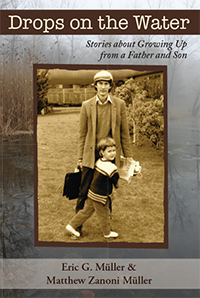

Drops on the Water

Drops on the Water

by Eric G. Müller and Matthew Zanoni Müller

Apprentice House, 2014

274 pages / $16.95 Buy from Apprentice House or Amazon

Vladimir Nabokov once said “…literature was born on the day a boy came crying wolf, wolf and there was no wolf behind him…Between the wolf in the tall grass and the wolf in the tall story there is a shimmering go-between. That go-between, that prism, is the art of literature.”

In their debut memoir, Drops on the Water (Apprentice House 2014), co-authors Eric G. Müller and Matthew Zanoni Müller conjure those dark, shimmering tales of childhood.

A collection billed as “stories about growing up from a father and son,” the book’s structure appears deceptively simple: a chronological staging of moments from each of these writers’ young lives. This, however, is where any pretense of simplicity ends. Not only do father and son appear as children in their own tales, they materialize in each other’s stories as shadowy influences hovering in the background, or at times, stepping forward and playing the roles of antagonist, shape-shifter, babe in the woods, savior. It is as though they have positioned themselves in a funhouse hall of mirrors, so that we get to see multiple sides of them, even as they––as narrators––attempt to contain our attention to the story at hand. This strategy allows the Müllers to take full advantage of the inherently unreliable nature of their first-person narratives and help the reader recognize the wolfish, the prismatic, aspects of their tales.

Eric Müller, the father, begins his story in rural Switzerland, where he rides crimson gondolas and tramps through wintry forests, before moving to South Africa where he encounters a phantom horse that forces him to consider his own mortality, hunts pheasants in Zululand, and befriends a thuggish young classmate whose mother feeds him a rich, oily soup that turns out to be swimming with chicken hearts. Yet despite the sly, fairytale quality of Müller’s prose, a ribbon of grim realism persists throughout. In one of the book’s most unsettling stories, he watches as two schoolmates torture squirrel-like dassies on the savannah by stabbing them and yanking the slick ropes of their intestines out and gleefully waving them in the air. Afraid of being shamed by his peers, the child pretends he isn’t troubled by this brutality, which we recognize as his own version of crying wolf. Even so, the wolf sinks its teeth in our narrator’s hide. “Two more suffered the same fate before we returned to the farmhouse. I felt guilty and sickened by the hunt…one thing I knew for sure, it would be a long time before wars would be eradicated on this earth.”

Time, too, plays a critical part in this memoir. Aside from the introduction, both father and son tell their tales in steady, chronologic procession. Again, the collection’s design turns out to be more complex than it first suggests. Because their stories, set decades apart, have been braided together, chronology soon reveals itself to be an illusion and it isn’t long before we discover that rather than moving forward in a direct and reasonable manner, we have unexpectedly looped back on ourselves. Additionally, the authors, who are now grown men, often recast their childhoods through the lens of retrospection, using present tense to describe past events while recounting present experiences in past. The effect is dizzying and delightful. Now we’re the ones who have found ourselves in the funhouse, caught in the Müllers’ maze.

Though the stories of Matthew Zanoni Müller do not feature the gothic landscapes of distant countries and instead explore somewhat more familiar terrain, his stark, dreamy voice and keen insight makes them no less bewitching. Rather than hiking through enchanted woodlands in Europe, we see him roaming the chilly aisles of a supermarket in Oregon, anxious and uncertain, later finding comfort in the simple pleasure of a licorice whip. The expansive African savannah is transformed into a cramped trailer powered by an extension cord. Here, he and his schoolmates watch an American action movie with a German antagonist, his friends sneering at the villain whose accent, he realizes, mirrors his own. As a child whose family immigrated to the United States from Germany just before he turned three, he struggles to make sense of his new home, where “everything is different afterward,” and “prevailing attitudes toward Germans so often seemed to look for that evil seed that must be inside all of us.”

One night, a prankish spirit takes hold of him and he sneaks out of bed and pushes his toys down the stairs, only to see the “pale angry ghost” of his mother emerge from the bedroom and break down in tears, not out of frustration, but in despair.

“She sits at the table with her hair over her face, crying quietly, all to herself, like we are dead…I hear cars going by in the street outside and somewhere farther way a siren driving fast, but it sounds nothing like the ones in Germany. It will keep driving farther away until the sound disappears, leaving us all here.”

Afterward, “the dark form of his father” scoops him up and carries him back to bed, where he lies alone in his room, lit by the cold American streetlamp outside.

Often rooted in loss and longing, the stories in Drops on the Water contain a distinct sense of wonder that lifts them from the gloom of troubled childhood narratives, and despite being a memoir, the collection manages to embody that fantastic paradox of feeling at once real and unreal. This, combined with the their trickster strategies of manipulating time and character, gives the reader the sense that the Müllers have summoned for us a half-remembered dream. Before long, we are seduced into those tall, shimmering grasses where the wolf resides, and in time it becomes no longer only the their tale, but ours too. This, of course, is the trick of all great artists.

“There are three points of view,” Vladimir Nabokov went on to say, “from which a writer can be considered: he may be considered as a storyteller, as a teacher, and as an enchanter.” A collection in which craft-focused writers, as well as readers, will find many pleasures, Drops on the Water succeeds in each of these realms.

***

Karen Tucker: The recipient of an Elizabeth George Foundation Grant for Emerging Writers, Karen Tucker’s short fiction is forthcoming in Salamander. She lives in Asheville, North Carolina.

Tags: Drops on the Water, Eric G. Müller, Matthew Zanoni Müller