Random

Transgressive Circulation: Alireza Taheri Araghi and “Younger Iranian Poets”

1.

In my last post, I wrote that I see a lot of anxiety about translations in US literary discussions: “… the threat of translation is the threat of a kind of excess: too many versions of too many texts by too many authors from too many lineages.” Once you add the writing form another country, the illusion of objectivity of a single “tradition” is put in doubt (of course this dynamic is often at play in smaller, non-major countries).

One way this anxiety is manifested is in the skepticism about foreign texts. Whenever there’s a translation, people wonder: Is this really a major writer? Does this writer really deserve to be translated into our language? Is this translation really correct or is it corrupting the truly great poet? Or, as I noted in the essay I linked to last post, are the “young American poets” being “improperly influenced” by foreign writers without having mastered their tradition.

2.

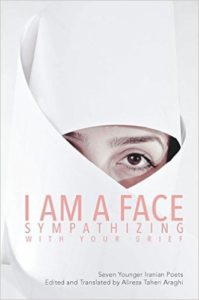

In his anthology “I Am A Face Sympathizing With Your Grief,” Alireza Taheri Araghi shows no intention of creating an illusory alternative canon of great works of Iran. Instead he has searched out underground poets – or more correctly, Internet poets – who have not been deemed publishable by the Iranian government. In a sense Araghi has done the opposite of the typical canonical anthology; he has chosen “young” poets who excite him, many who have little or none of the official recognition that translation discourse tends to demand.

This anthology is one of a great, important book of poetry in part because it eschews “importance” and stature, and in part because it consists of poets from Iran (obviously a country demonized by many in the US). But mostly it’s a great book of very contemporary-seeming poems, including a series of poems writing through Quentin Tarantino’s Killl Bill, plenty of strangely stoic, darkly humorous poems about war, and this brutal poem called (in translation) “Shitkilling” by Arash Allahverdi:

come

come and do drugs

bring the drugs and do it

drink

drink the water

as if semen drink the waterdrink and piss

piss on the office ceramic tiles

don’t tell your colleague you pissed

tell him this is orange juice

your colleague will cheer up

and say real friends share drinks

and there are consequences

but don’t worry

tell lies

sleep

take lorazepam and sleep in the office

think of hips in your sleep

think of the capacities of hips…

[Read the rest in Asymptote.]

And this vast poem by Mahnaz Yousefi that starts off addressing the tumultuous city of Rasht but ends up in the politically charged bodies of women:

…

my dearest Rasht!

with that ilk of yours sucking off the breast

with the drinking struggle in the mouth

with a couple of glasses of milk after the suicide pills

we roamed through your pharmacies night and day

and every time we were out of antidepressants

we took to contraceptives

and every time we were done

we were pregnant

we are afraid of postpartum depression

you tell us you tell us what to do what to do with the orphanage we have in our wombs

you tell us you tell us what to do with the blood clots clots

boy’s bulging arms

girl’s full breasts

and bits and bits of fetus pouring out of your threshold

who were home alone?

who was hugging their knees

crying into the cuffs of their sleeve?…

And the subversive, almost Stephen-Crane-like allegories (often about war) like this one by Ali Akhavan (also translated by Alireza):

… “Ah,” loudly he said and

ended with a narrow smile

like Indians,

“Goodbye my friend

Goodbye”

and then

died

and then I

tried to

throw some dirt

on my dead lion’s body

tried to

keep a fire alight

for a little while

tried to plant a few flowers

but

there was no fire

there was no flower

and no dirt

there was nothing there

because my lion

was dead.

3.

In other words, Araghi has produced a horrific book of translation that embraces all the things we are supposed to reject about translation: he’s deliberately not compiled an accepted canonical book, which we can then quarantine off as another instance of a “national literature.” Instead he’s created an incredibly powerful book of contemporary poetry that I think will affect a lot of American readers (and readers from elsewhere!). National literature anthologies (or “World Lit”) tend to give an impression of poetry as static, stable, masterable. Instead of this restricted economy of literature, Araghi gives as a vision of Iranian poetry in motion: a transgressive, volatile, feverish book.

Tags: Alireza Taheri Araghi, Arash Allahverdi, Mahnaz Yousefi

i found your cordite essay interesting

i once had the idea to feed foreign poems into web translators then transliterate the results into whatever seemed approriate to me

i could probably submit them as original works without getting pinged for plagiarism

or i could announce my technique and call it conceptual writing

but the question of the relationship between the product and the original would still be there for anyone who cared to ask

to the point of the pollution of usa poets

i cant imagine how anyone could be worried foreign poetry would be more damaging than whatever local media products a poet might enounter whilst pursuing mastery of a supposed tradition

in other words are students ideally to be sequestered until granted release by the graduate board

or is the ability to retain purely american values despite the onslaught of additional media part of the test

cool stuff

i wish there were more translated works

i don’t understand why anyone would have a problem with translations

freeing writing to a broader readership