HOPE TREE

HOPE TREE

by Frank Montesonti

Black Lawrence Press, August 2013

90 pages / $9.95 Buy from Black Lawrence Press or Amazon

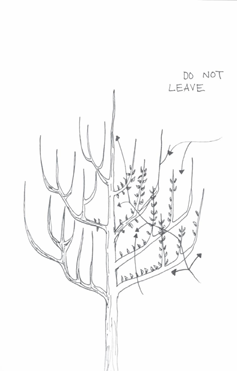

In HOPE TREE, Frank Montesonti literally prunes How to Prune Fruit Trees by R. Sanford Martin. Accompanied by simple drawings, lovely interpretations from the original sketches, the book is one of erasure.

Literary erasure is not without its critics. Jeannie Vanasco, in “Absent Things As If They Are Present” noted that “in 1820, in the preface to Prometheus Unbound, Shelley called complete poetic originality a ruse: “As to imitation, poetry is a mimetic art. It creates, but it creates by combination and representation.” HOPE TREE does just that. HOPE TREE is a risk, one that the author acknowledges in The Foreward: “I have hesi-/tated / I was aware// I have tried to make/ my instructions simple”

Illustrator: Miranda Polley

HOPE TREE is an espalier of words, both visually and metaphorically. The title, a play on the original, is interesting. HOPE is derived from a portion of the original title, How tO PrunE. Montesonti has tipped his hand. Pruning is initially a brutal activity, but also a hopeful one. When done correctly, the tree thrives, produces more fruit and becomes even more strong and beautiful. If not, the results can be an ugly mess, possibly fatal. It is all about the balance between aesthetics and necessity, a combination of knowledge with a leap of faith.

The same can be said for writing poetry. It is never easy to part with a word or favorite line even when it is abundantly clear that it must be done. As difficult as it is to do with your own words, erasing someone else’s words, while it might seem easy, is a much more complex and difficult task. This is not an exercise in editing. It is an exercise in pruning in the original sense of the word, to cut where the most growth will occur. Montesonti aptly notes “the coarse frameworks / may be very beautiful //as they// choke off the circulation” (32).

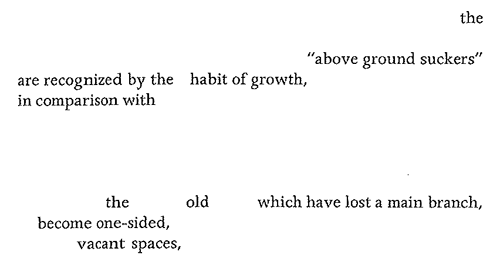

The book is designed to reflect the erased space in the placement and flow of the poems. The words and spaces fall exactly where they originally stood. It can be a bit disorienting. It took a bit to find a reading rhythm. At first, the pruning metaphor grounds the book, but then something began to happen. Clusters of words draw the reader. The surrounding space provides the break. The spaces begin to provide an opportunity to “manage the silence” (Mallarme).

For example, early on, references to “the above ground suckers” (13) and to “the old which have lost a main branch” (p 13) create space for the breadth of the human condition as present in the natural world. We are advised to “adjust the crop/ to what the tree can bear” (13). We know this. This is not new. The twist is a few pages later, where in a sea of white space we are advised to “get low / and govern accordingly” (17). It seems the rules of pruning, when pruned, have a modern, political bent.

There are truths here that trouble: “do not allow / the first season. Select” (36) that evoke Darwin and the resulting moral and ethical issues. Later, we are reminded to “Remove the one that contributes / the least” (53). It would be easy to dismiss this as cliché. That would be a mistake.

While the larger life questions are one thread, there are hopeful lines that inspire: “an imaginary circle / drawn around/ the future” (81) to remind of possibility – or not. There still is that circle, but it is imaginary. Maybe we do have more choice than we think or want.

Montesonti slips the best in seamlessly. In a simple line “There is time / to work your way inside.” (76) There is much silent space. The words stand alone in a tight knot in just the right place. It provides a pause. In the silence of the spaces, a sense of the double entendre emerges. Stop and smile. While the initial read wrestles with the moral and ethical overtones in a larger sense, now there is a playful hint or mirroring of the process the author used to actually erase and create this new piece. What a lovely and unexpected layer! “do not allow / the first season. Select” (36) takes on a whole new meaning.

In these silent spaces, the poet’s struggle with revision in the act of creation is illustrated. Montesonti has “hesi-/tated” much like the prudent gardener. “When cutting out, always/ disinfect the shears” (63).

***

Susan B. Gilbert is a poet/educator, very much at home in San Pedro, CA. Recent poems have appeared in Written River: a journal of eco-poetics, Sugar Mule, and LA Yoga. Her chapbook, Blue White Veil, (2012, Black Bamboo Press) is available through Amazon or on her website: http://www.bluewhiteveil.com/.

Tags: Frank Montesonti, HOPE TREE, Susan B. Gilbert