.

SL: One thing you do for a living is teach screenwriting. How do you like teaching?

MM: It’s fulfilling and exhausting. When I have fifty-some students, all of them developing stories at once, that’s a hell of a lot of stories rattling around in my mind. My own ideas can feel squeezed out. But then I see them go the distance and pull off something good. And I think, okay, I am opening the door, just like that door was opened for me in the past. But I’m not going to sugar coat it. It can be a serious grind when you’re in it up to your eyeballs, especially when students are new to the screenwriting form, which is very specific to a degree, and have yet gain a full understanding of how visual storytelling works. But then you step back from it and think, “I am making a living talking about stories, about literature, about screenplays and movies.” And that puts it all in perspective. Literature, the purpose of storytelling, is like religion and philosophy to me. It’s a tool for living thoughtfully, and I feel very fortunate that storytelling and literature are at the center of my current occupation.

SL: Describe a good day for Matt Mullins.

MM: For me, any day that isn’t a bad day is a good day. But that’s not a very interesting answer, so here’s a fantasy good day that combines some elements of good days I’ve had: My good day will start with waking up to no alarm and making it to the desk to write before too many other things get in the way. I’ll make this good day a Saturday, so I can write until I run out of momentum, which tends to be after about four hours. After I’ve left off working on something I’m liking, I’ll resist my bad habits and get some exercise, which could be anything from playing disc golf to rowing to riding my bike around. Done exercising, I’ll spend a golden afternoon with my wife and daughter, preferably outside because it’s always mid-October on this good day with a southerly breeze and turned leaves drifting down. At some point, I’ll call my parents and sisters, all flung out across America. I’ll also forget to be pissed off at myself for the personal failing or inconsequential slight that would normally be spinning on the gerbil wheel in my head. Come evening we’ll have friends over and cook up some badass food from scratch while enjoying drinks, conversation, etc. I have wide-ranging musical tastes. So the stereo will be on and playing anything from Jelly Roll Morton, Skip James or Fela Kuti to Dr. John, Black Sabbath or the Minutemen. If the friends we have over happen to have kids, we let them run amok until the gears wind down. Meanwhile, we’ll talk and we’ll drink and we’ll talk and we’ll laugh as I count myself lucky and mean it.

Post Script: If these friends also happen to be musicians, we’ll eventually go down into the basement and plug in. From there things might go just about anywhere.

SL: Thank you for your time, Matt.

MM: Thank you, Sean. You’re not one to throw softballs.

Tags: Atticus Books, Matt Mullins is a karate man, Three Ways of the Saw

[…] Lovelace interviews Mullins Share this:TwitterFacebookLike this:LikeBe the first to like this post. This entry was posted in Uncategorized. Bookmark the permalink. ← If a Tree Falls… […]

so weird, just picked this up yesterday on a whim. also where is ‘downtown indiana’? is that indianapolis? or like evansville?

Oh it’s a state of mind.

http://lnk.co/IHTX5

[…] were writers, writers, writers, writers. Matt Mullins throwing down the saw, bzzzzzzzzzzzzzz. Interview with Matt here. Matt and I keep thinking of ways to destroy his book. The obvious is chainsaw. Video coming soon, […]