Good Offices

Good Offices

by Evelio Rosero

Trans. by Anne McLean & Anna Milsom

New Directions, 2011

144 pages / $13.95 Buy from New Directions or Amazon

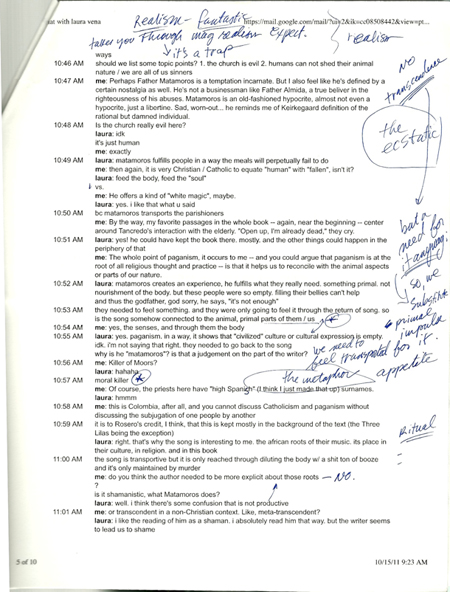

In September of 2011, my colleague Laura Vena and I decided that we were both sufficiently interested in Evelio Rosero’s Good Offices to attempt a “collaborative review” of the novel. (As something of a student of the novel-as-form, I was intrigued by Good Offices‘ superficial resemblance to Lewis’ atypical Gothic The Monk. Laura, though she will probably raise a protest, is an expert in Latin American literature.) Laura and I ultimately agreed that our collaboration would take the form of a conversation about the book, which we each read yet refrained from discussing prior to our officially meeting. Presented here is as full, complete and accurate a record of our conversation as Google’s transcription of our live chat will allow. What it lacks in context and gracefulness I trust it makes up for in spiritedness and candor. In fact, reading over these exchanges again, I appreciate how they allow me to eavesdrop on those selves taking turns speaking up—can I really say that they speak through me?—when I talk about books. Or: when I am retelling yet again those fictions by virtue of which we can even discuss the notion of fiction. (JM)

A word about tone: due to the candid nature of IM conversations, much of the following text is raw in character. My initial impulse was to edit out all my informal language, which reflects not my intellectual self, but the manner in which I engage in impassioned conversation with friends… Not necessarily for mass consumption. But in discussions with Joe, we ultimately felt we should maintain the tone of the original conversation to keep true to the experiment of long-distance collaboration that resulted in this review. For better or worse. (LV)

***

JM: yeah, so, I’m curious… what is your overall impression of this book?

LV: in what respect: as in do i think it’s a strong work or what kind of work is it? what’s it doing that’s interesting to us? what’s it failing at? what’s it failing at well and at what poorly?

JM: any of the above, really. I have to say I exited this book with a feeling of vague disappointment, vague as in both “ill-defined” and “of indeterminate origin.”

LV: to me it failed at this: some of the more interesting aspects that were begun early on dropped off. gone. vanished.

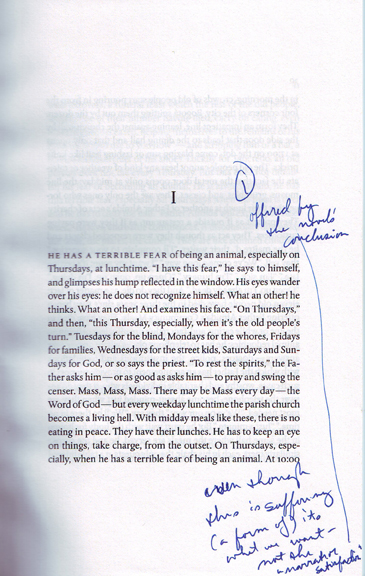

JM: yes, the opening paragraphs are very strong. “He has a terrible fear of being an animal…” Not, “feeling like a animal”, no shelter offered by similes or analogies here. But the brute fact: he (it turns out “he” is the hunchback / glorified altar boy Tancredo), like all human beings, is an animal, or of animal nature.

The irony being: fear is a very animal emotion, here recast at the utmost in rationality.

LV: for me, it starts like a modern fairy tale almost. beauty and the beast. except the beast is overcome (poisoned by / captive to) his humanity, and the object of his lust (or the director of it) is a seemingly madonna-esque (as in the virgin, not the one like a virgin) the sinner, she’s the beast

i’m very disappointed in the stereotypical latino portrayal of women here: the spoiled virgin, the old witches, all the old fucking tropes in which women are caricatures.

i like what you say, though, about the animal parts of us, or really, to be human is to be animal

JM: Sabina is a potentially fascinating character who ultimately only sings one note. There’s something both spectral and carnal about her, but not in an overtly Gothic way (she’s not a revenant, or a succubus), but Rosero does little to develop her relationship with her own sexual urges

LV: yes, yes. beautiful

and of course, he throws in that her godfather raped her

so, she’s a victim of sexuality, not a master of it

those first paragraphs are the best in the book

JM: true, but that kind of psychological “backstorying” always feels cheap and soap opera-ish to me

LV: yes. that’s what i mean—cheap and disappointing and fucking typical. it’s like the female equivalent of a fictive castration

JM: I agree… and I think those first paragraphs contribute far more than any of explicitly / intentionally satirical portions of the novel to articulating an original point-of-view on organized religion. But I was not as aware or bothered by the apparent stereotypes, in part, because this is a fantastical grotesquerie

LV: that’s a really great categorization for this, and defining it that way almost makes it better… except that it still disappoints.

i found the characterization of women terribly annoying

of course, we see more in the minds of the men

not just tancredo

JM: it is a man’s world, which may be part of the critique rosero is leveling at this world

LV: men are “of the brain” even if they’re worrying about becoming animals. even the cantor, singing priest, so of the body / bottle, seems to channel some mystic brilliance, seems to deliver. but of course, that character to me seems to embody temptation. maybe i can’t have that both ways

JM: Perhaps Father Matamoros is a temptation incarnate. But I also feel like he’s defined by a certain nostalgia as well. He’s not a businessman like Father Almida, a true believer in the righteousness of his abuses. Matamoros is an old-fashioned hypocrite, almost not even a hypocrite, just a libertine. Sad, worn-out… he reminds me of Keirkegaard’s definition of the rational but damned individual.

Is the church really evil here?

LV: idk

it’s just human. no transcendence is really possible, but there’s a need for it anyway. so, we substitute a primal impulse. we need to feel transported.

JM: exactly

LV: matamoros fulfills people in a way the meals (provided by the church to the hungry) will perpetually fail to do

JM: then again, it is very Christian / Catholic to equate “human” with “fallen”, isn’t it?

Matamoros offers a kind of “white magic”, maybe.

LV: yes. i like that—what u said

bc matamoros transports the parishioners

JM: By the way, my favorite passages in the whole book — again, near the beginning — center around Tancredo’s interaction with the elderly at those meals he dreads. “Open up, I’m already dead,” they cry.

LV: yes! he could have kept the book there. mostly. and the other things could happen in the periphery of that

JM: The whole point of paganism, it occurs to me — and you could argue that paganism is at the root of all religious thought and practice — is that it helps us to reconcile with the animal aspects or parts of our nature.

LV: matamoros creates an experience, he fulfills what they really need. something primal. not nourishment of the body. but these people were so empty. filling their bellies can’t help

and thus the godfather, god sorry, he says, “it’s not enough”

they needed to feel something. and they were only going to feel it through the return of song. so is the song somehow connected to the animal, primal parts of them / us

JM: yes, the senses, and through them the body

LV: yes. paganism. in a way, it shows that “civilized” culture or cultural expression is empty. idk. i’m not saying that right. they needed to go back to the song

why is he “matamoros”? is that a judgement on the part of the writer?

JM: Killer of Moors?

LV: hahaha

“moral killer”

JM: Of course, the priests here have “high Spanish” (I think I just made that up) surnames.

LV: hmmm

JM: this is Colombia, after all, and you cannot discuss Catholicism and paganism without discussing the subjugation of one people by another

it is to Rosero’s credit, I think, that this is kept mostly in the background of the text (the Three Lilas being the exception)

LV: right. that’s why the song is interesting to me. the african roots of their music. its place in their culture, in religion. and in this book

the song is transportive but it is only reached through diluting the body w/ a shit-ton of booze and it’s only maintained by murder

JM: do you think the author needed to be more explicit about those roots?

LV: no. well. i think there’s some confusion that is not productive

JM: is it shamanistic, what Matamoros does? or transcendent in a non-Christian context. Like, meta-transcendent?

LV: i like the reading of him as a shaman. i absolutely read him that way. but the writer seems to lead us to shame

i don’t know that we needed to see the other priest dead, etc.

JM: do you think GOOD OFFICES is a case of a book that goes too far into allegory?

LV: yes

well put

do you?

it’s overwrought w/ it

JM: you know i have strong reservations about allegory

and I feel its presence here, though not always

LV: and what worked in the beginning as i look at it is its animal-ness

JM: or consistently

LV: i mean, it’s so obsessed with the moment

and then it moves away from the experience of the moment into some kind of moral hell

JM: yes, but I think it also has a strong critique to offer to anyone who would romanticize “native life before the Spaniards”

LV: the beginning i mean is obsessed w/ the moment

possibly. not overtly though

JM: its urgent in the best way, that opening

LV: yes, “especially on thursdays at lunchtime”

JM: I don’t know… there is something truly awful about the Llilias opting for revenge

LV: yes. i agree w/ you. it turns them into caricatures

i think it does. work against it an a most specific way

JM: i think that, as a reader, i most object to allegory not because it is didactic, but because it requires me to betray my attention to the text, if that makes any sense

LV: god it’s a revelation to me. maybe this is part of why you dislike allegory. it tries so hard to not be in the moment

anyway

i think this text is split.

divided into 2 parts

JM: how so? where does it bifurcate? and shouldn’t we expect some sort of tripartite breakage here? or am I being corny?

JM: yeah, but I don’t want conventionally “realist” texts either

LV: no. of course

JM: yes, the text, like the New World itself (thanks, Cortazar!) is this very fraught combination (I want a stronger word, though) of distinct cultures

LV: convergence? collision (my fav)

JM: but — back to allegory for a second — I think of Bunuel, and how he can, in a film like The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, suggest “deeper meaning” through very specific and concrete images, actions. Not just allusive names and exposition.

LV: you know what? is it partly disappointing bc no one seems to be steady here. i mean i don’t know who the fuck any of these people are. i think tancredo is the closest to a non-sketch of a character, but he seems to fade. they all fade. only the lilia’s actions and power persist. and they are not individuals. they are a coven (a group of 12 / 13 with friends; i forget)

i wrote that as you wrote yours and i think they can be related. who’s concrete here

JM: and all this could work if the text were a bit more self-conscious of itself

LV: yes

the animal in “us” gets fed by, superseded by, etc. the metaphysical

i mean how the fuck is that working

i’m confused

JM: oh, the terror of metaphysics

LV: haha. but i don’t think there’s really a difference between the animal and the metaphysical…?

JM: how so?

LV: if we are talking metaphysical in terms of supernatural, in the world of this book, “magic” or mystic things happen only to satisfy our animal natures. I think the book in a way subverts the seeming contradiction of the terms. The metaphysical is driven by something beastly.

JM: metaphysics are especially terrible / awful / predatory (maybe?) when mixed-up with morality / moralism

I wish Tancredo were a bit more cognizant of the various narratives which he is, at times, helplessly enacting (and you get a bit of that in his interactions with the Church’s Blessed Telephone), or if Matamoros were a bit more sinister

or, better yet, if everyone in the book were complete ciphers

LV: the power of the lilias is the slave of their fucking need to satisfy their cavernous hunger (they lost everything; the govt killed their families, they lost their homes) and their act of rebellion is fuelled by their righteous indignation ( their “saviors” worked them to the bone; they were enslaved). and so they kill them. just another representation of the truth that saves. this is the allegory: to express power in a misogynistic society, women have to become “evil.”

yes to your point—Tancredo’s not solid enough somehow. starts off so well

JM: But Catholicism never promises anything but suffering on the way to salvation

LV: there is political commentary in the lilias and their reversal

JM: Pick up your cross, Laura

LV: haha

damn. he really packed too much in a little text

the history of race, domination, and genocide in columbia

JM: Yes, I don’t know how much of an issue Rosero takes with Catholic doctrine per se as opposed to “The Church” (never that monolithic, of course)

LV: you know what? that’s a good point

i still feel that he was somehow portraying all that transpired as “sin”

JM: I can’t read this book except through my own experience growing up Catholic, and in a very conservative, pre-Reformed-feeling church

Well, the ending is anything but happy

LV: yes. but the lillias are happy

JM: Matamoros being carried away as a sort of sacrificial figure

LV: haha

he is going to become their slave

JM: how so?

LV: i can’t imagine that they aren’t going to keep him alive. the lilias are now presiding. Matamoros has no authority.

JM: i suppose. just because a figure is sacred, that does not invest it with any power. it just removes that figure from the regualr flow of power. you do get that sense, though, right, that Matamoros is in danger?

LV: it reminds me of a roman polanski film

yes

JM: more blood is going to be spilled

LV: they even fatten him up like hansel and gretel

JM: and no ideas, however beautiful, ever excuse that

LV: right.

JM: So… Is GOOD OFFICES an allegory? It is part of a “magical realist” tradition in which allegory, and the breakdown of allegory, is a critical concern? I hate that all Latin American lit has to be read through the lens of magical realism

LV: yes. the language is so NOT magical realism. in fact, i half thought it was a failure bc it tried to hard to be anti-m.r.

me too. but if the shoe is meant to not fit…

JM: if this novel is a critique, is Rosero’s issue with specific aspects of Catholic doctrine per se or with “the Church” as an institution?

LV: or maybe broader: what is the novel’s critique of catholicism and / or the catholic church.

JM: Or perhaps, is this an amoral text? Is this a text in favor of a return to paganism?

LV: what the hell is his critique of the church, or is it of catholics, society, those who go to church? i think he is judging and condemning humanity in a way.

LV: you know what else? i can’t help but feel that the translation creates some of the problems

you can add drama where it’s not; derail so much

JM: yes. how language is used in the original is, for me, the key to determining how “self-conscious” a text this is

LV: (from an article about the writer, http://bombsite.com/issues/110/articles/3364) “He seems to have tamed the monsters, to have confined them to those books of his infested with solitary, misunderstood beings, who are often also desperate, ill, insane, or senile. All of them are Colombian heroes undertaking, almost always, fruitless pursuits with no point of return.”

i wish tancredo would have done the killing.

JM: that’s the last line of the review, right there

***

Joe Milazzo is co-founder of the interdisciplinary arts organization Strophe, co-editor of the online journal [out of nothing] and proprietor of Imipolex Press. His writings have appeared in Antennae, Drunken Boat, Everyday Genius, H_NGM_N, Super Arrow, The Collagist, Black Clock, and elsewhere.

Laura Vena is a writer, artist, curator and translator whose work has appeared in Tarpaulin Sky, In Posse Review, Antennae, and the forthcoming anthology Dirty : Dirty (Jaded Ibis). Laura teaches Latin American Literature and writing and holds an MFA in Creative Writing and Critical Studies from CalArts.

Tags: Evelio Rosero, Good Offices, joe milazzo, Laura Vena

Smart review, smart reviewers. Wish I knew more of the novel’s frame/setup or of Rosero’s general practice (because I’m ignorant and under-read) but that’s just one mouse-click away, on the other hand.