In the Moremarrow / En la masmédula

In the Moremarrow / En la masmédula

by Oliverio Girondo, translated by Molly Weigel

Action Books, 2013

93 pages / $16 Buy from Action Books or SPD

the mix

yes

the mix I stuck my bridges together with

That first line is beautiful & on one level it seems a sort of how-I-wrote-my-book-and-so-can-you! treatise by Girondo. They are the last 4 lines of In the Moremarrow‘s first poem, The Mix

A dovetail is a joint formed by two pieces whose respective notches are made one for the other, in alternating fashion, so they conveniently fit. Here, the dovetails are undone, & instead we have for example soulmortar, an unlikely union of the ethereal intangible but vital, with the crushed inert material. Which, in creation myths, sounds like the soul blown into dust to animate a person. Perhaps, then, this is not so foreign. It is more primordial marrow. The mix seems to refer, then, to this poetics of uniting the disjointed, of mending broken ligaments, & the “bridges” are the compound words themselves, the neologistic portmanteaus

It is hard to say what stubborn female couplings refers to. Maybe something about the male poet accepting his anima, that female part of him that is stubbornly there but his machismo stubbornly rejects. This is a reach, as psychoanalysis is a reach. The “ex-she” seems to support it, & the several later poems’ repeated references to the ego seem to support it, & the erotics of “the mix” seem to support it, but it still feels like conjecture

Every left page gives the original Spanish version of the poem, and the right page holds the translation. I notice the Spanish helps. The original version of that first line is two

la pura impura mezcla que me merma los machimbres el almamasa tensa las tercas

hembras tuercas

English grammar now is largely gender-neutral, and Spanish grammar isn’t. Every noun & adjective in this sentence is female (ending in -a or -as) except for two. On a macro level we at least can say that “female couplings” refers to the writing itself. The writing is self-referential. The universe of En la masmédula writes its own rules & thereby writes itself into existence. Perhaps this explains its lack of proper nouns; on one level, it has no need to tie itself to the World as we know it, it needn’t be referential, it loves itself into being, it is self-reverential. It ties itself to the Word. It hermetically seals itself

But on another level, no. It hermaphroditically seals itself

Because it rewrites itself by correcting the mistakes of our World. The mistakes of our World embed themselves inside the grammar that we use, those stubborn couplings that lead us towards fixed fragmentations, binary perspectives, formal & social discriminations. Therefore the recombinations in this book are all still legible, because they adhere to grammar rules but comment on them while deforming them. “alma” for example means soul. It is one of those strange nouns with a feminine ending (alma), but is nevertheless considered a masculine noun, hence the male article “el.” Combining “alma” with the feminine noun “masa,” however, creates a Word of indeterminate gender, but the “el” still precedes it. This seems a problematization. “masa,” in fact, means flour, it is the baseline substance for sweet sumptuous cakes, for savory bread of the Earth, etc.

“machimbres” isn’t a word. It reminds of the word “machismo,” a word English has imported, & of the word “chimba” which can mean the opposite bank of a river, or a pigtail, or a piece of meat, etc. It also sounds like “machihembrado,” a dovetail joint, hence Weigel’s translation choice. It seems again though that this dovetail has been pared down, to remind us of all its assemblage, & question gender once again. To undo the dovetails, quite literally. A beautiful translation choice. It bridges shores. The shores Girondo sticks his bridges with

Translation is hard.

*

solicroak

prefugues

sighspirits

selfsoundings

inlabyrinth

ex-she’s

soulmortar

*

A lot of poems end on their own titles, creating a feeling of being in an enclosure. This is a bizarre feeling, because the poems are intensely lyrical without being confessional or “sincere” or narrative in the way the Lyric I often attempts to be; instead it is like handling a ball of pure psychic energy. The poem entitled “You have to look for it” has three stanzas, each of which ends on “for the poem,” which inscribes itself within the title’s “it.” The first line of the poem goes

In the eropsychis full of guests then meanders of waiting absence

Which is, like, incredible. But once again, very gestural. It once again informs the readers of the poem’s motive & the poem’s dimensions. It is a meeting place, a delimited house, a hovel of guests, entering the poet’s eroticized ego; it couples. There are other people there, straying, erranding

Here, in this book, it seems the ego & eros are interchangeable. There are echoes throughout…echo itself in fact becomes the sort of bridge between ego & eros. From “Even dying her”

the pockmark

new gorgon love medium olavacobraniagara erect entire swoon

that ululululululates and arepeggiospiderscratches the ego breath core

ululate, to howl, will be echoed two poems later (unhowled nightomb). Howls echo. Love for Girondo is a force that howls out. It finds its entrance & its exit – its pathways for transference & for spillage – in holes, in wounds, in the pockmark. A gorgon’s love is violence, it stones another with love, with Medusa gaze (En la MasMedusa). It is liquid (…niagara…) & drowning. The ego breath core is aligned with music, with scratches, with arachnid limbs, & with breath, exchange, essence. The poem once again creates a closure, by ending on the line “even dying her.” So what we have here is the description of a system. We are inside it. We are exposed to its symptoms

In the poem Plexile, the page topography is different. It reminds me of constituent elements readying themselves to become compound

Again, we have notions of wandering, of the ego’s fluidity, of echo (& perhaps that’s what this is, an echochamber, this entire book, each dies but reverberates in some elsewhere, takes new fainter forms later recognizable) & the therefore, the grammatical ergo that allows the manifestation of the ego in Word.

*

The way I sum En la Masmédula is this: love is ambitransitive. “I love” is an acceptable intransitive. It needn’t take an object. It needn’t take a lover. Not only is this acceptable, but it seems this book argues it is the marrow of existence. Love is the essence. W/r/t mas, which means “but,” I eat I shit I joy I suffer I I walk I shiver I bore I bore through, but I love. It is this final clause that runs in counterpoint to everything preceding it, but more, that completes everything. Everything I do is everything I do, but, at end, shot through with love

But my love takes partners, too. I love Mom I love Dad I love Jessie Ricky Jesus RuPaul Beyonce I love Chad Leif Alex Rob Megan Carrie Will I love Heidi. The list could, & does, go on. If love is the essence of things, the essence of love is More. Ergo más, meaning “more.” Love is, by nature, a coupling thing. It is transitive. It takes an object. And if love takes an object, love conducts violence. The ego’s eros makes echo, grows. And suffers. And loves. And problematizes; who wants to be an object? Who wants to be subject to objectification? Well, grammatically, everyone. Ergo, oh god

I’m not calling this book one-note. It’s more like a Waterflute with 45 finger-embouchure holes. There are 45 mouths. Plug the mouth with a finger & the blockage of the water will create a sound, a buzzing or a pure ringing. Or put your finger in more mouths, & you have what seems like infinite polyphony, pure potentiality of difference. But the essence of the instrument is water. Variations on a theme of water.

*

The way I sum In the Moremarrow, though, is the long way.

*

Molly Weigel’s Translator’s Introduction takes up the book’s first three pages. It is elegant. It is split into two short sections. The first section is about Girondo & the original publication of En la masmédula. He was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina in 1891. He was a central figure in Latin American modernism, but was friends with Spaniards like Federico Garcia Lorca & Rafael Albertí. En la masmédula’s stature is great, its influence widely felt, but the book is largely untranslated. This introductory passage I think offers reasons:

“En la masmédula (In the Moremarrow) (1956), Oliverio Girondo’s final book of poetry, consists of 37 lyrical, passionate, nihilistic, profoundly multivalent poems. Like Vallejo’s Trilce and Huidobro’s Altazor, with which it is frequently compared, In the Moremarrow forges from the Spanish a new poetic language with its own psychic vocabulary and syntax, constituting a journey into the uncharted space of whatever “more” the marrow of language may or may not hold.”

This book is hard to write about, around, through. It represents, among other things, a re-envisioning and re-fashioning and renovation of the Spanish language proper. For this reason it is full of neologisms created via new word compounds, new combinations, then recombinations of those prior new combinations: basic linguistic smelting. In essence, it’s about form. If language is promethean – an unstable ground both charnel & fructifying, forever recycling & in-phase – the question seems to beg, is there marrow? Is there an authoritative, origin-al essence to be mined at the bottom? Or is it just turtles all the way down?

This either/or question is engaged by the book’s very title, En la masmédula. I want to explain

There is “mas” & there is “más.”

*

“mas” means “but,” a grammatical conjunction, meant to indicate something in counterpoint, something exceptional, something distinctive

But

“más” means “more;” it is a determiner of nouns, implying an addition, a repetition, a replication

The first deals with the subtractive, the distinctive essence; the 2nd deals with the additional, with excess. We have here competing notions: Substance distilled vs. ecstatic ejaculation of substances

Or grammatically speaking, the definite article v. the indefinite: “The” v. “A(n)” or

We can look at this erotically, because that’s fun. What we have here is Reproduction vs. Fucking

The translator chose más, the More in the Moremarrow. This makes sense. The ButMarrow sounds horrific

But it seems the preservation of the tension b/w the two is important. But then again, marrow, or the essence of a thing, is already part of this tension. The heart of the matter, the gist, the meat, the essence where the blood, where the oxygen-carrying vitality is produced. We already have médula, or medulla

So we choose More, but because More is Más, how do we justify Masmédula? The Mas has no tilde

So we make an inference. Since no one Spanish word can carry two tildes (másmédula has 1 too many tildes, it is more than it can grammatically sustain) we imagine that “mas” was meant to have one. We transgress

It is interesting to me that the temptation is to choose “more,” but one cannot get there grammatically, one cannot break the rule of adding a second tilde. So the necessary & organic transgression takes place in the imaginary. Maybe that’s what “more” means, it is the imaginary added to the core, the tension against what is

& at the same time of course maybe absolutely not

but if it is, maybe that’s the vacuity of the poet, knowing how to start from void & flesh it, make it taller, give it a halo, haloed void, the illicit tilde as the halo

& at the same time of course maybe absolutely not.

*

artmaking

armtaking

taking up arms

taming up arks

*

“Molly Weigel’s Translator’s Introduction takes up the book’s first three pages. It is elegant. It is split into two short sections. The first section is about…”

The second section is called “In the Middle Version.” It is two pages. I quote

Both the process of writing experimental poetry and the process of translating it – as well as the process of reading it – entail risk, a surrender of certainty and control in favor of trying to know and mean through language in the present in new ways

This seems to be the question at the heart of the book, enacted by its constant linguistic slippages. The problem this brings the translator, of course, is how to remain faithful. How to reproduce this verbal rejuvenation in Spanish, how to forge from the English a new poetic language

Faithfulness may be a practice rather than a result. In this case, for me, faithfulness involved a ready index and middle finger obsessively leafing dictionary and thesaurus hour after hour to create what I came to call “the middle version”: a working version of the poem that included all of the possible meanings I or the dictionary or thesaurus or Internet could think of both in Spanish and English, including sound quality, interconnection or threads of meaning, ambiguity of syntax or reference, odd glancing notions. It contained the slant of my personality and point of view and present experience, but I made it as big as I could, making myself bigger in the process. [Italics mine]

I added emphasis here because I found interesting the premium placed on scholarly pursuit & identification of the finite number of empirical meanings within the poetic text. That’s a clunky sentence, & I meant it to be; it sounds more like a scientific process – based on observation & later analysis of empirical data in a controlled environment – than a poetical one

Maybe this is necessary. I don’t really know. I know that analysis is a fundamental part of translation. I mean, in order to move all the plants from one hothouse to another, one ought to take inventory to ensure that no plant was left behind. Fine

But with poetry…let’s say some mountain hermit in Argentina has cultivated a garden. It is a simple garden, of only one sort of plant, & so it is strange (poems are strange, obsessional), it is an arrangement of Cordon Cacti. These only grow at high elevations in the Andes

That hermit just died & that hermit’s daughter, who lives in Spring Green, WI, America, whatever, loves her mother & loves her mother’s cacti & loves their arrangement & wants them moved exactly as they are to her backyard. As a memorial to this woman & the beauty she cultivated & to enrich the Midwestern landscape with something completely new. This is understandable, and this is understandably impossible. The climate is different, the soil is different, the seasons are different, the elevation is different, the maturity of the plants is different – they were young once, they grew once, they aged, & so the views have changed – & for these reasons too the Cordon Cacti must be different. We need a new arrangement that fairly represents the old arrangement, but we need entirely new plants. We cannot simply transplant them, we must translate them

Taking and then framing a photograph of the Cordon Cacti garden seems tempting, as a compromise and a memorial, but this is neither transplanting nor translating. It is simply a record of a static moment. It is not a garden. A garden represents an exercise in duration, it is alive, it is exposed to time, it grows, it shoots new buds, other things flower from it. The garden is never so isolated from its milieu, the garden responds to its environment & the environment responds to the garden. There are birds. A photograph, in this case at least, is not a poem. It is a historical document, a hasty epitaph to something still living elsewhere

Translation necessarily fails to be faithful; the most faithful translation, faithful in the classical sense, in my mind would be a xeroxed copy of the original poem, & even then, its status as a copy undermines its authority, its due respect. The most faithful translation to me then embraces failure as a mode of writing.

*

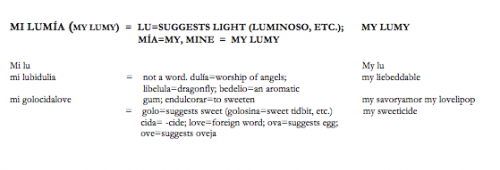

The name the “The Middle Version” is apt. At the end of the book, under APPENDIX, is an example of a translated poem in its basic procedural stages, in 3 columns. The first left-indented column is the original Spanish poem. The third right-indented column is the finished translation. Between the two is the center-aligned column, the Middle Version.

The middle version makes apparent the research the author has done & the multiple associations she has drawn. It’s impressive. It builds credibility

The format of it is quite lovely, it is pleasurable

There are moments in the middle version, in column 2, that actually appear quite poetic, whether intentional or not. “love=foreign word” I wish would make its way into the new poem, the new translation. That’s beautiful

This too points out something for me that is disconcerting. If I see more poetic germinations in the middle version than the final, maybe it’s time to cut the middleman, as it were. What I mean to say is this

Mi Lumía, the poem, is a poem that generates itself in response to its own play. The prefix “lu” couples with unlikely words, it keeps regenerating new combinations with the same root, but in response too to itself, to the lines that precede it. We see an organism build its limbs in response to each limb just built. Mi lu builds to mi lubidulia. Mi lubidulia builds to mi golocidalove. The semantic & sonic qualities of one line establish the bedrock for the line following

My Lumy does this, too, at its best moments. This entire book does this, in fact, at its best moments. my savoryamor my lovelipop my sweeticide build off one another rather organically. The translation doesn’t seem to me to be a simple translation; it seems to me to be a new, discrete poem, not having to rely on the source text

But the first two lines of the translation are confusing to me. Compare “Mi lu / Mi lubidulia” to “My lu / My liebeddable.” The first establishes a precedent of fixation, of prefix-ation, of words built sonically & meaning apparently generated by chance encounters, by amorous verbal couplings: lu (light) bi (two) dulia (angelsong). In fact, “lubi” is a mirror image of “duli.” And so once again, a very organic process of language construction

The second, well, isn’t/doesn’t. It does not build from one to the other organically, there is no repetition of the prefix (lu to lie); the connection between lie & bed is predictable and, strangely, it seems “liebeddable” was chosen simply as a sort of off-homophonic translation of “lubidulia.” In this way the translation seems to be written in direct response to the source text. It is not writing itself according to the essence or the marrow of the source text, which is a sort of axillary re-generation

At its best moments, In the Moremarrow finds the essence of the source poems & rewrites itself with that same idiosyncratic element, letting itself grow into a new poem that is essentially the same as its progenitor, but also “more.” There are several of these best moments. The majority of the book is such best moments

I think this book is extremely important. Both to expose us to Girondo’s work & to get us thinking about translation. Action Books has a knack for finding works like this

Translation is agonizing. I don’t trust it as a system. I trust it as a mode of writing poems

Poetry is agonizing

*

out of the fertile mother of godcome

comes from the poem Morepleonasm. And then, from one of my favorite poems, Oozings

oblivion its unseeing tapir mask

***

Jared Joseph is boring.

Tags: action books, In the Moremarrow, Jared Joseph, Oliverio Girondo

Wow… this article really makes me want to get good enough at Spanish to translate poetry…

sohoearn

In the Moremarrow / En la masmédula by Oliverio Girondo | HTMLGIANT