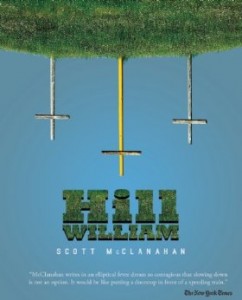

Hill William

Hill William

by Scott McClanahan

Tyrant Books, Nov 2013

200 pages / $14 Buy from Amazon

There’s a moment in John Fante’s The Road to Los Angeles wherein his protagonist, Arturo Bandini, has taken all the photographs of beautiful Hollywood starlets he ritualistically masturbates to in the closet into the bathtub with him to drown them, so to speak, and attempt to move on with his life. In a matter of three or four pages it distills the awkwardness and hilarity of growing up into a beautiful, imaginative vision of this young man thrashing around in the tub with photographs surrounding him, their faces beginning to run. Around halfway through Scott McClanahan’s newest work, Hill William, I realized that I’d felt the same sense of awkwardness and hilarity for the past 80 pages, only subsiding briefly when one tale reaches its close, and the next begins.

Fans of McClanahan are well aware of his ability to convey these qualities through a multitude of works. Be it his early collections of Stories, The Collected Works from Lazy Fascist, or the recent Crapalachia, I’m hard pressed to think of any writer working today who so seamlessly blends the horrific with the heartfelt, or small town American mania with the universal notion of comedy, and a desperate search for meaning.

Hill William, for me, feels a bit like the perfect blend of his early short fiction with the all-too-real tales of Crapalachia, while transcending anything thus far and reading like Geronimo Rex-Barry Hannah got into a bareknuckle boxing match with Person-Sam Pink. (This was another comparison that immediately came to mind, if you’ll pardon my digressive tendency.)

Hill William is McClanahan’s first novel, and yet it functions more like a novel-in-stories, the protagonist presenting the reader with any number of characters from his youth like Gay Walter, a “sissified” young man with a pet hamster named Hardees, or Derrick Anger, a boy who introduces young Scott to masturbating via a “1970s’s style dirty book that didn’t even have any pictures in it really but just these drawings of people having sex and these little dirty stories to go along with them.” With each chapter heading comes a new interior landscape wherein the narrator confronts some element of growing up, and yet for all the coming-of-age apparent in Hill William there’s just as much obsession with the surrounding community and the idea of taking on new lives and personalities to pass the time.

Early on, in “Rainelle,” the narrator says “I looked out over the continentals on the street below me and in these houses were people walking around in the lights they just turned on. I sat and felt so lonely because I was only one person and couldn’t be each of them.” This, by itself, got me thinking about McClanahan’s status as a sort of modern day Carver or even Faulkner, in his ability to sit down and narrate quick glimpses into such a wide range of lives. Some of that curiosity about this range of lives explored in his former stories seems to come out again in this urge to embody the whole community while telling one character’s life.

Later, Gay Walter begins singing Alabama’s “Roll On,” when the narrator observes “he was no longer Gay Walter but someone else. He sang and we watched and listened and he was no longer on a porch in the mountains, but he was on a stage somewhere. He was no longer lip synching to the radio, but he was our own private superstar. He was singing our song and we were singing along.” Suddenly the middle of nowhere becomes the center of the universe and it’s due to a mixture of McClanahan’s intimate prose and the unobstructed sight of a child. No longer are we as a reader in the mountains of Appalachia but traveling above it all with a gang of strange perverted nobodies desperate to feel comfortable. The microcosm quickly becomes the microcosm, the particular the general.

On this note of transcending circumstances, I have to include this beautiful moment, again from “Rainelle,” one of the early chapters: “And O if I could only tell you how beautiful it is to be a twelve year old boy, unwanted and alone in the world, and have your shirt off, riding your bike in the mountains.” It seems worth quoting in particular because in only a short number of pages we’ll have moved from the mountains to nightmarish youth-rape scenarios and into a fantasyland where America becomes covered in one woman’s gut and our narrator proceeds to stick a flag into it. I wonder what sort of MFA program could teach somebody to write so honestly, so perfectly, and then imagine McClanahan creating his own backwoods writing program where each evening students gather round to hear him speak from memory the tales of Stories V! and I realize he isn’t a modern day Carver, but something closer to Mark Twain: a humorist of the highest order.

Before moving on yet again (apologies) I have to return to this earlier-mentioned idea of McClanahan’s narrator embodying the voice of his entire community. In “Church,” between witnessing the moments after the rape of Gay Walter and getting a skidmark on the towel he dries off with after being baptized, Scott observes the singers in the church as “so ugly apart, singing on their own, but so beautiful like this when they sang together.” There’s something to this, a sort of narrative altruism where intense interiority suddenly becomes an omniscient perspective of life in these mountains. The narrator is quite selfless, while being as observant and obsessive as a Holden Caulfield, and you realize while reading that you’re witnessing an attempt to preserve the beauty of these potentially forgettable lives; as if each word is being screamed from the bottom of a mine that’s already collapsed upon itself, leaving just enough space for McClanahan’s story, before all is lost.

***

Tags: Grant Maierhofer, Hill William, Scott McClanahan

Here are a lot of ideas for any auther that want to incorporate masturbation into the tails:

Regards Knut Holt

http://www.abicana.com/masturbation.htm