Random

Reading Comics: Christopher Lirette on the Dark Phoenix Saga

Welcome to the second installment of my new series: Reading Comics. I’m excited to report that I’ve got a bunch of great contributors lined up, and am myself working on a few entries. If you haven’t contacted me yet, but would like to participate, email me and let me know! Without further ado….here’s Christopher Lirette…

“The Libertine Adventures of Scott and Jean, or Genocidal Orgasm and Mystical Unions in the Dark Phoenix Saga”

Over the last few weeks, my students and I read Chris Claremont and John Byrne’s 1980 Marvel comics classic “Dark Phoenix Saga,” the most popular story in Uncanny X-Men. I’m teaching a class focusing on superheroines and depictions of women kicking ass under the rubric of gender and sexuality. So far, I’ve spent a lot of time trying to teach that there’s more to studying gender in literature than pointing out moments of sexism—a harder task than I thought it would be, perhaps because our primary texts feature scantily clad women beating up villains and forming romance with dudes whose clothes get caught in their muscle striations. Although William Marston Moulton created Wonder Woman in 1942 to combat “the blood-curdling masculinity” he found plaguing titles such as Batman and Superman, it’s not until “Dark Phoenix Saga” that we get a comic book that truly addresses the problem of the deuxième sexe superheroique: a story that revels in the messiness of desire, one whose heroine’s problems, while mythic, symbolize the contradictory messages real people receive about gender.

Before the story takes place, Jean Grey, a mutant telepath known as Marvel Girl, saves the universe in an act of redemptive sacrifice. After her death, she is reborn as an incarnation of the Phoenix Force, a sort of omnipotent cosmic spirit that functions as both the creative and destructive force in Marvel’s cosmology. Another mutant, Jason Wyngarde, begins to corrupt Jean on the behalf of the Hellfire Club.

Already in these first pages where Wyngarde first appears, there’s a wealth of significant allusions. The Hellfire Club was a “real life” libertine club in 18th century England. Its members met at West Wycombe to supposedly partake in all manner of debauchery—from heresy to orgy—under the aegis “Fais ce que tu voudras” (Do what thou wilt—a famous maxim for fans of Aleister Crowley, François Rabelais, and St. Augustine). When the Hellfire Club shut its doors, a new libertine club sprung up, unsurprisingly called The Phoenix Society. These allusions carry over in the visual representation of Marvel’s Hellfire Club and its members. Their meeting locations hint of baroque European interior decorating and secret societies. Jason Wyngarde sports a mutton chop, a greatcoat, and Hessian boots. He is a straight-up dandy, and so is the leader Sebastian Shaw. The club’s most famous member, Emma Frost, wears a white corset, white panties, white thigh high boots, and a furred white cape, and despite her anachronistic ensemble, exudes the kind of dungeon decadence the original club strove for. This marriage of 18th century libertinage and a 1980s four color comic isn’t just for laughs: it forms the teeming subtext that sexualizes the Dark Phoenix tragedy.

Wyngarde’s great idea about how to defeat the X-Men wasn’t to engage them in battle, it was to slowly turn Jean, the most powerful member of the group, evil. Or at least, that’s the children’s version. What he actually says is “I’m merely giving her a taste of her innermost—forbidden—needs and desires… All I’m doing is freeing that negative part of her ‘self’ from its moral cage.” What he actually does (besides call into question the concept of the self through scare quotes) is form an illusion (it’s his mutant power to do so) that she’s on a boat in the 18th century on the way to marry Wyngarde in a pseudo-Christian ceremony at some ruins. Pretty tame for her most forbidden needs, no? But the visuals hint at some taboo sexual encounter: at her wedding, Jean dresses like Emma Frost—corset, panties, boots, cape—but all in black, and she holds a whip in her hand as the attendants, all Hellfire Club members, shout “Long reign the Black Queen.” Clearly, Jean has some fantasies of domination. Soon, this illusion replaces “reality,” and she attacks her boyfriend Scott Summers (a.k.a. Cyclops) and the rest of the X-Men, whom she sees as buccaneers and slaves. She lives the scene, goes 24/7, but unfortunately for all involved, this is no mere scene, there’s no safe word, and worst of all, this illusion whets the lust of the Phoenix.

In 1980, we knew a lot more about female desire than they did in the 1800s, when it was unspoken of and science thought a “congestion of the womb” caused hysteria, needing the manipulative hands of a doctor to “release” it lest the woman go crazy. But despite the sexual liberation of the 1960s and 70s, popular media still depicts female desire as dangerous, and the Phoenix Force is a clear metaphor for such desire. When it’s “good” it nurtures, protects, uplifts, and sacrifices for others. One might even say it’s motherly. But once it knows the possibility of erotic possibility, it’s unstoppable, absolute in its insanity and destruction. Jean immediately squashes not only the X-Men, but her new gang as well, downloading all of her godly knowledge into Wyngarde, leaving him mad and drooling. Ah, the dangers of love!

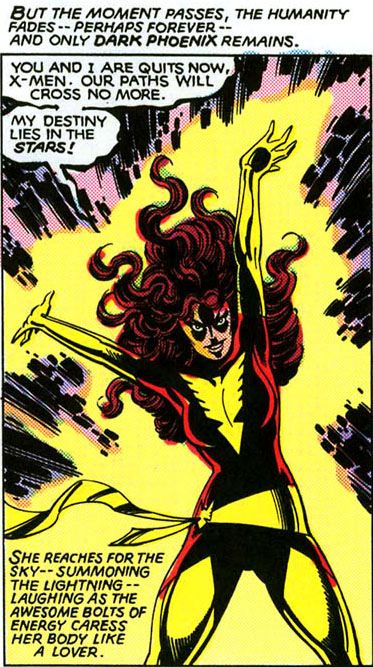

Before she flies off, Storm, the other female member of this incarnation of the X-Men, reflects that Jean is driven by “an all-consuming lust,” and Cyclops, with whom she shares a psychic rapport, senses “Jean’s enjoying this. Using her powers is turning her on—acting like the ultimate physical/emotional stimulant.” Using the language of the erotic, they are directly tying Jean’s acts of violence to her sexual urges, following a long history of matching women’s power with her sexuality, and more sinisterly, matching her sexual impulses with insanity.

And then, in her furious lust, Jean eats a star and destroys, like, 5 billion humanoid aliens.

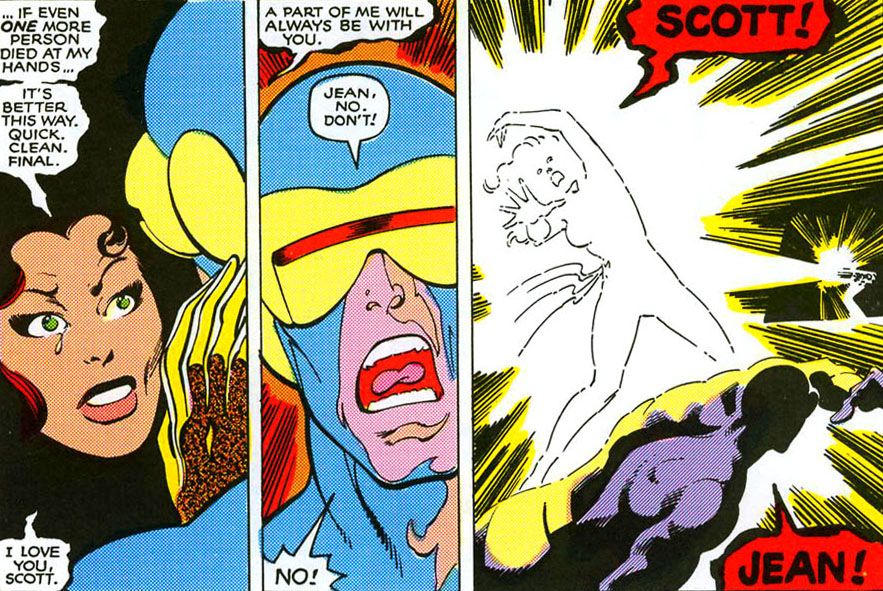

The editorial decision at Marvel was that they could not let Jean survive after that. With the help of her pre-Phoenix identity, Professor Charles Xavier, and Mr. Personification of the Destructive Power of the Male Gaze himself, Cyclops (his mutant power is that he shoots these destructive beams out of his eyes, but can’t control it—we’ll get to that in a second), Jean turns back to being a good gal. There was no way that she could be rehabilitated after such genocide, editor Jim Shooter reasoned. And so Jean, at her trial for letting her lust get out of hand, decides to kill herself for the good of all.

In the end, this tale of love and sacrifice can come off pretty conservatively in terms of sexual and gender politics. Is it necessary to have another story where a woman’s newfound sexual liberation leads to destruction or suicide? And I’m not letting Claremont and Byrne off on that point. But overall, when looking at the way that different characters perform their genders, as well as some of the other referential devices at play, the story becomes much more complicated.

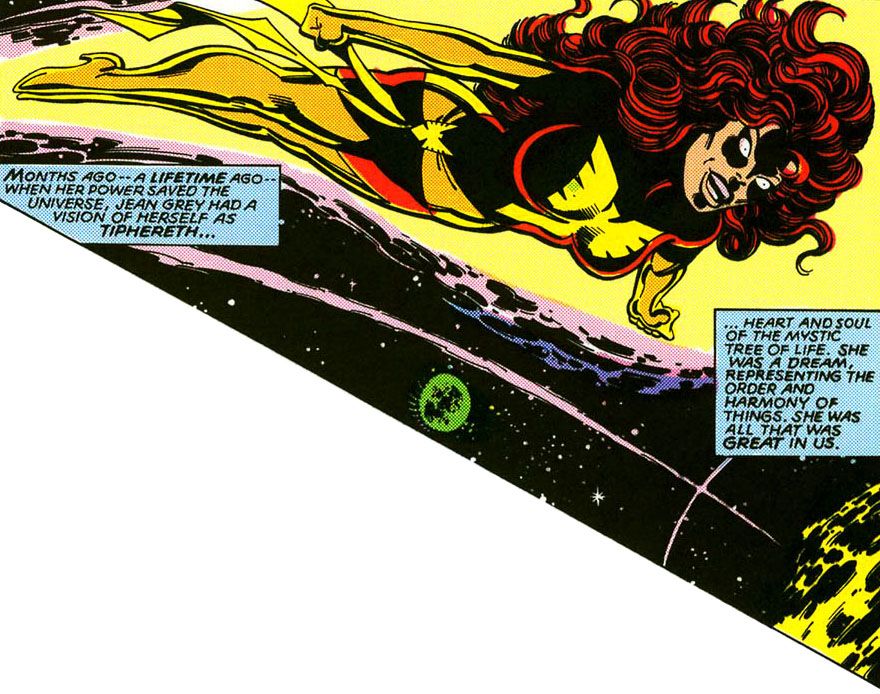

Take, for instance, that the most powerful mutant around is the sweet-natured Jean Grey, who had hitherto been seen as a love interest for several male characters (Cyclops, Angel, and Wolverine). By the end of the story arc, she holds the power of God. Many Medieval mystics, such as St. John of the Cross and St. Catherine of Siena, felt they had entered into a union with God, a particular union termed “Mystical Marriage.” Taking into account the conception of God as masculine, the mystic’s soul had to become feminine for the wedding to take place. For female mystics, this was not a problem, and femaleness essentially allows her to become filled with the god-like Phoenix Force. The male characters are so cocksure that they could never become apotheosized. Likewise, female mystics (and male ones too) were routinely ostracized, tortured, and put to death for what was perceived as erotic frenzy and theatricality. Again, we see a parallel to Jean’s plight: once empowered with the Phoenix Force, her buddies characterize her behavior as lewd and wanton.

Another possible reading would be that the world of 1980 would not have allowed true liberation. We cannot deny that with sexual liberation, a host of dangers enter the game: AIDs, other STDs, unwanted pregnancies—to say nothing of emotional issues. And not all experiments turn out for the best. Jean is able to suppress her erotic/godlike persona in the end (which may be the most impressive thing of all, to suppress a god), manipulating her friends, enemies, and technologies to kill herself. Not because she turns evil, but because the world was incapable of dealing with her as liberation incarnate, that she had become something outside the world. It’s an ultimate act of self-control, of learning from one’s mistakes, of recognizing the failings of the world around her. I think it would have been better for her to live, but it’s supposed to make her the ultimate hero, the haunting X-Men messiah, despite the unsavory insinuation that female desire is destructive. And keep in mind that Jean, more often than most comic book characters, resurrects over and over, trying out each new period in X-history.

The fact of the matter here is that sexual desire is always potentially destructive. You risk not only infecting your partner with all manner of germs, but you also risk objectifying him and reducing him to a masturbatory aid. As I alluded to earlier, Cyclops’s power is an easy metaphor for the violence of the male gaze. He cannot look at someone without protection, meaning that he cannot look into the eyes of his lovers—Jean Grey here and later Emma Frost—without killing them, leading to much chivalry, brooding, and sexual tension. At a climactic scene in Joss Whedon’s Astonishing X-Men arc, Emma Frost, a telepath like Jean who becomes one of the good guys, removes Cyclops’s inability to control his power, something Jean would do. At first, it’s presented as if he lost his power, i.e. lost his destructive virility and usefulness to the team, but then, in the biggest evolution of his character in 50 years, he controls his eye beams himself, showing that it is possible to overcome the sexist stereotypes society encourages.

And even if you don’t destroy your lover, you risk (or aim for, depending on how mystical your love life is) losing yourself in each other, dissolving the boundaries between self and self. Something that clearly happens when Jean merges with Phoenix.

Ultimately, the Dark Phoenix story arc offers a layered exploration of our own identities. Superheroes, after all, are supposed to represent us. They’re the vehicle; we’re the tenor. And though this story was written 31 years ago, the stereotypes and subversions are still relevant. Listen to Fox News or watch movies: women’s sexual desire is still considered something to fear and suppress. Movies and television shows still linger on tits and asses regardless of their relationship to the plot. And we still grow up, negotiating our own desires in a world that can’t handle them, becoming confused, sure of ourselves, and confused again. There’s a lot of this story that’s dated: the storytelling, the art, the dialogue. But it still offers a good lens with which to analyze ourselves, even if that lens is full of spandex and kaboom.

—–

Christopher Lirette, originally from Chauvin, Louisiana, lives with his wife, Linda, in Newark, New Jersey. This fall, you can read his in The Southern Review, PANK, and Hayden’s Ferry Review. In addition to writing, he has worked as an offshore roustabout, an archery instructor, and a personal chef. During the school year, he commutes to Ithaca, NY to teach courses on poetry, superheroines, and hip-hop. You can find him at twitter.com/CLImagiste

this was a really fascinating article. I loved the dark phoenix saga as a kid, but never thought of it in terms of the femme fatale’s threatening sexuality before. but it makes a lot of sense. and the comments about cyclops make me realise precisely what I didn’t like about him all this time. that’s eluded me for a while, so thank you. you’ve added a whole new line of thinking to one of my favourite x-men storylines.

Wasn’t there also a lot of post-Claremont retconning of this story further down the line that created ambiguity for readers regarding whether the Dark Phoenix influenced Jean, or was an independent occupying force whose actions Jean had no control over (because she couldn’t be revived down the line if she was TRULY responsible for genocide, etc.)? I feel like that metatext about the various creative regimes’ anxieties about the distinction between Jean and the Dark Phoenix, agency, responsibility and liminality of identity all contribute to this argument.

They retconned it (either in an issue of X-Men written by Claremont did it or in the X-Factor comic, which I think Louise Simonson wrote) so Jean and Phoenix were two entirely different characters (so that they could bring Jean back to life after they killed off Phoenix). So instead of dying, Jean ended up in suspended animation in a cocoon in the ocean or something. While the Phoenix took on her appearance, personality, and memories after Jean’s alleged death while the Phoenix also thought she was Jean. That whole thing sort of ruined “the saga” since for the people reading the comics when they came out, Phoenix WAS Jean and she actually died rather than some separate Godlike entity. But now if people read the comics, they do so with the knowledge that Phoenix and Jean are different characters and Phoenix’s death is far less emotionally resonating because of it.

Jean is dead again now and it’s been a while since that happened (near the end of Grant Morrison’s run on New X-Men) but I’m positive she’ll be back eventually. It probably isn’t a priority since Emma Frost has has taken the role of Cyclops’ girlfriend since the end of that run. Morrison also killed off Magneto (he seems to like killing off significant characters), but they “brought him back to life” shortly after Morrison was finished with his run. Something to do with how “the Magneto” who was killed was an impostor. I don’t think I read the issue where it was explained and he came back. Also, Morrison created a great character (Xorn) for his run who Magneto was masquerading as. And Marvel also brought that character back “to life” although he never actually existed in the first place. Something to do with the non-existent character’s brother taking up the mantle and having the same powers. It’s all pretty stupid.

Claremont was also unhappy with how one of Jean’s comebacks compromised Cyclops as well as his Madeleine Pryor character, right? I should emphasize I only know all of this from having gotten caught and wasted hours in several X Men-related wikipedia loops, not from ever having actually read the comics (although at a co-worker’s recommendation, I started to read Morrison’s run on my ipad, but never finished). I’ve been a soap fan for years, this is the same shit but with powers.

Not sure. I think Madelyne Pryor was “created” by Claremont. She looked identical to Jean and Cyclops married her. Later, it turned out she was Jean’s clone. Don’t know whose stupid idea that was. Probably Scott Lobdell’s or an editor’s. I think Stryfe cloned her, who I’m pretty sure was a clone of Cable himself. This stuff is ridiculous. I think they killed her off after making her evil or something in the big “Inferno” event that Marvel did like forever ago.

Then there was that whole “clone saga” in Spider-Man. I only read the first issue of that. It was controversial because people thought it sucked. Although they did a “cover” version of the story in the Ultimate Spider-Man title (which I did read), and it was very good. Morrison’s run is definitely worth finishing. I read Claremont’s stuff when I was like in elementary school and junior high. The comics he co-wrote with John Byrne were much better than the ones that he later wrote himself (which was when I started reading them). Seems like he sort of went insane. I’ve been reading the Essential X-Men collections over the years for the sake of nostalgia. I think there’s one more volume left to be published before Scott Lobdell takes over the writing. That’s when I stopped reading it, even though I didn’t pay attention to who wrote what. I just noticed a distinct change in the quality.

Not sure. I think Madelyne Pryor was “created” by Claremont. She looked identical to Jean and Cyclops married her. Later, it turned out she was Jean’s clone. Don’t know whose stupid idea that was. Probably Scott Lobdell’s or an editor’s. I think Stryfe cloned her, who I’m pretty sure was a clone of Cable himself (who I think was either the son of either Cyclops and Madelyne Pryor or Cyclops and Jean Grey and an old guy from the future). This stuff is ridiculous. I think they killed her off after making her evil or something in the big “Inferno” event that Marvel did like forever ago.

Then there was that whole “clone saga” in Spider-Man. I only read the first issue of that. It was controversial because people thought it sucked. Although they did a “cover” version of the story in the Ultimate Spider-Man title (which I did read), and it was very good.

Morrison’s run on New X-Men is definitely worth finishing. I read Claremont’s stuff when I was like in elementary school and junior high. The comics he co-wrote with John Byrne were much better than the ones that he later wrote himself (which was when I started reading them). Seems like he sort of went insane. I’ve been reading the Essential X-Men collections over the years for the sake of nostalgia. I think there’s one more volume left to be published before Scott Lobdell takes over the writing. That’s when I stopped reading it, even though I didn’t pay attention to who wrote what. I just noticed a distinct change in the quality.

Christopher Higgs is HTML Giant. Great article, Chris.

[…] The Libertine Adventures of Scott and Jean, or Genocidal Orgasm and Mystical Unions in the Dark Phoe… […]

[…] Remember the Dark Phoenix Saga? Yeah? HTMLGIANT too […]

[…] years ago, when I read the Dark Phoenix Saga in the X-Men, I totally missed the pretty remarkable subtext that, quite frankly, seems to obvious to have been wholly […]