I’ll Drown My Book: Conceptual Writing by Women

I’ll Drown My Book: Conceptual Writing by Women

Edited by Caroline Bergvall, Laynie Browne, Teresa Carmody, & Vanessa Place

Les Figues Press, 2012

455 pages / $40 Buy from Les Figues Press

One half of a knucklebone or other object was a common object to carry in ancient Greece as an identifier to whoever carried the other half: a symbolon, the root of the word symbol. A symbol is a half-thing but of course most things are half-things; otherwise, what is language for? It fossilizes the potential of objects into meaning. Art has that to deal with. Language that knows it is art, on the other hand, seems to seek objecthood.

A walk through a regular art museum might have you thinking art is paintings. A distant second to that is sculpture, then drawings and prints, etc., and the farther the object deviates from these materials (or if the object was made for any other purpose than aesthetic contemplation, say, a quilt), not only is it less likely the object will be canonized (without any modifying category) as art, but the more the object will require mediation, textual padding between audience and object.

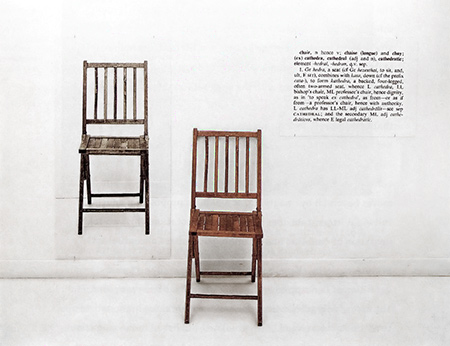

Perhaps what makes a work Conceptual, then, in visual art and in writing, is that as an object it attends to its physical deviation from canonical works but also shifts its weight to its context rather than its object. “A construction [is] a beginning of a thing,” wrote Yoko Ono in her Conceptual art book Grapefruit, and in this view, an object or a text is an idea’s anchor that begins, rather than completes, the idea.

The writings in I’ll Drown My Book are surrounded by frames: two introductions and one afterword by the editors. Each selection is then also followed by a writer’s statement, often a description of the work’s procedure or a response to the term Conceptual as it applies to her work. This textual-framing reminds me very much of how the visual arts are presented, propped by text panels in galleries and museums, battened by artist’s statements in magazines and catalogs. And ultimately, Conceptual writing itself is consciously framed by the Conceptual art movement of the 60s and its earlier predecessors in Dada and related movements; solidified by Duchamp in 1917 in his defense of his readymades which refused to supplement art objects with context but instead supplanted them with context. But Conceptual art, just as it is in writing now, never came to define a precise artistic practice, and because of this it became a convenient bag to throw anything that didn’t seem like art. In other words, art that was hard to sell: performances, happenings, instructions, installations, ephemera, sounds, silence. In dematerializing of the art object, artists were certainly responding to the hyper-commodification of contemporary art and its increasingly opaque economics.

Language, though, is already immaterial. Reading is nothing but pointedly conceptual—a reader sees symbols on a page, decodes symbols into letters and words, contemplates how those words work together—while looking at an object seems to reverse this process of signification: objects are not codes, and so we tend to encode them. And the more unfamiliar/removed the art object, the more this space requires language, which is the basis for Herbert Marcuse’s claim that art (unlike writing) functions only through estrangement. But if writing is an object, then Conceptual writers can reframe writing as “a figural object to be narrated” as described by Vanessa Place and Robert Fitterman in Notes on Conceptualism. One benefit of writing attending to its objecthood is how it can force the reader out of the regular reading method described above, in following, for example, Judith Goldman’s found political texts semi-obscured with lines, inserted x’s, slashes, sub- and superscript comments, irregular capitalization. In her statement she encourages careful attention to the texts (unlike some Conceptual writers who declare that one need not even read their work to understand it), how their “particularly strained relation to the contents they re-vision and present can make it exceptionally worthwhile to over-read them in detail, to attempt to follow the exaggerated, vitiated, or simply demented protocols of reading.”

In his introduction to Against Expression, Kenneth Goldsmith mentions the “re– gestures” of internet culture, retweeting, reblogging, reposting, etc, and how simply filtering the endless mass of data has itself become an end—not in making anything but choices; the often embarrassingly misappropriated term “curating” really a shorthand now for pointing, maybe a kind of pop asceticism in this flooding glut of content, a Pinterestism that winnows out selves. In rejecting primary craftsmanship of important handmade objects in art or renouncing all regular features of canonized Literature, most see Conceptualism as having made individual artistic virtuosity irrelevant (again), but perhaps it has just mutated. In his introduction to the same book, Craig Dworkin asserts that Conceptual writing “does not seek to express unique, coherent, or consistent individual psychologies,” which sounds to me more like a tame/failed project of Modernism than a new movement, so it was refreshing to see Laynie Browne write in her introduction that “the assumption of a dualistic paradigm which claims that conceptual writing creates only ego-less works is actually another false construction,” and the range of techniques in I’ll Drown my Book confirms that.

Similarly, Conceptual writing’s parallel trajectory with the internet and online writing is an easy thread for critics to pull in attempting to explain its existence, usually concluding that the internet is responsible for radically transforming the very ethos of all writing because technology alters the way people think, and such rule-based writing and text-appropriating is the perfect example. I’m not sure writers are now or ever have been as helplessly overtaken by their tools as the claim goes, and even if they sometimes are, it does seem critics like to forget that this too, as all art, is critique. Political and cultural criticism is a kind of Romanticism at a distance, and at the farthest distance of all is art that critiques art. And the flattened, impersonal text games of Conceptualism are not counter to this but at the very end of its arc. Recently, Johanna Drucker declared Conceptualism over, as its growth has accelerated “from banal to more banal” across generations, and what remains is only a lesson for us on the “unintended consequences of changes wrought by communications systems and their cultural effects.” Possibly, but I enjoyed this book. The range presented here from pleasant-but-mindless pattern-filling to some dazzlingly unfolding logic is not easy for me to dismiss. I went back to Joseph Kosuth’s seminal essay “Art After Philosophy” to see how he extracts Conceptualism out of art through its contextualization, well before the internet slouched up, claiming art’s functions have always “used art to cover up art” (depiction of religious themes, portraiture of aristocrats, detailing of architecture or landscape, etc.) and therefore “art’s viability is not connected to the presentation of visual experience,” but rather the conditions it creates. These conditions are its access point, as the book proves.

I’ll Drown My Book begins with an excerpt from Kathy Acker’s “I Recall My Childhood” from her retelling of Great Expectations, which, although it is only first because of alphabetization, serves as the perfect first piece in how it foregrounds one of the most prevalent methods of Conceptualism—the appropriation. Of the 62 writers represented here, I counted about half as making use of, or specifically referencing, other texts in differing degrees. The technique is not new, nor is it exclusive to Conceptual or even the broader “experimental” writing category, but it is especially concentrated here. Mere collage or “remix” I suppose belongs to now-dead Postmodernism, with its affirmative action, managed diversity, scrambling to add minorities to canon instead of tearing it up. When Postmodernism was quickly absorbed by the institutions it sought to critique, perhaps writers felt no longer content just to sidle up to “master” texts; instead, writers have come to occupy the texts themselves, through erasures, détournements, reproduction, repetition, re-telling, re-typing, plain plagiarism and theft—here presented as a feminist strategy. “Thieving denaturizes what it steals,” writes Caroline Bergvall in her introduction, a practice that “is close to Irigaray’s tactical notion of female mimicry. One is not one self.” It is dangerous work. In her afterword, Vanessa Place quotes Patrick Greaney in his “Insinuation: Détournement as Gendered Repetition” that appropriation is akin to entering “enemy territory,” and warns that “poets burrow into language, but they, too, are dug into, penetrated by the very language that they want to overcome.” Even those closest to visual art’s Conceptualism came to see how appropriation and context-centric art can seal itself into emptiness: Henry Flynt, who originally coined the term “Conceptual” in art, follows this process in his essay “Against Participation” to its logical conclusion: “The only possible opponent of the Establishment is the Establishment. Such discourse, such engulfing of opposition, produces a “no exit” universe. The circle closes; insurrection becomes a fixed point.”

In its Conceptual frames, this anthology is aware of that danger, and perhaps it is in doubled stance as Conceptual and feminist that stretches its awareness. While its true that the term Conceptual writing doesn’t “dictate or predict the writing” in the anthology as Browne notes in her introduction, there is some unifying features to feminist writing (and I’m using “feminist” as a placeholder, recognizing just as the book’s subtitle does (“Writing by Women”) that not all of these texts are necessarily feminist), which, in politics and language, does tend to collect content focused on the body as a site, as so often this single feature of female experience has defined women’s function and status in societies so long as they have existed. Most works in the collection point somewhere to female corporeality, or some in their statements, as Dodie Bellamy notes, “I do not believe the conceptual—especially in the work of women—can be separated from the body.” Certainly attention collects there, and at all points of pain and features of difference. Bellamy’s excerpt here from Cunt-Ups works to embody a text in corporeality’s own weird desire and revulsion, being both inside of a body and a body itself: “my fight wants to fuck your swollen pink and white spaces, to jostle you around gently until you turn blue.” A body, after all, grows but dies, and can both create and extinguish other bodies. The title of this anthology comes from Bernadette Mayer’s use of Prospero’s cry in The Tempest, as if the anthology itself is a body pieced together, sustained in the biosystemic exchanges between the art and its own thinking, its digestion, validating the fragility of this life process—and so, as Browne says, “if a book breathes it can also drown.”

Some of the pieces I liked best were Rachel Blau DuPlessis’s excerpt from Drafts, which she describes as “torqued” versions of “certain key male-authored texts of long modernism”; the selections from Bhanu Kapil’s Schizophrene; Ryoko Seikiguchi’s sensory poems which are presented without an accompanying statement; a section from Renee Angle’s WoO comprised of “spliced” voices of Mormonism, from religious founder Joseph Smith to mailbomber Mark Hoffmann; Katie Degentesh’s poems complied from children’s writings about sex culled from internet searches; and Jen Bervin’s gorgeous pattern samples created with letters and symbols on a typewriter, inspired by Anni Albers’ typed designs and mixed with quotes from others associated with the Black Mountain College. For better or worse, this anthology has enfolded most movements in experimental writing (flarf, concrete poetry, L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E, post lyric, post language, a tonalist, etc.) in building its case for Conceptual writing, which mirrors the state of contemporary feminism, diffused as it is now with Freud’s key influence on the wane in literature, its kaleidoscopic multiplicity and channeled interests a portent of change.

I found it disappointing that the reproductions of images (erasures, concrete poetry, drawings, photographs, embroidery, etc) were often of poor quality, or too small, as with Kristin Prevallet’s photographs of her “Blue Marble Project,” which are presented in a tragically tiny cluster, too small to for their proportionate detail. And the organization of the texts into four chapters provided thoughtful resting points in what is a pretty long book, but the names of these chapters (Process, Structure, Matter, and Event) seemed puzzlingly arbitrary or vague, as most of these works, it seemed to me, could appear under any one of these headings.

When Vanessa Place collapses the subject and the object of art/viewing into a “sobject” it is like Richard Wollheim’s paradox of “two-foldness” in a painting: it is both surface and content, impossibly plainly there, to look at and to look in. It can be a decorated concept. Or it can spoil itself, thank goodness. It can look at its own illusion; it can worm into old important ones. In writing, language is already a found thing, a massive appropriation set whole upon a mind, and when interest in its loveliness or intricate networks painfully exceeds the critical force of an art-gesture the concept is a hostage: how beauty can stunt us. For all the self-certifying supports surrounding the writings in I’ll Drown My Book, what caught me was the protrusion of the texts, their halfness, extending, as Chus Pato’s Hordes of Writing starts, “From the other side, where we’re alone with time”.

***

This is Part 2 of a week long feature on I’ll Drown My Book, the new anthology of women’s conceptual writing out recently from Les Figues Press. Read Part 1 here.

***

Molly Brodak is the author of A Little Middle of the Night (U of Iowa Press, 2010) and the chapbook The Flood (Coconut Books, 2012) and is the 2011–13 Poetry Fellow at Emory University.

Tags: I'll Drown My Book, Les Figues Press, Molly Brodak

[…] Tuesday – Part 2: Review by Molly […]

[…] This is Part 3 of a week long feature on I’ll Drown My Book, the new anthology of women’s conceptual writing out recently from Les Figues Press. Read Part 1 and Part 2. […]

[…] fragments are molly brodak on i’ll drown my book Share this:TwitterFacebookLike this:LikeBe the first to like this […]

That’s nice: does one find language, or is one found by it–written into writing?

[…] anthology of women’s conceptual writing out recently from Les Figues Press. Read Part 1, Part 2, and Part […]

—Eros the bittersweet, Anne Carson

[…] new anthology of women’s conceptual writing out recently from Les Figues Press. Read Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part […]

[…] Tuesday – Part 2: Review by Molly […]