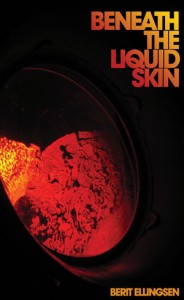

Beneath the Liquid Skin

Beneath the Liquid Skin

by Berit Ellingsen

firthFORTH Books, 2012

108 pages / $10.95 Buy from Amazon or firthFORTH Books

I met Berit Ellingsen on Twitter, where she shares photos of her two Burmese cats, Chloe and Dotty and where she frequently talks about the beauty of video game characters. I love a good cat photo like the rest of the Internet crowd, but it’s the way Ellingsen talked about the video game world that made me ask her to tell me more. I know nothing about video games (I’m plagued with heavy duty motion sickness which makes me vomit). Still, I found myself laughing at a video she posted in which one of her avatars dances to Up All Night To Get Lucky. I wondered if I was missing out by being unable to participate in the gaming universe. Five seconds into a video game, I confirmed that, until a magic pill is invented to keep my stomach settled, five seconds is my limit. I also discovered that Ellingsen is a compelling and extraordinary writer. Her story collection, Beneath the Liquid Skin is mesmerizing.

First, I must explain how I don’t usually read books like Ellingsen’s. The closest I’ve come is Alan Lightman’s Einstein’s Dreams in which there are short passages of true and fantastical renderings of the concept of time. In contrast, Beneath the Liquid Skin offers a much more varied range of stories in style and content. Each story is different from the last in tone, subject matter, and point of view. Usually, I read books where reality is pretty standard, there are no truffles growing on my lover’s leg (from “The Love Decay Has for the Living”) and the laws of gravity apply (“The light swells and swells inside us until we are ready to come off the ground like scabs from the skin,” from “Sliding”) or I’m asked to accept there’s order even when there doesn’t seem to be order in this fictional world (“0 is for wholeness and emptiness at once…”).

Ellingsen says, “When I wrote the stories I didn’t want to be constrained by ideas of literary genre or tradition. I just wrote what I felt like doing…There is currently a lot of interesting things going with some people writing in the cross sections between the literary genres, as hybrids, even between fiction and non-fiction and that’s great.” She says her “stories originate from dreams, some by photographs or images, others are inspired by various media or entertainment, but most originate from that empty space between thoughts where all stories come from.”

One image I find particularly relentless is in “The Tale that Wrote Itself”: “It was as if the buildings had tried to consume one another, each larger and more imposing than the next, but had bitten off more than they could chew and were now decomposing with their opponent in their jaw.”

Hard to forget that one, right? In fact, the story itself points to Ellingsen’s idea of storytelling:

“Can you decide what to think and when?” the farmer said, and looked directly at the king.

“Of course I can,” the king said. “I can think of whatever I wish, whenever I wish.”

“Can you decide how the thoughts make you feel?”

“Yes, of course,” the king was about to say, but then he realized he was less certain that he desired. “No,” the king finally said. “Sometimes the thoughts make me happy, other times sad, often when it is the least convenient, and I would’ve liked to have felt differently. The moods appear when they choose.”

“That’s how it was with the tale,” the farmer said. “The words came to the farmer like the wind and rain and the seasons. The farmer did not select them—they found him.”

Another memorable passage is from “The White”: “While you sleep your dreams are sampled like ancient water, your hair touched and your breath frozen. Someone thinks the foxtail is yours, others point out that it’s attached to your fur hood with metal and that the rest of your body is organic. This makes everyone laugh and want to touch you instead. You are petted like a cat, and your memories of the curious penguins and the professor with ice for eyes and the price of your funny hat are passed on like buckets of water to a fire.”

Ellingsen’s stories are like beautiful crystals, the kind that flashes prismatic colors. In them, you see yourself, you see the entirety of existence, you see how small you are and also how large. You’re acted upon by extremes of weather (“The White”), at the mercy of fate (“The Story that Tells Itself”), your own desires (“The Love Decay Has for the Living.”). She points to humankind’s impact on our planet (“Anthropocene”) and the violence we perpetrate on each other (“Sovetskoye Shampanskoye”). The ideas are grand, shocking, recriminating and redemptive.

Because of the particularly deliberate way she uses language and the format of the words on the page (she uses white space in short bursts of prose in “Crane Legs,” for example), I ask her about her choice to write in English as a Korean-Norwegian woman living in Norway.

She says she studied life sciences and neurosciences at the university level where all the textbooks and lab manuals were in English. It was too expensive to translate specialized materials for graduate courses. She noticed that English afforded her more range in her writing. The English words ‘lend’ and ‘borrow’ for example have only one counterpart in Norwegian.

I also ask her about a comment she’d made about how she could relate to Korean-Americans. She says, “In particular the part about growing up in a race other than ‘your own,’ and supposedly belonging to that race and culture in some respects, but also very clearly not being a part of it, because it’s not really your heritage or your background. Then, on the other hand, you don’t belong to your ‘root culture’ either, and can’t go back to it, because you’d be even more of stranger there since you grew up in that other culture…This becomes a definite dilemma and contradiction. I think many Korean diaspora share this, and it fascinates me that this displacement and ‘in-between-ness’ may be a part of the Korean diaspora’s ‘home culture.’”

***

Jimin Han (@jiminhanwriter) teaches at Sarah Lawrence College’s Writing Institute and lives outside New York City with her husband and children. Her writing may be found at NPR’s “Weekend America,” The Rumpus.net, and The Good Men Project, among other places.

Tags: Beneath the Liquid Skin, Berit Ellingsen, Jimin Han

[…] Writer Jimin Han has read Beneath the Liquid Skin for HTMLGiant! […]