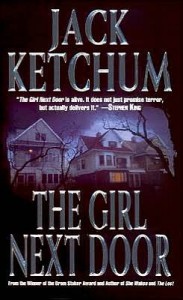

The Girl Next Door

The Girl Next Door

by Jack Ketchum

Leisure Books, 2005

370 pages / Buy from Amazon

One principle guiding this year’s reading has been to delve more deeply into what’s filed under Horror. When people ask me what kind of stuff I write, I always struggle with that word, never quite sure what it’ll mean to them when I do or don’t use it. I like the word, and generally think of what I do as drawing from that side of things, but I’ve never 100% known, reading-wise, what it encompasses.

So this year I read some of the classics and tried to ground myself in the contemporary, English-language tradition of the genre: Stephen King (whose name has obviously loomed forever but whose work, aside from On Writing, I’d never really read), Thomas Ligotti (phenomenal, someone I hope to write about soon), Todd Grimson, Ramsey Campbell (cool in both senses of the word), Joe Hill (got a huge kick out of NOS4A2, though probably enough has been said about that book by now), Shirley Jackson, Dennis Etchison, Robert Shearman, Laird Barron, Bret Easton Ellis (crucial in his own way) … and Jack Ketchum.

Of everything I took in under these auspices, Ketchum’s The Girl Next Door hit me hardest. A few months later, it’s still in there, growing, helping me not forget that life’s a problem.

I could go on about its take on 60’s small-town American life and its amazingly apt and tender portrayal of boyhood and the loss of innocence and the rush of discovery when one’s own destructive urges first flare up, but what really tore this book into my lining was the surprising but inarguable way it distinguished the Banality of Evil (which everyone has) from something deeper, worse – call it the Uniqueness of Evil (which only some people have … or maybe they’re not even people at that point).

The premise, based loosely on a real crime committed in Indiana in 1965: a smart, hip NYC girl, Meg, and her disabled sister come to stay with their cousins and their freaky, bitter aunt in a New Jersey town after their parents are killed in a car crash. David, the narrator and boy next door, falls for Meg as soon as he meets her. Her worldliness, older-seeming-ness, the fact that she’s not a tiny-minded bigot … she doesn’t have to do much more than show up to introduce him to his “adolescence head-on.”

Things take their sweet, romantic time, all summery creekside flirtation and town funfairs, until Ruth, the sado-aunt, decides to imprison Meg in her bomb-shelter basement, claiming, in a fit of sanctimonious insanity, that she’s gonna teach the girl how not to be a slut and thereby spare her the grim fate of all women.

Thus the book enters its Banality of Evil phase, incrementally uncovering the dumb violence housed in Ruth’s sons and their neighborhood friends, David included: the way in which they all, horny and hopped-up on monster mags and hearsay, can’t resist the temptation of a hot girl chained and the freedom to lord themselves over her.

Under Ruth’s strict guidance, they torment the captive, dancing up to and back from the edge of sexual transgression, and torment themselves as well, wondering how far they’ll go, and how much it means to have an adult’s permission to go there … wondering whether going too far is inevitable or forbidden, and whether the deeper regret will prove to be doing or not doing the things they most want to do.

David hovers unstably between wanting to protect this girl he’s fallen for and wanting to relish the chance to see and touch her naked, to replace his normal teen fantasy with abnormal, unearned reality. “She was all I knew of sex,” he admits, “and all I knew of cruelty.”

Overcoming his initial revulsion and sense of wrongness, and thereby dismissing the only warning that could have saved Meg’s life because things are just getting started at this point, he stands by as “shame looked square in the face of desire and looked away again.”

All of this emotional development isn’t just the perfunctory “make the reader care about them so it’s scary when they get slaughtered” legwork. There’s something in David’s relationship to Meg and to the other, more easily unhinged boys, that rings absolutely true to the feeling of growing up and wanting to belong both to the species and to yourself, and to be one with your friends while also pursuing the things that take you away from them – both love and lust, doled out in equal parts tenderness and ferocity.

This whole Banality of Evil section is a masterpiece of denial and self-justification (and as good a Holocaust metaphor as I’ve seen), charting the ways in which David and the other boys combine permission and desire into a driving force that grossly trumps mercy. It’s as if the extremity of it all, the sense that it couldn’t be happening, excuses it, making it almost as though it isn’t happening, or at least promising that in retrospect, once they’ve had their fun and rite of passage, it won’t have happened for real.

As they let this current carry them away, the basement becomes not only a torture chamber but a kind of shrine, a place for the worship and adoration of an idol. It’s where these boys come together in the dead summer to “make a sort of judgment on … beauty, on what it meant and didn’t mean to us.”

What makes this all extra poignant is Meg’s proud, enlightened belief that it has to end somewhere: if she just maintains her courage and dignity long enough, she’ll be let go, and they’ll all be able to put it behind them.

Perhaps she even sees it as a kind of degradation that, if you just live through it, makes you stronger and your degraders weaker, a defining trauma on the hard but requisite road to adulthood, as if the pain were in fact a transfer of power from them to you.

David concurs, certain that, “by September it would be over, one way or another.”

The book plunges into dizzying horror when Meg and David realize that no such breaking point is coming. It will indeed be over by September, but not in the way they’d foreseen.

The truth and weight of this doesn’t hit David and Meg until the course has already been set, as if knowing it’s going to happen and watching it happen are the same thing. I won’t detail the scene where the tide turns, as no description could make the point better than when Ketchum promises, “There are some things you know you’ll die before telling, things you know you should have died before ever having seen.”

Both of them, for all their supposed savviness and sensitivity, were wrong about their captors and comrades, imbuing them with a humanity that was never there. At this point, The Girl Next Door leaves The Banality of Evil behind and becomes an entirely different kind of moral document.

After the die of Meg’s death has been cast, David untangles himself from the guilt of complicity enough to see that she and he are both in the hands of “savages … No, not savages … Worse than that … More like a pack of dogs or cats or … swarms of ferocious red ants … Like some other species altogether. Some intelligence that only looked human, but had no access to human feelings … I stood among them swamped by otherness.”

For Meg, bleeding to death in the basement, the only philosophical truth at this new rock bottom beneath the rock bottom of humanity is the knowledge that she’d “been tricked – and now [her] good clear mind was angry with itself … She’d been tricked into thinking Ruth and the others were human in the same way she was human and that consequently it could only go so far … ”

And so it ends, leaving David to grow up differently than he would have if his friends had turned out to be made of the same material that he was.

The fact that they’re not changes the life he’ll inherit, and colors the outlook of Ketchum’s fiction: we share a world with the genuinely inhuman, a strain of being we may never develop the perspective to recognize in time because we share enough evil with it to go a long way down together before parting ways in the dark.

***

David Rice is a writer and animator from Northampton, MA, currently editing his first novel. His stories have appeared in Black Clock, Identity Theory, Spork Press, The Bad Version, NACHT, and The Harvard Advocate. He writes the ongoing web fiction project A Room in Dodge City (aroomindodgecity.com) and the graphic series Lazy Eye Stories (lazyeyestories.com) with artist Kayla Escobedo. He’s online at: www.raviddice.com

Tags: David Rice, Jack Ketchum, The Girl Next Door

To me, what’s uncanny about evil-at-its-most-evil is not that it’s an intimacy with the “genuinely inhuman”, but rather, that it’s not beyond ‘human’. Seeing inhumanity in human action is not seeing darkly enough.

To have the narrator say, in retrospect, that his crush had been “all [he] knew of cruelty” sounds like subtly disclosed delusion.

Ketchum’s novel is a masterpiece, but it has such a (perhaps necessary) abrasiveness that sometimes I think I admire it more than I ‘like’ it. Indeed, it’s not a novel that wants to be liked; it wants to hurt you, to leave you scarred.

Other standout books from Ketchum are Off Season, which is his version of backwoods horror, and The Crossings, a pitch-black Western.