Random

Ocularcentrism, storytelling, and the internet

In The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses, philosopher and architect Juhani Pallasmaa mourns our ocularcentric culture. By ocularcentric, Pallasmaa means a culture made for the eyes, where sight dominates all other senses, where we experience the world through vision alone rather than an integration of all five senses. Pallasmaa argues that second to vision is hearing. The other three senses are ignored almost entirely. This is pretty radical, especially considering that he’s an architect, an occupation focused keenly on the visual experience. And yet, Pallasmaa argues:

Sight isolates, whereas sound incorporates; vision is unidirectional, whereas sound is omni-directional… Sight is the sense of the solitary observer, whereas hearing creates a sense of connection and solidarity. (49-50)

Reading Pallasmaa, I immediately thought of Walter Benjamin and his argument about the end of storytelling, how as a culture, we have lost our memory of oral narrative, which ultimately leads to an inability to communicate orally. Oral stories are grounded in the audio, but even more importantly, they offer a different way of thinking. To tell a story is an art. Whereas I can write novels and short stories galore, I am a terrible storyteller, by which I mean a terrible story-speaker. Why? It’s a way of thinking to which I am utterly unaccustomed. I have grown up in an ocularcentric world, where weight is put on the written word. What is written is powerful. It is permanent. What is spoken is ethereal. It is gone – and forgotten – as soon as it is spoken.

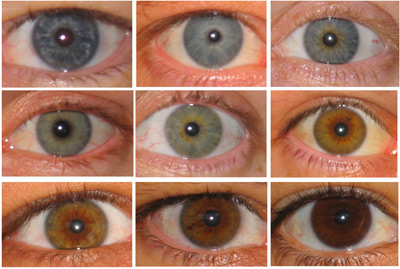

But why the eyes? We have five full and very useful senses! Why vision?

As a society, we put more weight in vision, and to a lesser degree hearing, because the other three senses—taste, touch, smell—are so clearly sensual, and we’re all scared of the sexy. Call us Protestant prudes. But, I mean: Can you imagine a world where we experience things more through touch than sight? Can you imagine distinguishing a person or feeling an emotion more through shape and feel on your skin than by looking at faces? Or their smell? To be close enough to smell and have a nose so keen as to know smell so personally? And taste! Well, I won’t even go into that possibility!

But come on, Lily!, you say. Vision is the most pragmatic method of recognition. And you’d be right. Pragmatically and evolutionarily speaking, sight is the most efficient way to discern shapes, people, things, etc., but Pallasmaa (and I) would argue that vision, as a sense, has come to dominate all other senses, and we have developed an over-reliance on sight, so much so that our other senses have diminished, not only in value but also in use. We hardly use touch, unless it’s sexual/sensual. We like our “space.” We are told not to touch a lot of things. We are told not to touch each other. Think of all the things are not allowed to touch. Our skin—our largest and most sensorially perceptive organ—is out of bounds. Even when we do touch, we use our fingers. What about all that other skin? What about all that possibility for sensation?

And taste: Most Americans are taught that McDonald’s tastes good, and folks, when McDonald’s tastes good, we have definitely lost our sense of taste! Ok, all joking aside, given the constant bombardment of advertising etc that tells us that our bodies are inadequate—or maybe all too adequate—we’re taught and trained to hate food, since food makes us fat and therefore unattractive and therefore ugly and therefore bad human beings.

Smell is equally problematic. Usually, smell only becomes obtrusive when the smell is bad. Good smell is appreciated and then our noses acclimate and just like that, the appreciation, the pleasure of the smell, is gone.

And so, we live in an ocularcentric world. But what does this really mean? Well, it means that we appreciate things visually and we appreciate visual things. We prioritize the visual more so than any other sensory experience and perception. Aesthetics, for instance, are judged visually. How else would you judge aesthetics?

Both Pallasmaa and Benjamin discuss a time before the printing press, a time when information was communicated orally. We had to listen in order to learn, whether it’s information or gossip. Then, the printing press and the whole world shifted. Once information could be disseminated cheaply and widely, people didn’t have to listen so well anymore. Also, reading is more time efficient than listening. Writing is more efficient than speaking. But still, you had to listen for gossip. In order to learn about the juiciest news about a neighbour or friend, you had to open your ears.

But then, my friends, but then, the internet and the whole world shifted again. Now, not only do we not need to listen in order to gain information, we don’t need to listen to learn about the secretest of secrets. With the advent of social networking and chats, emails and blogs, anything and everything we want is available to our eyes. We just have to do a little clicking and maybe a bit of typing and for our pretty little eyes: a feast!

Pallasmaa writes:

The hegemony of vision has been reinforced in our times by a multitude of technological inventions and the endless multiplication and production of images – ‘an unending rainfall of images,’ as Italo Calvino calls it. ‘The fundamental event of the modern age is the conquest of the world as a picture,’ writes Heidegger. The philosopher’s speculation has certainly materialized in our age of the fabricated, mass-produced and manipulated image. (21)

Whereas Pallasmaa really focuses his book on the effects of ocularcentrism on architecture, I wonder what it means for storytelling, not just oral narrative but our understanding of the construction of stories. Before the internet, before the printing press, stories took time and space to tell. The listener required great patience while waiting for a story to unfold. The printing press took away the necessity of space. That is, people no longer needed to gather in order to hear a story. You just needed the time to read it. Now, with the advent of the internet, our stories are becoming shorter and shorter. We need very little time and almost no space to read. We just need a place to set our bodies and our laptops.

Now, I’m not all doom and gloom. I’m not saying this is the end of the story or anything like that. But I am slow to adjust to our newer modes of storytelling, and I wonder what all of this will mean. We are in the middle of an evolution of the story. Where will we go? What will our stories look like? (Look at me! An ocularcentrist!) Do you think the future promises more ocularcentrism? What will it mean? And so, I close with no answers, not a single one, but here, I offer you some pretty things: Pallasmaa’s creations!

Tags: architecture, Juhani Pallasmaa, walter benjamin

I see what you’re saying here.

I’m with you on this one. You can’t really over-emphasize the evolutionary benefits of sight, and our dependence on sight came along well before the printing press or the internet, well before we were even homo sapien. But I agree with you that we’re more and more losing out on our other senses.

I remember on a trip with my uncle to Florida in the 5th grade, we were listening to some hard rock station, or maybe one of his many metallica tapes, and he was playing along on the steering wheel to the drums (he was and is a pretty good drummer). At the time, I remember listening and thinking that it was all just noise. I couldn’t parse out the sounds, couldn’t separate the drums from the guitar from the bass, let alone the unique sounds of the drum kit.

Now, fifteen years and a lot of music lessons and playing and listening later, I can hear all of these qualities. But I have friends and family who haven’t ever done the work to tune up their ears, and they talk about the same issue that I had back then, the feeling that it was all just a mash, a coherent mash, yes, but a mash nonetheless.

Now, the reason I share that, is I think this issue of ocularcentricity goes further than we realize. Assuming we are born with the most basic of sensory capabilities, it’s up to us to choose how those develop. Sure, my sense of smell will never be as articulate as my sense of hearing or sight, but that doesn’t mean it couldn’t improve by leaps and bounds if I started cooking from scratch, started analyzing closely the different scents that I’m exposed to, etc. The same goes for touch, for taste, for hearing, and yes, even sight.

Though we are an ocularcentric society, I think the bigger issue is that we are a society that is okay with sensory generalization. We eat what we eat quickly, without experiencing the nuance. We listen to music distractedly, not devotedly, and not with the tools of a musician, so we lose all the particulars, the nuance, of what we hear. We read a book or a blog post quickly, and lose the nuance of the language. We look at a painting or architecture, and we quickly pass over it, missing the subtleties, or even sometimes the most obvious thing.

We don’t spend enough time in our experiences, I guess is what I’m saying. I don’t know how many times I’ve been reading a book that I’ve had for months, and suddenly I’ll shut the book and look at the cover and, holy shit! I didn’t know that was on the cover. That’s a really cool cover. Does that happen to anyone else?

Anyways, I’m just writing. I really like this post though. And as far as telling stories, lately I’ve been reading to my little cousin when I go home, and even more lately I’ve been tempted to try my hand at making up a story. I think next weekend I’ll give it a shot.

Thanks for bringing this up. Helped me think about some stuff that’s been sitting for awhile.

This is a very interesting post, thank you. I’ve been thinking a lot lately about virtual technology has affected attention span, I hadn’t thought of how visual-centric it is, such a good point. I do feel the internet through my body though, or maybe the sensation shoots fast from ocular=>brain=>molecules deep inside my body. So that I feel this uncanny body intimacy with people I’ve never met in physical timespace (my internet experience being largely interactive). Sometimes I wonder if this is like cheating, that I’m having sensations through mediating technology, rather than experiencing firsthand the smell, taste, feel of others. Sound is still transmittable via audio streams, and the live reading, the recording of the live reading voice seems to be more significant for poets than fiction writers in general, why is this? A fiction writer friend once said to me that people go to poetry readings to hear the poet’s voice reading poetry, but they go to fiction readings not to hear the fiction writer read their fiction but more to ask the fiction writer questions about him/herself as a person. I wonder if this has something to do with the way we culturally perceive intimacy vis a vis poetry vs. fiction. Poetry seems more associated with the immediately sensual, whereas (mainstream) fiction is aligned is celebrity? That’s not how I read fiction though, I read it sensually. I communicate everyday with animals through touch and smell and sometimes taste as well. I do this just as much as I communicate with humans through ocular emails, blogcomments, etc. When I look at the Pallasmaa buildings you posted above, I first see them, and then I feel the space of them around my body, as I picture myself moving through them in my animal skin.

I like this idea of bringing the oracular back into storytelling.

I tried to start a blog today called Attention Surplus Disorder, and it’s already taken.

The end is near.

I think that online we get more of a feel for how people’s diction works, ie the sound of the language now.

Think of reading an old book – – you can still follow it easily, because it’s written or translated in standard English. Now think of how strange it is to read any sort of old book written with characters who speak in dialect. I myself have to read these parts outloud, to try and parse not only the rhythm, but also just the basic meaning. Most of our IMs or gchats are written as we would speak them – – in slang, in lively casual contemporary diction, plus full of visual / written “pwned” style jokes & memes.

And even though we do it without thinking every day, just seeing how we actually speak, seeing what it looks like written out on the page, is so bizarrely disconcerting. Think of automated transcripts. They are weird!

What I think is that it will hinder the longevity of our stories. But make them more fun in the meantime?

Because I want that real used-language in my work. There’s this impulse-buy book, Drunk Texts. It is so rad and invigorating and weirdly hilarious to see what our real daily language looks like on the page! Why is it so startling once it’s on the page?

And for sure I want to learn to write like I speak. But . . . not to the occlusion of clarity. Or longevity. Right?

Very interesting post, Lily. I’ve honestly never thought much about ocularcentrism and its effects on the way we interact with other people and the world around us.

Like you and most others, I’m incredibly ocularcentric. I would say touch played a larger role when I was a kid. I was (still am, but not as much) incredibly affectionate and inquisitive, so I would touch any person/thing I could safely get my hands on. I spent a lot of time “in time out” during elementary school for kissing and massaging my friends and (no joke) hugging trees (I went to a fundamentalist Christian academy, so boo hippies I guess?). However, touch could never trump sight.

Re: oral storytelling, I’ve always preferred the written word for the same reason you give–the oral seems so fleeting. In your ears, on your mind for a few moments, then gone. I like to see what actually makes up the story, I like to re-read sentences/passages that knocked me out, I like to feel the weight of the book in my hands and the pages between my fingers and the way books smell, oh yes. I need all of that.

Nice post, Lily.

Great post, Lily! (Hullo!) If I really look at something, fully focus on a person with my eyes while interacting with them, the other senses become so poignant and activated that it becomes terrifying. But also fulfilling. That tingle feel. Sometimes I don’t want to see anymore, and other times it is a wonderful miscegenation of all the senses that starts with seeing. I suppose my curiosity is: do we only like ( = to feel a comfortable amount of control over) to look in the ostensible secret tense?

Hi jtchandl: Yeah, of course, vision has developed to put us at an evolutionary advantage, no question about that. I’m not saying that vision, as a sense, doesn’t have its major perks, from a survival standpoint. I was more playing with the idea of how our other senses are desensitized, to the point that they’re practically obsolete.

I agree with you that as a culture, we experience sensory generalization. Whereas we are ocularcentric, Pallasmaa makes the argument that vision is very focused. We ignore the periphery. This fits with your examples. We are singularly focused. Pallasmaa gives a very astute example: the agora/market. In the US, there are very few agora/markets, but I remember going to a market in Saigon. I had to be keenly aware of the periphery. That’s where everything happens, and if our field of vision is unidirectional, we miss almost everything. The supermarket, however, is designed for unidirectional vision. We are guided through the store. We walk in and are forced to turn right. We follow traffic patterns while shopping. (Airports are no different. It’s partly for efficiency, sure, but we are also manipulated to maximize our buying potential!)

Pallasmaa and Gaston Bachelard both also speak about the haptic experience, which is way cool, but I’d have to devote an entire post to the concept. I don’t quite have the energy for that right now, but look it up. Provocative stuff! Thanks for your comment!

Hi Roz: yes! Absolutely! I was moving towards the argument about attention span when I discussed how our narratives are diminishing in size, by which I mean word count. There aren’t as many sprawling novels, though we’ve recently had a brief resurrection of the form, which I hope continues!

Your point about readings is really fascinating. There is some truth to it, certainly. In general, I would say that poets are dedicated to sound and the oral/aural quality to their writings more so than fiction writers, esp commercial fiction writers. There are, of course, exceptions. Most of the contributors here at Giant pay careful attention to sound and meter (at least they do to me).

With the memory of AWP fresh in my mind, I’d say fiction writers and poets alike worship at the alter of celebrity. But let’s face it: fiction writers, esp novelists, are more likely to attain wider “fame” than poets. In the small writer-world though, celebrity is celebrity. I’d go to a reading to hear someone I like read AND hearing their responses during q&a.

I bet the person who started that blog has ADHD.

Check out (living) philosopher David Michael Levin. Titles include The Opening of Vision: Nihilism and the Postmodern Situation; Modernity and the Hegemony of Vision; The Body’s Recollection of Being. Very good and very readable.

Often I feel more connected with my sense of hearing. I love listening to binaural recordings, sound art & prefer hearing authors read their work. I cannot write or read with music playing, even instrumental. Sound takes prominence over my other senses & I cannot focus.

Whenever I visit an art gallery, I want to touch the work and even put it in my mouth sometimes. I like that tension caused from the urge to experience the art in prohibited ways. After reading your post, it makes me happy to know my other senses aren’t dormant.

Also, I think tumblr is good evidence of our ocularcentrism— an entire subculture of blogging based on virtual mood boards.

shopping-store.org/

Very interesting post. A little late to the comment field, but I’m curious how this implicates mass media where so often “seeing is believing.” At the same time, politicized news coverage relies on vocalized (and thus oral) interpretations of “news” events and associated images — interpretations that privilege a particular political view as expressed by the voice of the pundit over and above the many heterogeneous voices that might speak if only they could be heard over the mass airwaves.

Interestingly, the tweet in particular, though visual text and not oral, serves as 140-character corrective to this silence, as does the YouTube vid and the Facebook post. Taking these things into account, I would argue that the real tension lies between the supposedly singular image or singular voice speaking from the privileged seat of so-called mass media (a misnomer?) as opposed to the variegated voices and images as captured by the masses in the streets. There is the image that attempts to close down meaning and the image that exists to question and thus open up meanings. There are similarly words (whether spoken aloud or typed as text) that close down meaning and words that question and open up meaning.

The supermarket (as microcosm of the capitalist marketplace in general) is then an instance of meaning having been premediated and closed down in an attempt to channel the consumer in desired directions, partly by spatial arrangement, and also through the use of text and image and the presenting of carefully premeditated binaries (generic or brand name, pick-a-size or full-size, high price point or low price point). The freedoms of the shopper have been predetermined by the singular source of corporate policy feeding the bottom line. The agora or marketplace, in contrast, is a bazaar of possibilities ultimately controlled by no single entity (though it does have its rules and its rulers). It is a place where a variety of sources, including both words (spoken and text) and images, exist together and are even allowed to fight openly against each other. The supermarket allows for a comparatively muted competition of values, prepackaged and annotated with supposed nutrient content and price/unit measure breakdowns. While the supermarket is “safe,” the agora/marketplace encourages healthy skepticism, haggling, and the trust/distrust of human meanings. The supermarket allows for no haggling, enforces take-it-or-leave-it binaries, and is vastly impersonal to increasing degrees. It is channeled where the agora is expansive.

Again, great post for prompting lots of productive thoughts!

[…] Lily Hoang, http://htmlgiant.com/random/ocularcentrism-storytelling-and-the-internet/ […]

[…] http://htmlgiant.com/random/ocularcentrism-storytelling-and-the-internet/ […]

[…] http://htmlgiant.com/random/ocularcentrism-storytelling-and-the-internet/ […]

[…] storytelling, and the internet | HTMLGIANT. [online] Htmlgiant.com. Available at: http://htmlgiant.com/random/ocularcentrism-storytelling-and-the-internet/ [Accessed 17 Jan. […]