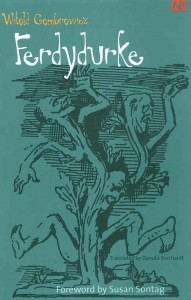

Ferdydurke

Ferdydurke

by Witold Gombrowicz

Yale University Press; First Edition edition, August 2000

(First published 1937)

320 pages / $8 – 25 Buy from Amazon

Talking past us, talking at us, at the open, the grand begin, from the onset another one of those sharp-edged misanthropic types, ever painful, absurd, so put-upon, the youthful thumb-bite, Lucky Jim, careening off the edge of thought, Under the Volcano, failing to recognize the genius before them, as though that “one-by-one box of bone” were such a shame for strangers, never to really know us, “ordinary fucking people”, sez our protagonist, Joey. From that position of unsteadiness, the feared impossible: not only the absence of reward, its perfect vacuum, sez our Joey, reversed through time to grade school again so that he might try a little better, having done something bad, having made a mistake. Luckily, it can be reversed.

How can we reconcile this, this poetic sensibility, with such devastating crudeness? Where is the perfect delicacy we’d been taught to cherish, the winking allusion, where do we find the much-needed descriptions of flowers, fields, a fencepost outside Dublin, waves, the blooming of the sakura blossoms, the vividity of maggots teeming in some peasant’s loaf of bread? How will we know how to think of trees if our books don’t tell us? There isn’t even bread here, all the crying children are assholes, the adults hem and haw and reinforce the base. Desire is the catalyst to every reaction, desire, especially those forms which fraternize with grasping, pinching, plumping. He reaches out and takes, he hides, all parties are whisked around like the Country Doctor, excepting those strangers who don’t seem in on the joke . . . but that would mean that we were in on the joke. Were we in on the joke? Where one of our sallow-cheeked Anglophile businessmen might pretend not to be in the apartment while some financial superior is banging down the door for up to five pages at a time, our rollicking little twit plays a long con through the door for . . . well, time kaleidoscopes, but he knows that she knows, she know or does not know, she would never let on, he would never let on. You thought of sex, then? How pathetic. A flower in a shoe provokes a scent-conspiracy enacted by a schoolgirl, but class warfare becomes a bonk on the nose. Anyway, back to sex. I’m not being coy, it’s just that the hierarchy of things is all messed up by Witty, and in the process he’s somehow managed to sneak a guffaw through the keyhole of a sneer. What is any one thing worth to another? I suppose it is true that I don’t know. The only difference between our world and his is that ours is occasionally illogical.

There is some other world out there where certain figures didn’t suffer the storm: Gombrowicz, Babel, Schulz, Brod. Kafka does too, the lucky devil. A whole separate slew of old white men, if a little more sickly than those we wound up choosing for the canon. Perhaps, in this other world, their full lives came at the expense of the popularity of a few of our dour old lepidopterists, those white-haired academicians who made ‘thrilling sentences’ and taught generations of young creative writing students the value of having that same sallow-cheeked businessman’s hands shake while he’s doing the dishes, just a few sentences before the end of the story. Couldn’t we afford to lose some of those endlessly relatable repressed suburbanites? Is it very hard to imagine a world where our writers reminded us, a little more angrily and a little more often, how near we are to nonsense? How funny that is, how sad it is? How horrifying the vacuum, how easy to gibber into it until it at least looks full? Wherefore the men for whom we golf-clapped, endlessly pleasing one another beneath the table?

It is very considerate of us to have excused ourselves for the inconvenience we posed, which did, after all, allow us plenty of time to swap spit-bubbles from Eliot, Pliny, Byron, Mistah Kurtz, to forget about Odessa in favor of some finely hyphenated adjective from the Odyssey, appended like a broach to the neck of a sentence. Still, what is it that drove Gombrowicz to stay in Argentina, what is it that drove an Argentine at the ‘opposite pole’ from the Pole to ask, “Who shall tell me, Israel, if you are found in the lost labyrinth of my blood?” Are we assuming that a people’s ability to save their own work from the fire exonerates us from the time we spent watching from across the street, if not working the bellows, if not ourselves the fire?

This is both before and during that. There is plenty to be outraged about, plenty to be heartbroken over. Franz Kafka (victim), The Trial, K.: responds to the unassailable, bewildering injustices the authorities pass down upon his head by desperately scrabbling to play by the rules. Knut Hamsun (monster or moron), Hunger, I: is gradually starved to death as he degenerates into the increasingly romantic delusion that he is the author of his own suffering. Isaac Babel (victim), Red Cavalry, all: into, into, into, this is what it is, horrible. Jorge Luis Borges (sympathizer), The Secret Miracle, Jaromir Hladík: the end is coming, acceptance is internal, can be a form of salvation, is ultimately irrelevant. Witold Gombrowicz (victim), Ferdydurke, Joey: be a problem, do not forget what it is they want from you.

And why not? Decades of Job doppelgangers, harangued & balding men attempting to keep their families together despite their sociopathically independent children, their wife-like shrews, their drawling, out-of-touch bosses, their minor crimes in the name of good morality, have taught us that empathy is pity is self-pity, that the world is a blistering rage of opportunists and atheists, and that we are stricken, basically good, weak only in occasional lapses from the light, lapses for which we are punished, if not by Justice herself, than by our own obsessive compulsion to honesty and belief in the social order. So yes, when Joey sucks us along after him, it is difficult to recognize this fresh empathy for what it is, the muscle is atrophied from disuse . . . but over time, we increasingly catch glimpses of something low, writhing in the deeps with startling strength. Who is this man who responds to hell with theories, who counters conspiracy and abuse with his own efficacious zealotry? What happened to the world of the anxious Western novel, in which ‘other people’ are bound together in a fraternity of Stodgy Reason while we fight desperately to remain afloat? It is gone, we are open, we are raging, raging, on and on, until we collapse into the ‘shelter in the arms of another human’, exhausted, furiously laughing, the ground shifting beneath us.

***

Gil Lawson is a writer from Santa Fe, NM. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in, among other places, n+1, The Hypocrite Reader, Bard Papers, and a series of chapbooks put out by Two-Suitor Press. He currently lives in Brooklyn, NY. Follow him on twitter @gil_lawson.

Tags: Ferdydurke, Gil Lawson, Witold Gombrowicz

I didn’t understand any of that, but it’s nice seeing Gombrowicz getting his due.

First 50 pages of Ferdydurke are so good.

Ferdydurke is one of my favorite novels of all time.

this doesn’t have subtitles but is still worth taking a gander at. from polish public television: http://youtu.be/gCcLhVe-y0Q

Would be interest in hearing why you like it, AD. Before reading thought it sounded like a book that I would love (love Gombrowicz in general) but was a little bored / found the narrator to be a bit “much” by the end // felt about it (a little bit) how people who hate seinfeld feel about seinfeld

Well, I really like Seinfeld :)

I guess I like the too-muchness? As well as how Protean the text is. I find all the interruptions delightful.

That said, my favorite stretch is definitely the middle, when the narrator goes to live with the very modern family whose surname I can’t remember off the top of my head—the whole stretch with Zuta and her unbridled youth, and her modern calves. And let me tell you, the second time I read that novel, I had just turned 30, and was working at a college, surrounded by 18-year-olds. And suddenly that book made a whole new sense to me…

I’ve been looking for a subtitled version for a while now.

The Youngbloods!! How could I have forgotten that??

Hey I like Seinfeld too! I’m with you re protean, interruptions, too-muchness (I liked the too-muchness in Pornografia), but I guess something about it started losing steam for me, around the half-way mark. I just started teaching a bunch of 18 year olds so much maybe I’ll revisit it soon heh

[…] Gil Lawson has an interesting piece on Witold Gombrowicz’s Ferdydurke at HTML Giant. […]

“Job doppelgangers” is good.

But wait: Kafka is by now as canonical as anyone. And really, he’s no “victim”. Tough dad, romantic complications, bureaucracy, ‘unfinished’ novels, tuberculosis: first-world problems. No more a “victim” than, say, Keats–who (to my knowledge), in his lifetime, got much worse reviews than did Kafka (whose stories were more published and circulated than one might suspect, albeit in a minority language and subculture).

“Endlessly relatable repressed suburbanite” — that’s so alien to Kafka’s esque?

And Street of Crocodiles and Ferdydurke are finished as often–and with as much pleasure–as is glittering Ada.

It’s become a trope, sure, but is contrasting the cut of lapidary sentences to the glamor of absurd persecution the most compelling modern polarity?

Maybe it is! –but it seems to me that ‘being put in a round room and told to sit in the corner’ respects no dexterity or formal subtlety.

[…] If literature needs to be something more than just storytelling, then perhaps one could argue with Maurice Blanchot that it only truly becomes grown-up when it “becomes a question” hanging over the space separating it from the world. By showing its sleight of hand, the novel can live up to Adorno’s definition of art as “magic delivered from the lie of being truth“, but it loses its innocence in the process. No longer is it possible for a serious novelist to go back to the “good old days” when — as Gombrowicz put it — one could write “as a child might pee against a tree“. […]