Corner Stories

Corner Stories

by the Washington Heights Corner Project Community

Washington Heights Corner Project, July 2013

60 pages / $15 Buy from Washington Heights Corner Project

When I first started doing dope in my callow early twenties, I used to marvel at the raw story telling skill of the working class Vietnam veterans I bought bundles from, feeling like I had a God given duty to transcribe and capture their cant down wholesale in my journal. In the tradition of all those who slum, I felt like these men and their tales were my unique discovery. I’d absorbed the way the media uses drug users, the way they are placed in narratives as local color, punch line, or cautionary tale, and despite the fact that I was putatively joining their ranks, I wanted to pin these people to the page like so many trash talking, street wisdom dispensing specimens. I didn’t understand then that it was only in the first person that these voices had meaning.

The pieces in this collection, the literary magazine of the Becoming Writers workshop for participants of harm reduction organization the Washington Heights Corner Project, are indeed Corner Stories. As an injection drug user, I felt a great sense of comfort and familiarity reading these accounts, which sound so similar to the oral histories one hears passed down wherever drug users gather. It’s all here, from the lamentations about the difficulty of hustling, to the wily, wary disclaimers (“I wouldn’t recommend it to anyone”) and the paeans to the glory of the heroin of yesteryear (“a bag of dope back then was big…a lot of powder in one bag, enough to get two or three friends high,” Rubert Rey reminisces in “First Brush with Danger.”) Corner Stories also reminds me of the popular tradition of zines created by low-income rights and harm reduction organizations the nation over—Junkphood and the newsletters of Arise for Social Justice, for example. But Corner Stories is qualitatively a different project in the sense that finally, the oral history of drug users is being marketed and made accessible to the mainstream world.

Melissa Petro, editor of the lit mag and teacher of the workshop, writes in the introduction to the volume, “Maybe you have used drugs, or maybe you have never. Either way, there’s sorrow and pain in everyone’s life, just as there is joy. We all struggle to make purpose and meaning…” But most of the time, the struggles of drug users aren’t made known to the rest of the world, unless they’ve been watered down into the rote formulas of the recovery story or the special pleading of the confessional memoir. The simple folk wisdom of the subculture that I’ve heard while sitting around a circle fixing up, I’ve almost never seen written down, and certainly almost never for mass consumption.

It is these sorrows and joys that non-drug users are unfamiliar with—the elation of a homeless man out spare changing when suddenly presented with an envelope full of hundreds of dollars from a passing car (“when it hit eleven [bills] and it was still hundreds, I had a feeling like I took a hit. The sensation went from the tip of my head to my toes, a tingling feeling”), and the triumph of an exhausted woman hustling for cash when she sells her mother’s Mary Kay cosmetics for $200. These stories reveal the strain and grinding monotony of drug war induced poverty, and the incessant labor that goes into maintaining a habit. This is the sort of shop talk one hears among users, divvied up into dizzying highs and despair ridden lows:

The baldly stated realities of injection drug users’ lives utterly transform banal writing assignments like “tell us a story that takes place on a rainy day” or “tell us about your lucky day.” One rainy day story begins by piling on the tropes—it was “one of those days that you would prefer to spend at home in bed watching a good movie, covered up in a soft cotton comforter.” This cozy cliché is soon subverted when the narrator lets us know that because she is homeless, she lacks a bed, a comforter, a TV set, and even access to electricity. The only thing she holds out hope for is the possibility of spending that day with her estranged family, who may not even let her into the house once she arrives after taking the train all the way to Riverdale. Rain that is just another blip on the weather report to the bourgeois consciousness leaves the impoverished user in withdrawal with wet, useless dope, exposed to the elements. A lucky day is represented by the users’ own family deigning to let her talk to her child.

There’s an inexorable feeling of karma in many of these pieces. Sci-fi author Philip K. Dick has written that stories of drug abuse are not morality plays, as they are most often presented, but rather Greek tragedies. They are stories of hubris in the face of huge, implacable punitive forces, no more about ethics than an account of children playing in the street who are hit by cars. In the context of a billion dollar global drug war and America’s prison industrial complex, in the context of a recession and a black market that keeps the cost of narcotics gruelingly high, “what goes up must come down,” as the title of the first section of Corner Stories intones.

“If only I had made different choices,” Mike Lanzano laments in “Behind The Wheel”, “ I could have proved this truism false. Today, I’m working hard to ‘go back up.’ ” But choice actually plays little part in the overriding themes of fate, compulsion, and shitty circumstance in Corner Stories.

Thus, Michael Patalano’s “Payback” relates how he was broke and needed a bag, but his friend wouldn’t give him one because the last time his friend had been in a similar dopesick position, Patalano had refused to share. At first this seems an instance of the Golden Rule, but any junkie could tell you differently: in a black market in which the rhythms of our lives are dictated by an economy of scarcity, we’re often too constrained to be kind to each other, but we must suffer the consequences of our choices regardless.

There were things that made me cringe while reading the anthology—the constant use of NA/AA jargon, for one. But it’s something I recognize in the tales of drug users, and its presence is misleading. People who use drugs get their speech and attitudes colonized by the huge influence 12 step programs have on our culture, so when they write formally, or even when they speak informally, they feel compelled to present their lives with that sort of gloss. Most of the books and other media that a drug user will have digested about drug use are couched in the pious sentiments of recovery stories, after all. I’ve found, listening to the life stories of other drug users, that to get to the more nuanced truth, one must wait for an unguarded moment. And there are plenty here:

In Naomi Lily Madsen’s “3 Breaths”, for example, the reader encounters the pervasive fear of the police that often colors drug users’ lives. Madsen writes about not even wanting to look at the cops she passes on her way to the Washington Heights Corner Project’s writing workshop directly, not wanting to rouse their suspicions about what “this crazy white girl is doing running down their streets.” As she passes a huge group of people with “their hands up against the local supermarket wall and their legs spread as undercover and uniformed officers pat them down,” Madsen reflects that she knows the police vans these hapless, helpless people are about to escorted into: “I’ve ridden in the backs of them before, handcuffed and defeated.” She does look up to exchange glances with one of the arrestees, registering the hopelessness in his eyes, and she wishes she could call out to the group, to see if there’s anyone she can call to help them make bail, and yet, she records regretfully, she knows she can’t. Thus we see a theme that’s ruefully implicit in so many junkie narratives: our inability to help each other under the divisive reign of the drug war.

So one of the elements that really shines forth in these writings, an element Petro identifies in her introduction as “the connecting thread” in all these stories, is “the role of love”—the ways in which we as drug users can form community and family: “Loving relationships, these writers seem to say, are what keep us alive, and what gives our lives meaning.” Almost every piece in the collection begins with a David Copperfieldesque recitation of the writers’ origins, like a talisman the author is treasuring, a justification of their very being. In a couple of stark paragraphs, for example, L. Synn Stern finds connection in her genetic inheritance of small stature, which engendered her childhood dream of becoming a jockey: “My father is shrinking still. And he danced. He dances.”

But the most important person in users’ lives is one who is not just part of their backstory, but present in the struggle of living today, the way Donna’s Roc was “ALWAYS there, to save the day” even before they become lovers, “ALWAYS there” to extricate her from dire situations like this one:

Thus, true love in the drug world is the willingness to fight through the drug war with someone.

Or, sometimes, maybe it is the willingness to show someone how to survive it. Naomi Madsen writes an encomium to her harm reduction counselor, L. Synn Stern:

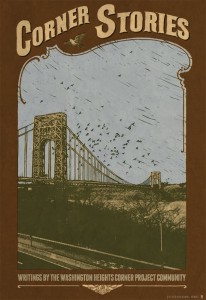

Secrets one is willing to pass along to those they may help—that may be the ultimate definition of dope fiend oral history. It is certainly the spirit behind our tiny canon of truly authentic testaments to the life—testaments like James Fogle’s Drugstore Cowboy, William Burroughs’ Junky, and Jack Black’s You Can’t Win. (Petro is aware of this influence—she quotes Hubert Selby Jr. in epigraphs and references the hobo past of the junkie tradition with the use of old time Americana font and art on Corner Stories’ cover.) But the problem with the slim selection of books preceding this volume is that they are subsumed in individualism. They are about the story of the drug user and his habit alone. Corner Stories finally has us speaking out as a community, bearing our tales together to other users and to the outside world.

To purchase Corner Stories, make a $15 donation to the Washington Heights Corner Project here.

***

Caty Simon is a small town activist, involved in the mad movement, harm reduction, drug users’ unions, sex workers’ rights, and low income rights. She’s also the co-editor of titsandsass.com, a blog by and for sex workers, and her essays and interviews have appeared in Emily Books.

Tags: Caty Simon, Corner Stories, Washington Heights Corner Project

An intelligent, thoughtful review. Thanks.

Thank you!