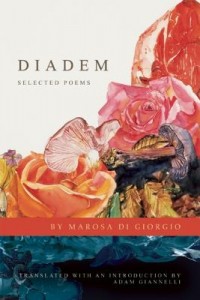

Diadem: Selected Poems

Diadem: Selected Poems

by Marosa di Giorgio

Translated by Adam Giannelli

BOA Editions, Oct 2012

80 pages / $16 Buy from BOA Editions or Amazon

In Diadem, Di Giorgio’s prose-styled poems are a collage of images ranging from the surreal to the innocent and childlike. Shadows stalking about the farm house amongst rose gardens, God appearing as a face and speaking, and children performing plays in the garden. Giorgio speaks to us through these images, playing with them, distorting them, and living in them; she speaks of “The owls, with their dark overcoats, thick spectacles, and strange little bells”, and “Virgin Mary, enormous wing over my whole childhood and the whole countryside.” These images, contrasted with the speech-like prose style, paints surrealistic and beautiful pictures of culture, childhood, sexuality, and death.

“God’s here.

God speaks.”

As noted by the translator of the collection of poems, Adam Giannelli, these poems could be read as a novel, cover to cover, or on their own as individual pieces, and they would still have the same power and depth. The poems themselves blend and blur the lines between each other, in effect recreating an idea of recalling memories of the past; sometimes fantasy, sometimes all too real, and always fleeting and hard to properly pin down.

The poems themselves are often quick to change in subject matter and mood; often these poems begin with something childlike, like a story or a memory.

“We would put on plays in the gardens, at twilight, beside the cedar and carob trees; the show was improvised on the spot, and I was always afraid I wouldn’t know what to say, although that never happened.”

The poems often quickly turn, however, such as in this fragment. What is meant by a play is quickly distorted into something else; be it the anxieties of adolescence, maturation, or something more so. What makes these pieces stand out is that sometimes it is hard to know exactly what is happening, but it doesn’t take anything away from it.

“The mushrooms are born in silence; some are born in silence; others, with a brief shriek, a bit of thunder.”

The flexibility Di Giorgio employs with image, as well as grammatical constraints, helps give the pieces a somewhat corporeal feel; there is some sort of otherness to them.

“Each ones bears-and this is the horrible part-the initials of the dead person from which it springs.”

The themes turn so quickly that the reader almost can’t keep up. First one has this image of a mushroom growing in the ground, but being born of thunder turns the poem; why would there be thunder? And then, the initials of the dead are introduced, so perhaps these are supposed to symbolize some sort of cultural thing; death and rebirth. However, the piece makes another turn in the very next line.

“But in the afternoon the mushroom buyer comes and starts to pick them. My mother lets him. He chooses like an eagle. That one, white as sugar, pink one, grey one.”

Here now the subject has changed again; perhaps the mushroom buyer is reaping the spoils of war? Perhaps this is westernization? Maybe they are just regular mushrooms? It is these parallels of images working together, juxtaposing themselves rapidly and fluidly, which creates powerful pieces of poetry all under a single breath.

Here again you see her flexible approach to grammar; using them not as a frame of narrative, but to give the words a sense of breath, pause, and motion; one that reflects both speech and thought blending together, giving the pieces a more natural and human feeling in each piece. You can hear the panic, the movement, the action; the locusts, with images of bone and death, cascading like waterfalls onto the small village. What you also get is the picture around the images; they might be the insects, or they could represent something else, but either reading is just as powerful. The flexibility of the language, whilst using these fleeting, collage like images, creates for the reader an endless possibility of narratives and stories within the lines themselves.

In using these prose-styled poems, Di Giorgio is able to take the strengths of poetry; the distillation of images down to their purest form, the uses of metaphor, and flexibility of language, to enhance these pieces beyond the idea of a short story or micro-fiction. The blurring of the lines between poem and prose serves these pieces well, giving these poems a story book feeling; like fables that had been passed from generation to generation, and with each telling the story had slightly changed. What is here, in print, is the distillation of memory, stories, and ‘real life’, into something moving and beautiful. And although these pieces can be quite surreal, the strength and emotion of them is still not lost on the reader. That is the true essence of these pieces; that they feel natural, real, meaningful, despite incorporating fantasy and surreal images.

The dead appear, lying down, or on their knees, and try to walk.

One glances leeringly at a dead blonde who stands out from afar.

But right away it starts to get cold. The sun goes black, leaving only

A ring, a raveled thread; birds chirp and fly to their nest.

A sheep lies on its back; with its hooves in the air.

And what’s below begins again to lower.’

These poems, or prose poems, are both unconventional and timeless, sharing the space of confusion and simplicity in the same breath. What Di Giorgio was able to do is share to us her own thoughts, fears, stories, and memories, in a way that makes one feel like they are their own memories; she connects us with her words, and shares with us her experiences. That is what makes these poems truly beautiful, and often moving; we feel these words, these memories, and these stories. We feel like the little girl in the garden wondering who the strangers are. We remember the shadows that moved around at night. We remember locusts, and we remember the animals in the forests. Although these aren’t the familiar images of our own everyday lives, one can’t help but feel like Di Giorgio is sharing with us something universal that we can’t quite put our finger on.

***

Rhys Nixon is a writer from Adelaide, Australia, who sometimes posts poetry and short fiction on his blog, rhysrhys.tumblr.com, when he isn’t watching too much television.

Tags: Adam Giannelli, Diadem, Marosa di Giorgio, Rhys Nixon