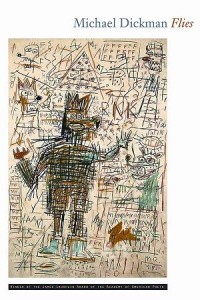

Flies

Flies

by Michael Dickman

Copper Canyon Press, 2011

96 pages / $16 Buy from Copper Canyon Press or Amazon

Upon a first reading of Michael Dickman’s Flies, a reader might be left with impressions abrupt and violent. Perhaps one cannot be blamed for this reaction; the collection oozes strangely enjambed lines and macabre content frequently addressing dark, untimely deaths. Flies, however, does much more than induce the unsettling awe an audience might expect from a horror film, although it does that, too. As a reader takes the time to know and understand the collection — perhaps not so unlike how time is necessary to begin to grieve and to start to heal — we learn that Dickman’s lines are not haphazardly clipped with the sole purpose of creating unexpected suspense and terror, but rather masterfully guide the reader with a humane, almost gentle subtlety.

Flies opens with the poem “Dead Brother Superhero.” The first lines read:

You don’t have to be

afraid (3)

Falling barely short of an end-stop, the first line, “You don’t have to be,” ever so subtly juxtaposes the state of being, via “to be,” with quite the opposite, the dead, as mentioned in the title “Dead Brother Superhero.” This comparative device, in combination with the apotheosis found within the title, results in a grievous, heartfelt magnification of the brother’s deadness.

At other times Dickman’s line breaks summon a subtle duality. In “Emily Dickinson to the Rescue”, the poet writes:

Her legs pumping

her heart

out (22)

Although the speaker states, “Her legs pumping,” perhaps a pumping heart is an even more natural image. Dickman, of course, resists this more traditional description and repetition. He does not write “Her heart pumping.” Instead the piece surprises us with “her heart / out.” Nevertheless, due to the visual layout of the stanza, it is not too far fetched to envision her heart pumping, as we the readers might even go so far as to imagine the slipping down of the verb “pumping” to substitute for that blaring white space. The audience is left with a delicate duality of sorts. We might visualize the image as written of a “heart / out,” perhaps as if wearing one’s heart on her sleeve, but there is also the quietly suggestive nod toward a heart pumping out as it might while bleeding out during the last moments of life.

The second section of the opening poem closes with the lines:

Any second now

Any second

now (4)

Dickman frequently resists more traditional forms of repetition. The phrase, “Any second now,” is repeated but with the variation of a line break. This technique creates an effect within the poem. The language itself is subtly ambiguous. Breaking the line “Any second / now” permits two reading. Firstly, we are allowed a reading identical to the first phrase without a line break, a straight repetition of what precedes. Additionally, due to the enjambement, a second meaning — that the “now” has actually arrived — is possible. If the poem stated, “Any second now / any second now,” we as readers would be left waiting with the speaker for whatever event he is anxiously anticipating. However, because the repetition is varied by the line break we may interpret the “now” both as not yet having arrived and also as having arrived. Due to the poet’s enjambment and, therefore, the emphasis of the second “now” which closes the section, we as readers can be hopeful but not certain that the awaited time has come.

All of the weirdly clipped lines draw attention to the rare but still regularly occurring longer, less obstructed stanzas within the poems. For example, the fifth stanza of “An Offering” contains one line that reaches across the entire page and then wraps around:

The sleeping bags are covered in tiny cowboys and floating lassos

spinning and repeating out into nothing (58)

More often than not, the poems found within Flies contain only one such stanza. These frequently provide a more concrete, although still often strange, image or thought that a reader might grab and hold onto. Such content is showcased as it is served to us in less obstructed stanzas amongst the almost overwhelming enjambment of so many others. With credit to this technique, perhaps these stanzas are not unlike brilliant bits of personal memories that we clutch so dearly as everything else becomes fragmentary. How subtly human!

Finally, a small handful of Dickman’s poems, such as “False Start,” contain primarily one-line and wrapped-around stanzas. “False Start” begins:

At the end of one of the billion light-years of loneliness

My mother sits on the floor of her new kitchen carefully feeding the flies

from her fingertips

All the lights in the house are on so it must be summer

Wings the color of her nail polish

I like to sit on the floor next to her and tell her what a good job she’s

doing

You’re doing such a good job Mom

She’s very patient with the ones who refuse to swallow

She hums a little song and shoves the food in

They still have all their wings

It takes a long time because no one is hungry (16)

At first, with disconcerting lines such as “Wings the color of her nail polish,” it might appear as though these dramatically short stanzas highlight each unsettling moment, action, and image. The effect, however, might be quite the opposite. Maybe this technique, with all of its white space, paces us from taking in the content too rapidly. Perhaps this repetitive approach numbs us from what might otherwise be swiftly overwhelming and all-consuming.

While Flies may be described as abrupt and even violent, it should not be argued that the lines, for example, are destructively clipped solely for the sake of mirroring and communicating macabre content. Rather, the devices within Michael Dickman’s brilliant collection are friendly provisions, which allows us as readers to remain human, not withholding the hope and strength necessary to do so.

***

Heather Lang is a poet and a critic studying with Fairleigh Dickinson University’s Low Residency MFA in Creative Writing program. Her poetry has been published in Jelly Bucket, The Del Sol Review and Ithaca Lit. She has reviewed for Gently Read Literature and her review of Mary Quade’s Guide to Native Beasts is forthcoming in Prime Number Magazine. Heather serves as Assistant Editor for TLR, The Literary Review.

Tags: Flies, Heather Lang, Michael Dickman

[…] Lang reviewed Flies by poet Michael Dickman at HTMLGiant. I mention this because we’re publishing an interview with Dickman […]