The House with a Clock in Its Walls

The House with a Clock in Its Walls

by John Bellairs

Dell Publishing, 1973

179 pages / buy at Powell’s

- I first read this novel when I was a kid, checking it out from the library. Actually, I first read John Bellairs’s novel The Treasure of Alpheus Winterborn (1978), which I picked it up because of its Gorey cover and illustrations. And it’s through these novels, I think, that I first learned about Edward Gorey.

- I got my current copy of THwaCiIW from my friend Rebekah, last November, at her Friendsgiving party. And it’s only appropriate that Rebekah should have given me a horror novel, because my nickname for her is “Ghost Mouth.” (Thanks, Ghost Mouth!)

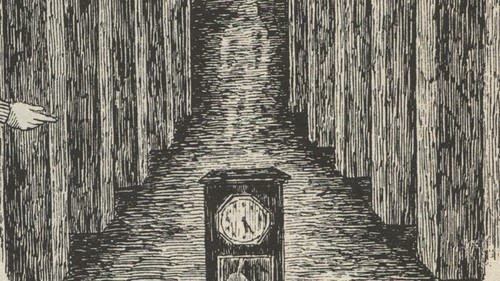

- THwaCiIW is a Gothic horror novel for kids, and it’s genuinely spooky. For one thing, it’s about a house with a goddamned clock in its walls! And not just any clock, but a doomsday clock that, when it goes off, will bring about the end of the world. The book’s protagonist, Lewis Barnavelt, along with his Uncle Jonathan, can hear the clock ticking all throughout their house, but they cannot find it. (The evil wizard who made and hid the clock cast a spell that causes the clock’s ticking to sound the same from inside every wall). And so neither the heroes nor the reader know when the clock will go off and cause the world to end. Which is like . . . Christ!

- The whole novel is tremendously suspenseful. Rereading it now, I still wanted to zip through to find out what would happen.

- I remember that, as a kid, the book scared the crap out of me. I found it frightening even now, reading it as an adult. I mean—it’s about a house with a goddamned doomsday clock hidden in its walls!

- Receiving and rereading the book prompted me to check out the John Bellairs website, Bellairsia, which is fun and informative, including providing other other things reading guides for young and old readers alike. (Here’s the page for THwaCiIW.)

- THwaCiIW has, over the years, borne a succession of different covers, many of which are nice. But only one of them was done by the one and only Edward Gorey (the cover pictured above).

- Regardless of which cover adorns it, the novel was illustrated by Gorey. This was Gorey’s first collaboration with John Bellairs, and he went on to illustrate several other of the man’s books: The Curse of the Blue Figurine (1983); The Mummy, the Will, and the Crypt (1983); The Dark Secret of Weatherend (1984); The Spell of the Sorcerer’s Skull (1984); The Revenge of the Wizard’s Ghost (1985); The Eyes of the Killer Robot (1986); The Lamp from the Warlock’s Tomb (1988); The Trolley to Yesterday (1989); The Chessmen of Doom (1989); The Secret of the Underground Room (1990); and The Mansion in the Mist (1992).

- I would be remiss if I didn’t mention this website, which lists various books with covers and illustrations by Gorey. Note however that the site is not complete, as it fails to include Donald Barthelme’s Come Back, Dr. Caligari, and Alexander Theroux’s The Lollipop Trollops and Other Poems (which is to my knowledge the only Dalkey Archive Press book to feature work by Gorey).

- This post could easily turn into a “25 Points: Edward Gorey,” and I’ve been meaning for some time to write about that artist, and how his work has largely been misunderstood, and perhaps even ruined. But that dismal study will have to wait for another moody, rainy day.

- Returning our attention to John Bellairs: he was the author of over a dozen books for children, most of them of the Gothic persuasion. He studied English and Catholicism at Notre Dame and the University of Chicago, then turned to writing fantasy after reading The Lord of the Rings.

- I was thinking that I should write the man a fan letter, but he died in 1991. (I suppose I could still write him a letter; perhaps his ghost would care to read it?)

- Bellairs wrote two sequels to THwaCiIW: The Figure in the Shadows (1975) and The Letter, The Witch, and The Ring (1976). Since Bellairs’s death, another author, Brad Strickland, has continued the series, and some of his books feature illustrations by Gorey. I haven’t read any of these installments, although I intend to check them out. (Eventually.)

- Bellairs’s writing, overall, can only be described as idiosyncratic. For one thing, he set THwaCiIW in 1948, a maneuver I find curious. I’m not sure what doing that really accomplished. While reading I kept forgetting that detail, assuming that the action was set in the 1970s.

- I also must voice some quibbles with some of Mr. Bellairs’s aesthetic decisions. For instance, he’s occasionally lazy about POV, needlessly shifting from Lewis (the protagonist) to his Uncle Jonathan. At other times, the POV drifts into a needless second person address (although a lot of children’s books tend to do that, and I have always wondered why). Furthermore, a few aspects of the book haven’t aged particularly well—such as the subplot involving Lewis’s friend Tarby, which feels kinda creaky. . . . The book is, as a whole, rather leisurely paced, perhaps even a little rambly . . . but as a consequence, it’s also not wholly plot-driven, which I think pleasant.

- Here’s a real “Problem,” though. The book opens with Lewis’s parents dying in a car crash, which is what causes him to go live with his Uncle Jonathan. Lewis initially seems upset about this: he frets over whether he will get along with his uncle, and he chokes up when he remembers his mom and dad:

“Yes, but my dad won’t . . .” He stopped. Jonathan saw tears in his eyes. [There’s one of those needless POV shifts.] Lewis choked down a sob and went on, “My . . . dad wouldn’t have let me play for money.” [They’re playing poker; Uncle Jonathan lets Lewis do all sorts of fun grown-up things.]

- [cont’d] But, once the first chapter ends, Lewis forgets his parents entirely—which is odd, given that he’s depicted (as you can see from this passage) as a fairly sensitive kid. And one of Bellairs’s strengths as a writer lies in crafting complex psychological portraits of his characters. But opportunities to have Lewis remember his parents later pass without comment. For instance, there’s a tense car chase scene, midway through the book, but that never once prompts Lewis to think about his parents, who of course died in a car crash. The impression is that Bellairs, having killed off Lewis’s parents, completely forgot them. (It’s not unlike when Christie Malry’s mother dies.)

- Another missed opportunity: Lewis at one point resurrects a dead person, which is great (and by “great” I mean “fucking awesome”), but he never once even thinks about resurrecting his dead parents, which—well, isn’t that damned peculiar? Instead, he accidentally resurrects one of his uncle’s greatest foes—which feels somewhat contrived/clunky.

- God, I’m being way too harsh. These inconsistencies, peculiar though they may be, also lend the novel an odd, forgetful quality. (It’s not unlike Lewis’s Uncle Jonathan.) From what I’ve read online, Bellairs originally wrote the novel as an adult mystery, and was persuaded by his editor to revise it into a young adult title—and if that’s true, then I imagine that accounts for these lapses, and the casual construction of Lewis’s callousness.

- OK, one more complaint: the novel’s two bad guys ultimately turn out to be ciphers, being evil magicians who are just evil for the sake of being evil. Although to be fair, they’re also terrifyingly evil. But in all honesty, I found it slightly disappointing that the novel’s sympathy and complexity didn’t extend to them.

- But these are all minor criticisms. Bellairs’s writing, taken as a whole, is so damned eccentric that what might be serious flaws in another book largely make this book feel that much stranger.

- It helps that the whole book is delightfully weird. Bellairs had a genuine interest in the occult, and depicts some genuinely magical things, like a marvelous scene where Uncle Jonathan eclipses the moon. And The novel also refers freely to John Dee, John Stoddard, and the hand of glory, all of which might lead a kid (or an adult) to want to do some research. (What’s more, the source of the hand of glory is deliciously gruesome.)

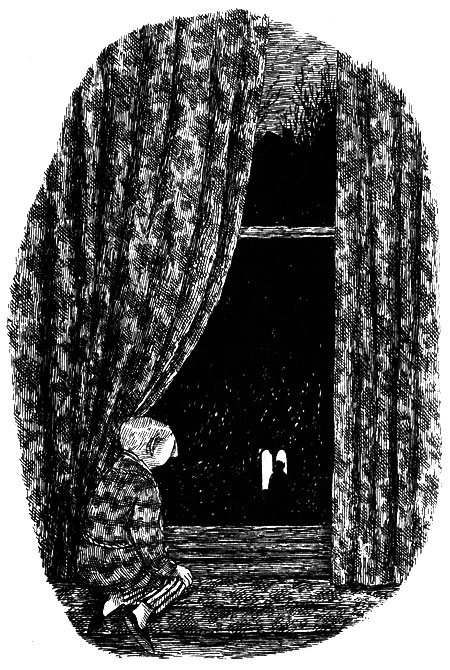

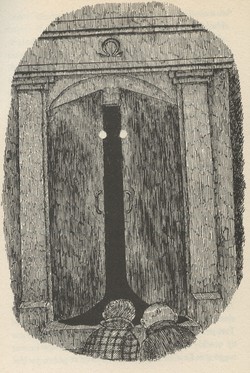

- As stated, the book is pretty scary. One of the spookier elements is its burning eyes motif: Lewis often feels the evil wizards staring at him (which is reinforced by several of the illustrations—see below). This aspect of the novel plays out very nicely, and might help teach younger readers how to recognize motifs.

- The writing is always amiable and good-natured. Bellairs clearly enjoys the subject matter and his characters, and his passion for the material shines through. He also never writes down to his audience.

- The novel’s tone reminds me of a more sober—or perhaps less self-conscious & more ambivalent—Daniel Manus Pinkwater, in particular his books like Lizard Music and Alan Mendelsohn, the Boy from Mars (both of which I greatly admire).

- THwaCiIW was never made into a movie, although 1979 saw an episode of the series “CBS Library,” “Once Upon a Midnight Dreary,” in which Vincent Price narrates an abridged version of it. I’ve read a review here or there that suggest the program was awful. There are, unsurprisingly, plans afoot now to make it into movie, but “details are only available on IMDB Pro.” I can only hope the end result is even half as good as The House with a Clock in Its Walls.

Tags: 25 Points, Alexander Theroux, Brad Strickland, Daniel Manus Pinkwater, donald barthelme, Edward Gorey, hand of glory, John Bellairs, John Dee, John Stoddard, The House with a Clock in Its Walls, Vincent Price

I haven’t read the book, but it does strike me that the kid not missing his parents is pretty typical of juvenile lit generally. It’s probably a hallmark of the field that such stories have at least some degree of empowerment fantasy for the intended reader, so that juvenile characters almost never miss their parents or any other authority figures for the same reason most kids fantasize at least once about running away or finding out they were adopted and they owe little to their “parents”.

Even in a story where the young hero has parents, they’re likely to be invisible, indistinct characters not unlike the “Warwrwarwrwarw”-ing adults in an old Peanuts TV special–after all, if they were responsible parents and active in their kids’ lives, how likely is it they’d allow their children to explore a mysterious abandoned house, ride their bikes all over town doing amateur detective work, spend the summer with a crazy old professor in the country (even if London is being bombed), pilot an experimental atomic submarine, roam the dark mysterious woods etc.?

If the kid misses his parents, or is really dependent on them, there’s less of a story (or at least there’s a different kind of story). The fantasy in these stories is that kids are capable, responsible, effective, and effectively immune from the very worst things that could happen to a kid in a cruel hard world. So it isn’t really odd if they don’t think of their parents while they’re solving a crime or saving the magical kingdom or whatever they’re doing. Indeed, it’s even convenient to the story if their parents are dead, since it saves the kids the trouble of worrying about what mom might think about some of the insane chances they’re taking.

The Vincent Price thing was exceptionally scary when I saw it in 1st grade. Bellars had another book that freaked me out even more than THWTCIIW, THE EYES OF THE KILLER ROBOT. Just looked it up, and the moment that always stuck with me was excerpted on the “Bellarsia” website.

http://www.bellairsia.com/the_work/eyeskr/index.html

EXCERPT

Not far from the back door of the house stood a bench covered with

peeling white paint. It was a garden seat, the kind people used to make

so they could sit outdoors on hot summer nights. The bench stood in a

patch of wild rosebushes not far from the rugged wall of the mountain,

which towered overhead. A man was sitting on the bench — a man Johnny

had never seen before. He wore baggy, dusty overalls and a faded plaid

shirt, and he had a big mop of straw-colored hair. The bunch of pieweed

stalks fell from his numb fingers, and he took a couple of shuffling

steps forward. And then, as Johnny watched, the man stood up. He took

his hands away from his face and he stumbled. Johnny gasped in terror —

the man had no eyes. Streaks of blood ran down from empty black

sockets.

“They took my eyes,” the man moaned. “They took my eyes.”

Johnny opened and closed his mouth, and made little whimpering noises.

He shut his eyes tight to block out this horrible vision, and when he

opened them again a second later, the man was gone.

I loved Bellairs as a kid. Pretty sure I read all of his books you mention here. I remember toward the end feeling like I was outgrowing them and feeling frustrated with the Christian aspects which seemed heavy-handed in some of the books.

I read this for the first an only time a couple of years ago when when I only read children’s book for about a year. Protagonists in kids books are often orphans so they can go off and have adventures without their parents being viewed as negligent. Either their guardians are kooky or they’re terrible people.

Yeah, I get that it’s a convention of the genre. What makes it odd here, though, is that there are two different scenes during which Lewis remembers his parents, and cries. Then the rest of the time he forgets about them. So I guess what I’m “complaining” about aren’t the scenes where he forgets his parents, but the scenes when he remembers them (inasmuch as I’m even complaining, mind you—more like I’m pointing out an odd feature of the text).

Yeah, it’s an old convention; I just read Oliver Twist. Again, I don’t mind the convention, and I get why authors use it. What seems off here though is the fact that Lewis specifically does think about his parents sometimes, and misses them. Then the rest of the time he forgets them. It’s that discrepancy that (necessarily?) makes him, and the writing, seem somewhat schizophrenic.

I’m not really complaining about this, mind you. But it stood out to me this time, and it does seem some kind of discrepancy or inconsistency or something.

Most honestly, it reads to me like the result of a lack of revision. Supposedly Bellairs originally wrote the book as adult fantasy, then revised it to be YA on the advice of his editor. And my guess is he threw in the car crash / orphan-making angle precisely because it is a convention of the genre. Then he maybe threw in a scene or two where Lewis gets sniffly over it. And that was it; he didn’t take it any further.

That’s my guess. But, again, I don’t think it ruins the book, really. It just stands out.

Bellairs was a scholar of Christianity, apparently. I don’t know if he himself was Christian, though?

I suppose that’s what bothered me about the villains in this being so one-note. I got the impression that, at the end of the day, despite all the other odd aspects of the book, Bellairs was embracing just as Manichean a notion of “good” vs. “evil” as, say, George Lucas. Which is disappointing. (And Darth Vader’s really more complex than the evil duo in this book, who just want to bring about the end of the world because evil.)

But Bellairs’s villains sure get points for style. Darth Vader never constructed a doomsday clock and hid it inside a house’s walls and enchanted the thing so that its ticking could be heard equally loudly behind every wall in the house.

I REMEMBER READING THAT ONE!

Above all my main point is that John Bellairs books should be handed out like candy to every child in the realm.

“Once Upon a Midnight Dreary” is on Youtube,

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nNnJHHK5Qdc&feature=player_detailpage#t=1361

Thank you!